Asymmetrical warfare

An asymmetrical war is a military conflict between parties that are very different in terms of weapons technology, organization and strategy . Because asymmetrical warfare differs from the usual image of war, the term asymmetrical conflict is also used.

Typically, one of the warring parties involved is so superior in terms of weapons and numbers that the other warring party cannot win militarily in open battles. In the long term, however, pin-prick-like losses and attrition from repeated minor attacks can lead to the withdrawal of the superior party, also due to the overstretching of their forces. In most cases the militarily superior party, usually the regular military of one state, acts on the territory of another country and fights against a militant resistance or underground movement that has emerged from the local population. This form of warfare is therefore also referred to as guerrilla warfare (s) in older literature . The supposedly superior war party is therefore not familiar with the area of operation and its population and will only ever be able to apply its forces selectively in the extensive area of operation. In addition, it often finds itself in an inferior position ideologically and for this reason cannot win the fight. The apparently inferior side, however, is mostly recruited from the regional population and is supported by them with information and logistical support.

Both the phenomenon itself and the military-theoretical foundations have been known since ancient times. Examples from the 20th century are the colonial wars , in which national liberation movements in colonies violently attacked the respective colonial powers and their military (see also guerrillas ). Since around the end of the Cold War in 1990, the term has also appeared as unconventional warfare , which was previously mainly known to experts, increasingly in public debates, increasingly in connection with the occupation of Iraq 2003-2011 and the NATO mission in Afghanistan ( ISAF ) .

Military approaches for combating ground - or resistance movements by regular military are also referred to as counter-insurgency (Engl. Counterinsurgency or COIN summarized). Because such conflicts often last for years without causing major fighting, they are also called conflicts of low intensity designated (Engl. Low Intensity Conflict).

Concept history

The term “asymmetrical warfare” became known to the public when, after the end of the Cold War, classic (“symmetrical”) wars between states determined the threat scenarios in many countries to a much lesser extent than modern guerrilla warfare . In general, terrorism and acts of war in an undeclared war between two warring parties, one of which is inferior in conventional strength, are often used synonymously, but they must be separated from one another.

The organized use of force in modern terrorism was also recorded as war with the formation of the term “asymmetrical warfare” , although it differs greatly from the classic armed conflict of the past centuries. In particular, the hegemonic position of the USA as the only remaining superpower is understood as "asymmetrical out of strength", while terrorism out of weakness resorts to unorthodox methods of combat and combat. In this sense, terrorism appears as a further development of partisan warfare, with which, since its inception, the Spanish guerrillas have defended themselves against the Napoleonic occupation by those who would have been defeated in an open battle. It is essential for the characterization that a conventional army that does not win a war loses, whereas a guerrilla wins in an asymmetrical war if it does not lose it.

The concept of partisans (of Italian partigiano partisans;. Cf. Party ) as an armed fighter, not to the regular armed forces of a state belongs is used interchangeably in this context, but usually in an irregular fighters in connection with the conventional wars of the 20th. Century as related to the Soviet partisans , the Resistance France or the " Forest Brothers " in the Baltic States .

The concept of asymmetrical warfare was dealt with early in military theory and during the colonial conquests and the subsequent wars of the regional population against the colonial troops in South Africa, Namibia, formerly German South West Africa, Tanzania with Rwanda and Burundi, formerly German East Africa, and in China applied.

Johann von Ewald published his "Treatise on the Little War" in Kassel as early as 1785, which was based on his experiences with the insurgents in the North American colonies and those of the Americans during the Seven Years' War in North America (in particular through the use of light troops under Robert Rogers ) was based.

In his book Vom Kriege, Carl von Clausewitz also describes the concept of asymmetrical warfare in the chapter on people's armament and, in Vom kleine Kriege , carries out combat actions under these special conditions.

This type of warfare was also made famous by Thomas Edward Lawrence , known as Lawrence of Arabia , during the First World War in Arabia, who used the military tactics of hit and run by permanently deep flanking attacks on the supply and transport lines of the Turkish army Ottoman Empire like the Hejaz Railway and against the Ottoman Military Railway in Palestine and interrupted it. He was able to successfully conquer the city of Aqaba over the land side of the Nefud desert as a supply point for the British army.

Mao Zedong systematized this warfare in the 1920s and 1930s and based it on the ancient writer Sun Tsu , who 510 BC. Wrote a book on the thirteen principles of warfare. The aim of his strategy was the consistent evaluation of errors and weaknesses of the enemy while using small units or individuals operating out of the element of surprise. According to Sun-Tsu, the strategy was to be determined by the means available. The aim was to hit the enemy with inferior means and consistently apply this concept and finally to beat them. One advantage of asymmetric warfare is its low cost. A guerrilla force is able to fight a well-armed enemy with primitive weapons, some of which have been taken from the enemy. To protect his supply lines and objects worth protecting, the enemy has to make a great effort, which causes high costs.

Examples of asymmetric warfare include the Burma campaign by the British and American armies in 1944, the French Indochina and American Vietnam wars, most wars and wars of independence in Africa, the Russian Afghan war 1979/1989, the American war in Afghanistan since 2001 (2001 / 2009) and the 2003 Iraq war in the United States, the wars of Russia in Chechnya or the Palestinian Intifada , the civil wars caused by partly communist movements in Central and South America, such as the FARC in Colombia, and as one of the last asymmetrical clashes in Mali the Opération Serval .

The term asymmetric warfare was first used in the post-Soviet era (in military circles as early as the 1960s) in connection with Operation Allied Force and the warfare of the Yugoslav People's Army in 1999. After the war, it was found that NATO's air strikes had little effect and that the Yugoslav People's Army was only slightly hampered in the war against the UÇK (Kosovar Liberation Army). The reason for this was the concept of distribution, camouflage, cover and the surprising direct attack on the enemy using the knowledge of the terrain by the Yugoslav army.

The same logic underlies terrorist activity. A terrorist attack like that of September 11, 2001 cost the terrorists very little compared to the large investments in security at the airports that resulted from it.

The most important theoretician of this warfare in the second half of the 20th century was the Brazilian Carlos Marighella . His Mini-manual do Guerrilheiro Urbano (literally: Mini-Handbuch des Stadtguerillero , in German version mostly translated as a manual of the urban guerrilla ), São Paulo 1969, was mainly adapted by Western European terrorist groups such as the RAF .

The asymmetry of the battle also took place in each of the colonial wars, since the liberation movements or guerrillas were mostly inferior in terms of weapons, in terms of effective manpower compared to the colonial troops such as the Tirailleurs sénégalais or the Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger , while these were always superior in terms of weapons technology. Examples are the Rif War (1909) , the Rif War (1921) , the Italo-Ethiopian War (1895–1896) , the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir and the Portuguese Colonial War .

Asymmetric Warfare Strategy

The Varus Battle , the attack by Arminius against Varus on the battlefields around the Teutoburg Forest , is a typical example of successful asymmetrical warfare, which deliberately avoided open field battles in order to wipe out the superior Roman opponents in one-on-one battles.

Asymmetric warfare ( called partisan warfare outside of the scientific discussion ) has always existed. The struggles of the early Confederates and Dithmarscher or even earlier of the Slavs (see Landing of the Slavs in the Balkans ) can be counted among them. This involved a small number of unorganized peasant groups who, thanks to their excellent knowledge of the terrain, had significant advantages over the better equipped knights on horseback.

The armed resistance, for example in Spain against Napoleon in the 19th century or in World War II against Hitler ( Resistance ), chose asymmetrical warfare without any substantial ethical doubts as to its justification. In contrast to the usual fighting outside of densely populated areas of the population, asymmetrical wars are very often associated with high numbers of casualties among civilians who are not actually directly involved in the fight. This offers an excellent hiding place for the warring party, which is weaker in terms of weapons, in which technically ever more sophisticated systems of modern, high-tech armies are promising in the short term, but quickly dull in their effect (see constant bloody incidents in Afghanistan and Iraq).

This hiding and unexpected slamming of asymmetrical belligerents (pinpricks) quickly leads to frustrations at the lower command level when carried out consistently within modern armies with the risk of escalation, which then results in sudden massacres of the civilian population (like My Lai in the Vietnam War ) and non-compliance with a Can express a minimum of humanity, since the irregulars can dive into it at any time and like to abuse it as a protective shield. From a humanitarian point of view, even warring democracies can quickly be expected to underestimate human life, as is regularly practiced by the other side anyway. Democratic states also run the risk of betraying their own moral ideals by committing the same crimes as their guerrilla opponents. A historical example is the fight of the French army in the Algerian War of Independence , in which there were numerous reprisals against the local population as possible supporters of the Front de Liberation Nationale (FLN) and against prisoners of the guerrilla after they fell into their hands, but also and above all killed Algerians who were friendly to the French and attacked French civilians with terrorist means such as bombs in Algiers.

A characteristic of asymmetrical acts of war is often that the losing side has the option of retreating to a neutral country, into which the other side cannot and does not want to carry out any acts of war. Examples are South Vietnam with North Vietnam , Laos and Cambodia; Oman with Yemen; Algeria with Tunisia and Morocco; Malaysia with Indonesia and today Afghanistan again with Pakistan.

Basically, the symmetrical belligerent party is generally superior to the asymmetrical belligerent party, but in some cases inferior due to the mostly large area, and that the asymmetrical warring party dictates action, since a distinction between friend and foe or enemy and civilian population is mostly in the country foreign war party is not possible.

Even more stringent international regulations to protect human life in asymmetrical conflicts are hardly enforceable in practice, and humanitarian aspects have no significant effect. The inferior side consciously seeks to be close to the civilian population and leads the battle from among them in order to avoid the fire superiority of the conventional army. At the same time, it causes victims among the civilian population, which alienate them from their own conventionally fighting army or peacekeeping forces and drive forces into the arms of the unconventionally asymmetrical fighting forces. The commander of a high-tech army then sees any restriction of warfare through humanitarian regulations (because it is difficult to implement against an enemy who fights completely without rules) a devaluation of his qualitative and quantitative superiority and rejects such regulations because they are predictable in his tactical range of operations make and thereby disadvantage and restrict. Asymmetrical fighters do not feel bound by such humanitarian regulations anyway, unless they can use them for propaganda purposes against the occupier , because they are not a party to such international regulations. Provoked excesses of violence by the conventional army are even an ideologically usable weapon and are therefore not entirely undesirable. The main suffering group in such conflicts is not the guerrilla force, but regularly the civilian population.

These attitudes of both asymmetrical warring parties pose a serious challenge to the further development and maintenance of current international humanitarian law, even during a war, unlike, for example, in 1907 on the occasion of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations , which were based on combatants of equal rank.

Unconventional warfare is tactically shaped by the inferior side, mostly through unconventional explosive devices and incendiary devices , booby traps , ambushes or fire attacks , and, more rarely, coups d'état , such as those used in hunting combat , as well as suicide bombers and car bombs . Since the enemy cannot or seldom be seen by the soldiers and security forces and cannot be put into action, the troops are worn down. In asymmetric warfare, the tactical telecommunications reconnaissance of the opposing troop telecommunications (combat and tactical telecommunications) is gaining in importance, since this is rarely veiled by the enemy and the telecommunications station can be cleared up through a lack of radio discipline, which usually also shows the position of the respective combat or tactical communications Leader is.

Material support and funding for asymmetrical warring parties

In most cases, an asymmetrical war party can only wage its fight in a state if it is supported by or by a “neutral” neighboring state and whose territory serves as a retreat in which no or very limited combat against the war party takes place.

In addition to conquering the resources of the war country, drug trafficking, ivory poaching, hostage-taking and extortion with the collection of a war tax and other means often serve as sources of finance. In recent times, organized crime has increasingly served to finance unconventionally asymmetrical forces.

Terrorism as a strategy of asymmetrical warfare

While the tactics of paramilitary struggle, i.e. the action of partisan organizations or similar, are primarily aimed at continuously weakening, provoking or demoralizing the militarily superior enemy with the strategy of "pinpricks", terrorism occurs as an offensive strategy asymmetrical warfare. Terrorists, unlike partisan or guerrilla units, can operate independently and thus carry the war out to other regions - even to the distant homeland of the enemy. Carrying out terrifying attacks with the highest possible media coverage is intended to unsettle the population and thus shake the political backing of the warring government. With direct attacks on the center of the enemy, terrorists want to break the perseverance of the population that stands behind the armed forces of the superior enemy. Thus in this form of war there is not only an asymmetry of forces and tactics, but also of the arenas and battlefields.

The term "asymmetric conflicts"

In the Pentagon, asymmetric conflicts are defined purely militarily as "asymmetric warfare". This is a narrowing of the view of the emergence and possible solutions of asymmetrical conflicts, which is not common in Germany. US Lieutenant Colonel John A. Nagl, who also fought in Fallujah in 2004, was one of the strongest critics of this exclusively military approach to asymmetrical conflicts . His study “Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam: Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife” from 2002 calls on the Pentagon to modernize the anti-terror strategy in the age of asymmetrical conflicts, which, according to Nagl, extends from the Vietnam War to Afghanistan to the Iraq war is based solely on massive firepower. He calls for a reflection on the British experience in Malaysia, where General Gerald Templer developed the concept of “ Winning hearts and minds ” and thus won with a combination of economic, social, political and military measures, and as one of several in the Vietnam War successive strategies by the US Army, but not consistently and too late. The experience of Vietnam shows that this must start early and therefore in good time as an action strategy for the “hearts” of the population in a crisis area before they join the militarily defeated war party through terrorist actions. This is why local protection is especially important for the rural population and their economic development, while at the same time accepting the lifestyle and religion of the various population groups. Like Afghanistan, Vietnam was represented by a national political group with which the local, especially rural, population did not identify, so that the opposing war party took sides.

The basic knowledge of Templar are:

- the guerrilla movement cannot be crushed militarily,

- the guerrilla movement must be separated from the people,

- the decision in the asymmetrical conflict is made in economic, social and political areas.

Another precedent for the successful solution of an asymmetrical conflict with the concept of “Winning Hearts and Minds” is the Dhofar War in the Sultanate of Oman from 1965 to 1975. A communist guerrilla group of around 2,000 men established itself in the Dhofar province and was killed in the Cold War was supported by the Soviet Union and China, had its bases in the neighboring People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (VDRJ) and could operate almost unhindered in the monsoon season in the densely forested and fog-covered coastal mountains. Militarily, the guerrilla force could not be crushed by the Omani armed forces, even because the Omani armed forces had the option to retreat to "neutral" Yemen and Saudi Arabia.

In 1970, Sultan Qaboos overthrew his father and then consistently applied the British concept he had learned about at the Sandhurst Military Academy . An amnesty was issued - a fighter who defected was not punished. He was immediately taken over into a newly founded militia of the Sultan, was allowed to keep his weapons and received a salary. All mountain villages were connected to the road network and each hut was connected to the energy network. A shop selling western goods, a school, and an infirmary were opened in each village. Then the government gave fridges and color televisions to the villagers. With this she awakened the desire in the villagers to earn money in order to be able to buy the new tempting goods. This was only possible if the villagers no longer fought for the guerrillas, but entered the service of the sultan. By 1975 more than 90 percent of the guerrilla fighters defected to the sultan. The rest was crushed in asymmetrical actions by the Omani armed forces and the British SAS, because the guerrilla movement and people were now separated.

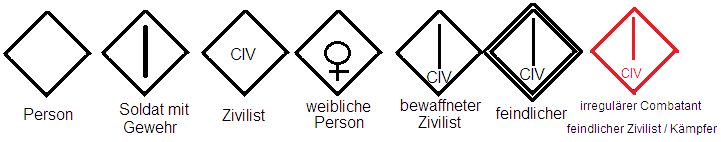

Tactical signs in asymmetrical warfare

See also

- FM 3–24 Counterinsurgency

- Covert fight

- Jagdkampf and Jagdkommando

- partisan

- Organized crime

- Police fight

literature

- John Arquilla : Insurgents, raiders, and bandits. How masters of irregular warfare have shaped our world , Chicago (Ivan R. Dee) 2011, ISBN 978-1-56663-832-6 .

- Frank Kitson : In the run-up to the war. Defense against subversion and riot . Seewald Verlag, Stuttgart 1974, ISBN 3-512-00328-1 .

- Maximilian Schulte: Asymmetrical Conflicts. An international law consideration of current armed conflicts between states and non-state actors . 2012, ISBN 978-3-8300-6529-6 .

- Ivan Arreguín-Toft: How the Weak Win Wars. A Theory of Asymmetric Conflict . Cambridge University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-83976-1 .

- Andrew James Birtle: US Army counterinsurgency and contingency operations doctrine, 1942-1976 . Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington DC 2006, ISBN 978-0-16-072960-7 .

- Andrew James Birtle: US Army counterinsurgency and contingency operations doctrine, 1860-1941 . Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington DC 1998.

- Carsten Bockstette: Jihadist Terrorist Use of Strategic Communication Management Techniques . In: Marshall Center Occasional Paper . No. December 20 , 2008, ISSN 1863-6039 ( marshallcenter.org [PDF]).

- Sebastian Buciak (ed.): Asymmetrical conflicts in the mirror of time . Publishing house Dr. Köster, Berlin 2008, ISBN 3-89574-669-X .

- Jacques Baud, Christine Lorin de Grandmaison: La guerre asymétrique ou la défaite du vainqueur . Éditions du rocher, 2003, ISBN 2-268-04499-8 .

- Mary Kaldor : New and Old Wars. Organized Violence in a Global Era . Stanford 1999.

- Markus Holzinger: Re-symmetry of asymmetry: On the repercussions of asymmetrical conflicts on the rule of law security architecture . In: Operations. Journal of Civil Rights and Social Policy . No. 1 , 2010.

- Steven Emerson : Secret Warriors. Inside the Covert Military Operations of the Reagan Era . GP Putnam's Sons, New York 1988, ISBN 0-399-13360-7 .

- Franz von Erlach , lieutenant colonel in the federal artillery staff: The wars of freedom of small peoples against large armies . Haller'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Bern 1867.

- Dirk Freudenberg:

- The universality of the methods of irregular forces using the example of the concepts of Hans von Dachs and Carlos Marighellas . In: Thomas Jäger / Ramus Beckmann (eds.): Handbook of war theories . Wiesbaden 2011, ISBN 978-3-531-17933-9 , pp. 310-322.

- Theory of the irregular: partisans, guerrillas and terrorists in modern guerrilla warfare . VS, 2008, ISBN 978-3-531-15737-5 .

- Bernhard Rinke: Peace and Security in the 21st Century. An introduction . Ed .: Wichard Woyke. Vs Verlag, 2004, ISBN 978-3-8100-3804-3 .

- Herfried Münkler : The New Wars . Rowohlt, 2004, ISBN 3-499-61653-X .

- Schröfl, Pankratz: Asymmetrical warfare . Nomos, 2004, ISBN 3-8329-0436-0 .

- Schröfl: Political Asymmetries in the Era of Globalization . Peter Lang, 2007, ISBN 978-3-631-56820-0 .

- Schröfl, Cox, Pankratz: Winning the Asymmetric War . Peter Lang, 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-57249-8 .

- Stephan Maninger: Who dares wins - Critical remarks on the use of Western military special forces in the context of multiple conflict scenarios . In: Austrian military magazine . No. 3 . Vienna 2006.

- Hans Krech : The fall of the GDR as a catalyst for the global end of the Cold War - a lecture in the 2004 General Staff course at the Bundeswehr Leadership Academy, Berlin . In: Contributions to peace research and security policy . tape 19 . Publishing house Dr. Köster, 2005.

- John A. Nagl: Counterinsurgency Lessons from Malaya and Vietnam: Learning to Eat Soup with a Knife . Praeger Frederick, 2002, ISBN 978-0-275-97695-8 .

- Hans Krech: Armed Conflicts in the South of the Arabian Peninsula. The Dhofar War 1965–1975 in the Sultanate of Oman and the Civil War in Yemen in 1994 . Publishing house Dr. Köster, Berlin 1996, ISBN 978-3-89574-193-7 .

- Hans Krech: The Afghanistan Conflict (2002-2004). Case study of an asymmetric conflict. A manual . In: Armed Conflicts after the End of the East-West Conflict . tape 15 . Publishing house Dr. Köster, Berlin 2004, ISBN 978-3-89574-540-9 .

- Ismail Küpeli (Ed.): Europe's "New Wars": Legitimizing State and War . Hinrichs, Norbert, Moers 2007, ISBN 978-3-9810846-4-1 ( wordpress.com [PDF; 1000 kB ]).

- Herfried Münkler: The change of the war. From symmetry to asymmetry . Velbrück, Weilerswist 2006, ISBN 978-3-938808-09-2 .

- Travis S. Taylor, et al .: An Introduction to Planetary Defense - A Study of Modern Warfare Applied to Extra-Terrestrial Invasion . BrownWalker Press, Boca Raton 2006, ISBN 1-58112-447-3 .

- James Stejskal: US Special Forces in Berlin, Detachment "A" and PSSE-B "- Secret missions in the Cold War (1956-1990) , from the American by Colonel a. DFK Jeschonnek, Verlag Dr. Köster Berlin 2017, ISBN 978- 3-89574-950-6 .

- Richard Duncan Downie: Learning from Conflict: The US Military in Vietnam, El Salvador, and the Drug War . Praeger, Westport CT 1998, ISBN 0-275-96010-2 .

- Mark Mazzetti : Killing Business. The CIA's Secret War . From the American by Helmut Dierlamm and Thomas Pfeiffer. Berlin-Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-8270-1174-9 .

- Beatrice Heuser : rebels, partisans, guerrillas. Asymmetric wars from ancient times to today . Schöningh, Paderborn u. a. 2013, ISBN 978-3-506-77605-1 .

- Felix Wassermann: Asymmetrical Wars. A political-theoretical investigation into warfare in the 21st century . Campus Verlag, Frankfurt a. M. u. a. 2015, ISBN 978-3-593-50314-1

- Vladimir Lenin : The Partisan War . First published in Proletari No. 5 v. Chr. September 30, 1906, reprinted in: Lenin Werke , Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1972, Volume 11, pp. 202-213

- Josef Joffe : Stones versus Missiles - Why the West cannot win asymmetrical wars . In: Die Zeit , No. 31/2007

- Liang Quiao / Wang Xiangsui: Unrestricted warfare. China's master plan to destroy America ( Chao-xian-zhan ), Dehradun (Natraj Publ.) 2007, ISBN 978-81-8158-084-9 .

- Nicholas Warndorf: Unconventional Warfare in the Ottoman Empire - The Armenian Revolt and the Turkish Counterinsurgency, Manzara Verlag, Offenbach am Main 2017, ISBN 978-3-939795-75-9 .

- Edward J. Erickson: Ottomans and Armenians: A Study in Counterinsurgency, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, ISBN 978-1-349-47260-4 .

- Edward J Erickson: A Global History of Relocation in Counterinsurgency Warfare, Bloomsbury Academic, London 2019, ISBN 978-1-350-06258-0 .

Movie and TV

- The invisible uprising (F / I / FRG 1972, director: Constantin Costa-Gavras )

- Death squads: How France exported terror ( Escadrons de la mort: L'école française , German: Death squads: The French School , Doc, F 2003, directed by Marie-Monique Robin )

Web links

- CA Fowler: Asymmetric Warfare: A Primer . (English)

- Carsten Bockstette: Jihadist Terrorist Use of Strategic Communication Management Techniques . (PDF; 938 kB) Marshall Center Occasional Paper # 20, December 2008 (English)

- Richard Norton-Taylor: Asymmetric Warfare: Military Planners Are Only Beginning to Grasp the Implications of September 11 for Future Deterrence Strategy . (English)

- Robert N. Charette: Open Source Warfare . November 2007

- Jonathan B. Tucker: General information on asymmetric warfare at forum.ra.utk.edu (English)

- Carlos Marighella : Mini-manual do Guerrilheiro Urbano ( Mini-manual of the urban guerrilla ). São Paulo 1969, German version , Portuguese version

Individual evidence

- ↑ James Stejskal US Special Forces in Berlin , see under literature