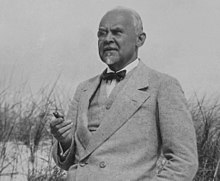

Alfred Grenander

Alfred Frederik Elias Grenander (born June 26, 1863 in Skövde , Sweden , † July 14, 1931 in Berlin ) was a Swedish architect who worked mostly in Berlin. Grenander played a decisive role in the development of Berlin into a cosmopolitan and modern architectural metropolis from 1900.

Life

Alfred Grenander spent his youth in Stockholm , where he began studying architecture at the Stockholm Polytechnic in 1881 . In 1885 he moved to the Technical University of Charlottenburg , where he studied with Johann Eduard Jacobsthal, among others . After completing his studies in 1890, he worked in the Reichstag construction office with Paul Wallot . From then on he was also involved in the planning of the Berlin elevated and underground railway, which opened in 1902.

Grenander initially worked in the architectural offices of Alfred Messel , Wilhelm Martens and Paul Wallot. He then went into business for himself with his brother-in-law Otto Spalding ; the joint architecture firm Spalding and Grenander existed from 1896 to 1903. This was followed by an appointment to the teaching institute of the Berlin Museum of Applied Arts . Grenander's architectural legacy is his design of around 70 elevated and underground railway stations in Berlin. Grenander initially oriented himself towards Art Nouveau , from 1902 to 1931 he preferred the modern style .

Main work: Design of the Berlin subway

Grenander was recruited as an architect by the Hochbahngesellschaft when the Berlin subway opened in 1902 . By 1931 he designed a large part of Berlin's underground stations, which are still largely in their original condition or in an approximate condition after renovations in the meantime.

In his works before the First World War , Art Nouveau influences (decorations on the elevated viaducts) or neoclassical elements (Wittenbergplatz underground station) can often be seen .

At the beginning of the 1920s he could only use plastered wall surfaces as a cost-saving measure, as on the middle section of today's U6.

In his last years, starting in the mid-1920s, he developed a relatively matter-of-fact design language. Major elements of his designs are large, color-fired wall tiles and partly visible heavy, riveted steel supports or supports clad with building ceramics.

The design of the Wittenbergplatz underground station from 1913 is considered his main work. Another impressive building was created in 1926 with the Hermannplatz underground station for the intersection of today's underground lines U7 and U8 with direct access to the Karstadt department store . His largest underground station was built at Alexanderplatz in 1930 with three crossing levels and a distribution floor.

Grenander developed the principle of the identification color , in which each station is clearly distinguished by a color from the stations in front of or behind it. Tiles as well as supports and sign frames can be decorated with the color code. This color code principle can still be partially recognized today on the Berlin underground lines U2 , U5 , U6 and U8 . It was also used by his successors in underground construction until the 1980s.

However, Grenander not only designed subway stations, he was also involved in the design of the subway cars.

More work

After founding the architectural office Spalding & Grenander , Grenander's first own work was some remarkable villas and country houses such as the house built from 1894-95 at Potsdamer Straße 22a in Berlin-Lichterfelde (together with Spalding). Grenander later designed buildings for Knorr-Bremse AG at the two locations near the Ostkreuz (Neue Bahnhofstrasse and Hirschberger Strasse) and Ludwig Loewe & Co. in Moabit (1908 and 1916). Bridges were also designed by him, such as the Gotzkowsky Bridge in Moabit (1911) and the Schönfließer Bridge. In 1906 and 1907 Grenander had an English country house or summer house , the Villa Tångvallen, built in Falsterbo in the style of the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau movement. He also built the Solglimt villas for his mother-in-law Karoline Åwall and the so-called Wertheimshuset for the Ipsen family in the southern Swedish coastal town . He worked as a furniture designer for the 1904 World's Fair , when he designed an Art Nouveau living room ensemble. He designed other furniture for the KPM showroom at the Dresden arts and crafts exhibition in 1906 and for his private villa in southern Sweden. In Neu-Kladow he designed the interior of the manor house there.

In 1910/11 he built the Villa Herpich, which still exists today, in Potsdam-Babelsberg for department store owner Paul Herpich . Today it is known as the Stalin Villa , as Josef Stalin resided there in 1945 during the Potsdam Conference . In 1920 he converted a former farmstead in Alt-Schmöckwitz , the Landhaus Reich, into a country house complex with a round arched wall. The Swedish Church designed by Grenander was built in Berlin from 1920 to 1922, and from 1923 to 1923 the Swedish cemetery followed on the south-west cemetery in Stahnsdorf .

Commemoration

The German Museum of Technology showed from November 2006 to August 2007 a special exhibition on the oeuvre of Alfred Grenander. This exhibition then moved to Stockholm, where it was on view in the local architecture museum until January 6, 2008.

On June 6, 2009, the previously unnamed square in front of the entrance area of the Krumme Lanke underground station he designed was given the name Alfred-Grenander-Platz .

The former BVG administration building he built and is now a listed building at Rosa-Luxemburg-Strasse 2, at the corner of Dircksenstrasse 35, is now called Grenander-Haus .

On the occasion of his 150th birthday, the BVG honored him with a “Grenander year” and erected a “Grenander memorial stele” in the shopping arcade of the Alexanderplatz underground station .

literature

- Martin Richard Möbius (introduction): Alfred Grenander. (= Neue Werkkunst . ) Friedrich Ernst Hübsch Verlag, Berlin 1930. ( as a reprint with an afterword by Bettina Güldner: Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7861-2283-0 .)

- Irmgard Wirth: Grenander, Alfred Frederik Elias. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , p. 46 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Heiko Schützler: A masterful modernist. The architect Alfred Grenander (1863–1931) . In: Berlin monthly magazine ( Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein ) . Issue 7, 2001, ISSN 0944-5560 , p. 103-113 ( luise-berlin.de ).

- Christoph Brachmann: Light and color in the Berlin underground. Classic modern subway stations. Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-7861-2477-9 .

- Aris Fioretos (ed.): Berlin above and below ground. Alfred Grenander, the subway and the culture of the metropolis. Nicolaische Verlagsbuchhandlung, Berlin 2006, ISBN 3-89479-344-9 .

- Christoph Brachmann, Thomas Steigenberger (Ed.): A Swede in Berlin. The architect and designer Alfred Grenander and Berlin architecture (1890–1914). Didymos-Verlag, Korb 2010, ISBN 978-3-939020-81-3 .

- Nikolaus Bernau: More than the subway architect. In: Berliner Zeitung of June 23, 2010 ( berliner-zeitung.de ).

Web links

- Literature by and about Alfred Grenander in the catalog of the German National Library

- Alfred Grenander. In: arch INFORM .

- Biography and overview of works on the website of the Berlin U-Bahn archive

- Alfred Grenander's oeuvre in the context of Berlin's architectural history , project of the TU Berlin

- “The work of the architect Alfred Grenander” ( Memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ), Museum Journal, October 2006, pp. 72–73

supporting documents

- ↑ Bernhard Schulz: Design and technology belong together. In: Der Tagesspiegel . November 16, 2006 ( tagesspiegel.de ).

- ↑ Knorr-Bremse A.-G., Berlin-Lichtenberg, administration building and factory in Bahnhofstrasse, built by the architect Alfred Grenander in Berlin, 1913–1916. In: Journal of Construction . Volume 74 (1924), Hochbauteil, pp. 78-102 ( digital copy in the holdings of the Central and State Library Berlin ).

- ↑ Axel Mauruszat: Alfred Grenander: Schönfließer Bridge. In: U-Bahn Archive. Retrieved February 20, 2011 .

- ↑ Arkitekten Grenaders exklusiva Prylar säljs | Kvällsposten. Retrieved September 9, 2019 (Swedish).

- ↑ Alex, he Vickhoff alex: Stjärnarkitektens lyxhus i Falserbo förfaller. Retrieved September 9, 2019 (Swedish).

- ^ The Berlin U-Bahn Archive - Alfred Grenander. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ^ A b c Institute for Art History and Historical Urbanism: A Swede in Berlin: The oeuvre of Alfred Grenander in the context of Berlin's architectural history (1892-1930). Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ↑ En vandring genom tid och rum. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Skanörgårdarnas historia skriven. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Louise full Ercolino: Han byggde tunnelbanan i Berlin. Trelleborgs Allehanda , December 13, 2007, accessed September 9, 2019 (Swedish).

- ^ Ingemar H. Johansson: Wertheims och Anna Ipsen. Kulturföreningen Calluna - Då och Nu på Ljungen, December 2008, accessed on September 9, 2019 (Swedish).

- ↑ This living room is a real treasure. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ^ Alfred Grenander, furniture ensemble for the St. Louis World Exhibition, 1904 - Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ^ Jürgen Wetzel: Berlin in the past and present . In: Landesarchiv Berlin (Ed.): Yearbook of the Landesarchiv Berlin 2003 . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2003, p. 45 ( google.de ).

- ↑ En doldis i världsklass bjuder på international interest in Helsingborg's auction sale. April 27, 2014, accessed September 9, 2019 (Swedish).

- ↑ Gutspark Neukladow. June 11, 2019, accessed September 9, 2019 .

- ^ Katrin Lange: The return of the artist. March 7, 2012, accessed on September 9, 2019 (German).

- ^ German biography: Grenander, Alfred - German biography. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ↑ a b Martin Klesmann: Lothar Bisky later worked where Stalin resided. The Soviet dictator lived in the Villa Herpich during the Potsdam Conference in 1945 . In: Berliner Zeitung . July 18, 2005 ( berliner-zeitung.de ).

- ^ List, map, database / Landesdenkmalamt Berlin. Retrieved September 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Arkitekturmuseet: Berlin under och över jorden. Archived from the original ; accessed on September 5, 2018 .

- ↑ Bahn Berlin Info: Berlin gets a Alfred Grenander Square.

- ^ Monuments in Berlin - BVB administration. In: Denkmaldatenbank Berlin, accessed on July 19, 2013.

- ↑ Grenander House. In: arch INFORM ; Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- ↑ Entry in the Berlin State Monument List with further information

- ↑ News in brief - U-Bahn . In: Berliner Verkehrsblätter . No. 10 , 2013, p. 198 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Grenander, Alfred |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Grenander, Alfred Frederik Elias (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Swedish architect |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 26, 1863 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Skovde , Sweden |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 14, 1931 |

| Place of death | Berlin |