Harry Chapin and Chinese language: Difference between pages

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!--Please used capitalized letters for Standard Mandarin, used as a proper noun here.--> |

|||

{{Infobox Musical artist |

|||

<!--Please refrain from putting (Taiwan) next to the ROC repetitively. It is considered poor form and it is against the Wikipedia policy.--> |

|||

|Name = Harry Chapin |

|||

{{ChineseText}} |

|||

|Img = Harry61880.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox Language |

|||

|Img_capt = Harry Chapin in concert |

|||

|name=Chinese |

|||

|Img_size = 180 |

|||

|nativename={{lang|zh|汉语/漢語}} ''Hànyǔ'', {{lang|zh|中文}} ''Zhōngwén'' |

|||

|Background = solo_singer |

|||

|caption=Zhōngwén in written Chinese |

|||

|Birth_name = |

|||

"Chinese (written) language" (pinyin: zhōngwén) written in Chinese characters |

|||

|Alias = |

|||

|states=[[People's Republic of China]] (commonly known as "China"), [[Republic of China]] (commonly known as "Taiwan"), [[Singapore]], [[Malaysia]], the [[Philippines]], [[California]], [[Sydney]] and other regions with Chinese communities |

|||

|Born = {{birth date|1942|12|7|mf=y}} in [[Greenwich Village]], [[New York City, New York]], [[United States|U.S.]] |

|||

|region=(majorities): East Asia<br />(minorities): Southeast Asia, and other regions with Chinese communities |

|||

|Died = {{death date and age|1981|7|16|1942|12|7|mf=y}}, [[Jericho]], [[Long Island]], [[New York]] [[United States|U.S.A.]] |

|||

|speakers=approx 1.176 billion<!--including [[Overseas Chinese]]//--> |

|||

|Origin = |

|||

|rank=Chinese, all: 1 |

|||

|Instrument = [[singing|Vocals]], [[guitar]], [[piano]] |

|||

|Genre = [[Folk rock]] |

|||

|Occupation = [[Singer-songwriter]], [[musician]] |

|||

|Years_active = 1971 – 1981 |

|||

|Label = [[Elektra Records]]<br>[[Boardwalk Records]]<br>Sequel Records<br>DCC Compact Classics<br>Chapin Productions |

|||

|Associated_acts = |

|||

|URL = http://www.harrychapinmusic.com/ |

|||

}} |

|||

Mandarin: 1 <br /> |

|||

'''Harry Forster Chapin''' ([[December 7]], [[1942]] – [[July 16]], [[1981]]) was an [[United States|American]] singer, [[songwriter]], and [[humanitarian]] who fought to end world hunger. |

|||

Wu: 12 <br /> |

|||

Cantonese: 18 <br /> |

|||

Min: 22 <br /> |

|||

Hakka: 33 <br /> |

|||

Gan: 42 |

|||

|familycolor=Sino-Tibetan |

|||

|script=[[Chinese character]]s, [[Zhuyin fuhao]] |

|||

|nation= |

|||

{{UNO|United Nations}}<br> |

|||

{{PRC|People's Republic of China}} |

|||

*{{HKG|Hong Kong}} |

|||

*{{MAC|Macau}} |

|||

{{ROC|Taiwan}}<br> |

|||

{{SGP|Singapore}}<br><br> |

|||

Recognized as a regional language in<br> |

|||

{{flag|Malaysia}}<br>{{flag|Mauritius}}<br>{{flag|Canada}}<br><small>(Official status in the city of [[Vancouver]], [[British Columbia]])</small> |

|||

|agency=In the PRC: [[National Language Regulating Committee]]<!--[[:zh:国家语言文字工作委员会]]--><ref>http://www.china-language.gov.cn/ (Chinese)</ref><br />In the ROC: [[National Languages Committee]]<br />In Singapore: [[Promote Mandarin Council]]/[[Speak Mandarin Campaign]]<ref>http://mandarin.org.sg/html/home.htm {{Dead link|date=May 2008}}</ref> |

|||

|iso1=zh |

|||

|iso2b=chi |

|||

|iso2t=zho |

|||

|lc1=zho|ld1=Chinese (generic)|ll1=ISO 639 macrolanguage#zho |

|||

|lc2=cdo|ld2=Min Dong|ll2=Min Dong |

|||

|lc3=cjy|ld3=Jinyu|ll3=Jin Chinese |

|||

|lc4=cmn|ld4=Mandarin|ll4=Mandarin Chinese |

|||

|lc5=cpx|ld5=Pu Xian|ll5=Pu Xian |

|||

|lc6=czh|ld6=Huizhou|ll6=Huizhou Chinese |

|||

|lc7=czo|ld7=Min Zhong|ll7=Min Zhong |

|||

|lc8=gan|ld8=Gan|ll8=Gan Chinese |

|||

|lc9=hak|ld9=Hakka|ll9=Hakka Chinese |

|||

|lc10=hsn|ld10=Xiang|ll10=Xiang Chinese |

|||

|lc11=mnp|ld11=Min Bei|ll11=Min Bei |

|||

|lc12=nan|ld12=Min Nan|ll12=Min Nan |

|||

|lc13=wuu|ld13=Wu|ll13=Wu Chinese |

|||

|lc14=yue|ld14=Cantonese|ll14=Cantonese |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Chinese''' or the '''Sinitic language(s)''' (汉语/漢語, [[pinyin]]: ''Hànyǔ''; 华语/華語, ''Huáyǔ''; or 中文, ''Zhōngwén'') can be considered a [[language]] or [[language family]].<ref>*David Crystal, ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987) , p. 312. “The mutual unintelligibility of the varieties is the main ground for referring to them as separate languages.” |

|||

*Charles N. Li, Sandra A. Thompson. ''Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar'' (1989), p 2. “The Chinese language family is genetically classified as an independent branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family.” |

|||

*Jerry Norman. ''Chinese'' (1988), p.1. “The modern Chinese dialects are really more like a family of language. |

|||

*John DeFrancis. ''The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy'' (1984), p.56. "To call Chinese a single language composed of dialects with varying degrees of difference is to mislead by minimizing disparities that according to Chao are as great as those between English and Dutch. To call Chinese a family of languages is to suggest extralinguistic differences that in fact do not exist and to overlook the unique linguistic situation that exists in China." </ref> Originally the indigenous languages spoken by the [[Han Chinese]] in [[China]], it forms one of the two branches of [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan family]] of languages. About one-fifth of the world’s population, or over one [[1,000,000,000 (number)|billion]] people, speak some form of Chinese as their native language. The [[identification of the varieties of Chinese]] as "languages" or "dialects" is controversial.<ref name=Mair>{{cite journal|url=http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp029_chinese_dialect.pdf|journal=Sino-Platonic Papers|last=Mair|first=Victor H.|authorlink=Victor H. Mair|title=What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic Terms|date=1991}}</ref> |

|||

[[Spoken Chinese]] is distinguished by its high level of internal diversity, though all spoken varieties of Chinese are [[tone (linguistics)|tonal]] and [[Analytic language|analytic]]. There are between six and twelve main regional groups of Chinese (depending on classification scheme), of which the most populous (by far) is [[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]] (c. 850 million), followed by [[Wu Chinese|Wu]] (c. 90 million), [[Min Chinese|Min]] (c. 70 million) and [[Cantonese]] (c. 70 million). Most of these groups are [[Mutual intelligibility|mutually unintelligible]], though some, like [[Xiang Chinese|Xiang]] and the Southwest Mandarin dialects, may share common terms and some degree of intelligibility. Chinese is classified as a [[macrolanguage]] with 13 sub-languages in [[ISO 639-3]], though the [[identification of the varieties of Chinese]] as multiple "[[language]]s" or as "[[dialect]]s" of a single language is a contentious issue. |

|||

== Early life and education == |

|||

Chapin was born in [[Brooklyn, New York]], the second of four children born to Jeanne Elspeth ([[married and maiden names|née]] Burke) and [[Jim Chapin]]. His parents divorced by 1950, with Elspeth keeping custody of their four sons, as Jim spent much of his life on the road as a drummer for Big Band era acts such as [[Woody Herman]]. She married ''National Films in Review'' magazine editor Henry Hart a few years later. |

|||

The standardized form of spoken Chinese is [[Standard Mandarin]] ''(Putonghua / Guoyu / Huayu)'', based on the [[Beijing dialect]], which is part of a larger group of North-Eastern and South-Western dialects, often taken as a separate language, see [[Mandarin Chinese]] for more, this language can be referred to as 官话 ''Guānhuà'' or 北方话 ''Běifānghuà'' in Chinese. Standard Mandarin is the official language of the [[People's Republic of China]] and the [[Republic of China]] (commonly known as '[[Taiwan]]'), as well as one of four official languages of [[Singapore]]. Chinese—''de facto'', Standard Mandarin—is one of the six official languages of the [[United Nations]]. Of the other varieties, [[Standard Cantonese]] is common and influential in Cantonese-speaking overseas communities, and remains one of the official languages of [[Hong Kong]] (together with [[English language|English]]) and of [[Macau]] (together with [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]]). [[Min Nan]], part of the Min language group, is widely spoken in southern [[Fujian]], in neighbouring [[Taiwan]] (where it is known as [[Taiwanese]] or Hoklo) and in [[Southeast Asia]] (where it dominates in [[Singapore]] and [[Malaysia]] and is known as Hokkien). |

|||

Chapin's first formal introduction to music was while singing in the [[Brooklyn Boys Choir]]. It was here that Harry met [[John Wallace|Big John Wallace]], a tenor with a five-octave range, who would later become his bass player and background singer. He began performing with his brothers while a teenager, with their father occasionally joining them on drums. |

|||

According to news reports in March 2007, 86 percent of people in the People's Republic of China speak a variant of [[spoken Chinese]].<ref>[http://big5.xinhuanet.com/gate/big5/news.xinhuanet.com/edu/2004-12/27/content_2383853.htm 全國約有53%的人能用普通話交流<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> As a language family, the number of Chinese speakers is 1.136 billion. The same news report indicate 53 percent of the population, or 700 million speakers, can effectively communicate in Putonghua. |

|||

Chapin graduated from [[Brooklyn Technical High School]] in 1960, and was among the five inductees in the school's Alumni Hall Of Fame for the year 2000. He briefly attended the [[United States Air Force Academy]] and was then an intermittent student at [[Cornell University]]. He did not complete a degree. |

|||

== Spoken Chinese == |

|||

He originally intended to be a [[documentary film|documentary film-maker]], and directed ''[[Legendary Champions]]'' in 1968, which was nominated for a documentary [[Academy Awards|Academy Award]]. In 1971, he decided to focus on music. With [[John Wallace (musician)|Big John Wallace]], [[Tim Scott (musician)|Tim Scott]] and [[Ron Palmer]], Chapin started playing in various local [[nightclub]]s in [[New York City]]. |

|||

{{main|Spoken Chinese}} |

|||

Harry Chapin is raw |

|||

<!--This is a summary. Please add new information to [[Chinese spoken language]].--> |

|||

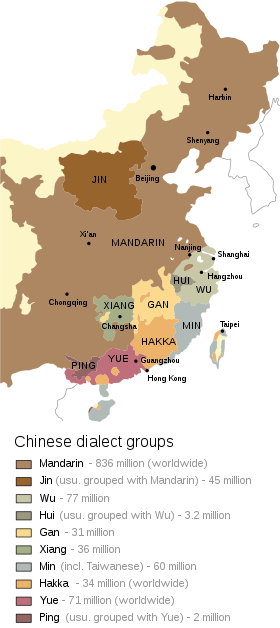

The map below depicts the linguistic subdivisions ("languages" or "dialect groups") within China itself. The traditionally-recognized seven main groups, in order of population size are: |

|||

== Recording career == |

|||

*[[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]] 北方话/北方話 or 官話/官话, (c. 850 million), |

|||

Following an unsuccessful early album made with his brothers, [[Tom Chapin|Tom]] and [[Steve Chapin|Steve]], Chapin's debut album was ''[[Heads and Tales]]'' (1972, #60), which was a success thanks to the single "[[Taxi (song)|Taxi]]" (#24). Chapin later gave great credit to [[WWZN|WMEX]]-Boston radio personality [[Jim Connors]] for being the DJ who "discovered" this single, and pushed the air play of this song amongst fellow radio programmers in the U.S.{{fact|date=July 2008}} |

|||

*[[Wu Chinese|Wu]] 吳/吴 , which includes [[Shanghainese]], (c. 90 million), |

|||

*[[Cantonese]] (Yue) 粵/粤, (c. 80 million), |

|||

*[[Min Chinese|Min]] 閩/闽, which includes [[Taiwanese]], (c. 50 million), |

|||

*[[Xiang Chinese|Xiang]] 湘, (c. 35 million), |

|||

*[[Hakka Chinese|Hakka]] 客家 or 客, (c. 35 million), |

|||

*[[Gan Chinese|Gan]] 贛/赣, (c. 20 million) |

|||

Chinese linguists have recently distinguished: |

|||

However, Chapin's recording future became somewhat of a controversy between two powerful record companies headed by two very powerful men, [[Jac Holzman]] of [[Elektra Records]] and [[Clive Davis]] of [[Columbia Records|Columbia]]. According to Chapin's biography ''Taxi: The Harry Chapin Story'' by [[Peter M. Coan]], Chapin had agreed in principle to sign with Elektra Records on the grounds that a smaller record label would give greater personal attention to his work. Clive Davis, however, remained undaunted, doubling almost every cash advance offer Chapin received from Holzman. Despite a cordial relationship with Holzman, Davis had a long history of besting Holzman over the years to particular artists, but this was one time that he did not prevail. |

|||

*[[Jin Chinese|Jin]] 晉/晋 from Mandarin |

|||

*[[Huizhou Chinese|Huizhou]] 徽 from Wu |

|||

*[[Pinghua Chinese|Ping]] 平話/平话 partly from Cantonese |

|||

There are also many smaller groups that are not yet classified, such as: [[Danzhou dialect]], spoken in [[Danzhou]], on [[Hainan]] Island; [[Xianghua]] (乡话), not to be confused with Xiang (湘), spoken in western [[Hunan]]; and [[Shaozhou Tuhua]], spoken in northern [[Guangdong]]. The [[Dungan language]], spoken in [[Central Asia]], is very closely related to Mandarin. However, it is not generally considered "Chinese" since it is written in [[Cyrillic]] and spoken by [[Dungan people]] outside [[China]] who are not considered ethnic [[Overseas Chinese|Chinese]]. See [[List of Chinese dialects]] for a comprehensive listing of individual dialects within these large, broad groupings. |

|||

Chapin ultimately signed with Elektra for a smaller advance, but with provisions that made it worth the move. The biggest stipulation in the nine-album deal was that he receive free studio time, meaning he paid no recording costs. It was a move that would ultimately save Chapin hundreds of thousands of dollars over the term of his contract and set a precedent for other musicians. |

|||

In general, the above language-dialect groups do not have sharp boundaries, though Mandarin is the pre-dominant Sinitic language in the North and the Southwest, and the rest are mostly spoken in Central or Southeastern China. Frequently, as in the case of the [[Guangdong]] province, native speakers of major variants overlapped. As with many areas that were linguistically diverse for a long time, it is not always clear how the speeches of various parts of China should be classified. The [[Ethnologue]] lists a total of [http://www.ethnologue.com/show_family.asp?subid=90151 14], but the number varies between seven and seventeen depending on the classification scheme followed. For instance, the Min variety is often divided into Northern Min (Minbei, Fuchow) and Southern Min (Minnan, Amoy-Swatow); linguists have not determined whether their mutual intelligibility is large enough to sort them as separate languages. |

|||

"This was completely unheard of," said Davis in the Coan book. "There was no such thing as free studio time." |

|||

[[Image:Map of sinitic languages-en.svg|thumb|280px|The varieties of spoken Chinese in [[China]] and [[Taiwan]]]] |

|||

In general, mountainous South China displays more linguistic diversity than the flat North China. In parts of South China, a major city's dialect may only be marginally intelligible to close neighbours. For instance, [[Wuzhou]] is about 120 miles upstream from [[Guangzhou]], but its dialect is more like [[Standard Cantonese]] spoken in Guangzhou, than is that of [[Taishan]], 60 miles southwest of Guangzhou and separated by several rivers from it (Ramsey, 1987). |

|||

Chapin's follow-up album, ''[[Sniper and Other Love Songs]]'' (1972, #160), was less successful despite containing the Chapin anthem "Circle" (a big European hit for [[The New Seekers]]). His third album, ''[[Short Stories (Harry Chapin album)|Short Stories]]'' (1974, #61), was a major success. ''[[Verities & Balderdash]]'' (1974, #4), released soon after, was even more successful, bolstered by the chart-topping hit single "[[Cat's in the Cradle]]", based upon a poem by his wife. Sandy Chapin had written the poem inspired by her first husband's relationship with his father and a country song she heard on the radio.<ref>[http://www.harrychapin.com/circle/winter04/behind.htm "Mike Grayeb, Behind The Song: Cat's In The Cradle" ] Circle!</ref> When Harry's son Josh was born, he got the idea to put music to the words and recorded the result. "Cat's in the Cradle" was Chapin's only number one hit, shooting album sales skyward and making him a millionaire. |

|||

====Standard Mandarin and diglossia==== |

|||

He also wrote and performed a [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] [[musical theatre|musical]] ''[[The Night That Made America Famous]]''. Additionally, Chapin wrote the music and lyrics for ''[[Cotton Patch Gospel]]'', a musical by Tom Key based on [[Clarence Jordan]]'s book ''The Cotton Patch Version of Matthew and John''. The original cast soundtrack was produced by Tom Chapin, and released in 1982 by Chapin Productions. |

|||

{{main|Standard Mandarin}} |

|||

<!--This is a SUMMARY. Please add new information to [[Standard Mandarin]].--> |

|||

[[Standard Mandarin|Putonghua / Guoyu]], often called "Mandarin", is the official [[standard language]] used by the [[People's Republic of China]], the [[Republic of China]], and [[Singapore]] (where it is called "Huayu"). It is based on the [[Beijing dialect]], which is the dialect of [[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]] as spoken in [[Beijing]]. The governments intend for speakers of all Chinese speech varieties to use it as a common language of communication. Therefore it is used in government agencies, in the media, and as a language of instruction in schools. |

|||

In both [[mainland China]] and [[Taiwan]], [[diglossia]] has been a common feature: it is common for a Chinese to be able to speak two or even three varieties of the Sinitic languages (or “dialects”) together with Standard Mandarin. For example, in addition to ''putonghua'' a resident of [[Shanghai]] might speak [[Shanghainese]] and, if they did not grow up there, his or her local dialect as well. A native of [[Guangzhou]] may speak Standard Cantonese and ''putonghua'', a resident of Taiwan, both [[Taiwanese]] and ''putonghua/guoyu''. A person living in [[Taiwan]] may commonly mix pronunciations, phrases, and words from [[Standard Mandarin]] and [[Taiwanese]], and this mixture is considered socially appropriate under many circumstances. In Hong Kong, standard Mandarin is beginning to take its place beside English and Standard Cantonese, the official languages. |

|||

Chapin's only UK hit was "[[W*O*L*D]]", which reached #34 in 1974. His popularity in the UK owed much to the championing of [[BBC]] disc jockey [[Noel Edmonds]]. The song's success in the U.S. was championed by [[WWZN|WMEX]] jock and friend of Chapin's [[Jim Connors]] whom the basis of the song was inspired by..{{fact|date=July 2008}} The national appeal of the song was a result of disc jockeys playing it for themselves, since the song dealt with a much-traveled DJ, problems in his personal life, and his difficulty with ageing in the industry. This song was also a significant inspiration (though not the only one) for Hugh Wilson, who created the popular television series about DJs and radio, ''[[WKRP in Cincinnati]]''.{{fact|date=August 2008}} |

|||

===Linguistics=== |

|||

Chapin's recording of "The Shortest Story", a song he wrote about a dying child and featured in his 1976 live/studio album ''[[Greatest Stories Live]]'', was named by author Tom Reynolds in his book ''[[I Hate Myself And Want To Die|I Hate Myself and Want to Die]]'' as the second most depressing song of all time (just behind "[[The Christmas Shoes]]"). |

|||

{{main|Identification of the varieties of Chinese}} |

|||

<!--This is a SUMMARY. Please add new information to [[Identification of the varieties of Chinese]]. Please do not change info here w/o discussion as it is deemed fairly objective--> |

|||

Linguists often view Chinese as a [[language family]], though owing to China's socio-political and cultural situation, and the fact that all spoken varieties use one common written system, it is customary to refer to these generally mutually unintelligible variants as “the Chinese language”. The diversity of Sinitic variants is comparable to the [[Romance languages]]. |

|||

From a purely [[Linguistic prescription|descriptive]] point of view, "languages" and "dialects" are simply arbitrary groups of similar idiolects, and the distinction is irrelevant to linguists who are only concerned with describing regional speeches technically. However, the idea of a single language has major overtones in politics and cultural self-identity, and explains the amount of emotion over this issue. Most Chinese and Chinese linguists refer to Chinese as a single language and its subdivisions dialects, while others call Chinese a language family. |

|||

By the end of the decade, Chapin's contract with Elektra (which had since merged with Asylum Records under the control of [[David Geffen]]) had expired, and the company made no offer to renew it. A minor deal with Casablanca fell through, and Chapin settled on a simple one-album deal with Boardwalk Records. The Boardwalk album, though no one knew it at the time, would be his final work. |

|||

Chinese itself has a term for its unified writing system, ''Zhongwen'' (中文), while the closest equivalent used to describe its spoken variants would be ''Hanyu'' (汉语,“spoken language[s] of the [[Han Chinese]]) – this term could be translated to either “language” or “languages” since Chinese possesses no [[grammatical number]]s. In the Chinese language, there is much less need for a uniform speech-and-writing continuum, as indicated by two separate character morphemes 语 ''yu'' and 文 ''wen''. Ethnic Chinese often consider these spoken variations as one single language for reasons of [[nationality]] and as they inherit one common cultural and linguistic heritage in [[Classical Chinese]]. Han native speakers of Wu, Min, Hakka, and Cantonese, for instance, may consider their own linguistic varieties as separate spoken languages, but the [[Han Chinese]] race as one – albeit internally very diverse – ethnicity. To Chinese nationalists, the idea of Chinese as a language family may suggest that the Chinese identity is much more fragmentary and disunified than it actually is and as such is often looked upon as culturally and politically provocative. Additionally, in [[Taiwan]], it is closely associated with Taiwanese independence, where some supporters of [[Taiwanese independence]] promote the local Taiwanese [[Minnan]]-based spoken language. |

|||

The title track of his last album, ''[[Sequel (album)|Sequel]]'', was a follow up to his earlier song "Taxi", reuniting the same characters ten years later. The songs Chapin was working on at the time of his death were subsequently released as the thematic album ''[[The Last Protest Singer]]''. |

|||

Within the People’s Republic of China and Singapore, it is common for the government to refer to all divisions of the Sinitic language(s) beside standard Mandarin as ''fangyan'' (“regional tongues”, often translated as “[[dialect]]s”). Modern-day Chinese speakers of all kinds communicate using [[Vernacular Chinese|one formal standard written language]], although this modern written standard is modeled after Mandarin, generally the modern Beijing substandard. |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

Chapin met Sandy Gaston, a New York socialite nine years his senior, in 1966, after she called him asking for music lessons. They married two years later. The story of their meeting and romance is told in his song "[[I Wanna Learn a Love Song]]". He fathered two children with her, [[Jen Chapin|Jennifer]] and Joshua, and was stepfather to her three children by a previous marriage. |

|||

===Language and nationality=== |

|||

==Philanthropic work== |

|||

The term '''sinophone''', coined in analogy to [[anglophone]] and [[francophone]], refers to those who speak the Chinese language natively, or prefer it as a medium of communication. The term is derived from [[Sinae]], the Latin word for ancient China. |

|||

Chapin was resolved to leave his imprint on Long Island. He envisioned a Long Island where the arts flourished and universities expanded and humane discourse was the norm. "He thought Long Island represented a remarkable opportunity," said Chapin's widow, Sandy.<ref>{{cite journal |title=More than a Troubadour |journal=Newsday |url=http://www.newsday.com/community/guide/lihistory/ny-history-hs9chap,0,6013734.story |accessdate=2008-01-18 |first=Fred |last=Bruning}}</ref> |

|||

===Written Chinese=== |

|||

Chapin served on the boards of the Eglevsky Ballet, the Long Island Philharmonic, Hofstra University. He energized the now-defunct Performing Arts Foundation (PAF) of Huntington. |

|||

{{main|Chinese written language}} |

|||

:''See also'': ''[[Classical Chinese]]'' and ''[[Vernacular Chinese]]'' |

|||

<!--This is a SUMMARY. Please add new information to [[Chinese written language]].--> |

|||

The relationship among the Chinese spoken and written languages is a complex one. Its spoken variations evolved at different rates, while written Chinese itself has changed much less. [[Classical Chinese]] [[literature]] began in the [[Spring and Autumn period]], although written records have been discovered as far back as the 14th to 11th centuries BCE [[Shang dynasty]] [[oracle bone]]s using the [[oracle bone script]]s. |

|||

In the mid-1970s, Chapin focused on his social activism, including raising money to combat hunger in the United States. His daughter Jen said: "He saw hunger and poverty as an insult to America"<ref name=jeninterview>"[http://www.boston.com/ae/music/articles/2004/02/20/jen_chapin_shares_her_dads_idealism____but_not_his_voice/ Jen Chapin shares her dad's idealism - but not his voice]", Boston Globe, [[February 20]], [[2004]]</ref>. He co-founded the organization [[World Hunger Year]] with legendary radio DJ [[Bill Ayres]], before returning to music with ''[[On the Road to Kingdom Come]]''. He also released a book of poetry, ''[[Looking...Seeing]]'', in 1977. Many of Chapin's concerts were benefit performances (for example, a concert<ref>http://cinematreasures.org/theater/54/ Text of 1977 review of Chapin concert at Landmark Thetre</ref> to help save the [[Landmark Theatre (Syracuse, New York)|Landmark Theatre]] in [[Syracuse, New York]]), and sales of his concert merchandise were used to support [[World Hunger Year]]. |

|||

The Chinese [[orthography]] centers around Chinese characters, ''hanzi'', which are written within imaginary rectangular blocks, traditionally arranged in vertical columns, read from top to bottom down a column, and right to left across columns. Chinese characters are [[morpheme]]s independent of phonetic change. Thus the number "one", ''yi'' in [[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]], ''yat'' in [[Cantonese]] and ''chi̍t'' in [[Hokkien dialect|Hokkien]] (form of Min), all share an identical character ("一"). Vocabularies from different major Chinese variants have diverged, and colloquial non-standard written Chinese often makes use of unique "dialectal characters", such as 冇 and 係 for [[Cantonese]] and [[Hakka]], which are considered archaic or unused in standard written Chinese. |

|||

Chapin's social causes at times caused friction among his band members and manager [[Fred Kewley]]. Chapin donated an estimated third of his paid concerts to charitable causes, often performing alone with his guitar to reduce costs. |

|||

Written colloquial Cantonese has become quite popular in online [[chat room]]s and [[instant messaging]] amongst Hong-Kongers and Cantonese-speakers elsewhere. Use of it is considered highly informal, and does not extend to any formal occasion. |

|||

One report quotes his widow saying soon after his death - "only with slight exaggeration" - that "Harry was supporting 17 relatives, 14 associations, seven foundations and 82 charities. Harry wasn't interested in saving money. He always said, 'Money is for people,' so he gave it away." Despite his success as a musician, he left little money and it was difficult to maintain the causes for which he raised more than $3 million in the last six years of his life <ref>"Harry Chapin's Family Fights to Carry On His Extraordinary Legacy of Compassion", Gioia Diliberto, ''People'', March 15, 1982</ref>. The [[Harry Chapin Foundation]] was the result. |

|||

Also, in [[Hunan]], some women write their local language in [[Nü Shu]], a [[syllabary]] derived from [[Chinese character]]s. The [[Dungan language]], considered by some a dialect of Mandarin, is also nowadays written in [[Cyrillic]], and was formerly written in the [[Arabic alphabet]], although the [[Dungan]] people live outside [[China]]. |

|||

== Death == |

|||

[[Image:Harrychapingravesite.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Harry Chapin's Gravesite]] |

|||

On Thursday, [[July 16]], [[1981]], just after noon, Chapin was driving on the [[Long Island Expressway]], in the left hand fast lane, at about {{convert|105|km|mi}} an hour on the way to his concert. For some reason, either because of engine failure or some physical problem (thought to be a possible [[heart attack]]) he put on his emergency flashers near Exit 40 in [[Jericho, NY]]. He then slowed to about {{convert|24|km|mi}} an hour and veered into the centre lane, nearly colliding with another car. He swerved left, then to the right again, ending up directly in front of a [[tractor-trailer truck]]. The truck could not brake in time and rammed the rear of Harry's blue 1975 [[Volkswagen Rabbit]], rupturing the gas tank and causing it to burst into flames. |

|||

===Chinese characters=== |

|||

The driver of the truck and a passerby were able to get Harry out of the burning car through the window and by cutting the seat belts before the car was completely engulfed in flames. He was taken by police helicopter to the hospital where ten doctors tried for 30 minutes to revive him. A spokesman for the Nassau County Medical Center said Chapin had suffered a heart attack and "died of cardiac arrest" but there was no way of knowing whether it occurred before or after the accident. In an interview years after his death, Chapin's daughter said "My dad didn't really sleep, and he ate badly and had a totally insane schedule."<ref name=jeninterview/> |

|||

{{main|Chinese character}} |

|||

<!--This is a SUMMARY. Please add new information to [[Chinese character]].--> |

|||

Chinese characters evolved over time from earliest forms of [[hieroglyph]]s. The idea that all Chinese characters are either [[pictograph]]s or [[ideograph]]s is an erroneous one: most characters contain phonetic parts, and are composites of phonetic components and semantic [[Radical (Chinese character)|Radical]]s. Only the simplest characters, such as ''ren'' 人 (human), ''ri'' 日 (sun), ''shan'' 山 (mountain), ''shui'' 水 (water), may be wholly pictorial in origin. In 100 CE, the famed scholar [[Xu Shen|''Xǚ Shèn'']] in the [[Han Dynasty|Hàn Dynasty]] classified characters into 6 categories, namely pictographs, simple ideographs, compound ideographs, phonetic loans, phonetic compounds and derivative characters. Of these, only 4% were categorized as pictographs, and 80-90% as phonetic complexes consisting of a ''semantic'' element that indicates meaning, and a ''phonetic'' element that arguably once indicated the pronunciation. There are about 214 radicals recognized in the [[Kangxi Dictionary]], which indicate what the character is about semantically. |

|||

Even though Chapin was driving without a license, his driver's license having previously been revoked for a long string of traffic violations, his widow Sandy won a $12 million decision in a negligence lawsuit against the owners of the truck. |

|||

Modern characters are styled after the [[kaishu|standard script]] (楷书/楷書 ''kǎishū'') (see styles, below). Various other written styles are also used in [[East Asian calligraphy]], including seal script (篆书/篆書 zhuànshū), cursive script (草书/草書 cǎoshū) and clerical script (隶书/隸書 lìshū). Calligraphy artists can write in traditional and simplified characters, but tend to use traditional characters for traditional art. |

|||

[[Image:shodo.jpg|thumb|250px|Various styles of Chinese calligraphy.]] |

|||

There are currently two systems for Chinese characters. The [[Traditional Chinese character|traditional system]], still used in [[Hong Kong]], [[Taiwan]], [[Macau]] and Chinese speaking communities (except [[Singapore]] and [[Malaysia]]) outside [[mainland China]], takes its form from standardized character forms dating back to the late [[Han dynasty]]. The [[Simplified Chinese character]] system, developed by the People's Republic of China in 1954 to promote mass [[literacy]], simplifies most complex traditional [[glyph]]s to fewer strokes, many to common ''[[caoshu]]'' [[shorthand]] variants. |

|||

Chapin was interred in the Huntington Rural Cemetery, [[Huntington, New York]]. His epitaph is taken from his song ''"I Wonder What Would Happen to this World."'' It is: |

|||

: |

|||

:''Oh if a man tried'' |

|||

:''To take his time on Earth'' |

|||

:''And prove before he died'' |

|||

:''What one man's life could be worth'' |

|||

:''I wonder what would happen '' |

|||

:''to this world'' |

|||

[[Singapore]], which has two large Chinese communities, is the first – and at present the only – foreign nation to officially adopt simplified characters, although it has also become the ''de facto'' standard for younger ethnic Chinese in [[Malaysia]]. The [[Internet]] provides the platform to practice reading the alternative system, be it traditional or simplified. |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||

A well-educated Chinese today recognizes approximately 6,000-7,000 characters; some 3,000 characters are required to read a Mainland [[newspaper]]. The PRC government defines literacy amongst workers as a knowledge of 2,000 characters, though this would be only functional literacy. A large unabridged [[dictionary]], like the [[Kangxi Dictionary]], contains over 40,000 characters, including obscure, variant and archaic characters; less than a quarter of these characters are now commonly used.'' |

|||

On [[December 7]], [[1987]], Harry Chapin was posthumously awarded the [[Congressional Gold Medal]] for his campaigning on social issues, particularly his highlighting of hunger around the world and in the United States. His work on hunger included being widely recognized as a key player in the creation of the Presidential Commission on World Hunger in 1977. |

|||

==History and evolution== |

|||

A [[biography]] of Chapin entitled ''Taxi: The Harry Chapin Story'', by Peter M. Coan, was released following his death. Although Chapin had cooperated with the writer, following his death the family withdrew their support. There is some debate about the accuracy of the details included in the book. |

|||

Most linguists classify all varieties of modern spoken Chinese as part of the Sino-Tibetan [[language family]] and believe that there was an original language, termed [[Proto-Sino-Tibetan]], from which the Sinitic and Tibeto-Burman languages descended. The relation between Chinese and other Sino-Tibetan languages is an area of active research, as is the attempt to reconstruct Proto-Sino-Tibetan. The main difficulty in this effort is that, while there is enough documentation to allow one to reconstruct the ancient Chinese sounds, there is no written documentation that records the division between proto-Sino-Tibetan and ancient Chinese. In addition, many of the older languages that would allow us to reconstruct Proto-Sino-Tibetan are very poorly understood and many of the techniques developed for analysis of the descent of the Indo-European languages from [[Proto-Indo-European language|PIE]] don't apply to Chinese because of "morphological paucity" especially after Old Chinese <ref>[http://languageserver.uni-graz.at/ls/mat?id=1181&type=m Analysis of the concept "wave" in PST.]</ref>. |

|||

Categorization of the development of Chinese is a subject of scholarly debate. One of the first systems was devised by the [[Sweden|Swedish]] linguist [[Bernhard Karlgren]] in the early 1900s; most present systems rely heavily on Karlgren's insights and methods. |

|||

Despite seeming social and political differences with Chapin, [[Dr. James Dobson]] often quotes the entirety of "Cat's In The Cradle" to illustrate dynamics of contemporary American families. "Cat's In The Cradle" was also re-recorded by [[hard rock]] group [[Ugly Kid Joe]] in 1992 and once again topped the charts. A country version was also recorded by [[Ricky Skaggs]] in 1995. It was sampled by Canadian singer [[Sarah McLachlan]], and subsequently by [[Darryl McDaniels]] of [[Run DMC]] in 2006 after the rapper's discovery that he was adopted in infancy. [[Jason Downs]] also recorded an "updated" version of the song entitled "Revenue". |

|||

[[Old Chinese]] ({{zh-tsps|t=上古漢語|s=上古汉语|p=Shànggǔ Hànyǔ}}), sometimes known as "Archaic Chinese", was the language common during the early and middle [[Zhou Dynasty (1122 BCE - 256 BCE)|Zhōu Dynasty]] (1122 BCE - 256 BCE), texts of which include inscriptions on bronze artifacts, the poetry of the ''[[Shijing|Shījīng]],'' the history of the ''[[Shujing|Shūjīng]],'' and portions of the ''[[Yijing|Yìjīng]]'' (''I Ching''). The phonetic elements found in the majority of Chinese characters provide hints to their Old Chinese pronunciations. The pronunciation of the borrowed Chinese characters in Japanese, Vietnamese and Korean also provide valuable insights. Old Chinese was not wholly uninflected. It possessed a rich sound system in which [[aspiration]] or rough breathing differentiated the consonants, but probably was still without tones. Work on reconstructing Old Chinese started with [[Qing dynasty|Qīng dynasty]] [[philologist]]s. |

|||

His song "Cat's in the Cradle" was used in an episode of ''[[The Simpsons]]'' and in an episode of ''[[Family Guy]]'', and was featured in ''[[Shrek The Third]]''. The song has also been heard many other times on television and film. |

|||

Some early [[Indo-European]] loanwords in Chinese have been proposed, notably [[:wikt:蜜|蜜]] ''mì'' "honey", [[:wikt:獅|獅]] ''shī'' "lion," and perhaps also [[:wikt:馬|馬]] ''mǎ'' "horse", [[:wikt:犬|犬]] ''quǎn'' "dog", and [[:wikt:鵝|鵝]] ''é'' "goose".<ref> [[Encyclopedia Britannica]] s.v. "Chinese languages": "Old Chinese vocabulary already contained many words not generally occurring in the other Sino-Tibetan languages. The words for ‘honey' and ‘lion,' and probably also ‘horse,' ‘dog,' and ‘goose,' are connected with Indo-European and were acquired through trade and early contacts. (The nearest known Indo-European languages were Tocharian and Sogdian, a middle Iranian language.) A number of words have Austroasiatic cognates and point to early contacts with the ancestral language of Muong-Vietnamese and Mon-Khmer" [http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-75039/Chinese-languages]; Jan Ulenbrook, ''Einige Übereinstimmungen zwischen dem Chinesischen und dem Indogermanischen'' (1967) proposes 57 items; see also Tsung-tung Chang, 1988 [http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp007_old_chinese.pdf Indo-European Vocabulary in Old Chinese];.</ref> |

|||

[[Middle Chinese]] ({{zh-tsps|s=中古汉语|t=中古漢語|p=Zhōnggǔ Hànyǔ}}) was the language used during the [[Sui dynasty|Suí]], [[Tang dynasty|Táng]], and [[Song dynasty|Sòng]] dynasties (6th through 10th centuries CE). It can be divided into an early period, reflected by the 切韻 "[[Qieyun|Qièyùn]]" [[rime book|rhyme table]] (601 CE), and a late period in the 10th century, reflected by the 廣韻 "[[Guangyun|Guǎngyùn]]" [[rime book|rhyme table]]. Linguists are more confident of having reconstructed how Middle Chinese sounded. The evidence for the pronunciation of Middle Chinese comes from several sources: modern dialect variations, rhyming dictionaries, foreign transliterations, "rhyming tables" constructed by ancient Chinese philologists to summarize the phonetic system, and Chinese phonetic translations of foreign words. However, all reconstructions are tentative; some scholars have argued that trying to reconstruct, say, modern Cantonese from modern [[Cantopop]] rhymes would give a fairly inaccurate picture of the present-day spoken language. |

|||

His song "Cat's in the Cradle" ranked number 186 of 365 on the [[RIAA]] list of [[Songs of the Century]]. |

|||

The development of the spoken Chinese languages from early historical times to the present has been complex. Most Chinese people, in [[Sichuan|Sìchuān]] and in a broad arc from the northeast ([[Manchuria]]) to the southwest ([[Yunnan]]), use various Mandarin dialects as their [[home language]]. The prevalence of Mandarin throughout northern China is largely due to north China's plains. By contrast, the mountains and rivers of middle and southern China promoted linguistic diversity. |

|||

Harry Chapin was inducted into the [[Long Island Music Hall of Fame]] on [[October 15]] [[2006]]. |

|||

Until the mid-20th century, most southern Chinese only spoke their native local variety of Chinese. As Nanjing was the [[capital]] during the early [[Ming dynasty]], Nanjing Mandarin became dominant at least until the later years of the officially [[Manchu]]-speaking [[Qing Empire]]. Since the 17th century, the Empire had set up [[orthoepy]] academies ({{zh-tsps|t=正音書院|s=正音书院|p=Zhèngyīn Shūyuàn}}) to make pronunciation conform to the Qing capital Beijing's standard, but had little success. During the Qing's last 50 years in the late 19th century, the Beijing Mandarin finally replaced Nanjing Mandarin in the imperial court. For the general population, though, a single standard of Mandarin did not exist. The non-Mandarin speakers in southern China also continued to use their various languages for every aspect of life. The new Beijing Mandarin court standard was used solely by officials and civil servants and was thus fairly limited. |

|||

The rock band M.O.D. wrote an irreverent song about Harry Chapin's death called "Ode To Harry". [[Hector (musician)|Hector]] released a [[Finland|Finnish-language]] cover version of his song "Six String Orchestra". The cover can be heard under the name "Monofilharmoonikko" as the sixth track of the 1977 album ''H.E.C.''; it was released as a single as well. |

|||

This situation did not change until the mid-20th century with the creation (in both the PRC and the ROC, but not in Hong Kong) of a compulsory educational system committed to teaching [[Standard Mandarin]]. As a result, Mandarin is now spoken by virtually all young and middle-aged citizens of [[mainland China]] and on [[Taiwan]]. [[Standard Cantonese]], not Mandarin, was used in [[Hong Kong]] during its the time of its British colonial period (owing to its large Cantonese native and migrant populace) and remains today its official language of education, formal speech, and daily life, but Mandarin is becoming increasingly influential after the [[Transfer of the sovereignty of Hong Kong|1997 handover]]. |

|||

A graduate student apartment complex, Harry Chapin Apartments at [[Stony Brook University]] on Long Island, is named after Chapin. |

|||

Chinese was once the [[Lingua franca]] for East Asia countries for centuries, before the rise of European influences in 19th century. |

|||

The Lakeside Theatre at Eisenhower Park in East Meadow,NY was renamed "Harry Chapin Lakeside Theatre" during a memorial concert held one month after his death, as a tribute to his efforts to combat world hunger. |

|||

==Influences on other languages== |

|||

The comedy team [[Smothers Brothers|The Smothers Brothers]] have often performed a version of "Six String Orchestra" when they tour and perform with local symphonies. The song usually takes about 10 to 15 minutes to complete as they stop and banter back and forth. Dick usually stops the song to sarcastically tell Tommy what great guitar playing he did. |

|||

Throughout history [[Chinese culture]] and politics has had a great influence on unrelated languages such as [[Korean language|Korean]] and [[Japanese language|Japanese]]. Korean and Japanese both have writing systems employing [[Chinese character]]s (Hanzi), which are called [[Hanja]] and [[Kanji]], respectively. |

|||

The Vietnamese term for Chinese writing is [[Hán tự]]. It was the only available method for writing Vietnamese until the 14th century, used almost exclusively by Chinese-educated Vietnamese élites. From the 14th to the late 19th century, Vietnamese was written with [[Chữ nôm]], a modified Chinese script incorporating sounds and syllables for native Vietnamese speakers. Chữ nôm was completely replaced by a modified Latin script created by the Jesuit missionary priest Alexander de Rhodes, which incorporates a system of diacritical marks to indicate tones, as well as modified consonants. The Vietnamese language exhibits multiple elements similar to Cantonese in regard to the specific intonations and sharp consonant endings. There is also a slight influence from Mandarin, including the sharper vowels and "kh" (IPA:x) sound missing from other Asiatic languages. |

|||

In the film "One Trick Pony" musician Paul Simon portrays Jonah, an aging rock star famous for a 1960s protest song. In one scene Jonah is approached at an airport by Hare Krishna followers. To their "Hare Krishna?" Jonah responds "Harry Chapin". |

|||

In [[South Korea]], the [[Hangul]] alphabet is generally used, but [[Hanja]] is used as a sort of boldface. In [[North Korea]], [[Hanja]] has been discontinued. Since the modernization of Japan in the late 19th century, there has been debate about abandoning the use of Chinese characters, but the practical benefits of a radically new script have so far not been considered sufficient. |

|||

==Extended family== |

|||

In [[Guangxi]] the [[Zhuang]] also had used derived Chinese characters or [[Zhuang logogram]]s to write songs, even though Zhuang is not a Chinese dialect. Since the 1950s, the [[Zhuang language]] has been written in a modified Latin alphabet.<ref>Zhou, Mingliang: ''Multilingualism in China: The Politics of Writing Reforms for Minority Languages, 1949-2002'' (Walter de Gruyter 2003); ISBN 3-11-017896-6; p. 251–258.</ref> |

|||

Chapin often remarked that he came from an artistic family. His father [[Jim Chapin]] and brothers [[Tom Chapin]] and [[Steve Chapin]] are also musicians, as are his daughter, [[Jen Chapin]], and two of his nieces (see the [[Chapin Sisters]]). His paternal grandfather was an artist who illustrated [[Robert Frost|Robert Frost's]] first two books of poetry; his maternal grandfather was the [[philosopher]] [[Kenneth Burke]]. |

|||

Languages within the influence of Chinese culture also have a very large number of [[loanword]]s from Chinese. Fifty percent or more of Korean vocabulary is of Chinese origin and the influence on Japanese and Vietnamese has been considerable. Ten percent of Philippine language vocabularies are of Chinese origin. Chinese also shares a great many grammatical features with these and neighboring languages, notably the lack of [[grammatical gender|gender]] and the use of [[classifier (linguistics)|classifiers]]. |

|||

Notable musicians in their own right, Tom and Steve Chapin sometimes performed with Harry throughout his career, as is especially evident on the live albums ''[[Greatest Stories Live]]'' and ''[[Legends of the Lost and Found]]''. He also performed with them before his solo career took off, as seen on the album ''[[Chapin Music!]]'' Chapin's family members and other longtime bandmates have continued to perform together from time to time in the decades since his death. |

|||

Loan words from Chinese also exist in European languages such as English. Examples of such words are "tea" from the Minnan pronunciation of 茶 ([[POJ]]: tê), "ketchup" from the Cantonese pronunciation of 茄汁 (ke chap), and "kumquat" from the Cantonese pronunciation of 金橘 (kam kuat). |

|||

== Discography == |

|||

LPs: |

|||

* ''[[Chapin Music!]]'' (1966, Rock-Land Records) |

|||

* ''[[Heads and Tales]]'' (1972, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Sniper and Other Love Songs]]'' (1972, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Short Stories (Harry Chapin album)|Short Stories]]'' (1973, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Verities & Balderdash]]'' (1974, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Portrait Gallery]]'' (1975, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Greatest Stories Live]]'' (Double Album, 1976, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[On the Road to Kingdom Come]]'' (1976, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Dance Band on the Titanic]]'' (Double Album, 1977, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Living Room Suite]]'' (1978, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Legends of the Lost and Found]]'' (Double Album, 1979, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Sequel (album)|Sequel]]'' (1980, Boardwalk Records) |

|||

* ''[[Anthology of Harry Chapin]]'' (1985, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Remember When the Music]]'' (1987, Dunhill Compact Classics) |

|||

* ''[[The Gold Medal Collection]]'' (1988, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[The Last Protest Singer]]'' (1988, Dunhill Compact Classics) |

|||

* ''[[Harry Chapin Tribute]]'' (1990, Relativity Records) |

|||

* ''[[The Bottom Line Encore Collection]]'' (1998, Bottom Line / Koch) |

|||

* ''[[Story of a Life]]'' (1999, Elektra) |

|||

* ''[[Heads and Tales]] / [[Sniper and Other Love Songs]]'' (2004, Elektra. Double CD re-release of first two albums with bonus tracks) |

|||

* ''[[Introducing: Harry Chapin]]'' (2006) |

|||

==Phonology== |

|||

{{IPA notice}} |

|||

:''For more specific information on phonology of Chinese see the respective main articles of each [[Chinese spoken language|spoken variety]].'' <!--I think this is about as specific we can get without making a looong and dull list of links--> |

|||

The [[phonology|phonological]] structure of each syllable consists of a [[syllable nucleus|nucleus]] consisting of a [[vowel]] (which can be a [[monophthong]], [[diphthong]], or even a [[triphthong]] in certain varieties) with an optional [[syllable onset|onset]] or [[syllable coda|coda]] [[consonant]] as well as a [[tone (linguistics)|tone]]. There are some instances where a vowel is not used as a nucleus. An example of this is in [[Cantonese]], where the [[nasal consonant|nasal]] [[sonorant]] consonants {{IPA|/m/}} and {{IPA|/ŋ/}} can stand alone as their own syllable. |

|||

===Singles=== |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

Across all the spoken varieties, most syllables tend to be open syllables, meaning they have no coda, but syllables that do have codas are restricted to {{IPA|/m/}}, {{IPA|/n/}}, {{IPA|/ŋ/}}, {{IPA|/p/}}, {{IPA|/t/}}, {{IPA|/k/}}, or {{IPA|/ʔ/}}. Some varieties allow most of these codas, whereas others, such as [[Mandarin Chinese|Mandarin]], are limited to only two, namely {{IPA|/n/}} and {{IPA|/ŋ/}}. [[Consonant cluster]]s do not generally occur in either the onset or coda. The onset may be an [[affricate consonant|affricate]] or a consonant followed by a [[semivowel]], but these are not generally considered consonant clusters. |

|||

The number of sounds in the different spoken dialects varies, but in general there has been a tendency to a reduction in sounds from [[Middle Chinese]]. The Mandarin dialects in particular have experienced a dramatic decrease in sounds and so have far more multisyllabic words than most other spoken varieties. The total number of syllables in some varieties is therefore only about a thousand, including tonal variation, which is only about an eighth as many as English<ref>DeFrancis (1984) p.42 counts Chinese as having 1,277 tonal syllables, and about 398 to 418 if tones are disregarded; he cites Jespersen, Otto (1928) Monosyllabism in English; London, p.15 for a count of over 8000 syllables for English.</ref>. |

|||

All varieties of spoken Chinese use [[tone (linguistics)|tones]]. A few dialects of north China may have as few as three tones, while some dialects in south China have up to 6 or 10 tones, depending on how one counts. One exception from this is [[Shanghainese]] which has reduced the set of tones to a two-toned [[pitch accent]] system much like modern Japanese. |

|||

A very common example used to illustrate the use of tones in Chinese are the four main tones of [[Standard Mandarin]] applied to the syllable "ma." The tones correspond to these five [[Chinese character|characters]]: |

|||

{{Ruby notice}} |

|||

*{{Ruby-zh-p|媽/妈|mā}} "mother" — '''high level''' |

|||

*{{Ruby-zh-p|麻|má}} "hemp" or "torpid" — '''high rising''' |

|||

*{{Ruby-zh-p|馬/马|mǎ}} "horse" — '''low falling-rising''' |

|||

*{{Ruby-zh-p|罵/骂|mà}} "scold" — '''high falling''' |

|||

*{{Ruby-zh-p|嗎/吗|ma}} "question particle" — '''neutral''' |

|||

{{Listen|filename=zh-pinyin_tones_with_ma.ogg|title=Listen to the tones|description=This is a recording of the four main tones. Fifth, or neutral, tone is not included.}} |

|||

==Phonetic transcriptions== |

|||

The Chinese had no uniform phonetic transcription system until the mid-20th century, although enunciation patterns were recorded in early [[rime book]]s and dictionaries. Early [[Sanskrit]] and [[Pali]] [[India]]n translators were the first to attempt describing the sounds and enunciation patterns of the language in a foreign language. After 15th century CE Jesuits and Western court missionaries’ efforts result in some rudimentary Latin transcription systems, based on the [[Nanjing Mandarin]] dialect. |

|||

===Romanization=== |

|||

{{main|Romanization of Chinese}} |

|||

[[Romanization]] is the process of transcribing a language in the [[Latin alphabet]]. There are many systems of romanization for the Chinese languages due to the Chinese's own lack of phonetic transcription until modern times. Chinese is first known to have been written in Latin characters by Western [[Christianity in China|Christian missionaries]] in the 16th century. |

|||

Today the most common romanization standard for Standard Mandarin is ''[[Hanyu Pinyin]]'' (漢語拼音/汉语拼音), often known simply as pinyin, introduced in 1956 by the [[People's Republic of China]], later adopted by [[Singapore]] (see [[Chinese language romanisation in Singapore]]). Pinyin is almost universally employed now for teaching standard spoken Chinese in schools and universities across [[Americas|America]], [[Australia]] and [[Europe]]. Chinese parents also use Pinyin to teach their children the sounds and tones for words with which the child is unfamiliar. The Pinyin is usually shown below a picture of the thing the word represents, and alongside the Pinyin is the Chinese symbol.[Teach Yourself Mandarin Chinese-Elizabeth Scurfield] |

|||

The second-most common romanization system, the [[Wade-Giles]], was invented by Thomas Wade in 1859, later modified by Herbert Giles in 1892. As it approximates the phonology of Mandarin Chinese into English consonants and vowels (hence an [[Anglicization]]), it may be particularly helpful for beginner speakers of native English background. Wade-Giles is found in academic use in the [[United States]], particularly before the 1980s, and until recently was widely used in Taiwan ([[Taipei]] city now officially uses ''Hanyu Pinyin'' and the rest of the island officially uses ''Tōngyòng Pinyin'' 通用拼音/通用拼音). |

|||

When used within European texts, the [[Tone (linguistics)|tone]] transcriptions in both pinyin and Wade-Giles are often left out for simplicity; Wade-Giles' extensive use of apostrophes is also usually omitted. Thus, most Western readers will be much more familiar with ‘Beijing’ than they will be with ‘Běijīng’ (pinyin), and with ‘Taipei’ than ‘T'ai²-pei³’ (Wade-Giles). |

|||

Here are a few examples of ''Hanyu Pinyin'' and Wade-Giles, for comparison:<!-- Please feel free to add Yale, Postal or whatever other examples you know, but I don't know those systems. [[User:Jiawen|Jiawen]] 07:27, 3 Jun 2005 (UTC) --> |

|||

{|class="wikitable" |

|||

|+'''Mandarin Romanization Comparison''' |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

! style="background:#efefef;"|Characters !! style="background:#efefef;"|Wade-Giles !! style="background:#efefef;"|Hanyu Pinyin !! style="background:#efefef;"|Notes |

|||

!Year !! Song Title !! Highest US<br> [[Billboard Hot 100|Chart Position]] |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|中国/中國||Chung<sup>1</sup>-kuo²||Zhōngguó||"China" |

|||

| 1972 || "[[Taxi (song)|Taxi]]" || align="center" | #24 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|北京||Pei³-ching<sup>1</sup>||Běijīng||Capital of the People's Republic of China |

|||

| 1972 || "[[Sniper (song)|Sniper]]" || align="center" | - |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|台北||T'ai²-pei³||Táiběi||Capital of the Taiwan |

|||

| 1972 || "[[Sunday Morning Sunshine]]" || align="center" | #75 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|毛泽东/毛澤東||Mao² Tse²-tung<sup>1</sup>||Máo Zédōng||Former Communist Chinese leader |

|||

| 1972 || "[[A Better Place to Be (Harry Chapin song)|A Better Place to Be]]" || align="center" | #86 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|蒋介石/蔣介石||Chiang³ Chieh<sup>4</sup>-shih²||Jiǎng Jièshí||Former Nationalist Chinese leader (better known to English speakers as [[Chiang Kai-shek]], a romanisation) |

|||

| 1974 || "[[W*O*L*D]]" || align="center" | #36 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1974 || "[[Mr. Tanner]]" || align="center" | - |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1974 || "[[Cat's in the Cradle]]" || align="center" | '''#1''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1974 || "[[I Wanna Learn A Love Song]]" || align="center" | #44 |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1978 || "[[Flowers Are Red]]" || align="center" | - |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1980 || "[[Taxi (song)|Sequel]]" || align="center" | #23 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|孔子||K'ung³ Tsu³||Kǒng Zǐ||"Confucius" |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

Other systems of romanization for Chinese include the [[École française d'Extrême-Orient]], the [[Yale]] (invented during WWII for US troops), as well as separate systems for [[Cantonese]], [[Minnan]], [[Hakka]], and other Chinese languages or dialects. |

|||

== Video / DVD releases == |

|||

* ''The Book Of Chapin'' |

|||

===Other phonetic transcriptions=== |

|||

* ''You Are The Only Song (also known as The Final Concert)'' |

|||

Chinese languages have been phonetically transcribed into many other writing systems over the centuries. The [[Phagspa characters|phagspa script]], for example, has been very helpful in reconstructing the pronunciations of pre-modern forms of Chinese. |

|||

* ''Rockpalast Live'' |

|||

* ''Remember When: The Anthology'' |

|||

[[Zhuyin]] (注音, also known as ''bopomofo''), a [[katakana]]-inspired [[syllabary]] is still widely used in Taiwan's [[elementary school]]s to aid standard pronunciation. Although bopomofo characters are reminiscent of katakana script, there is no source to substantiate the claim that Katakana was the basis for the zhuyin system. A comparison table of zhuyin to pinyin exists in the [[Zhuyin#Zhuyin vs. Tongyong Pinyin & Hanyu Pinyin|zhuyin article]]. Syllables based on pinyin and zhuyin can also be compared by looking at the following articles: |

|||

*[[Pinyin table]] |

|||

*[[Zhuyin table]] |

|||

There are also at least two systems of [[cyrillization]] for Chinese. The most widespread is the [[Cyrillization of Chinese from Pinyin|Palladius system]]. |

|||

==Grammar and morphology== |

|||

{{main|Chinese grammar}} |

|||

Modern Chinese has often been erroneously classed as a "monosyllabic" language. While most of the [[morpheme]]s are single [[syllable]], modern Chinese today is much less a monosyllabic language in that [[noun]]s, [[adjective]]s and [[verb]]s are largely di-syllabic. The tendency to create disyllabic words in the modern Chinese languages, particularly in Mandarin, has been particularly pronounced when compared to [[Classical Chinese]]. Classical Chinese is a highly [[isolating language]], with each idea (morpheme) generally corresponding to a single syllable and a single character; Modern Chinese though, has the tendency to form new words through disyllabic, trisyllabic and tetra-character [[agglutination]]. In fact, some linguists argue that classifying modern Chinese as an isolating language is misleading, for this reason alone. |

|||

Chinese [[morphology (linguistics)|morphology]] is strictly bound to a set number of [[syllable]]s with a fairly rigid construction which are the [[morpheme]]s, the smallest blocks of the language. While many of these single-syllable morphemes ('' zì'', 字 in Chinese) can stand alone as individual [[word (linguistics)|words]], they more often than not form multi-syllabic [[compound]]s, known as ''cí'' (词/詞), which more closely resembles the traditional Western notion of a word. A Chinese ''cí'' (“word”) can consist of more than one character-morpheme, usually two, but there can be three or more. |

|||

For example: |

|||

*''Yun'' 云 -“cloud” |

|||

*''Hanbaobao'' 汉堡包 –“hamburger” |

|||

*''Wo'' 我 –“I, me” |

|||

*''Renmin'' 人民 –“people” |

|||

*''Diqiu'' 地球 –“earth(globosity)” |

|||

*''Shandian'' 闪电 –“lightning” |

|||

*''Meng'' 梦 –“dream” |

|||

All varieties of modern Chinese are [[analytic language]]s, in that they depend on [[syntax]] (word order and sentence structure) rather than [[Morphology (linguistics)|morphology]] — i.e., changes in form of a word — to indicate changes in meaning. In other words, Chinese has next to no [[grammatical inflection]]s – it possesses no [[tense]]s, no [[grammatical voice|voice]]s, no [[number]]s (singular, plural; though there are plural markers), only a few [[Article (grammar)|article]]s (i.e., equivalents to "the, a, an" in English), and no [[gender]]. |

|||

They make heavy use of [[grammatical particle]]s to indicate [[grammatical aspect|aspect]] and [[grammatical mood|mood]]. In Mandarin Chinese, this involves the use of particles like le 了, hai 还, yijing 已经, etc. |

|||

Chinese features [[Subject Verb Object]] [[word order]], and like many other languages in [[East Asia]], makes frequent use of the [[topic-comment]] construction to form sentences. Chinese also has an extensive system of [[measure word]]s, another trait shared with neighbouring languages like [[Japanese language|Japanese]] and [[Korean language|Korean]]. See '''[[Chinese measure words]]''' for an extensive coverage of this subject. |

|||

Other notable grammatical features common to all the spoken varieties of Chinese include the use of [[serial verb construction]], [[pro-drop language|pronoun dropping]] and the related [[null subject language|subject dropping]]. |

|||

Although the grammars of the spoken varieties share many traits, they do possess differences. See '''[[Chinese grammar]]''' for the grammar of [[Standard Mandarin]] (the standardized Chinese spoken language), and the articles on other varieties of Chinese for their respective grammars. |

|||

===Tones and homophones=== |

|||

Official modern Mandarin has only 400 spoken monosyllables but over 10,000 written characters, so there are many [[homophone]]s only distinguishable by the four tones. Even this is often not enough unless the context and exact phrase or cí is identified. |

|||

The mono-syllable ''jī'', first tone in [[standard Mandarin]], corresponds to the following characters: 雞/鸡 ''chicken'', 機/机 ''machine'', 基 ''basic'', 擊/击 ''(to) hit'', 饑/饥 ''hunger'', and 積/积 ''sum''. In speech, the glyphing of a monosyllable to its meaning must be determined by context or by relation to other morphemes (e.g. "some" as in the opposite of "none"). Native speakers may state which words or phrases their names are found in, for convenience of writing: 名字叫嘉英,嘉陵江的嘉,英國的英 Míngzi jiào Jiāyīng, Jiālíng Jiāng de jiā, Yīngguó de yīng "My name is Jiāyīng, the ''Jia'' for ''[[Jialing River]]'' and the ''ying'' for ''the short form in Chinese of [[United Kingdom|UK]]''." |

|||

Southern Chinese varieties like Cantonese and Hakka preserved more of the [[syllable rime|rimes]] of Middle Chinese and have more tones. The previous examples of ''jī'', for instance, for "stimulated", "chicken", and "machine", have distinct pronunciations in Cantonese (romanized using [[jyutping]]): ''gik1'', ''gai1'', and ''gei1'', respectively. For this reason, southern varieties tend to employ fewer multi-syllabic words. |

|||

==Vocabulary== |

|||

The entire Chinese character corpus since antiquity comprises well over 20,000 characters, of which only roughly 10,000 are now commonly in use. However Chinese characters should not be confused with Chinese words, there are many times more Chinese words than there are characters as most Chinese words are made up of two or more different characters. |

|||

Estimates of the total number of Chinese words and phrases vary greatly. The ''[[Hanyu Da Zidian]]'', an all-inclusive compendium of Chinese characters, includes 54,678 head entries for characters, including [[bone oracle]] versions. The ''[[Zhonghua Zihai]]'' 中华字海 (1994) contains 85,568 head entries for character definitions, and is the largest reference work based purely on character and its literary variants. |

|||

The most comprehensive pure linguistic Chinese-language dictionary, the 12-volumed ''[[Hanyu Da Cidian]]'' 汉语大词典, records more than 23,000 head Chinese characters, and gives over 370,000 definitions. The 1999 revised ''[[Cihai]]'', a multi-volume encyclopedic dictionary reference work, gives 122,836 vocabulary entry definitions under 19,485 Chinese characters, including proper names, phrases and common zoological, geographical, sociological, scientific and technical terms. |

|||

The latest 2007 5th edition of ''[[Xiandai Hanyu Cidian]]'' 现代汉语词典, an authoritative one-volume dictionary on modern standard Chinese language as used in [[mainland China]], has 65,000 entries and defines 11,000 head characters. In Taiwan it is also proven that the Chinese language has 7 different tones. |

|||

==New words== |

|||

Like any other language, Chinese has absorbed a sizeable amount of loanwords from other cultures. Most Chinese words are formed out of native Chinese morphemes, including words describing imported objects and ideas. However, direct phonetic borrowing of foreign words has gone on since ancient times. |

|||

Words borrowed from along the [[Silk Road]] since [[Old Chinese]] include 葡萄 "[[grape]]," 石榴 "[[pomegranate]]" and 狮子/獅子 "[[lion]]." Some words were borrowed from Buddhist scriptures, including 佛 "Buddha" and 菩萨/菩薩 "bodhisattva." Other words came from nomadic peoples to the north, such as 胡同 "[[hutong]]." Words borrowed from the peoples along the Silk Road, such as 葡萄 "grape" (pútáo in Mandarin) generally have [[Persia]]n etymologies. Buddhist terminology is generally derived from [[Sanskrit]] or [[Pāli]], the [[liturgical language]]s of [[North India]]. Words borrowed from the nomadic tribes of the [[Gobi]], Mongolian or northeast regions generally have [[Altaic]] etymologies, such as 琵笆 or 酪 "cheese" or "yoghurt", but from exactly which Altaic source is not always entirely clear. |

|||

===Modern borrowings and loanwords=== |

|||

Foreign words continue to enter the Chinese language by transcription according to their pronunciations. This is done by employing Chinese characters with similar pronunciations. For example, "Israel" becomes 以色列 (pinyin: yǐsèliè), Paris 巴黎. A rather small number of direct transliterations have survived as common words, including 沙發 ''shāfā'' "sofa," 马达/馬達 ''mǎdá'' "motor," 幽默 ''yōumò'' "humour," 逻辑/邏輯 ''luójí'' "logic," 时髦/時髦 ''shímáo'' "smart, fashionable" and 歇斯底里 ''xiēsīdǐlǐ'' "hysterics." The bulk of these words were originally coined in the [[Shanghainese]] dialect during the early 20th century and were later loaned into Mandarin, hence their pronunciations in Mandarin may be quite off from the English. For example, 沙发/沙發 and 马达/馬達 in Shanghainese actually sound more like the English "sofa" and "motor." |

|||

Today, it is much more common to use existing Chinese morphemes to coin new words in order to represent imported concepts, such as technical expressions. Any [[Latin]] or [[Greek language|Greek]] etymologies are dropped, making them more comprehensible for Chinese but introducing more difficulties in understanding foreign texts. For example, the word ''telephone'' was loaned phonetically as 德律风/德律風 ( [[Shanghainese]]: ''télífon'' [{{IPA|təlɪfoŋ}}], [[Standard Mandarin]]: ''délǜfēng'') during the 1920s and widely used in Shanghai, but later the Japanese 电话/電話 (''diànhuà'' "electric speech"), built out of native Chinese morphemes, became prevalent. Other examples include 电视/電視 (''diànshì'' "electric vision") for television, 电脑/電腦 (''diànnǎo'' "electric brain") for computer; 手机/手機 (''shǒujī'' "hand machine") for cellphone, and 蓝牙/藍芽 (''lányá'' "blue tooth") for [[Bluetooth]]. 網誌(''wǎng zhì''"internet logbook") for blog in Cantonese or people in [[Hong Kong]] and [[Macau]]. Occasionally half-transliteration, half-translation compromises are accepted, such as 汉堡包/漢堡包 (''hànbǎo bāo'', "''Hamburg'' bun") for ''hamburger.'' Sometimes translations are designed so that they sound like the original while incorporating Chinese morphemes, such as 拖拉机/拖拉機 (''tuōlājī'', "tractor," literally "dragging-pulling machine"), or 马利奥/馬利奧 for the video game character ''[[Mario]].'' This is often done for commercial purposes, for example 奔腾/奔騰 (''bēnténg'' "running leaping") for [[Pentium]] and 赛百味/賽百味 (''Sàibǎiwèi'' "better-than hundred tastes") for [[Subway (restaurant)|Subway restaurants]]. |

|||

Since the 20th century, another source has been [[Japan]]. Using existing [[kanji]], which are Chinese characters used in the [[Japanese language]], the Japanese re-moulded European concepts and inventions into ''[[wasei-kango]]'' (和製漢語, literally ''Japanese-made Chinese''), and re-loaned many of these into modern Chinese. Examples include ''diànhuà'' (电话/電話, denwa, "telephone"), ''shèhuì'' (社会, shakai, "society"), ''kēxué'' (科学/科學, kagaku, "science") and ''chōuxiàng'' (抽象, chūshō, "abstract"). Other terms were coined by the Japanese by giving new senses to existing Chinese terms or by referring to expressions used in classical Chinese literature. For example, ''jīngjì'' (经济/經濟, keizai), which in the original Chinese meant "the workings of the state", was narrowed to "economy" in Japanese; this narrowed definition was then reimported into Chinese. As a result, these terms are virtually indistinguishable from native Chinese words: indeed, there is some dispute over some of these terms as to whether the Japanese or Chinese coined them first. As a result of this toing-and-froing process, Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese share a corpus linguistics of terms describing modern terminology, in parallel to a similar corpus of terms built from Greco-Latin terms shared among European languages. [[Taiwanese]] and [[Taiwanese Mandarin]] continue to be influenced by Japanese eg. 便当/便當 “lunchbox or boxed lunch” (from [[bento]]) and 料理 “prepared cuisine”, have passed into common currency. |

|||

Western foreign words have great influence on Chinese language since the 20th century, through [[transliteration]]s. From [[French language|French]] came 芭蕾 (''bāléi'', "ballet"), 香槟 (''xiāngbīn'', "champagne"), via [[Italian language|Italian]] 咖啡 (''kāfēi'', "caffè"). The English influence is particularly pronounced. From early 20th century [[Shanghainese]], many English words are borrowed .eg. the above-mentioned 沙發 (''shāfā'' "sofa"), 幽默 (''yōumò'' "humour"), and 高尔夫 (''gāoěrfū'', "golf"). Later [[US]] [[soft influence]]s gave rise to 迪斯科 (''dísīkè'', "disco"), 可乐 (''kělè'', "cola") and 迷你 (''mínǐ'', "mini(skirt)"). Contemporary colloquial [[Cantonese]] has distinct loanwords from English like cartoon 卡通 (cartoon), 基佬 (gay people), 的士 (taxi), 巴士 (bus). With the rising popularity of the Internet, there is a current vogue in China for coining English transliterations, eg. 粉絲 (''fěnsī'', "fans"), 駭客 (''hèikè'', "[[Hacker (computer security)|hacker]]"), 部落格(''bùluōgé'',blog) in [[Taiwanese Mandarin]]. |

|||

==Learning Chinese== |

|||

{{See also|Chinese as a foreign language}} |

|||

Since China’s economic and political rise in recent years, standard Chinese has become an increasingly popular subject of study amongst the young in the Western world, as in the UK.<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/magazine/4617646.stm BBC NEWS | UK | Magazine | How hard is it to learn Chinese?<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

|||

In 1991 there were 2,000 foreign learners taking China's official [[Chinese Proficiency Test]] (comparable to English's [[University of Cambridge ESOL examination|Cambridge Certificate]]), while in 2005, the number of candidates had risen sharply to 117,660{{Fact|date=June 2008}}. |

|||

Chinese is a popular language; the approximate number of learners all around the world is predicted to be 100 million in 2010{{Fact|date=June 2008}} |

|||

Chinese is one of the 6 official languages of the UN. To learn Mandarin Chinese is a fashion nowadays worldwide, while the best way to learn standard Chinese is to come to Beijing of course, but will cost a lot. Thus, distance teaching and learning becomes popular and does great help. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{Portal|China|TempleofHeaven-HallofPrayer.jpg}} |

|||

<div class="references-small" style="-moz-column-count:2; column-count:2;"> |

|||

*[[Chinese characters]] |

|||

*[[Chinese honorifics]] |

|||

*[[Chinese measure word]] |

|||

*[[Chinese number gestures]] |

|||

*[[Chinese numerals]] |

|||

*[[Four-character idiom]] |

|||

*[[Han unification]] |

|||

*[[Haner language]] |

|||

*[[HSK test]] |

|||

*[[Languages of China]] |

|||

*[[Nü shu]] |

|||

</div> |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

*{{cite book|authorlink=John DeFrancis|last=DeFrancis|first=John|title=The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy|publisher=University of Hawaii Press|year=1984|id=ISBN 0-8248-1068-6}} |

|||

{{Refimprove|date=February 2008}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Hannas, William C.|title=Asia's Orthographic Dilemma|publisher=University of Hawaii Press|year=1997|id=ISBN 0-8248-1892-X}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Norman, Jerry|title=Chinese|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=1988|id=ISBN 0-521-29653-6}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Qiu, Xigui|title=Chinese Writing|publisher=Society for the Study of Early China and Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley|year=2000|id=ISBN 1-55729-071-7}} |

|||

*{{cite book|author=Ramsey, S. Robert|title=The Languages of China|publisher=Princeton University Press|year=1987|id=ISBN 0-691-01468-X}} |

|||

==Footnotes== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

== |

==External links== |

||

{{InterWiki|code=zh}} |

|||

{{Commons|Harry Chapin}} |

|||

* [http://foundationcenter.org/grantmaker/harrychapin/ Harry Chapin Foundation] |

|||

===Dictionaries=== |

|||

* [http://www.harrychapinmusic.com/ Website by the Chapin family] |

|||

* ''Grand dictionnaire Ricci de la langue chinoise''. 7 volumes. Instituts Ricci (Paris – Taipei). Desclée de Brouwer. 2001. ISBN 2-220-04667-2. Chinese to French (by far the largest dictionary of Chinese in a European language). |

|||

* {{imdb name|id=0152166|name=Harry Chapin}} |

|||

* ''ABC Chinese-English Comprehensive Dictionary''. Editor: John de Francis. (2003) University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 0-8248-2766-X. Excellent Chinese to English dictionary arranged according to pinyin romanisation. |

|||

* [http://www.licares.org/Our_Founder.htm Harry Chapin (founder) page on Long Island Cares/Harry Chapin Food Bank website] |

|||

* ''ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese''. Axel Schuessler. 2007. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu. ISBN 978-08248-2975-9. |

|||

* [http://harrychapin.com/ HarryChapin.com] - a fan site |

|||

{{External links|{{CURRENTMONTHNAME}} {{CURRENTYEAR}}}} |

|||

* [http://www.classicbands.com/chapin.html Harry Chapin at classicbands.com] - Contains many details about the accident that took his life. |

|||

*[http://www.chinglish.com CHINGLISH] online Chinese <-> English Dictionary |

|||

* [http://worldhungeryear.org/ World Hunger Year website] |

|||

*[http://www.nciku.com nciku] free online Chinese dictionary with handwriting recognition, pinyin, sound clips, etc. |

|||

* [http://www.bthsalum.org/hall_%20inductees%2000.htm Harry Chapin] |

|||

*[http://www.mdbg.net/chindict/chindict.php?page=chardict MDBG free online Chinese-English dictionary] |

|||