Alexei Mikhailovich Gan

Alexei Gan ( Russian Алексей Михайлович Ган ; scientific. Transliteration Aleksej Michajlovič Gan; * probably 1887 around Moscow , Russian Empire , † 8. September 1942 in an unknown location) was a Russian- Soviet avant-garde Artists, Art , Film and theater theorist , graphic designer and filmmaker .

Initially primarily active in the theater, around 1920 he developed from this the mass action as a modern and proletarian art form, in which the differences between art and life as well as between artist and viewer are to be eliminated. In 1921 he was a co-founder of the First Working Group of the Constructivists and pioneered the development and theoretical formulation of constructivism . In his book Konstruktiwism ( German Constructivism) from 1922, Gan formulated one of the most widely noticed manifestos of the Russian avant-garde.

Gan created a radical art theory that rejected the classical arts like painting or sculpture and called for the use of new, more contemporary artistic means of expression; Mass action, room construction, film and ( graphic ) design played a central role here . According to Gan, only these can be viewed as a contemporary artistic form of a socialist society. Central to the rejection of historical art forms was their lack of relation to everyday life. Goose's main interest was in breaking the separation between art and life. The “socialist city” was the ultimate goal of all artistic endeavors.

Life

Childhood and youth up to the revolution

| Self portrait |

|---|

| Alexei Gan; 1910s |

| Pencil on cardboard |

| Russian State Archives for Literature and Art; Moscow

linked image |

Gan was probably born in the Moscow area in 1887. He probably came from a not particularly wealthy but educated family. His family name Gan is the Russian form of the German name Hahn . Otherwise nothing is known about his family and origins.

There is little information about his activities before the revolution. He may have been active in an underground anarchist movement with theater ties before and during World War I. There is also evidence that he studied at an art school before the war. A self-portrait by Gan from the 1910s has survived, which shows symbolist influences. During the war he was also a soldier .

Work in anarchist movements

After the revolution, Gan was active in the food workers' union and, presumably, in anarchist movements. In August 1917 he organized a small proletarian theater group at the food workers' union . In December, Gan organized a meeting to make the theater group a broader movement, which was only moderately successful. He called this the Proletarian Theater . About thirty to forty people attended the meeting. At the end of February 1918 he organized a much larger conference on this subject, this time. The Moscow section of Proletkult had just been founded, but Gan decided to place his theater group under the administration of the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups , as Proletkult was too centralized for him.

In January 1918 he organized the magazine Revolutionäres Schaffen with, of which only one issue appeared in which he did not publish an article. Gans articles were scheduled for the second issue, which never appeared. Gan then wrote from March 1918 for the anarchist newspaper Anarchija , which was published by the Moscow Federation of Anarchist Groups . He introduced a small art section there, where he reported on current events and wrote articles about his view of art and especially of theater. Gan also gave lectures on the premises of the Federation and was also politically active in it. He campaigned for the confiscation of private palaces and their art collections. These buildings were made accessible to the public and converted into museums and workspaces for artists and political groups. Gan led the group for the seizure of the Morosow house. During this time, Gan came into contact with other avant-garde artists who have now also published in Anarchija. These included Kazimir Malevich , Alexei Morgunow , Alexander Rodchenko , Olga Rosanova and Vladimir Tatlin .

From April to September 1918 there was repression against anarchists by the Bolshevik government. Many members of the Federation were arrested, and from July 1918 onwards, Anarchija ceased to appear. Gans proletarian theater group lost their rehearsal rooms and the Morosow house was used by Proletkult. Goose's last recorded activity before joining the state arts organizations was attending a meeting of the food workers' union on August 10, 1918.

Work for state arts organizations

Gan joined the Communist Party in 1918 , probably between August and December. From December 1918 he was responsible for cultural affairs in a local Red Army organization . He was responsible for the coordination of cultural organizations. As part of this task, he sent books and theater groups to the front to support the soldiers there. Gan's move to a government agency was probably largely due to political circumstances. It was simply no longer possible to form anarchist groups and work there. In addition, it was a strategy of many anarchists to get involved in the Bolshevik associations in order to promote a second, anarchist revolution. So they kept Bolshevism closer to their position than any other regime before. Gan was involved in the organization and design of the May festivities in 1919 and brought in his criticism the previous year. The celebrations became less of a staged spectacle and more of a public street festival. Gan planned another public event for August 17, Soviet Propaganda Day , which was canceled. However, various materials were produced for the event. These were gramophone records and a booklet with slogans, which supposedly had a circulation of 2.5 million, but this can be doubted. The booklet begins with the words:

“The tsars thought: You can't enlighten people (otherwise it would be impossible to control them). (Words from Catherine II. )

The Soviet power thinks: Enlightenment is necessary so that people can govern themselves. "

In the course of 1918 he went to the theater department (abbreviation TEO) of the People's Commissariat for Education of the RSFSR (abbreviation NARKOMPROS). He worked there at the Workers 'Peasants' Theater Association within a section of the TEO, the section for workers 'peasants' theater . During this time he pursued the idea of mass action and the group decided in November 1919 to support him at the workers-farmers-theater congress. Overall, however, the workers-farmers-theater association with its idea of mass action was a minority at the congress. The other groups wanted to keep traditional forms of theater, but to open them up to workers and peasants and to have the state supported. Here, however, Gan found himself in a paradoxical position. Mass actions should be events that, in addition to careful control, have a large proportion of spontaneous participation by the masses. It was not, however, the case that Gan's view was the idea of the majority who preferred normal theater.

In October 1919 a new section of the TEO was approved, the section for mass performances and spectacles , which was established from December. Valentin Smyshaliaev von Proletkult was appointed director of the section . Other members were P. Kogan, M. Libakow, N. Lwow and Gan. The section was responsible for organizing the May festivities in 1920, which were also canceled due to financial and personal problems of the group. The theoretical conceptions for May 1920 are, however, important for the development of mass action. Gan arranged for all materials to be published.

At the end of February 1920 his first wife Olga died, with whom he had a child, Katja. She was raised by his wife's relatives in Ukraine from childhood .

During 1920 he wrote the drama We , which was based on the novel of the same name by Yevgeny Zamyatin . The novel, which inspired both Aldous Huxley for Brave New World and George Orwell for 1984 , is about a 29th century society where all aspects of life - work, leisure and even sex - are governed by a dictator. People's names have been replaced by a combination of a letter and three digits. The two protagonists of the novel flee to a remote area that is not under the dictator's command. However, they are caught and brainwashed. This will bring them back to their normal conformist life. Alexander Rodchenko designed the costumes for the play, but it was never performed. The fact that Zamyatin's novel was banned in the Soviet Union probably also played a role. The fact that Gan wrote this piece shows how much he still represented anarchist ideas during his work in the state Soviet offices.

First working group of constructivists and constructivism

On May 5, 1920, Alexei Gan was admitted to the fourth general assembly of the INChUK , the Institute for Artistic Culture, on the recommendation of Alexander Rodchenko . The INChUK was a discussion space where various painters, graphic designers, sculptors, architects and art scholars tried to determine the problems and future of artistic experiments in post-revolutionary Russia . The INChUK consisted of various working groups in which artistic issues were discussed. Gan did not join any of these actual working groups, but worked in a commission that dealt with the development of the theoretical program of the INChUK. There were less specific artistic problems discussed, but how art fits into social processes, values and demands. Around the same time, Gan was working for the Arts Section (ISO) of NARKOMPROS on art brochures, of which it is unclear whether they ever appeared. Presumably this project became his book Konstruktiwism .

Gan claimed in 1922 that the Constructivist First Working Group was formed in December 1920. There is little evidence that he, Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova first formulated constructivist ideas during this period. However, this must be considered speculative. The group was not really founded until 1921. On February 23, 1921, Rodchenko, Stepanova and Gan met outside the INChUK to discuss who could become potential members. The group's first official meeting dates back to March 18, 1921, when Rodchenko, Stepanova, Karl Ioganson and Georgi Stenberg decided whether Gan, Konstantin Medunetzki and Wladimir Stenberg should be accepted into the group. This somewhat paradoxical circumstance can perhaps be explained by the fact that Gan was not present at the discussions of the INChUK beforehand and was only known privately to Rodchenko and Stepanova. The group rejected the fine arts in favor of graphic design, industrial production, photography, and film . Gan formulated the group's program, which was held on March 28, 1921 ( On the Program and Work Plan of the Constructivist Group ) and adopted on April 1, 1921.

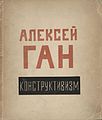

In the summer of 1922 he published his book Konstruktiwism (Constructivism), with which he published his radical art theory in great clarity. With its unusual typographic design, which is not yet based on photosetting , the book is the first constructivist object that Gan created. Gan saw it as a political agitation pamphlet in the tradition of Nikolai Bukharin's The ABC of Communism . With a print run of 2,000 copies, however, the effect outside of artistic circles cannot be compared with, for example, Bukharin's work.

In August 1922 he founded the first Soviet film magazine Kino-Foto. Cinematographic and photographic journal ( Russian Кино-Фот. Журнал кинематографии и фотографии Kino-fot. Schurnal kinematografii i fotografii ). Here, too, he placed himself at the forefront of the avant-garde with his essay Kinematograf i kinomategrafija ( German cinema and kinomategraphie), which appeared in the first issue. Gan explains his film theory here. Accordingly, modern Soviet film must be radically different from bourgeois film. It was therefore not the task of the film to invent situations and actions, but to take them directly from life. With that he went very close to Dsiga Wertow , with whom, however, it broke in 1924. After only six issues, the magazine was discontinued with the last issue on January 8, 1923.

After differences with the other members of the Constructivist Working Group, all members (except Gan) resigned from the First Constructivist Working Group by 1923 . From December 1923 on, Gan met with some young artists for a second constructivist working group . Members were Viktor Shestakov , Galina and Olga Tschitschagowa , N. Smirnow, Grigori Miller , Alexandra Mirolyubova and L. Sanina.

During the twenties, Gan had an informal relationship with WChUTEMAS , although he was never permanently employed as a teacher, he gathered a certain group of students who wanted to learn the technical processes of printing, for example. Gan was probably never employed because the rector Vladimir Faworski did not want the influence of the productivists to become too great. In 1924, Gan took part in the first discussion exhibition of the associations of active revolutionary art in an outside exhibition room of the WChUTEMAS with some students from WChUTEMAS, who were now members of the Second Working Group of the Constructivists . For the exhibition catalog he wrote a manifesto for the group. They exhibited children's books, work clothes, designs for tables and kiosks there.

In 1923 he was associated with LEF magazine . In 1924 Gan shot the documentary The Island of Young Pioneers himself .

In 1924 Gan resigned from the Communist Party.

In the twenties and early thirties he lived with the film director Esfir Schub .

Work at the OSA

In April and May 1925 he took part in the First Exhibition of the Movie Poster and in 1926 in the First Graphic Exhibition in Moscow. In 1926 he joined the OSA (Association of Contemporary Architects). From 1926 to 1928 he was art director of the magazine SA (contemporary architecture) of the OSA, whose title pages he designed with few exceptions during this time. He was also involved in the organization of the OSA's First Modern Architecture Exhibition in Moscow in 1927. He was responsible for the installation of the works and the design of the poster.

In autumn 1927 he was admitted to the Donskaya Neuropsychiatric Hospital because of nervous exhaustion and alcohol addiction. Nevertheless, in 1928 he was one of the founding initiators of the Oktjabr (German October) association, which existed until around 1932. In May 1929 he was a speaker at the first OSA Congress.

End of artistic activity

In 1931 he was in Khabarovsk . From 1935 he stayed again in Khabarovsk in the hope of being able to work as an architect.

In October 1941 he was arrested in the course of the " Stalin Purges " for participating in " counter-revolutionary propaganda and agitation ", found guilty in August 1942 and killed on September 8, 1942 in an unknown location. He was rehabilitated in 1989.

Goose art theory and work

Goose's art theory can be divided into two phases, the latter building on the former. The first phase represents his theory about theater and mass actions, which is strongly influenced by anarchist views. The second, constructivist phase adopts many of these elements, but complements them and places them on a Marxist basis.

Theater and mass actions (until around 1920)

Goose art concept

In his writings for Anarchija, for which he wrote from March to July 1918, Gan always used the word творчество twortschestwo and not искусство iskusstwo for the word art . Tvochestwo means work or creation , while iskusstwo means art in its classical historical sense, also etymologically in its relationship to the Russian words for artificiality , while tvichestwo is linguistically related to make , created . So while iskusstwo changes material to create an artificial illusion, with twortschestwo reality itself is changed. Gan was not the only one who represented this new conception of art, nor was it its inventor, Platon Kerschenzew wrote a book called Tvicheskii teatr (Created Thater) in 1918 and the poets Dawid Burljuk , Nikolai Assejew and Sergei Tretyakov were active for the journal Tvichestwo (work). The revolution was seen as a "social twortschestwo ". Tvochestvo , i.e. creation, is the central human drive that determines the arts, language and politics. Compared to earlier analyzes, such as those represented by Immanuel Kant in the Critique of Judgment , which also assume that the aesthetic and political dimensions follow a common dynamic, the avant-garde demand was to put the mass as the subject in this process. Gans's artistic hope was that the masses would no longer be the consumers of the art of an elite, be it the bourgeoisie or the avant-garde, but that both the production and consumption of art would merge into an inseparable unit. Mass action must also be understood from this theoretical conception.

It was from this idea that Gan formulated his theater theory. Gan made a distinction between igrat (actors) and deistwowat (act, act). The former denotes the theater of the bourgeoisie in Russian, while the latter is the root word for the term for amateur theater. Gan saw amateur theater as an actually proletarian art form. While the theater of the bourgeoisie only consists in artificially imitating a scene in an artificial location according to a fixed script, for Gan the aim of proletarian theater is not to imitate when acting, but to act naturally, i.e. the barrier between the sphere of one to lift the artificial theater world and to locate the theater in life itself.

From this conception Gan created his formulation of the theory of mass actions. The basic idea is to generate and carefully control spontaneous events in public space with the crowds there. So it ties in with the theoretical basis of the terms deistwowat , that is Gan's theory of the proletarian theater, as well as with twortschestwo , that is , to shape the production and consumption of an art form into an inseparable unit. From today's point of view, the mass action can be imagined like a spontaneous festival .

Gan in his essay The Struggle for Mass Action from 1922 on the theoretical basis of mass action:

"[...] the mass action is not an invention or a fantasy, but an absolute and natural necessity that comes from the deep essence of communism [...] the mass action in communism is not the action of a bourgeois society, but a human one - the material one Production will merge with intellectual production. This intellectual / material culture mobilizes all of its strengths and resources in order not only to subordinate nature, but also the entire, universal cosmos. "

In the amalgamation of intellectual and material culture, Gan sees the abolition of the difference between the production and consumption of culture and thus a new, truly proletarian art. An art that is not produced by a bourgeois society, but is both produced and experienced by all people at the same time. This position also explains the reason why Gan wrote for an anarchist newspaper and why he rejected the May festivities in 1918 and did not attend. He saw the May festivities as a spectacle planned by the Bolshevik government, which only expresses rule over workers, but does not show the rule of workers.

One of the first mass actions carried out was Nikolai Jewreinov's mass action Storming the Winter Palace . At this spectacle, Jewreinow staged the storming of the Winter Palace with thousands of amateur actors . Gan rejected Jewreinow's action, however, because he used the Winter Palace as a stage, in front of which a fixed play was performed with actors. With Gan, on the other hand, the action takes place in such a way that it is impossible to watch the action as a spectator, as it extends spatially throughout the city. Every viewer automatically becomes a participant, which is not the case with Jewreinow.

May festivities in 1920

Though not carried out, the May festivities planned by Gan and the Section for Mass Performances and Spectacles for 1920 are the culmination of Gan's exploration of the subject and also the most well-documented. The actual plan came from Gan, the ideas of the other members were largely discarded.

The plan for the event was to rename all places in Moscow during May Day according to different arts or sciences, and decorate them to suit each. This should represent a “socialist city of the future”. So there should be a geography space that would be adorned with a huge globe, for example. Aside from this mentioned globe, however, Gan requested minimal decoration unlike previous events. In the morning a siren would sound from a hill south of Moscow. All the factories in town would respond to this call with factory sirens. At this signal, horses, motorcycles and automobiles would lead the masses into the streets from the seventeen Moscow gates, from where they symbolically celebrate the First International in various squares . Then everyone would flock to Red Square, where the Second International is being celebrated together . Then the whole crowd would run to the field of the International , the Chodynka field , where an airfield and a radio telegraph station would be installed. The Third International would develop there as a “socialist structure”.

The central claim of the event was not the decoration, but the participation of the masses, whereby the boundaries between art and life and between participants and spectators are completely removed. This also explains Gan's criticism of Jewreinov's mass action, in which the event took place on a large field in front of the Winter Palace.

Mass action as political theory

While Gan's specifically planned mass actions took the form of festivals, he goes even further in his theoretical writings. Gan writes, “we are already living in and with mass actions. We now have to take up the task of organizing it. ”For Gan, mass action is not just an art form, but a way in which all areas of life are organized. According to some idea, a kind of script, everyone acts more or less in his actions, only these are chaotic and unorganized. This can be translated into a new normative reality through organization. It is not about the establishment of a hierarchical chain of command, but about the careful control of forces in order to generate synergies . Gan's theory of mass action can ultimately also be read as a socio-political theory.

Constructivism (from around 1922)

“Death to art!

It arose naturally

evolved naturally ended up

disappearing naturally.

The Marxists must work in order to scientifically explain their death and to formulate new phenomena of artistic work in the new historical milieu of this time. "

Gan's Marxist art theory, which he formulated in Konstruktiwism , builds on his anarchist phase as a theater and mass action theorist . In terms of the history of ideas, Gan relies next to Marx and Engels in particular on Alexander Bogdanow and partly also on Nikolai Bukharin . Gan's theory of constructivism, as an alternative to art, builds on his earlier concept of twortschestwo , but represents a theoretical refinement of his earlier work and presents it on a Marxist basis.

Goose's theory of art history

He borrowed Gan's theory about the development of art for the most part from Alexander Bogdanow . For Gan, art is a method to strengthen cohesion in a society. The art of primitive society is very uniform, as all people were involved in the work process in common work and their experiences and the worldview that emerges from their work was very similar. With the increasing complexity of society, a difference arose between the people who produce something and those who produce its representation (art, but also worldviews and ideologies). This also resulted in a reversal of the hierarchy of reality and ideology. Ideas and representations (including art) were no longer measured against reality, but against ideology. These representations are identified by society as being of higher value, since people perceive nature as unsystematic and random, and ideology creates order. On the one hand, these ideologies have the ability to connect societies through common values and norms, on the other hand they have the power to cement prevailing privileges. Ideology (and thus also art) were part of the prevention of social progress. The intellectual and material production , however, that the way art is created in Constructivism, the Company holds together also, but this time not true reason than a false ideology, but because of.

A fundamental change is now taking place in capitalism. The findings of the scientific natural sciences reveal the wrong ideologies and begin to disintegrate. Art reacted by no longer being the art of a worldview (such as the Christian art of the Middle Ages) with the function of social cohesion, but becoming an abstract fetishism . It is not about non-representationality , but about separating art from its social function. Bourgeois art sees itself as a value in itself , without the social connection between the work of art and society. In fact, this type of art still contains a social binding function, but loses all positive aspects of it. Gan gives an example of this from Bogdanov. A religious statue, for example, had a binding function in society in its time by connecting believers with one another. If this statue now appears in bourgeois society (for example through an excavation) it no longer has this value, it is viewed according to the genuinely new nappy of abstract fetishism in bourgeois society , with the category of aesthetics . According to Romberg, it is this aesthetic that declares war on Gan and not art in general, as the overly one-dimensional Gan reception has often depicted. This is also made clear by the last sentence in the above indented quote, which is usually not quoted.

Criticism of realism

Interestingly, Bogdanov's line of argument, most of which Gan adopts, has mostly been used to justify realistic art. According to the realists, this would fill the gap between reality and representation through a more precise depiction of reality. Non-representational art (and thus also constructivist art) is, according to the realists, formalism and is only a meta-reflection on problems of art. Gan rejects this criticism by calling realism abstract-illusionistic , while for art he calls for a “real dynamic of concrete movement”. Abstract must be understood here again in the sense of abstract fetishism . Realism only creates a painterly illusion of reality, while constructivism unfolds its real dynamics in life itself. While a painting, even if it is non-representational, is only a static, abstract-illusionistic representation, a “real dynamic of concrete movement” is required by the viewer when viewing a spatial construction. The movement of the objects, the angle of view, the light, the unfolding and dismantling, through these processes what is achieved in spatial constructions is what painting can never achieve. So when Gan demands “The sculpture has to give way to the spatial treatment of the thing. Painting cannot compete with photography, that is, photography ”, then he does not mean to completely eliminate all art, but to use completely new means of artistic expression. Constructivism does not want to fill the gap between art and life, like the realists, by depicting life in art more precisely, but rather to bring art into life. The objects of art are no longer representations of life, but must be used with practical activity.

Tectonics, invoicing and construction

The terms tectonics, billing and construction are central to Soviet constructivism and were demonstrably brought up for the first time by Gan. While construction deals with the structure of the plant, faktura refers to the manufacturing process and tectonics to the social embedding of a plant.

Construction

The term construction existed earlier and was established during the discussions at INChUK on the relationship between composition and construction. In contrast to the composition, the construction is not a rigid, unchangeable relationship between rigid forms designed according to emotional aspects, but the dynamic relationship between these, constructed according to rational rules. The construction can become part of life, the composition only creates visual effects.

faktura

The Russian term faktura is left in the original Russian due to its missing equivalent in the German language. faktura traditionally describes the surface texture of a work, the style of the brushstrokes or the surface treatment of a sculpture. A painting can also be checked for authenticity using the invoice . The term is traditionally associated with individualism and originality. Gan, on the other hand, provides a new definition of the term. For Gan, faktura is the totality of properties of a material or the process of using and shaping these properties by humans.

Gan explains:

“Cast iron is melted, that is, turned into a glowing liquid mass, then poured into a prepared molding box; then it goes through the emery department or is simply roughly cleaned, goes to the mechanical department on the lathes, and only then can you say that the cast iron becomes a thing. This entire process is the invoice, i.e. the processing of the material as a whole, not just the processing of its surface. "

The faktura concept creates a new connection between the person who creates something and the material. The material no longer serves the artist (or better, the constructor ) alone , but rather a "partnership" between the material and its processor. Romberg argues that the constructivists' preference for industrial materials, in addition to the collectivist and proletarian arguments in favor, is also due to the fact that these materials are less passive, cannot be shaped as easily as oil paint or gold, but also because processing demands are made on the processor put. The concept of faktura also makes it clear to what extent Gan criticizes the separation of production and art and thus stands in the tradition of demands for the unity of art and craft, which he only transfers to the new production processes. The definition of faktura as a process (“This entire process is faktura ”) shows that the faktura is not a metaphysical property of the material, but rather the processing by humans shapes the material and forms the central aspect of the concept. This follows the Marxist approach that work is the "basic condition of all human life".

As a result, Gan's focus was much less on the utilitarian necessity of an object. Rodchenko put the usefulness or the целесообразность tzelesoobrasnost (expediency, literally translated "created in relation to a goal") at the center of his work (although it ultimately remained unanswered to what extent his abstract constructions fulfill this usefulness). Rather, Goose's main interest was in the process in which the object is created by humans. For Gan, the created work cannot be separated from his production process, which is an elementary part of the work.

Tectonics

The third central term in Gan's constructivism theory is that of tectonics. Gan's term is conceptually based in part on the term tectology by Alexander Bogdanow . Tectology is a systems theory that aims to unite the various “languages” in the sciences that have been separated since modern times. Tectology was supposed to form a kind of basic language that every science can use and thus the sharp divisions between the sciences are abolished again. A reference to Heinrich Wölfflin , who used the term at the same time but with a different meaning, cannot be ruled out.

For Gan, tectonics describes the social order in which a work of art is located. The work of art is tectonically embedded in a society from which it cannot be separated. The introduction of the term tectonics results from Gans historical-materialistic worldview and in opposition to the ahistorical and eternal values of art in Kandinsky . For Gan, a work of art is inextricably linked with its time and social system. He describes this embedding of the work as tectonics.

The book as a constructivist object

Konstruktiwism , Gan's first book, must not only be seen as a manifesto of his art theory, but must also be understood as a constructivist object. Gan was probably well versed in the printing process and worked directly with the printers. In contrast to the earlier Russian artist books of Futurism , Gan did without elaborate procedures and subsequent manual additions to his books.

reception

During the 1920s, Gan was considered one of the most important representatives of constructivism in Moscow. In an unpublished text for a WChUTEMAS publication from 1922, schoolgirls describe him as the “big fish of constructivism”. At the same time, however, it was seen as its most radical representative, constructivism was only understood in response to its demand for the “death of art”, but hardly as a result of the demands for new artistic means of expression. So it came about that by 1923 all original members of the First Working Group of the Constructivists resigned. However, Konstruktiwism was still able to celebrate a late success when it appeared in various typographic journals in the mid-1920s as an example of new methods of typesetting text.

In Western Europe in particular, Gan was not as well known in the 1920s as, for example, Alexander Rodchenko. This is mainly explained by the sovereignty of interpreting Russian art by El Lissitzky, who was the main mediator between Russia and Germany during this period. Access to information from Russia was difficult, both because of the distance and because of the language, and Lissitzky thus became the authoritative source of information on Russian art for artists in Western Europe, especially his magazine Weschtsch / Objet / Objekt . Lissitzky's lack of mention of Gans presumably has pragmatic reasons; while Rodchenko created various objects that could be easily printed, Gan wrote mainly theoretical treatises at this time.

In Stalinism , Gan's work, like constructivism and the avant-garde as a whole, received little attention. He himself was murdered in the " Stalin Purges ", as was OSA member Mikhail Ochitowitsch . The circumstances of Gan's death were not officially known until 1989. In the same year he was rehabilitated. In the West he received attention earlier, as the presence of his works at the 15th European Art Exhibition in 1977 in Berlin shows. Gan is often mentioned in art history to name the most radical demands of constructivism, whereby his position is usually presented in abbreviated form; a comprehensive review was only possible with Kristin Romberg's monograph from 2010.

Gan's works in the field of graphic design are now exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art in New York .

Publications

editor

- Kino-fot: Schurnal kinematografii i fotografii. [Кино-Фот. Журнал кинематографии и фотографии] (cinema photo. Cinematographic and photographic journal), 6 issues, Moscow, August 1922–1923.

Books and brochures

- День Советской Пропаганды. Лозунги Den Sovetskoi Propagandy. Losungi (The Day of Soviet Propaganda. Slogans). Gosudarstvennoje Isdatelstvo, Moscow 1919. (attributed to authorship)

- Конструктивизм Konstruktiwism (Constructivism), Tverskoe isdatelstwo, Tver 1922.

- Constructivism (excerpts), translated by John Bowlt, in The Tradition of Constructivism, edited by Stephen Bann, Viking Press, New York 1974, pp. 32-42; reprinted in Russian Art of the Avant-Garde: Theory and Criticism, 1902-1934 , edited & translated by John E. Bowlt, The Viking Press, New York 1976, pp. 214-225; reprinted in Art in Theory, 1900–1990: An Anthology of Changing Ideas. Ed .: Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Blackwell 1992, pp. 318-320.

- Constructivism, translated by Annelore Nitschke, into At Zero Point. Positions of the Russian avant-garde. Ed .: B. Groys and A. Hansen-Löve, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2005, pp. 277–365.

- Constructivism. translated and with a foreword by Christina Lodder, Tenov Books, Barcelona 2014 (English).

- Да здравствует демонстрация быта! As sdrawstwuet demonstratzija byta! (Long live the demonstration of daily life!). Goskino, Moscow 1923.

Article (selection)

- К поэтам пролетарских песен K poetam proletarskich pesen. (From the proletarian songs). In: Anarchija 11, (March 1918), p. 2.

- К сотрудникам Пролетарского театра K sotrudnikam Proletarskogo teatra. In: Anarchija 43, (April 1918), p. 4.

- Музей Морозова Musei Morozova . (Morosow Museum) In: Anarchija 45, (April 1918), p. 3.

- Тогда, теперь, и мы Togda, teper, i my. In: Anarchija 47, (April 1918), p. 4.

- Певец рабочего удар Pevets rabochego udar. In: Anarchija 69 (May 1918), p. 4.

- Пролеткульт Proletkult. (Proletkult). In: Anarchija 14 (Mar 1918), p. 4.

- Борьба за 'массовое действо' Borba sa "massowoe deistwo" (The struggle for mass action) In: O teatre . Tverskoe isdatelstwo, Tver 1922, p. 49-80 .

- 1 'ъдемонстрация глупостиь' в устах Люсьена Уоль 1 "demonstratsija gluposti" w ustach Ljusena Uol. In: Srelishcha 60, (October – November 1923), p. 19.

- Борьба за ультиматум Borba sa ultimatum. (The fight for an ultimatum). In: Srelishcha 68, (December 1923 – January 1924), p. 19.

- Кино cinema . (Movie theater). In: Technika i schisn No. 4, 1925, p. 16.

- Факты за нас fact sa nas. (Facts for us). In: Sovremennaya architektura. Jhg. 1 (1926), No. 2, p. 39 ( tehne.com ).

- Что такое конструктивизм? Chto takoe constructivism? (What is constructivism?). In: Sovremenaja architektura 1928, No. 3, p. 79.

- as AG – n: Строящчийся Хабаровск. На стройке дома коммуны Strojashchijsja Khabarovsk. Na stroike doma communy. In: Tichookeanskaja swesda. October 1931.

- The Cinematograph and Cinema. Place and year of first publication unclear. In: Ian Christie, Richard Taylor (Eds.): The Film Factory. Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents 1896-1939 . Routledge, London / New York 1994, pp. 67-68 .

Works (selection)

Mass actions

- May festivities in 1919

- Soviet Propaganda Day (not carried out)

- May festivities 1920 (not carried out)

Graphic design

- Title page (together with Alexander Rodchenko) and layout of Konstruktiwism [Конструктивизм] (Constructivism). Tver: Verlag Twerskoe isdatelstwo, 1922. Print, 22 × 17.4 cm.

- Title page and layout of the magazine Kino-fot: Schurnal kinematografii i fotografii [Кино-Фот. Журнал кинематографии и фотографии] (cinema photo. Cinematic and photographic journal). No. 1-6, 1922-23. High pressure. 29 x 22.2 cm.

- Cover page and layout of the brochure Da sdrawstwuet demonstrazija byta! [Да здравствует демонстрация быта!] (Long live the demonstration of everyday life!), 1923. Print.

- Title page and layout (together with Alexander Rodtschenko) of the magazine Technika i schisn (Technology and Life) No. 1–22, NKPS Transpetschat, Moscow 1925.

- Title page for the magazine Vremya (Time), print, 1924.

- Cover and layout of the magazine SA [CA] (contemporary architecture). No. 1-4, 1926; No. 1-3, 6, 1927; No. 3-6, 1928. Letterpress, 30.5 × 23 cm.

- Poster for the SA's first exhibition, 1927. Print, 107.5 × 72.5 cm.

- Poster for Wystavka rabot Wladimira Mayakowskogo (exhibition of the works of Vladimir Mayakovsky ), 1930. Lithograph, 64.77 × 45.72 cm.

- Title page for Stroitelstwo Moskwy (Moscow's Building Industry, Moscow 1930. Ed. Moscow Workers' Association, No. 10).

- Draft for a title page of Konstruktiwism 2 [Конструктивизм 2] (Konstruktiwism 2). Year unknown.

Product design

- Folding machine for Mosselprom. 1922. (published in Sovremennaja architektura. 1st vol., No. 2, 1926, p. 39.)

- Wserokompom kiosk probably carried out before 1924. (published in Ginzburg, Moisei: Style and Epoch. 1924. The MIT Press, Cambridge, London 1982. Fig. 41–42.)

- Design for a kiosk, 1926. (published in Andrei Novikow: Derewenskii Kiosk. Proyekt - Maket . In: Sowremennaja architektura . 1st century, no. 1 . Moscow 1926, p. 35 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 35.0 MB ]). )

Movies

- The island of young pioneers (The Iceland of the Young Pioneers). Documentation, 1924. (lost, some still images preserved)

- In the Battle for Time and Space (In the Battle for Time and Space; W bor'be sa wremia i prostranstwo), work started in October 1924. It is unclear whether the film was completed. (lost)

Exhibition installation

- First exhibition of the SA, 1927. (Photographs published in Pervaya wystawka SA. Montasch delal Aleksei Gan. In: Sovremennaja architektura . 2nd century, no. 6 , 1927, pp. 159 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 27.0 MB ]). )

Exhibitions during his lifetime (selection)

- May 11, 1924 – June 1924 First discussion exhibition of the associations of active revolutionary artists (Moscow, in an exhibition room of WChUTEMAS)

- April 21–2. May 1925 First exhibition of the film poster (Moscow, on the premises of the State Academy of Art Studies (GAChN), organized by the Academy Film Cabinet)

- 1926 First graphic exhibition (Moscow)

- 1927 First exhibition of modern architecture (Moscow, organized by the OSA)

literature

- Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010 ( Online [PDF; 24.0 MB ] Ph.D. Dissertation).

- А. Н. Лаврентьев (AN Lavrentjew): Алексей Ган (Alexei Gan) . HE Gordejew, Moscow 2010 (Russian).

- Catherine Cooke: Sources of a Radical Mission in the Early Soviet Profession: Aleksei Gan and the Moscow Anarchists . In: Neil Leach (Ed.): Architecture and Revolution: Contemporary Perspectives on Central and Eastern Europe . Routledge, London / New York 1999, ISBN 978-1-134-77164-6 , pp. 13–37 ( Online [PDF; 500 kB ]).

- Kristin Romberg: Labor Demonstrations: Aleksei Gan's "Island of the Young Pioneers", Dziga Vertov's "Kino-Eye", and the Rationalization of Artistic Labor . In: October . tape 145 . MIT Press, 2013, pp. 38-66 , JSTOR : 24586643 .

Web links

- Aleksei Gan on Monoskop.org

- Article on Gan by Ross Wolfe on Charnelhouse.org

- Works by Gan on the MoMA website

Individual evidence

- ↑ Romberg (2010) knows this year of birth through several documents, but there are also individual clues that contradict this. According to Romberg, however, there is no conclusive evidence for the often mentioned year of birth 1893.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010 ( pqdtopen.proquest.com [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 224 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ A b Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 6, 23 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 18, 21 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 23–25 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Malevich claims in his autobiography that several editions were published again in autumn 1919, but no more copies can be found. It is questionable whether this ever appeared or whether it is an error. (cf. Romberg 2010, p. 38)

- ^ A b c Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 38–43 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Kristim Romberg: Gan's Constructivism: Aesthetic Theory for Embedded Modernism at University of California Press, of 2019.

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 44–47 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 50–52 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Simon Karlinsky: Selected Plot Summaries . In: Nancy Van Norman Baer (ed.): Theater in Revolution. Russian Avant-Garde Stage Design 1913–1935 . Thames and Hudson, New York 1991, ISBN 0-500-27646-3 , pp. 190 (Illustrations of Rodchenko's costume designs are printed on pages 12 and 17.).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 100–102 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 113–119 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 176–177 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Denise J. Youngblood: Soviet Cinema in the Silent Era 1918-1935 . University of Texas Press, Austin 1991, ISBN 0-292-77645-4 , pp. 4-8 .

- ↑ Christina Lodder: Promoting Constructivism: Kino-fot and Rodchenko's move into photography . In: History of Photography . tape 24 , no. 4 , 2000, ISSN 0308-7298 , p. 292-299 ( online ).

- ^ A b Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 217, 221–222 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 235 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ A b Charlotte Douglas: Transitional conditions: The first discussion exhibition and the society of easel painters (OST) . In: The great utopia. The Russian avant-garde 1915–1932 . Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 182 .

- ↑ a b c Schirn Kunsthalle (ed.): The great utopia. The Russian avant-garde 1915–1932 . Self-published, Frankfurt am Main 1992, p. 740 .

- ↑ a b c Trends in the Twenties. Catalog for the 15th European Art Exhibition in Berlin 1977 . Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-496-01000-2 .

- ↑ a b Pervaya vystavka SA. Montazh delal Alexsey Gan . In: Sovremennaya arkhitektura . 2nd century, no. 6 , 1927, pp. 159 .

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 31–34 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 77 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ John E. Bowlt: The Construction of Caprice: The Russian Avant-Garde Onstage. In: Nancy Van Norman Baer (ed.): Theater in Revolution. Russian Avant-Garde Stage Design 1913–1935. Thames and Hudson, New York, 1991, p. 73

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 36–37 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 16, 60 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 64–66 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 55–60 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 80–82 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Aleksey Gan: Constructivism. In: Boris Groys, Aage Hansen-Löve (ed.): At zero point. Positions of the Russian avant-garde. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 2005, pp. 298-299.

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 127 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ A b Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 128–130 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 134 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 131–132 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Aleksey Gan: Constructivism . In: Boris Groys, Aage Hansen-Löve (ed.): At zero point. Positions of the Russian avant-garde . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-518-29364-8 , pp. 320 .

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 135 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 137, 140 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Aleksej Gan: The constructivism in: Boris Groys, Aage Hansen-Löve (ed.): At zero point. Positions of the Russian avant-garde . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main, 2005, p. 347.

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 138 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Friedrich Engels: Dialectics of Nature . In: MEW . tape 20 . Dietz, Berlin 1962, p. 444 .

- ↑ Christina Kiaer: Imagine No Possessions. The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism . MIT Press, Cambridge / London 2005, pp. 11 .

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 163 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 164–165 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 215 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ]).

- ↑ a b Trends in the Twenties. 15th European Art Exhibition Berlin 1977 . 3. Edition. Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1977, ISBN 3-496-01000-2 , p. 1/216 .

- ↑ Aleksei Gan. In: moma.org. Retrieved January 15, 2016 .

- ^ Kristin Romberg: Aleksei Gan's Constructivism, 1917–1928 . Columbia University, New York 2010, pp. 195 ( monoskop.org [PDF; 24.0 MB ] The authorship has not been clarified beyond doubt. Other authors only attribute it to Gan or only Rodchenko, but joint authorship seems most likely.).

- ↑ Irina Duksina (ed.): Typeface. Russian avant-garde: [Exhibition in the German Museum of Books and Writing of the German National Library “SchriftBild. Russian avant-garde "] . German National Library, Leipzig / Frankfurt am Main 2015, ISBN 978-3-941113-44-2 .

- ↑ Oksana Bulgakowa (ed.): Kasimir Malewitsch: The white rectangle. Writings on the film . PotemkinPress, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-9804989-2-1 , p. 136 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gan, Alexei Mikhailovich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gan, Aleksei Mikhailovich; Ган, Алексей Михайлович (Russian); Gan, Aleksej Michajlovič |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian graphic artist and art theorist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | uncertain: 1887 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | near Moscow |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 8, 1942 |