Augustalis

As Augustalis ( German "The Imperial" ) is a genus of gold coins Emperor Frederick II. Called that from December 1231 Brindisi and Messina were minted and distributed from June 1232. They were coined as part of the reorganization of the Kingdom of Sicily , in particular to promote long-distance trade and conduct larger commercial transactions. By depicting Frederick with a pallium and laurel wreath and the legend , they refer to the position of Frederick as Roman-German Emperor and thus had a propagandistic meaning in addition to the practical .

Due to their careful and skillful production method, the Augustals are counted among the most beautiful coins of the Middle Ages . Since it was also the first heavy gold coins to be minted in the West , they represent a turning point in the history of coins and money.

Causes and circumstances of the Augustal coinage

The Sicilian coinage before the minting of the Augustals

Since late antiquity, Sicily was first under Byzantine (6th – 9th century) and from the middle of the 10th century under Arab rule. After the complete Norman conquest of southern Italy in 1091, southern Italy and Sicily were finally united in 1130 by Roger II , the grandfather of Frederick II, to form the Kingdom of Sicily .

The Normans followed up on the coinage traditions of their predecessors and minted coins with Greek , Byzantine and Arabic motifs and lettering. The copper ( follares ) and silver coins ( ducales ) were mainly influenced by Byzantine, the gold coins ( tari ) were based on Arabic coins. After Sicily through the marriage of Constance of Sicily , the daughter of Rogers II, with the Staufer Heinrich VI. In 1194 it fell under Staufer rule, gold tari continued to be minted. The coins had a very light weight of only about 1 g and were increasingly of poor quality and shapeless appearance.

The reorganization in Sicily

After his coronation as emperor on November 22nd, 1220, Friedrich moved with a small entourage to southern Italy to reorganize the Kingdom of Sicily, where he was to spend a large part of his life and reign. The reforms served the "expansion of a tight centralized system of rule in the kingdom while suppressing the feudal structures." In addition to the establishment of an official state and the restriction of the rights of the local nobles, this reorganization included the expansion of trade and money transactions. Due to its exposed location in the center of the Mediterranean , there had been no interruption in the circulation of gold coins in southern Italy since ancient times, and Sicily had extensive trade relations, especially with countries with high gold deposits. Due to their low fineness and their often unaesthetic and untrustworthy appearance, the Goldtari no longer met the requirements, which is why the higher quality gold augustals began to be minted. In the Kingdom of Sicily, the coins were intended to complement the inferior gold tari and to replace the Byzantine hyperpyra and Arabic dinars that circulated in the Mediterranean region and also in Sicily , which were particularly dominant in long-distance trade.

Distribution area and use of the Augustals

The Augustals were probably produced in large numbers in Messina and Brindisi from December 1231 and distributed from June 1232. The chronicler Richard von San Germano reports for December 1231 on the production of the Augustals and in the following year on their distribution and their equivalent of ¼ ounce. The Augustals were mainly used in the Sicilian kingdom, but also in central and northern Italy. The two most important treasure finds come from Gela and Pisa and were hidden around 1280. Individual coins also made it to southern Germany and the crusader states . Copies were also sent to other European rulers, such as the King of England . The gold tariffs continued to be minted and remained in circulation.

Due to their comparatively high value, the Augustals were probably used for the processing of larger commercial transactions and continued to be minted for some time after Friedrich's death in 1250.

Technical specifications

Weight, size and composition

The weight of the Augustals is between 5.15 g and 5.35 g (mean: 5.258). If a surcharge of 1% for wear and tear is included , a target weight of 5.311 g can be concluded. This corresponded to the equivalent of ¼ Sicilian gold ounce. According to the Staufer coin order, the Augustals should be 20.5 carats fine and contain three parts silver and one part copper as alloy additives . The Augustals have a fine gold content of 85.5%, which corresponds to 4.54 g. The diameter of the augustals is between 19 and 21 mm.

In addition to the Augustals, semi-Augustals were struck. These had the same image program as the Augustals, were half as heavy with a diameter of 16 mm.

Legend and illustrations

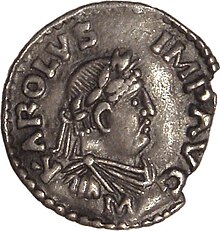

The obverse shows the antiquated, right-facing portrait of the emperor in profile . He wears a laurel wreath with a freely fluttering bow and a pallium, which is gathered on the right side with a ring fibula . The pallium has six or seven folds on the augustals and five or six folds on the semi-augustals. On the right upper arm you can see a bracelet or the border of an undergarment, which is decorated with four to twelve points, depending on the specimen. The circumferential inscription on the front is set in a pearl circle and reads C (a) ESAR AVG (ustus) IMP (erator) ROM (anus), with the “E” in uncials .

On the back of the Augustals an eagle turned half to the left with open wings and a head turned to the right can be seen. It has a strong beak and drawn down corners of its mouth. The legend is also enclosed in a pearl circle and reads FRIDE RICVS, here not with an uncial but with a Latin "E".

While the way of representation and the inscription are the same on all copies, the individual copies may differ in detail. This can affect both the image of Friedrich and that of the eagle. There are variations in the depiction of Friedrich's hair, headband and facial features, as well as variations in the thickness of the eagle's body, size and posture of the eagle's head and the eagle's wings.

Role models and propaganda significance

The pictorial program and the inscriptions on the Augustals were intended to depict Frederick as “the ultimate ruler of the Roman Empire”. Similar depictions of Emperor Augustus with a laurel wreath and gathered pallium seem likely as a model. Likewise, coins from Charlemagne and his son Louis the Pious , who were the last Roman-German emperors to be depicted in this way. There is also a resemblance to the coinage of Constantine the Great and his sons in terms of clothing and coin profile . Presumably there was no single model for depicting Friedrich on the Augustals. In order to clarify his position as a Roman emperor, a representation was chosen which shows him based on ancient and medieval models in the style of ancient kings.

The depiction of the imperial eagle on the back of the Augustals served a purpose similar to that used by Frederick . The eagle has been used as a symbol of rule and power since ancient times and can be traced back to the Roman legionary eagle (Aquila) . As part of the Translatio imperii , the symbol of the eagle was first transferred to the Frankish Empire and later to the Holy Roman Empire and appeared as an imperial symbol of rule on fibulae, seals , robes and insignia . With the minting of coins with the image of the imperial eagle - just as with his depiction in the style of ancient emperors - Friedrich makes his position as Roman-German emperor clear, a position that is also reflected in the 1231 constitutions of Melfi , the body of law for the Kingdom of Sicily, found again.

The fact that Friedrich is depicted on the Augustals, who were not minted for the Holy Roman Empire but only for the Kingdom of Sicily, exclusively as a Roman-German emperor and not as a Sicilian king, reflects his idea of an emperor . In addition to the universal empire, this also included the appeal to the rulers of late antiquity.

Portrait value of the imperial representation

Whether the portrayal of Friedrich is only in the context of the idealized image of the emperor or faithfully depicted above cannot be determined. Portrait likeness is usually rejected these days. The reasons given are the differences in detail in the individual embossing , as well as the fact that a portrait similarity was only attempted later. Since there is no reliable contemporary evidence of Friedrich's appearance, a portrait similarity can neither be confirmed nor refuted.

reception

Although the Augustals in Italy were replaced in the middle of the 13th century by the florins that were minted in Florence and Genoa from 1252 onwards, a broad reception of the Augustals can be seen, which continued through the entire Middle Ages, but also through the modern era . Even during Frederick's reign, the Augustals were mentioned in chronicles and a Sicilian poem. Frederick's depiction was also the model for coinage in Bergamo , which was friendly to the Hohenstaufen , but also for clergy seals, such as that of the papal secretary Bernardus de Parma . They served as a symbolic unit of coins in legal texts and chronicles until the 16th century.

The interest in the Augustals continued into the early modern period. They were represented in eleven copies in the coin collection of the Dukes of Este , one of the oldest coin collections ever, and were used as models in various works with images of Friedrich. Even in the early days of scientific numismatics , the Augustalis was treated as a research object. The first drawings of individual Augustals were finally published in the 17th century. In the 19th century Eduard Winkelmann and in the 20th century Heinrich Kowalski presented fundamental works on the Augustals. Kowalski provided a comprehensive, systematic list of the Augustals known to him with the suggestion of a chronological order.

In addition, the Augustal eagle remained the national symbol of Sicily after the fall of the Hohenstaufen and can be found on coins until the 19th century.

swell

- Richardus de Sancto Germano: Ryccardi de Sancto Germano chronica , ed. v. Carlo Alberto Garufi , Bologna 1937–1938 (Rerum italicarum scriptores: Raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento 7.2).

- Eduard Winkelmann: Acta imperii inedita, saeculi XIII et XIV. Documents and letters on the history of the Empire and the Kingdom of Sicily , 2 vol., Vol. 1: In the years 1198 to 1273 , Innsbruck 1880. Digitized

literature

- Peter Berghaus : Augustalis . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 1, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1980, ISBN 3-7608-8901-8 , Sp. 1218 f.

- Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. , In: Swiss Numismatic Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77-150. ( Digitized version )

- Wolfgang Stürner : Friedrich II. , 3rd, bibliogr. Completely updated and a foreword and documentation with additional information added. Ed., Darmstadt 2009. ISBN 978-3-534-23040-2 .

- Lucia Travaini : Augustale In: Federico II. Enciclopedia Federiciana. Roma 2005, Volume 1, pp. 131-133. ( online )

- Eduard Winkelmann : About the gold coins of Emperor Frederick II for the Kingdom of Sicily and especially about his Augustals , in: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 15 (1894), pp. 401–440 and 16 (1895), pp. 381–382.

Web links

- Augustalen in the interactive catalog of the Münzkabinett Berlin.

- Augustalis von Kaiser Friedrich II: 3D model in the culture portal bavarikon

Remarks

- ↑ For example with Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Swiss Numismatic Rundschau 55 (1976), p. 77–150, here: p. 77. Olaf B. Rader: Friedrich the Second. The Sicilian on the imperial throne. Munich 2010, p. 141.

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Schweizerische Numismati Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77–150, here: pp. 78f.

- ↑ Lucia Travaini: Augustale In: Federico II. Enciclopedia Fridericiana. Roma 2005, Volume 1, pp. 131-133. ( online ).

- ↑ Walter Koch: Friedrich II . In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages (LexMA). Volume 4, Artemis & Winkler, Munich / Zurich 1989, ISBN 3-7608-8904-2 , Sp. 933-939 (here Sp. 935).

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Schweizerische Numismati Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77–150, here: p. 77.

- ↑ Wolfgang Stürner: Friedrich II. Part 2. The Emperor 1220-1250. 3rd, bibliographically updated edition in one volume, Darmstadt 2009, p. 250.

- ↑ Richardus de Sancto Germano: Ryccardi de Sancto Germano chronica, ed. v. Carlo Alberto Garufi, Bologna 1937–1938 (Rerum italicarum scriptores: Raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento 7.2), p. 176. There it says: “Nummi aurei qui augustalis vocantur, de mandato Imperatoris in utraque sycla Brundusii et Messane cundutur. "

- ↑ Richardus de Sancto Germano: Ryccardi de Sancto Germano chronica, ed. v. Carlo Alberto Garufi, Bologna 1937–1938 (Rerum italicarum scriptores: Raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento 7.2), p. 181f: “Mense Iunii quidam Thomas de Pando ciuius Scalensis novam monetam auri, que Augustalis dicitur ad Sanctum Germanum detulit distribuendam per totam abbatiam et per Sanctum Germanum, ut ipsa moneta homines in emptionibus et venditionibus suis, iuxta valorem ei ab imperiali providentia constitutum, ut quidlibet nummus aureus recipiatur et expendatur per quarta uncie, sub pena personarum et rerum in imperialas idemis litter Thomas dedulit, annotata. "

- ↑ Wolfgang Stürner: Friedrich II. Part 2. The Emperor 1220-1250. 3rd, bibliographically updated edition in one volume, Darmstadt 2009, p. 251.

- ↑ Eduard Winkelmann: About the gold coins of Emperor Frederick II for the Kingdom of Sicily and especially about his Augustals. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 15 (1894), pp. 401–440, here: pp. 421f.

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Schweizerische Numismati Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77-150, here: pp. 94-96.

- ↑ Lucia Travaini: Augustale In: Federico II. Enciclopedia Fridericiana. Roma 2005, Volume 1, pp. 131-133. ( online ).

- ↑ The coinage of Messina and Brindisi stipulates: “Agustales auri, qui laborantur in predictic siclis, fiunt de caratis viginti et media, ita quod quelibet libra auri in pondere tenet de puro et fino auro uncias x. tarenos vii1 / 2; reliqua vero unica una et tareni viginti duo et medius sundt in quarta parte de ere et in tribus partibus de argento fino, sicut in tarenis. "Eduard Winkelmann: Acta imperii inedita, saeculi XIII et XIV. Documents and letters on the history of the Empire and the Kingdom of Sicily, 2 vol., Vol. 1: In the years 1198 to 1273, Innsbruck 1880, p. 766. Digitized

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Schweizerische Numismati Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77–150, here: pp. 95f.

- ^ Peter Berghaus: Augustalis. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Vol. 1, Col. 1218–1219, here: Col. 1219.

- ↑ For more information on the semi-Augustals, see Eduard Winkelmann: About the gold coins of Emperor Frederick II for the Kingdom of Sicily and especially about his Augustals. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 15 (1894), pp. 401–440, here: pp. 418f.

- ↑ Descriptions according to Winkelmann, Goldprägungen, p. 405, and Kowalski, Augustalen, p. 88. A brief description of the appearance of the Augustals can be found in connection with their distribution in June 1232 in Richard von San Germano: “ Figura Augustalise erat habens ab uno latere caput hominis cum media facie, et ab alio aquilam. “Cf. Richardus de Sancto Germano: Ryccardi de Sancto Germano chronica, ed. v. Carlo Alberto Garufi, Bologna 1937-1938 (Rerum italicarum scriptores: Raccolta degli storici italiani dal cinquecento al millecinquecento 7.2), p. 182.

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Schweizerische Numismati Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77-150, here: p. 88.

- ↑ Wolfgang Stürner: Friedrich II. Part 2. The Emperor 1220-1250. 3rd, bibliographically updated edition in one volume, Darmstadt 2009, p. 252.

- ^ Peter Berghaus: Augustalis. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Vol. 1, Col. 1218–1219, here: Col. 1219.

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Swiss Numismatic Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77–150, here: pp. 88–91.

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Swiss Numismatic Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77-150, here: pp. 91f.

- ↑ Eduard Winkelmann: About the gold coins of Emperor Frederick II for the Kingdom of Sicily and especially about his Augustals. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 15 (1894), pp. 401–440, here: p. 406.

- ↑ Lucia Travaini: Augustale In: Federico II. Enciclopedia Fridericiana. Roma 2005, Volume 1, pp. 131-133. ( online ); Wolfgang Stürner: Friedrich II. Part 2. The Kaiser 1220-1250. 3rd, bibliographically updated edition in one volume, Darmstadt 2009, p. 252.

- ^ Peter Berghaus: Augustalis. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters, Vol. 1, Col. 1218–1219, here: Col. 1219.

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Schweizerische Numismati Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77-150, here: pp. 81-84. On page 83 there are images of Grossi from Bergamo, as well as the seal impression of Bernardus of Parma.

- ↑ For example in Jacobus de Strada: Epitome thesauri antiquitatum, 1557, fig. 8.

- ↑ These can be found in: F. Paruta: La Sicilia descritto con Medaglie , Rome 1649, plate 143; and: CD Ducange: Glossarium ad Scriptores mediae et infimae Latinitatis , 3 vols., Paris 1678, new edition Paris 1937–1938, vol. I, col. 389.

- ↑ Eduard Winkelmann: About the gold coins of Emperor Frederick II for the Kingdom of Sicily and especially about his Augustals. In: Mitteilungen des Institut für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung 15 (1894), pp. 401–440 and 16 (1895), pp. 381–382.

- ^ Heinrich Kowalski: Die Augustalen Kaiser Friedrichs II. In: Swiss Numismatic Rundschau 55 (1976), pp. 77-150.