Burma campaign

| date | January 1942 to July 1945 |

|---|---|

| place | Burma (Myanmar) |

| output | Allied victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

Allies : United Kingdom British India National Burmese Army China United States |

Axis Powers : Japan Thailand Azad Hind ( INA ) National Burmese Army |

| Commander | |

|

|

|

| Troop strength | |

|

|

|

| losses | |

Japanese conquest 1941/42

Bilin - Sittang - Pegu - Toungoo - Taukkyan - Yunnan-Burma - Shwedaung - Prome - Yenangyaung

1942/43

Arakan I - The Hump - Chindits

1944

Arakan II ( Ngakyedauk ) - U-gō ( Imphal - Sangshak - Tennis Court - Kohima ) - Myitkyina - Mountain Song

1944/45

Meiktila / Mandalay - Pokoku -

Arakan III ( Kangaw and height 170 - Ramree ) - Operation Dracula ( Elephant Point ) - Sittang

The Burma campaign was a campaign during the Pacific War in World War II . Allied units fought against troops of the Japanese Empire and its allies. The fighting in Burma (now Myanmar ) began in January 1942, a few weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and the subsequent entry into the war by the United States . The Japanese troops of the 15th Army , which were commanded by General Iida Shōjirō , crossed the Burma- Thailand border in mid-January 1942 , and within a few weeks they were able to reach the capital, Rangoon . The aim of the Japanese campaign against Burma was, on the one hand, to cut off the supply and supply lines between British India and the territory held by Chinese Kuomintang troops near Chungking across the eastern foothills of the Himalayas , in order to achieve the Second Japanese, which had been in existence since 1937 - End Chinese War . During the rapid Japanese advance, the British and Indian troops of the British Commonwealth , as well as some Chinese units of the national Chinese government under Chiang Kai-shek , who should have defended Burma against a Japanese invasion, were almost completely wiped out within a few months, where they went as far as Chindwin -The river had to recede. However, in late 1942, American ( Merrill's Marauders ) and British ( Chindits ) guerrilla forces were able to commit several sabotage and guerrilla actions behind the Japanese lines, and in early 1944 British and American forces were able to go back on the offensive, with Japanese units up were driven back to Rangoon. After this first advance, the Allied troops were able to recapture almost all of Burma from the Japanese occupiers by July 1945, but it was not until the official Japanese surrender on September 2, 1945 that the last Japanese troops surrendered in the south.

background

British-Indian troops had conquered Burma as early as 1885 as a result of the Third Anglo-Burmese War . The country was incorporated into the Crown Colony of British India in 1886 . The Konbaung monarchy was overturned and the country was taken over by a British Governor General who was under the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London . Several smaller independence movements in Burma were crushed by the colonial power between 1895 and 1932. The biggest rebellion, the Saya-San uprising , broke out in 1930 and could only be suppressed after two years. The Buddhist leader of the uprising, Saya San, was then sentenced and shot. However, after the Saya-San uprising, British supremacy was no longer challenged until the outbreak of the Pacific War. In 1937 Burma was officially separated from British India. A new constitution and the status of a crown colony should give the Burmese greater opportunities to participate in the administration of their country. Simultaneously with the separation from British India, however, nationalist activities also grew in Burma, especially under the student Dobama Asiayone ("We Burman Association"; informally called Thakins ).

At the end of the 1930s, the British government of Burma, based in Rangoon, decided for the first time to combine the British armed forces in Burma into a single Burma army consisting of British and Indian soldiers. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 was then seen by some Burmese nationalists as an opportunity to force concessions from the British colonial power in return for aiding the war effort. Others, including the Thakin movement under Kodaw Hmaing , refused to support the war, and the Thakins were waiting for an imminent Japanese invasion. After France's defeat by Nazi Germany in 1940, British Governor General Sir Archibald Cochrane tried to procure more weapons and equipment for the Burma Army. He thought it would not be able to withstand a Japanese invasion. Deliveries from the UK, however, decreased noticeably over time, as much of the weapons produced were kept in England to defend against an expected German landing .

Allied troop strength 1941

At the end of 1941, shortly before the outbreak of the Pacific War, the Burma Army consisted of around 50,000 soldiers, including 4,621 officers. Among the remaining troops were around 30,000 Indian soldiers : most of them were battle-hardened Sikhs and Gurkhas , but who did not have enough weapons and ammunition. About 20,000 soldiers were British, and nearly all of the senior officers. These troops, which were inadequately equipped with heavy weapons and aircraft, were joined by around 10,000 Chinese soldiers belonging to the Y-Force , the national Chinese armed forces in Indochina. These Chinese units were also poorly armed, as their armament consisted only of aging American Springfield M1903 or captured Arisaka Type 99 rifles. They also had no heavy artillery . By November 1941, the strength of the Burma Army had increased to around 60,000 men, but with the exception of the British and a few Indian units, the remaining soldiers were insufficiently trained and armed. In November 1941, the Royal Air Force in Burma only had 69 P-40 Warhawk fighters, 28 Hawker Hurricanes and about 30 Brewster Buffalo fighters, which were inferior to the Japanese fighters. In December 1941 it was clear that this army would have no chance against a possible Japanese invasion. Anti-aircraft guns , tanks and modern combat aircraft were missing. However, Great Britain and the USA promised Governor Cochrane under the Lend Lease Act to ensure adequate equipment by March 1942.

The British-Indian units in Burma were initially under the supreme command of General Claude Auchinleck , until command passed to General Archibald Wavell on July 5, 1942 . General William Slim took command of the Indian forces of the Burma Corps in March 1942 , returning these dispersed troops from northern Burma to India. In the course of the campaign, the National Burmese Army (later Patriotic Burmese Forces (PBF)), whose guerrilla troops had fought with the Imperial Japanese Army since the beginning of the Japanese attack, changed sides. Chinese troops of Y-Force were strengthened in the course of the campaign by two more complete national Chinese armies, however, were the beginning of 1942, under the command of Chiang Kai-shek, as of March 1942 under the command of the US Militärabgesandten General Joseph Stilwell stood . In addition, there was the 1st Burmese Division , commanded by Major General James Bruce Scott , an independent association. It was reformed into the Burma Corps from March 1942 .

Japanese preparations

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of war, plans for the invasion and conquest of Southeast Asia were formulated in the Imperial Army Ministry in Tokyo . Prime Minister and Minister of War Hideki Tojo , Chief of Staff Marshal Sugiyama Hajime , Minister of the Navy Osami Nagano and the entire Imperial General Staff established the final plan of conquest that would follow the attack on Pearl Harbor as early as February 1941. This plan of operations was presented to Emperor Hirohito on November 2, 1941 , who approved it on the same day and released it for implementation. The Philippines , several American bases in the Pacific such as Wake Island and the Mariana Islands , the Dutch East Indies , British Malaya , Singapore , British Borneo and Burma were to be attacked by Japanese troops a few days after the declaration of war. Burma owned and has numerous oil wells around the city of Yenangyaung , which were a vital resource for the Japanese war industry. In addition, linen , rubber and large quantities of rice were produced in Burma . Since Burma bordered directly on French Indochina and Thailand , which had already been occupied by Japanese troops, the British bases in Burma and, above all, the military facilities in the capital, Rangoon, were within direct reach of the Japanese armed forces. According to the Japanese Army Ministry, the attack on Burma had to take place as soon as possible after the declaration of war before the British troops could launch an attack on Indochina. It was also crucial to cut off enemy troops in Burma from the British fortress of Singapore in order to cut off the supply and supply lines of the defenders of Singapore. Therefore, the invasion of Burma shortly after the start of the war with the attack on Pearl Harbor was strategically indispensable.

The Japanese plan of attack

The Japanese General Staff had already drawn up an operational plan for the planned attack on Burma in October 1941. This envisaged first attacking the British units in southern Burma and in the capital Rangoon, and cutting them off from the rest of the garrison in the north. If the encirclement of the British troops around Rangoon should not succeed, the Japanese armies involved should push back the enemy troops as far as Sittang and take Rangoon. With this plan, however, it remained open what would happen after the conquest of Rangoon and whether one should first turn to the British occupation in the north or first liberate the most important towns and roads in the south. In November 1941, General Iida Shōjirō , commander of the Japanese troops involved, personally requested the Burma operations staff to include in the plans after the conquest of Rangoon an advance northwards so as not to give the dispersed British troops an opportunity to rally. War Minister Tojo also agreed to this plan. The commanders of the two Japanese armies designated to carry out the operation against Burma, in particular General Iida, who would be in tactical command during the operation, have been informed of this decision. To interrupt communication with Singapore, the border between Burma and Malaya of Iida's troops should be taken and saved, while the Japanese advance should heavy air attacks on Allied troops in Rangoon, Mandalay and the major traffic artery of the Burma Road , the North Burma led to China, in order to prevent any enemy troop movements.

Intended troops

A regular Japanese unit, the 15th Japanese Army , which consisted of the 33rd and 55th Infantry Divisions and was commanded by Lieutenant General Iida Shōjirō, was planned for the conquest of Burma . This unit comprised around 38,000 men. These were well-trained soldiers, mostly veterans, who had mostly been relocated to Thailand from China and Manchukuo . These troops were seasoned and battle-hardened men supported by machine guns and other heavy infantry weapons, but most soldiers were armed with relatively simple Arisaka Type 99 rifles. There were also supply and supply problems with the 15th Army, which arose due to the few trucks and motorized units and were particularly noticeable in the lack of food and fuel . There was also a lack of communications equipment, vehicles, large-caliber ammunition and other items that were not sent to the 15th Army as they were sent to General Yamashita Tomoyuki's army operating in the Malay Peninsula . Because of the shortage of radio equipment, the connection between the individual associations was particularly susceptible to interference. In addition, there were no armored or paratrooper divisions in the 15th Army that would allow a rapid advance. The formations of the two divisions of the 15th Army on the Burma-Thailand border were widely scattered and in the event of an enemy counterattack in Burma they were unable to be quickly drawn together to face the enemy with a continuous front.

The troops of the 15th Army were later reinforced by the 28th Japanese Army under Lieutenant General Shōzō Sakurai and the 33rd Japanese Army under Lieutenant General Masaki Honda and from March 1943 formed the Burma Regional Army , a combat-tested, trained and still well armed unit, its operations headquarters was in Rangoon. Also fought on the side of the Japanese conquest troops in Burma and the Thai Northwest Army , the Indian National Army under the Indian revolutionary leader Subhash Chandra Bose and the National Burmese army, which made Thakin consisted Troops and volunteers and the beginning of 1945 changed sides. The Thai troops of the Northwest Army and the Indian units under Subhas C. Bose consisted of drafted men who had no military training whatsoever. They were supplied with weapons and ammunition, transport and artillery by the Japanese troops, while the volunteers of the National Burmese Army mostly fought only with captured rifles.

Special features of the campaign

The Burma campaign was characterized by some political, geographical and climatic peculiarities that could not be found in any other theater of the Pacific War .

From a political point of view, the most diverse interests of the war opponents involved clashed in Burma. Burma was part of the Empire of India until 1937, when it was declared a British Crown Colony . During the Second Sino-Japanese War , the British and Americans supplied the Chinese National Forces via the eastern foothills of the Himalayas . On July 17, 1940, under massive diplomatic pressure from the Japanese, the British closed the Burma Road, which was considered to be the most important supply line. However, they began to send new supply convoys on their way to China on October 18, as there were no further peace efforts between Japan and China. Chiang Kai-shek sent Chinese troops, known as the X-Force , to Burma in early 1942 to keep the supply routes open.

The geographical and climatic characteristics of the region with impenetrable jungles and swamps, the southern foothills of the Himalayas, monsoons, high temperatures and humidity were another special feature. Not only that the lack of infrastructure in the interior hindered the supply of military supplies, and that almost This could only happen by air, but also the high number of soldiers suffering from tropical diseases led to a suspension of the operations, which divided the Burma campaign into a total of four phases.

course

The Burma campaign can be divided into four phases. The first phase is from the Japanese conquest in January 1942, during which the troops of the British Commonwealth and the National Chinese Army stationed in Burma were pushed back from Burma by the well-established units of the Japanese 15th Army. The second phase is characterized by the many failed attempts by the Allies between the end of 1942 and the beginning of 1944 to regain a foothold in Burma. Phase three is the unsuccessful attempt at a Japanese conquest of India, the battles of Imphal and Kohima , as well as phase four from the end of 1944 to mid-1945, which ends with the reconquest of Burma by the Allies.

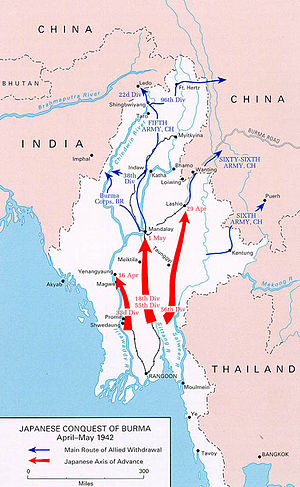

Japanese conquest of Burma in 1942

Entry of Japanese troops

On January 16, 1942, the two divisions of the Imperial Japanese Army invaded southern Burma from the Thai border. On January 16, the 33rd Division began their attack against the British front in southern Burma under the best weather conditions under Colonel General Shozo Sakurai . By around 7:00 p.m. on January 16, these troops had broken through the left wing of the defensive positions of the British and Indian soldiers of the Burma Corps and were advancing on the Salween River , while troops of the 55th Division advanced from the north. That same night, General Iida and Chief of Staff Sakurai ordered the pursuit of the British troops in order to encircle them at the few crossings of the Salween, while the British commander of the Indian troops in the area, General James Bruce Scott , immediately ordered the broken-in Japanese units through Cut off flank attacks by the 39th Indian Division (or 1st Burma Infantry Division) and the 17th Indian Division (Gen. Sir John Smyth ). These isolated counter-attacks by individual units, which also had no heavy artillery weapons, were quickly repulsed by the Japanese troops of the 33rd Division, and the English troops of the two dispersed divisions met on the morning of January 19 at one of the few bridges over the Salween . On the evening of January 19, Japanese advance formations of the 33rd Division were able to manage a strategically important, but due to omissions of the local commander Gen. Scott take undefended bridge over the river. However, after the translation of some enemy troops, this bridge was blown up by English pioneers .

A Japanese battalion of the 15th Army, on the other hand, took action against the right wing of the British front on January 19, where it met fierce resistance from British troops. It was only with the breakthrough of the entire 15th Army in the north that the Japanese battalion managed to bypass the British front through the gap. By January 20, this unit finally took several undefended villages on the eastern bank of the Salween. Almost at the same time, the remaining units of the Japanese 33rd Division advanced across the bank towards the last intact bridge from the north, which, however, along with its important defensive positions, was blown up by the withdrawing British troops. General Iida's forces advanced and with a battalion captured Victoria Point , which was heavily defended by British troops from the 17th Indian Division. After the conquest, the first Japanese airfield on Burmese soil was built on Victoria Point by Japanese pioneers and Chinese forced laborers . The important town of Tavoy fell to the Japanese troops of the 33rd Division on the evening of January 19, while British troops in the area fell back to the Salween. By taking Tavoy, the Japanese units were able to cut off all retreat options for the remaining 17th Division on the eastern bank of the Salween. It was no longer possible for the British unit, whose headquarters was in Mergui , to escape by land. On January 20, these troops chose the sea route, and 4,700 men escaped to Rangoon on several British transports by January 23. The remaining 10,000 men of the 17th Division withdrew to the Salween.

There was great confusion on the British side these days. The first Japanese air raids against Victoria Point and the towns of Mergui and Moulmein cut the telephone connection between the various British units stationed in the south. The operational reserve group of the Burma Corps in Rangoon could not be deployed as the general staff of the Burma Army in the city had not received any situation reports from the front since January 19. The only source of information was the operational aircraft of the two RAF reconnaissance squadrons in Rangoon, which had been flying armed reconnaissance flights over the contested areas in the south since January 20. Meanwhile, Gen. Thomas J. Hutton , Commander of the English Armed Forces in southern Burma, soon realized the danger that threatened his troops around the Salween. He therefore asked the General Staff of the Burma Army, and especially the Commander in Chief of the Allied Forces, Gen. Wavell, for permission to move to a flexible defense with alternative options in the Moulmein area. However, this was refused by General Wavell and Hutton was instructed to defend every meter of ground south of the Salween. In the event of a retreat, however, Hutton was ordered to blow up all the Salween bridges. The two bridges in the north had already been blown up on January 18, during the retreat of the 17th Division, but the southern crossings were still defended by British troops.

Japanese advance on Rangoon

With the retreat of the British from Victoria Point and Mergui on January 20, the Japanese troops of the 33rd Division fell into the hands of three more airfields that had already been built. Several military installations had been blown up by the English pioneers before their units were withdrawn. On the morning of January 21st, however, the first Japanese planes were able to launch an air raid on Rangoon, mainly bombing the docks and depots of the British troops at the port. On the same day, the Japanese fighters began to attack the roads in southern Burma in order to prevent any enemy troop movement. While the British troops withdrew from southern Burma for the Salween, the troops of the 55th Infantry Division also went on the offensive in the north of Mergui on January 22nd. The attack of the 55th Division of the 15th Army under Colonel General Iida broke through the British defense lines of the 1st Indian Division on the east bank of the Salween on the evening of January 22nd. The 55th Division pushed into the rear area on January 23rd and was able to take two bridges over the river on October 4th with some units of the 33rd Division, but British pioneers were able to destroy both crossings. The troops of the 55th Division advanced in the direction of Tenasserim , whereby the British troops of the 1st and 17th Indian Infantry Divisions were forced to retreat. The Japanese troops were able to take several enemy positions on the banks of the Salween on January 25th, but an intact bridge was not found by the Japanese reconnaissance planes because the British soldiers, according to the order received from Wavell, blew up all bridges after their crossing.

However, the 16th Indian Brigade, which was stationed in the small town of Kawkareik , was ousted by the enemy formations of the 55th Division by January 23, with the Indian soldiers suffering heavy losses from enemy air strikes. The troops of the 16th Brigade fled after the battle in a disorderly retreat to an area west of Moulmein, where they were reorganized by British officers. Meanwhile, the Japanese troops of the 55th Division tried to wipe out the Indian brigade by flanking attacks, but all Japanese attacks were repulsed by British troops with heavy losses of their own. The two commanders in the area of Moulmein Brigadier John Smyth of the 17th Indian Infantry Division and Lieutenant General Thomas J. Hutton, Commander in Chief of the Burma Army in the South, had different views on the defense of the Moulmein-Salween line, which is now held by the British General Staff in Rangoon had been chosen as the new line of defense ( Main Line of Resistance ). While Smyth wanted to retreat to the Sittang River in order to reorganize the Indian troops of the 1st and 17th Divisions there and to strengthen the combat strength of these troops for a later counterattack in a better environment, Hutton decided that every piece of land south of the Salween should be defended. Hutton prevailed at the General Staff in Rangoon and Smyth had to assign another Indian battalion of his 17th Division to the defense of Moulmein on the orders of General Wavell.

Defense of Moulmein

After several counterattacks by British troops around Moulmein had failed, Lieutenant General Hutton applied for a complete withdrawal of his front into the Moulmein-Salween line on January 29th. But it was not until the afternoon of October 5 that the last British troops stationed outside Moulmein arrived after a long retreat in the city. At the same time, General Hutton was subordinated to other Indian and British troops to strengthen the defense of Moulmein. On January 27, Hutton ordered the 1st Burmese Infantry Regiment to take up new defensive positions at the only remaining bridge over the Salween in this section. He also ordered two battalions of the Burma Army to form a defensive line about 20 kilometers from Moulmein in order to unify the defense in the Moulmein area. But these two units, which had been set back far, were already involved in battles against the 55th Division, a few kilometers west of Moulmein, so that they turned out to be a real reinforcement of the front.

Since his troops were numerically weak and battered, General Hutton tried by all means to stabilize the front at Moulmein. In several orders he demanded the full commitment of all soldiers and officers. In order to compensate for the loss of his troops' vehicles, he also had all available vehicles in the Moulmein area, including hundreds of single-axle wooden wagons owned by local farmers, requisitioned. The poor condition of the roads favored the British defense, as the Japanese troops could only advance slowly because trucks and armored vehicles could only drive on the largest roads. Hutton quickly realized that the Japanese units of the 55th and 33rd Divisions could only proceed on the solid roads. He therefore concentrated the few available British troops on the fixed access roads to Moulmein, with these troops erecting roadblocks and defensive positions.

Even during the fighting in the Moulmein area, however, the Japanese troops went to exploit the gaps they had made in the British lines in the Moulmein-Salween Main Line of Resistance . This also corresponded to the plans of General Iida and the Commander in Chief of the entire Southern Army , to which the 15th Army was subordinate, Field Marshal Terauchi Hisaichi . General Iida had ordered the 55th Division to proceed immediately after the capture of Kawkareik against the enemy lines on the Salween in order to take one last intact bridge and, if possible, proceed immediately towards Rangoon. However, the British General Staff had meanwhile taken measures to evacuate the British troops who were encircled in Moulmein, as General Smyth believed that the port was impossible to defend. On January 30th, after attacks by the enemy troops of the 33rd Division, about 9,000 men of the 1st Burmese Brigade, which was stationed in Moulmein, were able to cross the Salween with some requisitioned boats. Another 2,000 men were able to swim across the river, but about 1,600 British soldiers were captured by the attacking troops of the 33rd Division. In fact, the British troops at Moulmein had suffered great losses: after the end of the fighting for the city, according to English information, around 200 guns were captured. Around 2,400 men were killed in the Battle of Moulmein, while another 2,000 British were taken prisoners.

On February 2, the Japanese persecution forces were able to take some villages on the banks of the Salween and on the following day the last bridge over the Salween was blown up by British pioneers.

Battle of the Bilin River

The British troops of the 17th Division (Gen. Smyth), who were able to cross the Salween, were requested by the operations staff in Rangoon and above all by General Hutton to man new defenses on the Bilin River on February 13, but the English troops were already with Withdrawal all motor vehicles and guns were lost. Therefore, the Indian and British soldiers could not hold the well-fortified position on the Bilin River for long against some attacking Japanese units of the 33rd Division, which were supported by airplanes and had come across the Salween river thanks to a pontoon bridge and after three days of fighting had to Sittang draw back. The Japanese high command was now concerned to replace the exhausted forces of the 33rd Division, which had taken the positions on the Bilin on February 18, by the infantry forces of the 55th Division and thus the troops of the 33rd Division for a further advance to clear in the direction of Rangoon. However, the 55th Division made slow progress due to stubborn British resistance in the greater Bilin area, which had not yet been evacuated by all British units stationed there. After the end of the fighting for British positions at Bilin, the Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo and the High Command of the 15th Army were of the opinion that the enemy no longer had essential forces to defend Rangoon, since all British troops in the area had been crushed. But the planned advance on Rangoon could not be continued because from mid-February the 55th Division and its motorized forces no longer made any progress. The pursuing units of the 55th Division, which were supposed to encircle the dispersed British troops of the 17th Indian Division, were also in place. The 55th Division reported on February 19 that their motorized units were only making 2 km an hour because of the dense jungle and the rain showers that had occurred . An orderly supply of these troops was soon no longer possible. The Japanese planes were also less and less able to intervene in the fighting due to the bad weather.

Battle of the Sittang Bridge

On February 19, a few hours after the start of the retreat, the 17th Indian Infantry Division, which was in retreat after the battle on the Bilin River, received clearance from the operations staff in Burma to cross the Sittang River . General Smyth decided to go on a forced march with his exhausted Indian and British troops in order to reach the last intact bridge as quickly as possible. This bridge, over which the railway line from Peku, today's Bago , to Thaton ran, was built near the place Mokpalin . On the night of February 19-20, the Indian soldiers were able to move almost 50 km west of the advancing Japanese formations of the 33rd Division. However, two Japanese regiments of the 33rd Division were able to advance quickly over their flank on the following day to cut off the path of the British troops before they reached the bridge and thus encircle them together with the other units of the 33rd Division. On February 21, the Japanese fighters, which had been hindered by bad weather conditions in the previous days, were able to fly several additional air strikes against the advancing columns of the 17th Division, which suffered among other things from severe water shortages. With the abandonment of many vehicles, artillery and material as well as several hundred wounded, these troops continued to search their way towards the bridge over the Sittang, but were shot at several times by the units of the two Japanese regiments. At around 5:00 pm on February 21, General Smyth's British headquarters near the village of Kyaikto came under Japanese fire; however, the enemy troops consisted only of a few dispersed soldiers from the 33rd Division and could be repulsed by the Indian troops. Meanwhile, the first British units began to cross the bridge. Since Smyth feared an intervention by Japanese airborne troops, he ordered a Gurkha regiment to the west side of the bridge to protect it against enemy attacks or air landings. In the meantime, the first Japanese soldiers of the 33rd Division had reached the eastern area in front of the bridge and began with violent shelling, which killed several Indian medics at the end of the bridge. In addition, the Japanese planes were able to achieve several bomb hits against the British positions in front of the bridge, but the structure itself, which was about 550 meters long and made of solid iron , did not hit.

General Smyth now faced a difficult decision. If he brought the 17th Division completely to the west side of the Sittang, there was no way to destroy the bridge, and the Japanese had a free way to Rangoon. On the other hand, if the bridge was blown up, he would have to leave several brigades behind on the eastern side of the Sittang, and these troops would become prisoners of war. The British pioneers had already set up the charges under the bridge, but a number of British units were still on their way to the eastern end of the bridge. Some had been cut off by the Japanese air raids as several vehicles were destroyed. Others were cut off by flank attacks by Japanese forces in the jungle. The hotly contested Pagoda Hill right by the bridge changed fronts several times. The fight became more and more confusing. More and more access routes to the bridge were blocked by the Japanese and two British brigades were stuck near Mokpalin, without communication and with burning vehicles. The individual soldiers tried to get through to the bridge on their own. After several Japanese units had reached the bridge on the railway tracks on the east side, the British had hardly any ammunition left and holding the bridge seemed impossible, General Smyth gave the order to detonate it at 5:30 a.m. on February 23. The charges detonated shortly afterwards, causing part of the bridge to collapse. The British and Indian soldiers who stayed behind had no choice but to swim through the Sittang, which only a few succeeded in doing and which meant that they had to give up their weapons and ammunition. Other Indian units were encircled and destroyed by the Japanese while trying to reach the river. Individuals and scattered British soldiers were shot by the troops of the 33rd Division or were taken prisoner.

After the battle, the 17th Indian Infantry Division only consisted of 3,484 soldiers, about 40% of their original strength, which had been below target since the beginning of the campaign. Although the Japanese troops could have destroyed the enemy division, a quick advance on Rangoon was more important to them. The bridge, which was blown up by the British, could be repaired by the Japanese pioneers of the 33rd Division within only six hours, which allowed the units of the 33rd and 55th Divisions to cross the Sittang in full strength shortly afterwards. During the subsequent advance towards Rangoon, the Japanese troops carried with them about a third of the material left behind by the British soldiers on the Sittang.

Conquest of Rangoon

Battle for Pegu

After the British troops had suffered heavy losses on the Sittang and all counter-attacks by the Indian troops in the area had failed, General Wavell applied on February 25 to withdraw his front into the Rangoon-Yenangyaung line. In the meantime, however, General Harold Alexander , who had relieved Hutton and Smyth from command, had taken over the supreme command in Burma and, in view of the Japanese superiority, decided not to defend Rangoon, but at least to give the Japanese a strong defense readiness through a secure and only resistive retreat demonstrate. However, it was not until the afternoon of March 2 that all combat-ready troops, reinforced by M3 Stuart tanks of the 7th British Tank Brigade ( Brigadier John H. Astice ) and Indian troops of the 64th Infantry Brigade, were able to move into their positions in the new Main Line of Take Resistance . However, several Indian formations, which were far backward and were already attacked by Japanese troops of the 55th Division, which were supported by Type 95 Ha-Go tanks, could not occupy their positions. Some British infantry and tank units tried to rub the Japanese troops into the village of Pegu. When a squadron of the 7th Hussars, which belonged to the 7th Panzer Brigade, reached the town of Payagyi, north of Pegu , the English troops found that it was already occupied by the Japanese soldiers. Firefights broke out, visibility was poor and radio communications were difficult. After another brief exchange of fire by the British infantry, which was caught in a Japanese ambush west of Payagyi, some British managed to drive several Japanese soldiers out of the nearby jungle. The approaching British tanks opened fire and were able to take out two Japanese 95 Ha-Go tanks in the open. Another had been damaged so badly that its crew had to abandon it. Although the battle was quite confusing, the British infantry troops succeeded a little later in capturing four Japanese anti-tank guns before they were ordered to retreat through Pegu to Hlegu in order to meet the other units of the 7th Panzer Brigade. The British troops had to give up one of their tanks after the battle at Payagyi, but were able to destroy two more Japanese tanks on the way to Hlegu.

In the meantime, Pegu had been largely destroyed by the Japanese, but when the British reached the place in the dark they found the only bridge over the Sittang undamaged. Shortly before Hlegu, the Japanese soldiers of the 55th Division had set up a paved road block, which they defended against the advancing British tanks with small machine guns and Molotov cocktails . So they managed to take out one of the M3 Stuarts. After the British units were able to concentrate the fire on the roadblock with several tanks, the Japanese were forced to abandon it. The advancing British infantry units that passed through Pegu came under fire from isolated Japanese snipers . A number of soldiers were wounded and first cared for within the village. Finally the wounded were loaded onto small trucks and at the end of the convoy they were taken away through the captured Japanese roadblock.

Conquest of the capital

In the opinion of Alexander and the entire General Staff in Rangoon, the phase of static defense in the greater Rangoon area was considered to be over due to the great loss of land and the Burma Army was ordered to evacuate the city on March 7th . The British squadrons of the RAF and the American aircraft of the AVG (Flying Tigers) had been involved in fierce aerial battles by the Japanese aircraft in the previous weeks, which had destroyed a large part of the still operational Allied aircraft. Japanese Mitsubishi Ki-21 and Nakajima Ki-49 bombers had carried out several successful air strikes against Rangoon since early February, destroying or damaging many of the city's military installations. Above all, the port facilities on the Irrawaddy estuary and several anti-aircraft guns in the city had been destroyed by the enemy attacks. On March 7th, after about 4,000 troops of the 67th Infantry Brigade, the 7th Tank Brigade and the 16th Division had already left the city, General Alexander and General Wavell ordered a mining of the most important military installations, the port docks and the material left behind in Rangoon on. Around 400 Indian and British pioneers remained in the city to attach the loads and instruct the 500,000 residents of Rangoon about their behavior towards the approaching Japanese troops. All retreating Burmese, Indian or British soldiers of the Burma Army in the Rangoon area were punished by the death penalty from 7 March desertion from the Japanese troops .

On the same day, the major Japanese attack on Rangoon began with bombing by dive bombers and fighter planes and massive fire from field artillery and small mortars on the city center. The broad-based ground offensive was later launched. The motorized units of the 55th Division immediately advanced against the city center, while the infantry troops secured the surrounding hills and districts against light resistance from some scattered Indian soldiers. On March 8, the first Japanese tanks, accompanied by armed infantrymen and motorcycles , reached the docks on the banks of the Irrawaddy and were able to completely secure the entire city center after just a few hours. In the afternoon, Lieutenant General Iida arrived in the city, occupied some buildings in the center with the staff of the 15th Army and established his headquarters in Rangoon.

Further course of the campaign

The British-Indian units now in northern Burma were later supported by the Chinese troops under General Stilwell. But after more and more Burmese resistance turned against them and the civil administration in the areas still held collapsed, the leadership decided to retreat to India because of the very poor supply situation. This took place under extremely adverse circumstances. With complete disorganization, the units tried to take the narrow jungle paths to the north. In addition, the wounded and injured repeatedly caused considerable delays. Most of the equipment fell by the wayside and the steady and heavy rain that began shortly before reaching the border led to increasingly unhealthy conditions.

The onset of the monsoon and supply difficulties also led to the abandonment of the Japanese offensive operations in June after important transport hubs in northern Burma with Lashio and Myitkyina had been captured. The loss of the Burma Road from Lashio to Kunming prompted the Allies from April 1942 to build Ledo Road from Assam, India . Until this could be completed in early 1945, the Allies had to rely on air transport to support China (→ The Hump ).

On August 1, 1942, a Burmese government began work in Rangoon under the leadership of Ba Maw, who had previously been imprisoned by the British . The capture of Singapore , the most important British naval base in Southeast Asia, in February and the Japanese attack in the Indian Ocean in April 1942 had seriously shaken the position of the British in India. In the summer of 1942 calls for independence became louder and louder in India (→ Quit India resolution of the National Congress ). Part of the Indian national movement, led by Subhash Chandra Bose, split off from the National Congress and later founded a provisional government ( Azad Hind ), which from 1943 participated in the Burma campaign with troops from the Indian National Army , as did the National Burmese Army of Aung San after Burma declared independence from the UK in mid-1943.

Allied operations in Northern Burma

Meanwhile, the Allies undertook two counter offensives during the dry spell of 1942–1943. The first led to the Arakan region in an attempt to capture the Mayu Peninsula and Akyab Island , where an important airfield was located. The Japanese had built strong fortified positions there and were able to hold them. The approaching Allied troops suffered great losses. After the Japanese succeeded in bringing in reinforcements over an area that the Allies regarded as impassable, several Allied units were overrun. This led to the fact that they had to drop back behind the Indian border in the further course of the fight.

The second operation was controversial and was carried out by the newly established unit under Brigadier Orde Wingate , the Chindits . They pushed deep into Burmese territory behind the Japanese lines in order to interrupt the north-south railway connection, which was used by the Japanese as a supply route. During the operation, called Longcloth , about 3,000 soldiers entered central Burma. Although it was possible to interrupt Japanese communication lines and put the railway out of service for around two months, it cost very high losses.

Recapture 1943–1945

In August 1943 the Allies set up a joint Southeast Asia Command (SEAC) , which was headed by the British Louis Mountbatten at the end of 1943 . The British ground forces were continuously strengthened and placed under the command of General William Slim as part of the 14th Army established in October 1943 . In Ledo , the headquarters of major reaction from Chinese troops and led by Stilwell was Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC), the end of 1943 began an operation to retake Myitkyina. This change of command changed the situation in the combat area considerably. This was not least due to better training of the troops and better equipment, which also had an effect on the morale of the soldiers. The communication options were also improved and more use was made of air supply to the units.

In northern Burma, the Chinese advanced with a division from Ledo to Myitkyina and Mogaung from October onwards , while American construction crews, with the support of Indian workers, built Ledo Street behind them. The 18th Japanese Division was bypassed by the US special unit Merrill's Marauders , so that it threatened to be encircled. Further to the southwest, the Chindits penetrated deep into central Burma again during the large-scale air landing, Operation Thursday , established airfields and were able to operate behind the Japanese lines in Burma with a total of three brigades.

Despite major reservations at the Japanese headquarters of the Southern Army in Singapore about the plans of Lieutenant General Renya Mutaguchi , the new commander of the Japanese 15th Army, the Imperial High Command in Tokyo approved a campaign to India. In March 1944, the Japanese began Operation U-gō with the aim of capturing Imphal and Kohima , which failed with heavy losses until June. It was now noticeable among the Japanese that Japan could no longer adequately supply its troops. Above all, there was a lack of supplies. The massive attacks by the Allies against the Japanese transport ships had dramatically reduced their available shipping space, and the losses could no longer be compensated. Japan was now in retreat on all fronts. The Allies pursued the retreating Japanese to Chindwin until the end of 1944 . In August 1944, after a three-month siege, Myitkyina was captured by the Merrill's Marauders. Ledo Street was connected to Burma Street near Mongyu in November 1944 . This restored the most important supply route to West China.

In November 1944, the 11th Army Group (General Sir George Giffard ) was dissolved and a new Commander-in-Chief for the Allied Land Forces in Southeast Asia (ALFSEA) was established in the person of Lieutenant General Oliver W. Leese .

In early 1945, the 14th Army crossed the Irrawaddy in Operation Extended Capital and took Mandalay and Meiktila in March 1945 . Finally, in Operation Dracula , Prome and Pegu were liberated at the beginning of May and, on May 3, the Burmese capital Rangoon was occupied almost without a fight in an amphibious operation. They met a national uprising in which the National Burmese Army changed sides. The last organized Japanese resistance in Burma ended on the Sittang River in August 1945 .

Involved troops and associations

- Allies:

- Burma Corps (1942)

- Chinese Expeditionary Forces in Burma (1942)

- 5th Army

- 6th Army

- American Volunteer Group ("Flying Tigers", 1942)

- British 14th Army (including Indian and West African troops)

- Northern Combat Area Command (X Force, Merrill's Marauders)

- Chinese 11th Army Group

- Chinese 20th Army Group

- Tenth, Fourteenth and Twentieth Air Force (USAAF)

- Japan and allies:

- Japanese Regional Army Burma

- Northwest Thai Army

- Indian National Army

- National Burmese Army (changed sides in early 1945)

See also

literature

- India-Burma: The US Army Campaigns in World War II.

- Gerd Linde: Burma 1943 and 1944. The Orde C. Wingates expeditions. (Individual publication on the military history of the Second World War No. 10). Verlag Rombach, Freiburg 1972, ISBN 3-7930-0169-5 .

- Frank McLynn: The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph, 1942–1945. Yale University Press, New Haven 2011, ISBN 978-0-300-17162-4 .

- William Slim: Defeat Into Victory: Battling Japan in Burma and India, 1942-1945. Yale University Press, 1957. (Reprinted by Cooper Square Press, New York 2000, ISBN 0-8154-1022-0 .)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t India-Burma: The US-Army Campaigns in World War II

- ^ William Slim: Defeat Into Victory: Battling Japan in Burma and India, 1942-1945. 1957, p. 20.

- ^ A b Frank McLynn: The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph, 1942–1945. 1957, p. 25.

- ^ A b c d Frank McLynn: The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph, 1942–1945. 1957, p. 24.

- ^ A b Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, p. 35.

- ^ A b c d Frank McLynn: The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph, 1942–1945. 1957, p. 35.

- ^ Robert Farquharson: For Your Tomorrow: Canadians and the Burma Campaign. , 1995, p. 27.

- ^ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, p. 100.

- ^ A b Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, p. 37.

- ^ A b Louis Allen: Burma: The Longest War. 1984, pp. 24-35.

- ↑ a b c The Japanese Invasion of Burma below

- ↑ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Battle Studies: SITTANG DISASTER , under: TETAP29, a page that was compiled by employees of the Malay Army. ( Memento from January 29, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ a b c Rickard, J. (2 September 2009), Japanese conquest of Burma, December 1941-May 1942 , under: [1]

- ↑ a b c The 7th Armored Brigade - Engagements - 1942 (Withdrawal to Rangoon) ( Memento from August 28, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Frank McLynn: The Burma Campaign: Disaster into Triumph, 1942-1945. 1957, p. 29.

- ^ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, p. 34.

- ^ Donovan Webster: The Burma Road: The Epic Story of the China-Burma-India Theater , 2005, p. 34.