CO 2 tax

The CO 2 tax (also carbon tax , generic term: CO 2 levy , English: carbon tax ) is an environmental tax on the emission of carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) and possibly other greenhouse gases . The aim of such a tax is to reduce the negative effects resulting from these emissions - in particular global warming and the acidification of the oceans - by means of a higher CO 2 price . Consumers and companies should be informed of the costs of the climate impacts caused by a clear price signal . This is intended to make a significant contribution to lowering CO 2 emissions and thus to stabilizing the carbon dioxide content in the earth's atmosphere .

In the context of climate policy instruments, a CO 2 tax applies as a price solution as opposed to a quantity solution such as that represented by EU emissions trading .

Basics

The basis of assessment for a CO 2 tax is the CO 2 emissions that arise when burning fossil fuels . There are also consumption-related taxes such as the coal tax or mineral oil taxes , which can also be used for steering purposes, as well as surcharges on the taxes on special product groups. The assessment based on greenhouse gas emissions distinguishes a CO 2 tax in the true sense of the word from energy taxes based on the energy consumed, such as the German electricity tax . While energy taxes also cover the use of renewable and nuclear energy, this is not the case with CO 2 taxes.

In addition to CO 2 taxes, energy sources can be affected by many other taxes. The total tax burden of an energy source , converted to the CO 2 emissions caused by its use , is sometimes referred to as the implicit CO 2 tax .

Other greenhouse gases can be included in taxation by calculating their CO 2 equivalent .

Like other environmental taxes, CO 2 taxes are intended to have a steering effect. Market incentives are to be created to reduce emissions through higher prices for goods and services that are associated with high CO 2 emissions. Economic operators who minimize costs will first reduce emissions where this is cheapest possible. To do this, they can use lower-emission production methods, develop new processes, switch to products that cause fewer emissions or reduce the consumption of emission-intensive products. Due to their indirect effect via the market price on the level of emissions, CO 2 taxes are one of the market-based instruments of climate policy . According to the World Bank , this is an “economic instrument with which a cost-effective reduction in emissions from fossil fuels can be achieved”.

In addition, CO 2 taxes can also help to solve or mitigate other important problems, which is why the motivation for CO 2 taxes is no longer solely determined by climate protection, but also by positive side effects ( co-benefits ). These problems, which are of great importance in many countries around the world, include Examples include improving food security , a secure supply of clean water , access to environmentally friendly and affordable electricity, and preventing air pollution . CO 2 taxes are also discussed in political programs as an important part of a Green New Deal .

layout

Tax basis: The basis of taxation is usually the carbon content of energy sources or the greenhouse effect ( global warming potential ). Accordingly, the CO 2 equivalents of those emissions that are released when using energy sources are measured. Here it must be determined which greenhouse gases should be covered by the tax. Decentralized emission sources, such as methane emissions from agriculture, can be difficult to record and lead to high administrative costs. It is also conceivable to provide carbon sinks , for example forests from reforestation projects, with a “negative tax”, ie to subsidize them (see also climate compensation ).

Tax tariff : The tax tariff defines the amount of money to be paid per assessment unit, i.e. usually the amount of money to be paid per ton of CO 2 equivalent. The economically optimal level would be precisely the costs that the emission of an additional ton of CO 2 causes globally, the so-called social costs of CO 2 emissions ( Social Cost of Carbon ). In practice, however, these are nowhere near known; Estimates average US $ 196 with considerable variance (the standard deviation is US $ 322). Alternatively, the tax can be based on a defined emissions target , for example national emission reduction contributions according to the Paris Agreement (→ 1.5-degree target , two-degree target ) or a national emissions budget . When determining the amount, the implicit tax amount must be taken into account, which results from the inclusion of further, already existing taxes or subsidies. In 1999 in many European countries the implicit tax per tonne of CO 2 for coal was lower than that for natural gas. In order to achieve a desired price - also in relation to other energy sources - and a certain emission reduction cost-effectively, the introduction of a CO 2 tax can be combined with other changes in the tax system, which will reduce existing benefits for products with high emissions.

Production stage of taxation : CO 2 taxes can be levied at different stages along the production chain. In order to keep the administrative costs of the tax low, it is desirable to collect them in a few, easily controllable places. That speaks in favor of levying the tax directly on the extraction or import of fossil fuels. Emissions due to leaks or other activities that would otherwise not be considered in later stages are also included. If processes exist that permanently bind and dispose of CO 2 or other greenhouse gases in later stages of the production chain, for example carbon capture and storage (CCS) or CC usage , these avoided emissions would also be included in the tax. The level of tax collection also influences the visibility and thus the acceptance of the tax in the population.

Climate tariff (Border Tax Adjustments ): A country can, insofar as this is in accordance with international trade law, levy duties and taxes on imported goods or refund emissions taxes on exported goods. On the one hand, this can serve to avoid disadvantages for companies in international competition. On the other hand, it can also serve to reduce “gray emissions”, i. H. Include emissions from the production of imported goods abroad and avoid the relocation of emission-intensive production, the so-called carbon leakage , abroad.

Gradual Adoption ( Phase-in ): CO 2 taxes are usually introduced gradually and increased to help the economy adapt. An initially low tax combined with a credible plan for future tax increases would also create incentives for emission-reducing innovations and thus keep the initial and subsequent costs low.

Consideration of further external effects : Both activities that lead to climate change and acidification of the oceans as well as climate protection measures are associated with a number of further external effects. If, for example, CO 2 prices are introduced in isolation for fuels without accompanying measures , the substitution by biodiesel could lead to increasing land requirements. Such land use changes can on the one hand also contribute to rising greenhouse gas concentrations, on the other hand they can be associated with biodiversity losses. In general, there are connections between the different planetary borders at different regional levels, which must also be addressed by both market-based and non-market-based instruments and at different policy levels in order to avoid negative side effects of individual measures as far as possible.

Use of tax revenue : See section Use of revenue .

Effects

The CO 2 tax increases the price of the taxed carbonaceous products. This not only creates an incentive to reduce emissions, but can also have a number of other consequences, depending on how they are designed.

Reducing greenhouse gas emissions

A CO 2 tax primarily serves to achieve certain reductions in greenhouse gas emissions or to comply with a certain limit value for a country's total emissions. When it comes to structuring the tax, the state does not directly determine the amount of emissions, but influences it indirectly via the price. It remains uncertain to what extent the targeted amount of emissions will actually be achieved. The unknown factors include:

- Inflation , which reduces the net amount of tax,

- the price elasticity of market participants, i.e. the extent to which they react to a certain price change,

- Innovations that enable less emission-intensive production, or else

- the introduction of new products to the market that create new, unforeseen pressures.

For this reason, some states provide for an adjustment of the tax level in practice. The Scandinavian countries have linked the amount of their tax to inflation.

Reducing further environmental damage

Burning fossil fuels generally causes environmental damage through emissions of other pollutants, for example air pollutants such as soot particles or sulfur dioxide. By reducing the use of fossil fuels, the CO 2 tax also reduces further environmental damage. This positive side effect is mainly short-term and regional. Various studies come to some considerable additional environmental benefits ranging from two to several hundred US dollars per ton of CO 2 avoided .

Competitive effects

A CO 2 tax leads to higher costs for emission-intensive production factors. This has an impact on international competitiveness and possibly also on the competitiveness of industries within the country if the tax is not levied equally in all areas. Companies need some time and investment to convert their production to lower-emission technologies and goods. In the short term, they are therefore at a disadvantage compared to companies less affected by the tax if they cannot pass on higher costs to their customers. Competitive disadvantages could even cause companies to move their production to locations with lower costs. The extent to which companies are at a disadvantage not only in the short but also in the long term depends on how well the emission intensity of production can be reduced. In the long term, competitive advantages could also arise if the tax triggers corresponding innovations and increases in efficiency ( Porter hypothesis ).

Competitive disadvantages can be mitigated through a targeted use of tax revenue (see #Use of revenue ) or tax breaks, the latter making the tax less effective.

Because tax is only one of many factors influencing competitiveness, its competitive effect is difficult to examine. Initial studies from the 1990s indicated that competitive disadvantages were rather insignificant. There was evidence that energy-intensive industries such as oil refineries, aluminum manufacturing, and cement plants have partially relocated investment and production. At this point in time, there were no clear findings on any competitive advantages based on the Porter hypothesis .

Distributive Effects

The distributive effects of CO 2 taxes have received special attention . Here we look at the effect of the tax under Tax shifting : companies will try to pass on cost increases to customers. If the tax is not passed on to consumers in full, it will affect corporate profits and labor income. Passed-on costs lead to higher consumer spending or abstinence.

- The main question here is to what extent households are unevenly taxed in relation to their income and assets. In addition to higher prices for electricity, heating and travel costs, price changes for other consumed products must also be taken into account.

- The benefits of a CO 2 tax can also be unevenly distributed. The local population groups affected benefit above all from the reduction of further, often regional, environmental damage, such as better air quality.

- Households can also benefit differently from the use of tax revenue.

- Economists like Mathias Binswanger "Die Treadmühle des Glückes, Herder-Verlag" fear the rebound effect. The recipients of the repayment use it to buy goods, travel and services that cause the increase in CO2 to rise again.

Overall, CO 2 taxes tend to have a regressive effect . This means that households with low incomes are burdened proportionally more. This is mainly due to the fact that they spend a larger proportion of their income on heating energy and electricity. However, not all studies come to this conclusion; Individual case studies showed proportional burdens, i.e. no redistributive effect, or a slightly progressive effect, i.e. even a relatively higher burden on wealthy households. There appears to be a slightly progressive effect, at least in the European Union, in the transport sector. The state can correct the regressive effects of the tax through targeted use of tax revenue, for example in the form of tax and contribution relief, from which lower-income households in particular benefit. Alternatively, he can exempt heating energy and household electricity from the tax up to a certain limit or set a lower tax rate for this.

Use of the income

Tax reform : If the entire expected income from the CO 2 tax is returned to society as compensation measures for disadvantages, this is referred to as a revenue-neutral tax, as the tax rate is not increased. The double dividend hypothesis states that the tax can be cost-neutral through further positive effects, such as higher employment figures in the regenerative energy sector. An environmental bonus system based on the Swiss model - the CO 2 tax levied is paid out to the citizens at the end of the year in an amount that is the same per capita for everyone, which benefits those who have caused fewer CO 2 emissions - creates an acceptance-promoting system Framework for “the increase in the cost of resource consumption, which is desirable in terms of climate policy”.

Financing of environmental programs : Tax revenues can be earmarked for research, development and the use of renewable energies or more economical products. In this case they can trigger further reductions in emissions or the reduction of further environmental damage.

Compensation measures : They can serve to mitigate distributive effects or competitive effects of the CO 2 tax, for example through tax breaks elsewhere or subsidies.

Entries in the general budget : they can be entered in the state budget as revenue without being reserved for specific purposes. The state simply generates higher revenues.

CO 2 tax worldwide

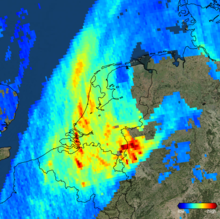

After the introduction of a relevant CO 2 tax in Finland in 1990, similar regulations slowly came into play around the world. In 2019, however, 20% of global greenhouse gases will be affected by such regulations. The World Bank provides current overviews on an interactive map with further details. In the broad climate discussion in the German media in 2019, reference was also made to the CO 2 tax in other countries.

In developing countries , the structuring of a CO 2 tax can pose particular difficulties. In addition, poor households are often only active in informal economic sectors and may not be covered by social programs. Compensation measures intended to reduce the regressive effects of a CO 2 tax on poor households can be particularly difficult to implement here.

CO 2 tax in the European Union

In the European Union , EU emissions trading , which covers around 45% of emissions, is the core instrument for achieving the European emission reduction targets. The EU Emissions Trading Directive expressly provides for the possibility of supplementary national taxes.

In its report to Chancellor Angela Merkel dated July 12, 2019, the Advisory Council for the Assessment of Macroeconomic Development stated that twelve EU countries raise national CO 2 prices in addition to EU trading in emission rights. In 2020, another country will join with the Netherlands. The majority of the heating and transport sectors are taxed. The amount of taxes and duties varies greatly. The EU Energy Tax Directive (2003/96 / EG) of October 27, 2003 forms the legal basis for energy taxes , such as the kerosene tax or taxes on fuels and electricity , in the respective national states as framework legislation . It also defines minimum tax rates and tax exemptions .

The guideline does not differentiate according to the harmfulness of energy products to the climate, but offers member states leeway for further grading taxes based on CO 2 intensities. Pure CO 2 taxes, which are based exclusively on the carbon content, do not, however, belong to the taxes harmonized by EU directives. According to the EU, energy consumption is responsible for 79% of total greenhouse gas emissions. That is why, as part of the Europe 2020 strategy, the member states have committed themselves to setting national targets for energy efficiency . Against this background, the Commission had submitted a proposal for an amendment to the Energy Tax Directive, which should enable the Member States to create a framework for CO 2 taxation in the internal market . This attempt failed in 2015, as did other attempts to base energy taxes across the EU based on CO 2 intensity.

Germany

The introduction of a CO 2 tax was called for in 1994 in the final report of the study commission “Protection of the Earth's Atmosphere” . The report stated that the Commission sees "the control via scarcity-based prices and the use of market forces as the priority way to achieve climate protection goals" and that a "greenhouse gas tax [...] can therefore be expected to have the greatest climatic ecological control effects". Such a tax is "an instrument of environmental policy with little bureaucratic effort and high efficiency". Therefore proposed the introduction of an EU-wide energy CO 2 tax and recommended that the Federal Government “should work with the European Union to ensure that a Union -wide energy CO 2 tax comes about”.

In December 2019, a national emissions trading system with fixed prices for the first five years from 2021 was adopted.

The decision of the Federal Constitutional Court of July 2017 on the nuclear fuel tax had placed high legal hurdles against the introduction of a CO 2 tax in Germany. According to the prevailing opinion , a design in the form of a taxation of the CO 2 emissions itself is ruled out because it cannot be subsumed under the types of tax provided for in the Basic Law and considered to be final. The design as a tax on coal, natural gas and oil, so-called energy tax, would be permissible.

The federal government's climate cabinet presented the climate package in September 2019 . This package of measures provided for the introduction of a CO 2 price of initially 10 euros per ton of CO 2 from 2021 along with other measures. To this end, on October 23, 2019, the Federal Cabinet passed the draft of the law on a national emissions trading system for fuel emissions ( Fuel Emissions Trading Act - BEHG). After negotiations with the Federal Council , the entry price was increased to 25 euros per ton.

France

Since 2014, the French tax on fuels and heating fuels , the Taxe intérieure de consommation sur les produits énergétiques (TICPE) , has included a proportion proportional to the carbon content, the “climate energy contribution ” (CCE ). In 2014 it was seven euros per ton of CO 2 . There, the fixed part of the tax, which is independent of the carbon content, was reduced by the same amount, so that the tax level remained unchanged overall in 2014. In the following years, the CCE should increase to 14.50 euros (2015) and 22 euros (2016) per ton of CO 2 without any further compensation . The French government intends to use the income to promote the expansion of renewable energies . Since 2018, one ton of CO 2 has been taxed at EUR 44.60. According to an overview by the World Bank, the French CO 2 tax is the most extensive in the world in terms of revenue. French electricity customers are relatively lightly burdened by the levy because the country's electricity industry has a high proportion of nuclear power and relatively little coal begins. However, the tax led to a high burden for frequent drivers, whereas in 2018 the yellow vests movement turned with sometimes violent protests. One of the concessions made by President Emmanuel Macron to the protesters was the cancellation of further increases. Originally, the tax should have reached € 86.20 per ton by 2022.

In July 2019, an environmentally-related air traffic tax was announced, which should bring in 180 million euros from January 2020 - depending on the class and route length from 1.50 euros to 18 euros per ticket. The tax will apply to flights that start in France, with exceptions for connecting flights and for Corsica and the French overseas territories. The proceeds will benefit the railway.

Great Britain

The UK has set itself the goal of reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 80% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels. In addition, the electricity sector is to be decarbonised by the 2030s . H. become largely CO 2 -free. To encourage the changeover, a minimum price of £ 18.08 per tonne (20.21 euros per tonne) will be charged on carbon dioxide emissions . This minimum price is calculated in addition to the costs resulting from EU emissions trading and, under the current market conditions, should be high enough to cause a switch from emission-intensive coal-fired to less emission-intensive gas-fired power plants.

Sweden

In 1991, a CO 2 tax was introduced in Sweden . With the introduction of this tax, the energy taxes that had been levied for some time were halved. The tax revenue flows into the general state budget. The tax rate rose from an initial 27 euros per tonne of CO 2 to 120 euros in 2019. Sweden has by far the highest implicit tax rate on CO 2 of all OECD countries .

Different sectors of the economy are burdened very differently by CO 2 and energy taxes. Private consumption, wholesale and retail trade, the public sector and services are particularly highly taxed. Various branches of industry that are in international competition, on the other hand, pay significantly lower tax rates; in 2010 it was around 21% of the full CO 2 tax rate. This proportion is expected to increase to 60% by 2015. In 2005, exceptions were planned for some industries in order to avoid a double burden from the EU emissions trading introduced that year . In addition, a tax was introduced in 2018 on all flights departing from Swedish airports. The fee is - depending on the distance - between 5.80 euros and 38.80 euros. Only stopping passengers are excluded.

Between 1990 and 2008, greenhouse gas emissions fell by almost 12%. It is difficult to determine to what extent this can be traced back to the CO 2 tax or other instruments such as emissions trading and energy taxes. Estimates are between 0.2% and 3.5%. In the same period, the gross national product doubled . Sweden is seen as an example of how reducing greenhouse gas emissions and economic growth can be reconciled.

Slovenia

Along with Estonia , Slovenia has had the most comprehensive CO 2 legislation in the EU since 2002 : The Uredba o okoljski dajatvi za onesna-ževanje zraka z emisijo ogljikovega dioksida ("Regulation on the environmental charge for air pollution caused by carbon dioxide emissions") from 17 October 2002, in revision C 44/2004 of May 1, 2005, contains provisions on emissions of CO 2 , NO X and SO 2 , so it is a far-reaching air pollution tax in the broader sense.

CO 2 tax outside the European Union

Australia

Under Prime Minister Julia Gillard , a carbon tax was decided in 2011 and introduced in mid-2012. The Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency is responsible . More than 50% of the income is to be used to reduce the burden on households and hard-hit companies. The tax rate was initially at AU $ 23 per ton of CO 2 (just under US $ 24) and is increasing by 2.5% annually. From July 2015 an emissions trading system should replace the tax. The government under Prime Minister Tony Abbott , newly elected in the parliamentary elections in Australia in 2013 , abolished the tax in July 2014.

Canada (British Columbia)

In July 2008, the Canadian province of British Columbia (BC) introduced a carbon tax of Can $ 10 per tonne of CO 2 equivalent on fossil fuels , the proceeds of which should be used to reduce other taxes and should therefore be income-neutral. The tax rate was gradually increased to Can $ 30 in 2012.

Since the tax was introduced, per capita consumption of these fuels has decreased by 17.4% in BC, while it has increased by 1.5% in the rest of Canada. The gross domestic product increased in the same period as in the rest of Canada. The CO 2 tax has reduced income tax in BC, and in 2012 it was the lowest compared to other Canadian provinces. A study from 2013 comes to the preliminary conclusion that it is a very effective measure that has effectively reduced the consumption of fossil fuels without having a negative effect on the overall economy. According to surveys, an increasing number of British Columbia residents are in favor of the CO 2 tax; in 2012, just under two-thirds of those polled were in favor.

In October 2016, the Canadian federal government passed the “Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change” (PCF). This plan forces the provinces either to introduce a CO 2 emissions trading system by January 2019 or to implement the nationwide Federal Carbon Tax , analogous to the model of the carbon tax in the province of British Columbia. By January 2018, Alberta and British Columbia had introduced such a carbon tax . Quebec and Ontaria, however, introduced an emissions trading system. The Federal Carbon Tax provides for a levy of Can $ 20 per t CO 2 in 2019. Thereafter, the tax increases annually by Can $ 10 until it reaches Can $ 50 in 2022.

The example of British Columbia shows how the rejection of a CO 2 tax can dissolve as soon as the benefits become visible to the public. For example, after the introduction of the CO 2 tax in British Columbia in 2008, calls for the tax to be canceled after the population received discounts on income tax and greenhouse gas emissions fell.

Mexico

Mexico has been levying a tax on fossil fuels produced and imported in the country since 2014. The carbon emissions that the fuel causes in addition to natural gas are taxed. As a result, natural gas is not taxed. The amount of the tax is limited to 3% of the sales price. Companies can pay the tax not only in monetary terms, but also with certificates from Mexican clean development mechanisms . The tax is between one and four US $ per ton of CO 2 , depending on the fuel. The tax covers around 40% of Mexico's CO 2 emissions.

Switzerland

CO 2 release and redistribution

The CO 2 -Abgabe in Switzerland is an incentive tax on fuels in the amount of 96 CHF per ton, it is an extension to fuels such as gasoline and diesel under consideration. The state pays part of the income from the levy back to citizens through health insurance . On December 10, 2018, a CO 2 tax on flight tickets ( air traffic tax ) was rejected by the National Council by 93 votes to 88 with 8 abstentions.

Today (as of 2019) all citizens pay an incentive tax, which is included in the price of the fuel (oil and natural gas products). The total tax currently amounts to CHF 1.2 billion per year. The levy is now to be increased significantly in the course of the 2020s: from CHF 96 to a maximum of CHF 210 per tonne of CO 2 . The greater part (currently two thirds) of the CO 2 levy is distributed back to the population through health insurance premiums. Together with other environmental taxes, all households are currently credited with CHF 77 per capita. The CO 2 levy paid by the economy is also largely repaid to the companies. A third of the CO 2 levy flows into the building program; a more comprehensive climate fund is proposed. Petrol and diesel importers have to compensate for a larger part of the CO 2 emissions and can pass on the associated costs with a surcharge of a maximum of 10 cents per liter (12 cents from 2025). There are also plans for a new ticket tax of between CHF 30 and CHF 120 per ticket.

South Africa

South Africa introduced a CO 2 tax on June 1, 2019 . It is the equivalent of US $ 8.34 per ton of CO 2 equivalent. The tariff, to which there are numerous exceptions, is to apply until 2022 and then increase.

Comparison with other instruments of climate policy

Conditions and prohibitions

Politicians can regulate emission sources directly through conditions. These include, for example, emission standards , speed limits or time or zone driving bans.

Emissions standards can, among other things, set limit values for CO 2 emissions for motor vehicles. Manufacturers are then forced to meet these requirements, even if they could achieve a higher emission reduction elsewhere at the same cost. A market-based approach such as the CO 2 tax, on the other hand, allows market players this leeway, and it is hoped that it will result in lower avoidance costs compared to a policy of restrictions.

Emissions trading

In international agreements, emissions trading has so far been used as a market-based instrument of climate policy. A maximum amount of emissions is specified here. Participants must acquire emission rights in order to be able to emit greenhouse gases. The rights are tradable. So there is a maximum amount of emissions given, while the price is variable, one speaks of the volume-based approach . In contrast to this, in the case of a CO 2 tax, politicians set a price, while the amount of emissions can fluctuate, so it is a price-based approach ( standard price approach ).

The two instruments differ in their effectiveness if the price or quantity cannot be set precisely at the level at which the avoidance costs are exactly outweighed by the damage avoided. This is the case, for example, when damage and avoidance costs are not precisely known. The damage caused by global warming is likely to increase slowly with the amount of greenhouse gas emitted in the short term, while avoidance costs increase sharply. A CO 2 tax that is not set at the optimal level is likely to miss the target only a little, while a non-optimally defined amount of emissions will fall far short of it and thus lead to higher economic losses in the short term. In the long term, on the other hand, innovation is likely to result in relatively slowly rising avoidance costs and disproportionately increasing damage. In this case, a specified, tradable amount of emissions is less likely to miss the target and comes closer to the long-term economic optimum. Emissions trading and taxes can be complementary instruments in climate policy.

The states named in Annex B of the Kyoto Protocol have committed themselves to participate in international emissions trading and to comply with certain emission limit values . The instrument of international emissions trading can be supplemented by national instruments in order to meet certain reduction commitments. The CO 2 tax can take on the role of such a national instrument and, for example, bring about reductions in sectors that are not covered by emissions trading. For example, since 2014 France has paid a “ climate energy contribution ” to motor fuels and heating fuels that are not covered by the EU emissions trading system .

reception

In January 2019 the published Wall Street Journal a statement of more than 3,500 US economists that a CO 2 -tax connected to a repayment for every citizen in the same amount as the climate dividend advocated. Such a tax is "the most cost-effective lever to reduce carbon dioxide emissions," according to economists. Among others, 27 Nobel Prize winners signed the appeal.

The economist Jean Pisani-Ferry formulates doubts about the social acceptance of CO 2 taxes as part of a Green New Deal . Many citizens wanted to continue to consume and travel as before. Perhaps they found a little less meat and more economical cars as well as a change of profession associated with advantages to be acceptable. However, they are hardly ready for more. The transition to a carbon-neutral economy will inevitably lead, according to Pisani-Ferry, "that we will be worse before we are better, and the weakest segments of society will be particularly hard hit." Old, inefficient production facilities are to be decommissioned , which requires corresponding investment funds in more energy-efficient new systems - estimated to be in the order of two percent of the gross domestic product in 2040. Correspondingly less will then be available for private consumption. According to Pisani-Ferry, a complete social redistribution of the proceeds from the carbon tax is an option to mitigate the consequences. In addition, in an environment of “ultra-low interest rates”, debt financing is a rational method “to accelerate the economic transition while at the same time spreading the costs over several generations”.

Similarly, see Murielle Gagnebin and Patrick Graichen from the think tank Agora energy revolution . Above all, support should be given to those sections of the population - as taught by the yellow vests movement in France , for example - who pay the CO 2 contributions but can hardly avoid them: “The nurse , for example, who gets in with her old car at all times of the day and night The hospital has to commute, or the farmer who lives in the country and has to heat with heating oil because his farm is not connected to the gas network and who cannot reduce his consumption quickly by insulating his old walls. ”For such population groups should According to Gagnebin and Graichen, a special fund will be created to support, for example, the purchase of fuel-efficient vehicles, energy-efficient renovation and the installation of heat pump heating systems .

In a joint statement in May 2019, the head of the International Monetary Fund , Christine Lagarde , and the IMF director for fiscal policy, Vítor Gaspar , spoke out in favor of global carbon pricing. In order to meet the climate protection targets agreed in the Paris Agreement, a CO 2 price of around US $ 70 per tonne (equivalent to around 62 euros) must be charged. There is a growing consensus that this is the most efficient tool for reducing fossil fuel consumption and the associated greenhouse gas emissions. Lagarde has long been calling for pricing, and an IMF study from 2016 also confirmed the necessity.

The economists Reiner Eichenberger and David Stadelmann declared at the beginning of 2020 that the climate problem would be “surprisingly easy to deal with” if the costs were true . Future damage would have to be scientifically estimated and charged to today's polluters via a CO 2 tax, whereby the levy would have to apply to all emitters without exception. In this context he refers to the demands of William Nordhaus , of a group of “over 3,500 American economists with 27 Nobel Prize winners” and of the IMF. Much of the income would have to be used to lower other taxes. At the same time - in comparison to other approaches such as the GLP initiative “Energy instead of VAT” - incentives for outsourcing production processes to countries with lower environmental standards would be avoided. Political resistance comes primarily from providers of alternative energies and energy-saving technologies, since their subsidies would no longer apply , and from energy-intensive industries as the largest sources of CO 2 .

See also

- CO2 price

- CO 2 price with climate dividend , i.e. H. Reimbursement in equal parts to all citizens

- Effects of global warming on viticulture

- Consequences of global warming in Germany

- Consequences of global warming in Europe

- Consequences of global warming in Austria

- Coal tax , mineral oil tax

- Emissions trading

Web links

Carbon Pricing dashboard of the World Bank

literature

- Andrea Baranzini, José Goldemberg, Stefan Speck: A future for carbon taxes . In: Ecological Economics . tape 32 , 2000, Survey, pp. 395-412 , doi : 10.1016 / S0921-8009 (99) 00122-6 .

- Nicholas Stern: The Economics of Climate Change . Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-70080-1 , The Stern Review, pp. 351-367 .

- Jenny Sumner, Lori Bird, Hillary Smith: Carbon Taxes: A Review of Experience and Policy Design Considerations . Ed .: National Renewable Energy Laboratory [NREL]. NREL / TP-6A2-47312, December 2009 ( nrel.gov [PDF]).

- International Monetary Fund (IMF): Working Paper 18/193: Mitigation Policies for the Paris Agreement: An Assessment for G20 Countries (August 2018)

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Andrea Baranzini, José Goldemberg, Stefan Speck: A future for carbon taxes . In: Ecological Economics . tape 32 , 2000, Survey, pp. 395-412 , doi : 10.1016 / S0921-8009 (99) 00122-6 .

- ^ World Bank: Putting a Price on Carbon with a Tax .

- ↑ Ottmar Edenhofer , Susanne Kadner, Jan Minx: Is the two-degree target desirable and can it still be achieved? The contribution of science to a political debate. In: Jochem Marotzke , Martin Stratmann (Hrsg.): The future of the climate. New insights, new challenges. A report from the Max Planck Society. Beck, Munich 2015, ISBN 978-3-406-66968-2 , pp. 69-92, here pp. 88f.

- ↑ "But unlike economists' favorite climate change strategy - setting the fair price for carbon while leaving everything to private decision-making - the Green New Deal rightly encompasses the many dimensions of the fundamental transformation required to successfully combat climate change of our economies and societies. "( Jean Pisani-Ferry : Arguments for green realism. This is how the costs of a CO2-free world can be distributed fairly. In: Der Tagesspiegel , March 2, 2019, p. 6. Online version , accessed on 29. March 2019)

- ^ A b c Charles D. Kolstad, Michael Tolman: The Economics of Climate Policy . In: K.-G. Mäler, JR Vincent (Ed.): Handbook of Environmental Economics . tape 3 . Elsevier BV, 2005, chap. 30 , doi : 10.1016 / S1574-0099 (05) 03030-5 .

- ^ A b Donald B. Marron and Eric J. Toder: Tax Policy Issues in Designing a Carbon Tax . In: American Economic Review . tape 105 , no. 5 , May 2014, p. 563-564 , doi : 10.1257 / aer.104.5.563 ( taxpolicycenter.org [PDF]).

- ↑ Baranzini et al: A future for carbon taxes. 2000, table 1

- ↑ World Bank (Ed.): Guide to Communicating Carbon Pricing . December 2018, p. 8.21-23.49 ( worldbank.org ).

- ↑ Dana Ruddigkeit: Border Tax Adjustment at the interface of world trade law and climate protection against the background of the European emissions certificate trading . In: Christian Tietje and Gerhard Kraft (eds.): Contributions to transnational commercial law . Issue 89, 2009, ISBN 978-3-86829-151-3 ( telc.jura.uni-halle.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Petra Pinzler, Mark Schieritz: CO 2 -renzausgleich: Klimazoll . In: The time . December 11, 2019 ( zeit.de [accessed December 27, 2019]).

- ^ Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (ed.): Global Biodiversity Outlook 3 . 2010, p. 77 ( cbd.int ).

- ^ Måns Nilsson, Åsa Persson: Can Earth system interactions be governed? Governance functions for linking climate change mitigation with land use, freshwater and biodiversity protection . In: Ecological Economics . 2012, doi : 10.1016 / j.ecolecon.2011.12.015 .

- ↑ Baranzini et al: A future for carbon taxes. 2000, pp. 406-407.

- ↑ Baranzini et al: A future for carbon taxes. 2000, pp. 405-406.

- ↑ Baranzini et al: A future for carbon taxes. 2000, chapter 3

- ↑ Baranzini et al: A future for carbon taxes. 2000, chapter 4

- ↑ Roland Schaeffer: debate yellow vests and climate targets: eco correct, socially unjust . In: The daily newspaper: taz . December 3, 2018, ISSN 0931-9085 ( taz.de [accessed December 7, 2018]).

- ↑ Carbon Pricing Dashboard. The World Bank Group, August 1, 2019, accessed November 14, 2019 .

- ^ CO2 tax: Common practice in Northern and Western Europe. In: BR. July 17, 2019, accessed July 20, 2019 .

- ↑ a b c d Hartmut Kahl and Lea Simmel: European and constitutional scope for CO 2 pricing in Germany . In: Foundation for Environmental Energy Law (Ed.): Würzburg studies on environmental energy law . No. October 6 , 2017, ISSN 2365-7138 ( stiftung-umweltenergierecht.de [PDF]).

- ↑ Climate protection: Economic practices recommend CO2 tax on fuel and heating oil , ZEIT online, July 12, 2019

- ↑ Experts are for CO2 tax, NTV-Text (Teletext / Videotext) page 107 Fri. July 12, 2019 16:33

- ↑ Directive 2003/96 / EC (PDF) of the Council of October 27, 2003 on the restructuring of the Community framework for the taxation of energy products and electricity (Energy Tax Directive)

- ↑ Decision C (2014) 3136 of the European Commission, final of May 21, 2014, Rn. 40.

- ↑ Final report of the study commission “Protection of the Earth's Atmosphere”, p. 488f. . October 31, 1994. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ↑ Bundestag report: CO2 tax could be unconstitutional . August 8, 2019, ISSN 0174-4909 ( faz.net [accessed September 5, 2019]).

- ↑ Individual questions on the tax systematic classification of a CO2 tax. Scientific Services of the German Bundestag, July 30, 2019, accessed on September 5, 2019 .

- ↑ The state must not invent taxes . In: Verfassungsblog . ( verfassungsblog.de [accessed on September 26, 2018]).

- ↑ Draft bill for a law on a national emissions trading system for fuel emissions (dated October 23, 2019 with comments). Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, accessed on November 14, 2019 .

- ↑ Taxe carbone: comment ça va marcher. In: La Tribune. September 22, 2013, accessed December 20, 2013 .

- ^ Robin Sayles: France adopts 2014 budget; carbon tax on fossil fuels. In: Platts . McGraw Hill Financial, December 19, 2013, accessed December 20, 2013 .

- ↑ Manager Magazin (Hamburg): Worldwide models for new levies: This is how the CO2 tax could work , June 3, 2019

- ↑ MDR Aktuell : France announces CO2 tax on flight tickets , July 9, 2019

- ↑ UK Department of Energy and Climate Change (Ed.): Planning our electric future: a White Paper for secure, affordable and low-carbon electricity . 2011, ISBN 978-0-10-180992-4 ( gov.uk [PDF]).

- ↑ Carbon floor price hike will trigger UK coal slowdown, say analysts. In: The Guardian . April 2, 2015. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ↑ Brigitte Knopf, Matthias Kalkuhl: CO2 price: Taxing CO2 and repaying the money to the citizens . In: The time . February 7, 2019, ISSN 0044-2070 ( zeit.de [accessed March 6, 2019]).

- ↑ Sumner et al. a .: Carbon Taxes: A Review of Experience and Policy Design Considerations. 2009, pp. 11-12.

- ↑ a b c d Stéphanie Jamet: Enhancing the Cost-Effectiveness of Climate Change Mitigation Policies in Sweden . In: OECD Economics Department (Ed.): Working Papers . No. 841 , 2011, p. 9, 15-18 , doi : 10.1787 / 5kghxkjv0j5k-en .

- ↑ Sweden introduces environmental tax for air passengers. In: The press. April 1, 2018, accessed July 13, 2019 .

- ↑ Fouché Gwladys: Sweden's carbon-tax solution to climate change puts it top of the green list . In: The Guardian , April 29, 2008. GDP - Gross Domestic Product (PDF)

- ↑ Alexander Cotte Poveda, Clara Inés Pardo Martínez: CO 2 emissions in German, Swedish and Colombian manufacturing industries . In: Regional Environmental Change . tape 13 , no. 5 , October 2013, p. 979-988 , doi : 10.1007 / s10113-013-0405-y .

- ^ Ecological taxes in Slovenia. Ecological-Social Market Economy Forum (foes.de, accessed April 27, 2015).

- ↑ energie-experten.org: Australia resolves CO2 tax . November 8, 2011 ( energie-experten.org ).

- ^ Tom H. Tietenberg: Reflections — Carbon Pricing in Practice . In: Reviews of Environmental Economics and Policy . 2013, doi : 10.1093 / reep / ret008 .

- ↑ Till Fähnders: Full power back Australia is abolishing climate tax . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . July 17, 2014 ( faz.net ).

- ↑ Stewart Elgie, Jessica McClay: BC's Carbon Tax Shift After Five Years . An Environmental (and Economic) Success Story. Ed .: Sustainable Prosperity, University of Ottawa . July 2013 ( energyindependentvt.org [PDF; 4.6 MB ]).

- ↑ The Environics Institute (ed.): Focus Canada 2012 Climate change: Do Canadians care still? S. 4 ( environicsinstitute.org (no longer valid original) [PDF]). environicsinstitute.org ( Memento of October 21, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Stepping Up to the Plate: Canada Releases Draft Legislation for Proposed Federal “Backstop” Carbon Pricing System. Retrieved September 22, 2018 .

- ^ State of the Framework Tracking implementation of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change . doi : 10.1163 / 9789004322714_cclc_2017-0028-024 .

- ↑ Murray, B. & Rivers, N. Energy Policy 86, 674-683 (2015).

- ↑ World Bank (Ed.): State and Trends of Carbon Pricing . Washington DC May 2014, 5.2.9 ( wds.worldbank.org [PDF; 9.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Cordula Tutt: Carbon Dioxide Tax: Where CO2 already costs real money. Retrieved July 19, 2019 .

- ↑ CO2 tax: How a tax could stop climate change, Zeit report from September 5, 2017, accessed on September 5, 2017.

- ↑ No CO2 tax on flight tickets. In: schweizerbauer.ch . December 11, 2018, accessed May 4, 2019 .

- ↑ Tenants, homeowners, drivers, frequent fliers - this is how the CO2 Act works , Fabian Schäfer, NZZ 23 September 2019

- ↑ Jenny Gathright: South Africa's carbon tax set to go into effect next week. npr.org of May 26, 2019 (English), accessed May 31, 2019

- ↑ Nicholas Stern: The Economics of Climate Change . 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-70080-1 , The Stern Review, pp. 351-367 .

- ^ Economists' Statement on Carbon Dividends - Bipartisan agreement on how to combat climate change. In: Wall Street Journal. January 16, 2019, accessed June 12, 2019 . Declaration website: Economists' Statement on Carbon Dividends. Retrieved February 8, 2020 .

- ^ Jean Pisani-Ferry: Arguments for Green Realism. In this way, the costs of a CO2-free world can be distributed fairly. In: Der Tagesspiegel , March 2, 2019, p. 6 ( online version , accessed on March 29, 2019).

- ↑ Murielle Gagnebin and Patrick Graichen: Learning from France how it doesn't work. The CO2 tax and the yellow vest protests could help Germany to improve its climate and social policy. In: Der Tagesspiegel , March 24, 2019, p. 8.

- ↑ International Monetary Fund advocates global CO2 tax . In: Die Zeit , May 4, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ↑ FISCAL POLICIES FOR PARIS CLIMATE STRATEGIES-FROM PRINCIPLE TO PRACTICE . International Monetary Fund website. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ↑ Christine Lagarde , Vitor Gaspar : Getting Real on Meeting Paris Climate Change Commitments . International Monetary Fund website. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ↑ IMF calls for global CO₂ tax. Retrieved on May 13, 2019 (German).

- ↑ http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2016/sdn1601.pdf

- ↑ Guest comment: If politicians approached the climate problem honestly and efficiently, it would be easy to deal with - by means of cost truth. In: nzz.ch. January 3, 2020, accessed January 11, 2020 .