Labor Movement in the United States

Organized associations for the defense and improvement of workers' rights in the USA are summarized under the labor movement in the United States .

history

The situation of the workers in the British colonies

About half the population in the North American British colonies were employed by 1750. In contrast to Europe, the social situation of the workers was quite heterogeneous, which was an obstacle to a union of workers with the aim of improving their situation. The employees can be divided into two large groups: the first consists of those male whites who were shipped from the Anglo-Saxon motherland to the colonies as convicts, forced laborers or debtors , but who became free citizens after completing the work imposed on them , and the second from those without rights Slaves . A telling picture is the breakdown of the population of Carolina in 1708: of around 9,580 inhabitants (including around 1,400 indigenous peoples ) around 4,100 were slaves .

The comparatively good wages of the workers of the first group, resulting from a shortage of workers, resulted in little interest in such workers' associations. A worker in New England at the time was making three times as much as his peers in England and even six times as much as a worker in Sweden or Denmark. In addition, the Irish in the colonies (and only there, as far as the British Empire was concerned) were legally and politically equal to other “whites”. The working immigrant had apparently gained sufficient economic, political and legal freedom in his new home. In addition, the existence of a large number of opportunities for advancement, which were open to the workers of the first group, could not lead to a permanent, economically conditioned fraternization .

Early craftsmen's associations and initial demands

These conditions only changed - albeit tentatively - at the end of the colonization period and in the early days of the United States. At that time the USA was democratically constituted, but still a society of estates, at the head of which was a group of successful merchants and planters. Its members were solely free to found political and social institutions, as this right was only granted to the self-employed.

For the majority of employees, slavery and forced labor were part of their living environment, and they were also prohibited from joining forces for the purpose of joint action. The first demands were already articulated in the transition period from mercantilism to capitalism 1760–1830: the first strike took place in 1763 in Charleston , South Carolina - an action by free Afro-American chimney sweeps.

The War of Independence demanded the cohesion of the people who supported independence, regardless of the social status of each individual. According to John Adams , only a third of the population favored breaking with Britain. During the war, local workers' organizations emerged, which are considered the forerunners of trade unions , trade organizations and political groups. These so-called “mutual aid associations” or “boxing clubs” took on new immigrants and provided help in the event of illness and death. They were structured according to professions, e.g. B. the New York "Friendly Society of Tradesmen and House Carpenters" founded in 1767. Another example is the "Marine Society", which was founded in 1756, but was dissolved after a strike by 150 of its members in 1779 and reunited in the "Sons of Neptune".

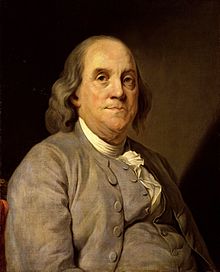

The Constitutional Fathers didn't think much of workers. Benjamin Franklin said this about the workforce in 1768:

“Saint Monday is as duly kept by our working people as Sunday; the only difference is that instead of employing their time cheaply at church they are wasting it expensivly at the ale house. "

“ Blue Monday is just as conscientiously observed by our workers as Sunday; the only difference is that instead of spending their time cheaply in church, they waste it dearly in the pub. "

The rights granted in the course of the Declaration of Independence and the Revolution , such as the right of assembly and petition , freedom of the press , the right to due process and the right to vote for all men considered "white" sparked republican enthusiasm among workers and peasants. However, not long after the United States was recognized by the United States, the first organized work stoppages in American history took place: in Philadelphia, which is traditionally industrial, the shoemaker and printer formed unions to strike in 1785 and 1786. At the same time, the "Mechanical Society" was formed in Baltimore.

Thomas Jefferson's " Land Ordinance " of 1785 and the " Northwest Ordinance " of 1787 made inexpensive land available, together with an education offensive they took away the workers' displeasure. While the peoples of Europe only seemed to be left with the struggle for self-liberation in order to avoid impoverishment, the Americans were able to turn to the west with the children and cones in the face of impoverishment, in order to build a new life there, while the state as such became increasingly anti-worker and anti-union . In contrast to many European countries - above all Russia, but also Central Europe - the American economy was no longer purely agricultural at this point, but in some cases already pre-industrial.

The effects of industrialization

In the United States, too, the situation of workers changed dramatically with industrialization . The change in market structures and the onset of industrialization is called the market revolution in the USA . Part of the radical social changes that accompanied industrialization was the creation of a new class, the proletariat . In the USA, too, there was a concentration of economic capital in favor of a small segment of the population. Without adequate social and legal protection, American workers in the Gilded Age not only found themselves at the mercy of the employers, but also came under psychological pressure and ran the risk of losing their self-esteem.

Because of its duration, the industrial revolution in the United States can also be referred to as an industrial revolution. Around 1789, 21-year-old Samuel Slater brought with him plans for the “ Spinning Jenny ” developed in Great Britain , a loom that revolutionized the textile industry. Eli Whitney developed a cotton gin in 1793, as a result of which the process of industrialization accelerated. Favored by the wars in Europe, the mass production of rifles and shotguns began in 1798 . The policy of isolationism led to an intensification of American self-sufficiency efforts: in 1810 there were 87 textile factories in Pennsylvania, in which around 500 men and over 3,500 women and children were employed. A situation that Alexander Hamilton did not regret but welcomed during his lifetime: "Women and children make themselves more useful, and the latter useful earlier, if they work in factories." The second War of Independence from 1812 to 1814 caused a renewed stimulation of the economy the mutual embargo between Great Britain and the USA. Shipping and ammunition factories in particular were expanded: while only 55,000 t of iron were produced in the USA in 1810, it was 180,000 t in 1830. Even more manpower was needed to develop the hinterland and canal link between New York and Chicago, two projects made possible by large government investments. These developments were accompanied by a population explosion: from 1790 to 1820 the US population had increased from 4 to 10 million, in 1840 there were 17 million people in the US and at the beginning of the civil war there were 31.5 million.

The American economy can be divided into two epochs for the period up to the Civil War: from 1815 to 1843 one can speak of a pre-industrial society in which most of the products were manufactured by hand. From 1843 one can speak of an industrial transformation.

However, the boom came to an end together with the British-American War and the subsequent lifting of the embargo policy: American products were unable to compete with cheap British products, so that the first economic crisis occurred in 1819 .

Trade unions, parties and workers' organizations

The ensuing economic crisis and the resulting impoverishment of the workforce produced a relevant trade union movement in the USA. In 1824 there were organized work stoppages again for the first time, in Samuel Slater's textile factory. In the following year, a serious union was formed: the “ United Tailoresses of New York ”. Political demands were quickly added to the job-related ones. Since workers' rights were restricted at the federal and state levels, this step seems logical once organized structures are in place. A class consciousness that had arisen in the Philadelphia Mechanics Union of Trade Associations , which was reflected in its program, which stated that workers create wealth but not participate in it and demand political power, resulted in the founding of the Workingmen's Party “1828 and a sister organization in New York in 1829. She first called for a fair distribution of wealth through inheritance tax , the socialization of banks and factories and the ban on land ownership. In the further process, these demands were expanded: Thus a free and public education system (according to an estimate there were 1,250,000 non-literate children in the United States in 1834), the abolition of imprisonment for debtors, a lien to secure wages, a fairer tax system , called for the participation of non-owners in public offices and the abolition of compulsory service in the militia . As early as 1832, the Association of the Working People in New Castle demanded the right to vote for women . Initially, however, most male workers were also excluded from voting, which only changed with the era of the " Jeffersonian Democracy " and the " Jacksonian Democracy ". The Workingmen's Parties - which were largely constituted locally - reached the high point of their existence in the late 1820s / early 1830s. America's first Labor Party was founded in Philadelphia in the summer of 1828, and from there the movement spread westward to Pittsburgh , Lancaster , Carlisle , Harrisburg , Cincinnati, and other cities in the states of Ohio and Pennsylvania . It penetrated to Delaware to the south and to New York , Newark , Trenton , Albany , Buffalo , Syracuse , Troy , Utica , Boston , Providence , Portland and Burlington to the north . Between 1828 and 1834 workingmen's parties took place in 61 cities - in places where none were formed, their function was performed by craft associations. After the city council elections in Philadelphia in 1829, the Labor Party there had 20 MPs, its New York sister defended the 10-hour day in the public service, while like-minded parties celebrated electoral successes in Albany, Troy and Salina in 1830 . At that time, 20 workers' newspapers appeared, mostly in New England and the Mid-Atlantic states, such as the “ Workingmen's Free Press ” founded in 1827 , the organ of the “Mechanic's Union of Trade Associations” together with the Workingmen's Party.

The Workingmen's Parties, however, fell apart at the height of their power; mainly from internal quarrels; In addition, the state and the two established parties quickly took up workers 'demands, which they also represented externally through their own internal workers' organizations. In 1834, the working class wing of the Democrats had become so strong that they were decisive for the first general mayoral election in New York and helped Cornelius Van Wyck Lawrence into office. Even more important was Andrew Jackson's victory in the presidential election two years earlier: with his criticism of capitalism and attacks on the central bank, he had secured the votes of those who were critical of industrialization, and with their help had moved into the White House. The same was true of the Republicans. The Republican Richard Yates said in 1860: “The great idea and basis of the Republican party, as I understand it, is free labor. [...] To make labor honorable is the object and aim of the Republican Party. ”The Republican Party glorified work and the worker out of a Protestant ethos . The Protestant ethos also paved the workers' way into the bourgeois parties, because their movement arose less from the ideas of Marx and Engels than from this Protestantism. These successes and the above-mentioned acceptance of numerous workers 'demands made the existence of independent workers' organizations obsolete. In addition, the recovery of the economy at the beginning of the 1830s and the large territorial land gains made by the USA significantly improved the living conditions of most workers, who thus devoted themselves to personal and company-internal goals, so that they disappeared from the political scene as an independent force after a brief flowering.

At the same time it was a little different with the trade unions: Since their demands and movements were mainly of a business and not political nature, they were able to hold out longer. In 1836, 300,000 American workers were unionized (compared to 26,500 in 1833) - a percentage that was not reached again until the New Deal era - and mainly fought for the legalization of workers' actions, which were still penalized by the conspiracy , and the 10-hour day. 150 unions had sprung up in the New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore areas alone - and they were not confined to the Atlantic coast, including in Buffalo, St. Louis, Pittsburg, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Louisville and other parts of the country that continued to grow Frontier were moved ever closer to the center of the nation, employee representatives were founded. In the same time frame - from 1834 to 1838 - the aforementioned large canal construction project was carried out. The workers here were not highly organized, but there were still work stoppages and strikes, which were bloodily suppressed by federal troops for the first time in 1834 . In the industrial sector, an example from Philadelphia set an example, where ten unions joined together in 1833 and successfully advocated the 10-hour day. A follow-up strike in Boston failed, however, but was tried again two years later: Following an idea by the labor leader William Benbow , 20,000 TUCCP (" Traders Union of the City and County of Philadelphia ") workers stopped work and won the day - they triggered a wave that spread to all American industrial cities.

Examples

It is difficult to speak of a unified American labor movement, as it developed out of a non-homogeneous work landscape in which there were sometimes serious differences in the same sector. This is most strikingly evident in the cities of Lowell , Massachusetts and Manayunk, Pennsylvania.

Lowell

The city of Lowell, built up as a purely industrial center, is a positive example . The town, which had just 200 inhabitants in the early 1820s, was systematically expanded and thirty years later already had 33,000. None of the investors, mainly business people from the west coast, settled in Lowell themselves - however, they created liberating conditions for the "Lowell mill girls", single farmer daughters from the area, who were independent of working in the factory until they were married worked at home and were housed in the company's own dormitories. They earned 40 to 80 cents a day, their male colleagues (guards, overseers, mechanics) 85 ¢ - 2 $ / day.

A Lowell worker described her work in a letter dated 1840 as follows:

“[...] In the mills, we are not so far from God and nature, as many persons might suppose. We cultivate and enjoy much pleasure in cultivating flowers and plants. A large and beautiful variety of plants is placed around the walls of the rooms, giving them more the appearance of a flower garden than a workshop. [...]

Another great source of pleasure is, that by becoming operatives, we are often enabled to assist aged parents who have become too infirm to provide for themselves; or perhaps to educate some orphan brother or sister, and fit them for future usefulness. And is there no pleasure in all this? no pleasure in relieving the distressed and removing their heavy burdens? [...]

Another source is found in the fact of our being acquainted with some person or persons that reside in almost every part of the country. An through these we become familiar with some incidents that interest and amuse us wherever we journey; and cause us to feel a greater interest in the scenery, inasmuch as there are gathered associations about every pleasant town, and almost every house and tree that may meet our view.

Let no one suppose that the "factory girls" are without guardian. We are placed in the care of overseers who feel under moral obligations to look after our interests; and, if we are sick, to acquaint themselves with our situation and wants; and, if need be, to remove us to the hospital, where we are sure to have the best attendance, provided by the benevolence of our agents and superintendents.

In Lowell, we enjoy abundant means of information, especially in the way of public lectures. The time of lecturing is appointed to suit the convenience of the operatives; and sad indeed would be the picture of our Lyceums, Institutes, and scientific Lecture rooms, if all the operatives should send themselfs.

And last, though not least, is the pleasure of being associated with the institutions of religion, and thereby availing ourselves of the Library, Bible Class, Sabbath School, and all other means of religious instruction. […]. "

“[…] Here we are not as far from God and nature as many people might think. We experience and enjoy growing flowers and plants. A great and wonderful number of plants are around the walls of the rooms, which make them look more like a flower garden than a workshop. […] Another great joy is that we, who have become workers, are able to help our aged parents, who have become too frail to take care of themselves; or possibly teaching an orphaned brother or sister and preparing them for future usefulness. And is there no joy in it? No joy in relieving the distress of the troubled and relieving them of their heavy burden? […] Another source is getting to know people from all over the country. And through this we become acquainted with events that interest us and look forward to wherever we go; and they guide us to show a greater interest in the landscape than to collect joyful impressions of every city, and of almost every house and tree that crosses our gaze. But don't make anyone think that the "factory girls" are without guardians. We are placed in the care of overseers who see it as their moral obligation to defend our interests; inquire about our situation and our wishes when we are sick and, if necessary, take us to the hospital, where, thanks to the generosity of our overseers and guardians, we can be sure of receiving the best possible assistance. At Lowell we have ample opportunities to educate ourselves, especially in public lectures. They take place when the workers can visit them; it would be too sad if all the workers stayed away from our lyceums and institutes and lecture halls. And last but not least, we have the pleasure of connecting with religious institutions so that we have the library, Bible class and Sunday school, and other other religious institutions at our disposal. [...]. "

When the first strikes broke out in 1834, as wages were reduced by 15% due to falling profits and there was an actual wage cut of 12.5% in 1836 due to increased costs for board and lodging, the well-off Loweller workers met with incomprehension from their colleagues elsewhere . 1,500 young women went on an unsuccessful strike. Nonetheless, the establishment of a union for these women was welcomed and supported by the Philadelphia Journeymen Cigar Makers as a step in the right direction.

Another big difference to the Manayunk example below is the ethnic composition of the female workers: in 1836 only 4% of all female workers were immigrants (this changed drastically until 1860, when it was over 60%).

Manayunk

Manayunk was called the "Manchester of America" because of its enormous textile industry - at the beginning of the 1830s there were eight large factories here. Statistics are only available from 1837: at that time, children up to nine years of age worked here for 75 ¢ / two weeks, children from 9 for ½ to 1 $ / week, women for 2 $ and men for 7.50 $ / week for one 13 hour day. Women were deducted half of their wages for accommodation, meals and heating costs (it must be said that the significantly higher wages for men can also be explained by the fact that they were provided with family support, while women - often single unmarried girls and housed in dormitories - at least according to the wage planning, they only had to pay for themselves.) In addition, up to half of the due wages were withheld on the monthly payday. A huge difference to the conditions in the Lowell described above.

These conditions sparked a wave in the early 1830s, when they were likely to be worse, that managed to spill over to the federal level. Much of the workforce was European immigrants, inspired by the introduction of the ten-hour day in European Great Britain, while in the same year two of the Manayunker plants introduced a 20 percent wage cut. This led to a strike, mainly carried out by women, which was then organized in November of the same year under the umbrella of the TUCCP. It lasted until May 1834, when the strikers were granted a 5% wage increase (which still meant a wage cut from the original wage). One of the leading figures in the industrial action, John Ferral, who immigrated from Ireland, founded the first nationwide workers' organization in New York in 1835 with representatives of other unions from Boston, Poughkeepsie, Newark and New York: the " National Traders Union ", which he chaired in Philadelphia conducted the first general strike in US history for the general 10-hour day and prevailed in this city. News of this success spread like wildfire and found imitators in the states of New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Maryland, and South Carolina. Most were crowned with success, so that by the end of 1835 most skilled craftsmen had a normal working day of ten hours, two hours less than before. The working hours of ordinary workers also fell.

Further development up to the civil war

In 1842, after the great days of the trade unions were practically over, they were legalized by court order in the USA - strikes, however, still fell under the criminal offense of conspiracy. The organized workforce had once again been taken out of their sails, and although the renewed economic crisis that began in 1837 would suggest a new start, the structure of the workforce had changed considerably: in the 1840s, 3 million people immigrated to the USA, mainly Irish and Germans (who together made up 70% of the immigrants), followed by Scots, Norwegians and English, among them also many political refugees, at the latest after the failed revolutionary year of 1848 , those without a family in the United States to support them would be at the mercy of total poverty without a job and accept any job on any condition. In 1847 there were 100 immigrants for every 10,000 inhabitants, which is proportionally the highest immigration rate in US history. This policy of wage dumping divided the workforce and led to “racial conflicts” between locals and immigrants among the unemployed. The last major unrest occurred in 1842 during the struggle for universal suffrage (at least for men), during which revolutionary riots broke out in Rhode Island and were crushed by government forces. However, the right to vote was granted. Since white workers now had local voting rights in almost all states, they were further involved by the major parties. In the same year, the general 10-hour day was fought for in New Hampshire (however, employers circumvented this rule by immediately firing all workers and only reinstating those who had contracted “voluntarily” overtime). Similar regulations were introduced in Pennsylvania in 1848 until they later became neat and the practice of "voluntary" overtime was banned. In 1842 a new economic growth set in, the rapid US expansion from 1844 to 1860 finally completely diverted from the immigration problems. Jobs created ensured social peace, the war against Mexico and the gold rush distracted attention from social problems. In 1861 the American Civil War broke out.

literature

- Benita Eisler (Ed.): The Lowell Offering. Writings by New England Mill Woman (1840-1845) , New York a. a. 1977.

- Eric Foner: Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men. The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War , Oxford u. a. 1970.

- Philip S. Foner: The American Labor Movement from the Colonial Era to 1945 , Berlin / GDR 1990.

- Herbert G. Gutman: Work, Culture & Society in Industrializing America , 4th Edition, New York 1976.

- Jürgen Heideking: History of the USA, 3rd edition, Tübingen / Basel 2003.

- Philip Yale Nicholson: History of the Labor Movement in the USA , Berlin 2006.

- Karl Heinz Röder (ed.): The political system of the USA. Past and present , 3rd edition, Berlin / GDR 1987.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 35.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 38.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 36.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 50.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, pp. 47–50.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 49.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 53.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ a b c Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 54.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 55.

- ^ A b Gutman, Herbert G .: Work, Culture & Society in Industrializing America, 4th edition, New York 1976, p. 5.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 58.

- ↑ a b c Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 61.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, pp. 62 and 73.

- ↑ a b Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 65.

- ^ Heideking, Jürgen: Geschichte der USA, 3rd edition, Tübingen / Basel 2003, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ a b Heideking, Jürgen: Geschichte der USA, 3rd edition, Tübingen / Basel 2003, p. 217.

- ↑ a b c Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 73.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 68.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 69.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ a b Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 72.

- ^ Heideking, Jürgen: Geschichte der USA, 3rd edition, Tübingen / Basel 2003, p. 112.

- ^ A b Gutman, Herbert G .: Work, Culture & Society in Industrializing America, 4th edition, New York 1976, p. 13.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA. Berlin 2006, pp. 71-73.

- ↑ a b Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 75.

- ↑ a b c d e Foner, Eric: Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men. The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War, Oxford a. a. 1970, p. 18.

- ^ A b Foner, Eric: Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men. The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War, Oxford a. a. 1970, p. 16.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 76.

- ↑ a b Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA. Berlin 2006, pp. 77, 79.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA. Berlin 2006, pp. 92, 93.

- ↑ Jürgen Heideking: History of the USA. 3rd edition, Tübingen / Basel 2003, p. 141.

- ^ A b c Foner, Eric: Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men. The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War, Oxford et al. 1970, p. 11.

- ↑ Foner, Eric: Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men. The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War, Oxford et al. a. 1970, pp. 11-18.

- ^ Gutman, Herbert G .: Work, Culture & Society in Industrializing America, 4th Edition, New York 1976, p. 3.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 82.

- ↑ a b Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 93.

- ↑ a b c Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the labor movement in the USA. Berlin 2006, p. 90.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Heideking, Jürgen: Geschichte der USA, 3rd edition, Tübingen / Basel 2003, p. 119.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 92.

- ↑ Quoted from: Eisler, Benita (Ed.): The Lowell Offering. Writings by New England Mill Woman (1840 - 1845), New York et al. 1977, p. 64 f.

- ^ A b Foner, Philip S .: The American Labor Movement from the Colonial Era to 1945, Berlin / GDR 1990, p. 12.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 101.

- ↑ a b c Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 88.

- ↑ a b c Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 89.

- ↑ Foner, Philip S .: The American Labor Movement from the Colonial Era to 1945, Berlin / GDR 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ a b c Foner, Philip S .: The American Labor Movement from the Colonial Era to 1945, Berlin / GDR 1990, p. 15.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 96.

- ↑ a b Heideking, Jürgen: Geschichte der USA, 3rd edition, Tübingen / Basel 2003, p. 113.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, pp. 102-103.

- ↑ a b c Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 97.

- ↑ a b Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 100.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 103.

- ↑ Nicholson, Philip Yale: History of the Labor Movement in the USA, Berlin 2006, p. 104.