Chicago School (Economics)

In economics , Chicago School refers to an economic program developed at the University of Chicago in the 20th century (the term school is used here to mean school of thought ).

In addition to the rather spontaneous and unplanned genesis (development) of a research group, a second process took place in the scientific and public discussion from the mid-1940s, in the course of which the Chicago School was stylized into a brand name. The Chicago School did not appear in literature until after 1950, and it was not until 1960 that it became a stand-alone school widely known among economists.

With Milton Friedman , Theodore W. Schultz , George Stigler , Ronald Coase , Gary Becker , Merton Miller , Robert Fogel , Robert E. Lucas , James Heckman and Eugene Fama, the University of Chicago has more than twice as many Nobel Prize winners and Alfred- Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics who taught there while the prize was won, such as Harvard and Princeton . The recipients of the Nobel Prize or the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize were Paul Samuelson , Kenneth Arrow , Herbert A. Simon , Lawrence Klein , Tjalling Koopmans , Friedrich von Hayek , Gerard Debreu , James Buchanan , Trygve Haavelmo , Harry Markowitz , Myron Scholes , Edward Prescott , Vernon L. Smith , Edmund Phelps and Roger B. Myerson worked in Chicago before or after winning the Nobel Prize. The Chicago School shaped economic thinking like no other in the second half of the 20th century.

Conceptual content

Chicago School is not used in a uniform way; a distinction can be made between:

- Chicago School in the strict sense: refers to those scientists who actually taught at the University of Chicago in the 20th century .

- Chicago School in the broader sense: denotes a certain school of thought in economics, which can be summarized into a uniform school through the assumptions mentioned under teachings .

Basic assumptions

Despite their heterogeneity, the following features are characteristic of the theoretical structures of their representatives:

- Neoclassical price theory: Any economic behavior can be explained using neoclassical price theory .

- Market economy: Free markets are the most efficient means of resource allocation and income distribution . This goes hand in hand with the tendency to reduce the economic activity of the state in case of doubt.

In 1974 Milton Friedman described the following as essential characteristics:

“In discussion of economic science,“ Chicago ”stands for an approach that takes seriously the use of economic theory as a tool for analyzing a startlingly wide range of concrete problems, rather than as an abstract mathematical structure of great beauty but little power; for an approach that insists the empirical testing of theoretical generalizations and that rejects alike facts without theory and theory without facts. In discussions of economic policy, “Chicago” stands for belief in the efficiency of the free market as a means of organiziing resources, for skepticism about government intervention into economic affairs, and for emphasis on the quantity theory of money as a key factor in producing inflation."

“In the economic theoretical discussion, 'Chicago' means an approach that considers economic theory to be an important tool for analyzing an alarmingly large number of concrete problems, instead of building mathematical theoretical structures of great beauty but little explanatory power; it means an approach that insists on testing general theoretical considerations and rejects both facts without theory and theory without facts. In the economic policy discussion, 'Chicago' means the conviction of the efficiency of free markets with regard to resource allocation, skepticism about state intervention in the economy and the emphasis on the quantity theory of money for inflation. "

Theory history and development

1892–1920: Early Chicago School

In its early days, it did not differ from other American business schools in terms of schooling. In the first phase, the economists Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929), Leon C. Marshall , John Maurice Clark (1884–1963), Wesley C. Mitchell (1874–1948 ) teach - attracted by the conservative dean James Laurence Laughlin (1850–1933) ), Robert Hoxie , Chester W. Wright , Simeon L. Leland , Alvin Johnson, and John U. Nef .

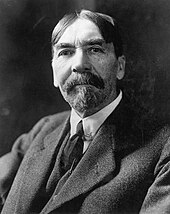

James Laurence Laughlin (1850-1933)

The University of Chicago was founded in 1892 by John D. Rockefeller . Its first president was William R. Harper (1856-1906). As a special feature, the university was given an independent faculty for political economy (Department of Political Economy). Harper initially planned to make Richard T. Ely (1854-1934) dean of the faculty. The negotiations with Ely, who was close to the German historical school , failed because of his salary demands. By chance Harper met James Laurence Laughlin , who had impressed him during a discussion in New York about monetary theory. It is anecdotal that Harper discussed with Laughlin until the early morning and finally won Laughlin as dean of the new faculty. From 1892 Laughlin published the Journal of Political Economy , which soon became one of the leading journals.

With Laughlin, Harper had chosen the exact opposite of Elys: Laughlin was deeply conservative and a staunch supporter of the classical economists : Adam Smith , David Ricardo and especially John Stuart Mill . He contemptuously called Ely's interventionist approach "elyism". On the one hand he emphasized the empirical verification of economic theory, on the other hand - as critics accused him - the classical theory seemed to be excluded from it and refuted by nothing. For him, classical theory was on a par with religious truths:

“The laws of production and their harmony worth fundamental Christian truths. […] In fact, we find […] that in our efforts to satisfy material wants, the fundamental economics principles are but statements of the form in which Christian ideas take shape. "

He published mainly on monetary theory and was, in contrast to later representatives of the Chicago School, a supporter of the central bank and was involved in the establishment of the Federal Reserve . He can be counted among the forerunners of the insider-outsider model . From an economic point of view, his work is seen as not very creative. Its main merit lies in the structure of the faculty: the decisive factor for the appointment of faculty staff was not their ideological orientation, but solely their technical excellence.

Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929)

Thorstein Veblen is one of the founders of American institutional economics . He was a staunch opponent of neoclassical theory (the word "neoclassical" probably goes back to him). Your deduction results are wrong, since the basic assumptions of neoclassical price theory are already wrong. Economics cannot exist as a separate science, but only as an overarching science that includes economics, sociology and anthropology. The fact that Veblen was appointed by Laughlin despite his sometimes biting criticism of the market economy can be seen as an example of Laughlin's undogmatic appointment practice. When Veblen had to leave Chicago after 14 years, it was not the result of his ideological attitude, but of his private life, which was perceived as extravagant: Even Laughlin's intervention could not prevent his dismissal by Harper.

John Maurice Clark (1884–1963)

After Harper's death in 1907, Harry Pratt Judson succeeded him; this gave Laughlin significantly more freedom in the appointment of faculty members: Chester W. Wright and Leon C. Marshall were among the most important appointments of this time . Marshall succeeded Laughlin as dean of the faculty after his retirement. The call of John Maurice Clarks , the son of John Bates Clarks , to Chicago in 1915 goes back to his influence and is the most important of this phase. Clark's reputation helped overcome the ossified structures of the end of the Laughlin era. Clark's economic thinking was influenced on the one hand by the neoclassical legacy of his father, but on the other hand also by the integration of institutionalist thinking: He considered an economic system based on pure laissez-faire to be impossible and recommended "cautiously following a social-liberal control" (" cautiously towards a program of social-liberal planning ") (Social Control of Business (1926)).

1920–1940: First Chicago School

The roots of an independent Chicago school go back to the 1920s. During this time, three groups can be identified within the business faculty: first the so-called hard core of the later Chicago School - consisting of the trio Frank Knight , Jacob Viner and Henry Calvert Simons . Then a second group that can be called institutionalists ; and finally a third heterogeneous group of quantitatively oriented economists.

Frank Knight (1885–1972)

In 1928 Frank Knight was offered the chair of economic theory as successor to John M. Clarks. Skeptical of all recognized doctrines, all scientific and religious dogmas and all -isms (both communism and socialism as well as capitalism), it is difficult to classify: it is assigned to the neoclassical , the Austrian school and also the institutionalists . Despite all doubts and skepticism, he saw himself as a classical liberal: he considered the classical liberalism of the 19th century to have failed (The Case for Communism: From the Standpoint of an Ex-Liberal (1932)), but its profound hindsight Skepticism towards political power in considering central economic planning to be sensible; Economic reforms and planning are fundamentally irrational ("All talk of social control is nonsense") and determined by political self-interests:

"The probability of people in power being individuals who would dislike the possession and exercise of power is on a level with the probability that an extremely tender-hearted person would get the job of whipping master in a slave plantation."

It also differed from classical liberalism in the way in which the market economy system was legitimized: For it, economic freedom was an end in itself, not just a utilitarian means of satisfying consumer wishes. The ethical justification of the market economy occupied him all his life; however, he never reached the level of optimistic conviction in the market economy that his student Milton Friedman later did in Capitalism and Freedom. He accused Friedman of gross oversimplification. From an ethical point of view, the market economy is never fair (The Ethics of Competition (1923)), but rather comparable to a game of chance:

"The luck element is so large [...] that capacity and effort may count for nothing [...] the luck element works cumulatively, as in gambling games generally."

The market economy can only be convincingly legitimized in view of its alternatives. Nevertheless, he attacked social policy almost more sharply than Friedman, since it failed to achieve the goals it had set for itself; he called communism "madness, truly criminal madness, of course; but how many of the bright and educated have fallen for and preached for it." (On the History and Method of Economics (1956), P. 273)).

Knight's best-known work is Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (1921). In it he explained how profit can still arise in a system of complete competition : He differentiates between risk and uncertainty ( Knight's uncertainty ); while risk is insurable (and therefore cannot produce a profit), real uncertainty cannot be insured and thus can be a source of profit. Gérard Debreu also sees the Arrow-Debreu model anticipated in Risk, Uncertainty and Profit .

Knight has participated in numerous landmark discussions in economics. So he attacked the capital theory of the Austrian school, which goes back to Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk . Furthermore, in Fallacies in the interpretation of social costs (1924) he took a position against Arthur Cecil Pigous welfare economics . Keynesianism never considered little more than charlatanism. According to Don Patinkin's tradition, his edition of Keynes General Theory was littered with numerous comments, one of which was 'Nonsense!' belonged to less abusive ones. Keynes had "succeeded in carrying economic thinking back to the Dark Age."

Methodologically, Knight was opposed to quantitative research; this eventually led to alienation even from his former closest students. He countered Kelvin's dictum "When you cannot measure, your knowledge is meager and unsatisfactory":

"[This saying] very largely means in practice: If you cannot measure, measure anyhow!"

He was no less dismissive of the increasing mathematization of economics. Since the social sciences are epistemologically different from the natural sciences, their methods cannot be meaningfully transferred to economics. Nevertheless, this does not make their statements any less precise and generally valid than those of the natural sciences. The rejection of quantitative methods created great tension with other faculty members such as Henry Schultz and Paul Howard Douglas , so that towards the end Knight and Douglas only communicated with each other via letters.

Jacob Viner (1892-1970)

The most important course in the economics faculty's curriculum was the - almost legendary - course economics 301, in which the advanced students intensively discussed price theory. It was always given by the most important professors in the faculty. One of them was Jacob Viner , a student Frank W. Taussig of Harvard in 1919 to Chicago (professor from 1925) came and stayed there until the 1946th He was known and feared for his sometimes even humiliating style in economics 301. His teaching style was closely related to Taussigs, but as Paul Samuelson later said: "Viner added one new ingredient: terror." For some students, however, his rough style, which lurks for student mistakes, also proved to be a performance-enhancing challenge. Evsey Domar later recalled: "To fight him back became my greatest ambition."

From a scientific point of view, Viner mainly dealt with the background to the global economic crisis . He was one of Keynes' early critics, which is surprising in that their analyzes of the Great Depression were not dissimilar. Viner saw falling profit margins as the cause, as product prices had fallen faster than costs. The only solution he saw under the gold standard was lower wages, and after it was relaxed, he also advocated raising the price level. Keyne's solutions, however, were hardly useful as general theory; his theory is only valid in the short run in absolutely exceptional situations like the world economic crisis. Viner also criticized Keynes' proposals to fight unemployment: Keynes considered wage cuts to be unsuitable for lowering them, Viner countered this:

“In a world organized in accordance with Keynes's specifications there would be a constant race between the printing press and the business agents of the trade unions, with the problem of unemployment largely solved if the printing press could maintain a constant lead and if only volume of employment, irrespective of quality, is considered important. "

Furthermore, he considered his theory about the determination of the interest rate to be wrong: It was not the liquidity preference , but supply and demand that determined its level. Viner did not consider the stability of the consumption function , as determined by Keynes , where c indicates the propensity to consume , to be mandatory: Consumption could very well turn out differently, depending on whether real wages are falling and the price level remains the same or whether real wages remain the same when the price level rises. He did not deny the value of some of Keynes' ideas for the advancement of economics, agreed with him on the post-war economic order, but considered him more of a prophet or politician of sorts. At his suggestion, despite Frank Knight's resistance, Keynes was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Chicago in 1940. Nevertheless, he summed up:

"I regard Mr. Keynes's [views] with respect to money and monetary theory in particular [...] as, figuratively speaking, passing the keys of the citadel out of the window to the Philistines hammering at the gates."

Viner's actual research focus was on foreign trade theory , price theory and the history of economics. His foreign trade theory hardly differed from that of his teacher Taussig; he was a supporter of free trade , with some restrictions on the classical theory. However, his foreign trade theory could not prevail against the Heckscher-Ohlin model . In The Customs Union Issu (1950) he was the first to work out that the creation of a customs union and free trade areas need not always have a welfare-increasing effect, since not only new trade flows would arise (trade creation) but also existing trade flows could be diverted (trade diversion): A product would then be imported more cheaply from a member country of the customs union, although it could be produced more cheaply both before and after the creation of the customs union in a third country: From a global perspective, this has a welfare-reducing effect. The model was later expanded by James Meade . His largest theoretical-historical treatise Studies in the Theory of International Trade (1937) also deals with foreign trade. For him, the classic free trade theory was based on the following four motifs: the idea of a cosmopolitan brotherhood of all people, a welfare-promoting effect, the unequal global distribution of resources and the religiously influenced hope for peaceful cooperation among all people. In his research on Adam Smith he emphasized that his Wealth of the Nations can only be fully understood in connection with the Theory of Moral Sentiments .

Aaron Director (1901-2004)

For a long time before his time in Chicago, Aaron Director had strong sympathies for socialist theories and worked, among other things, in the coal industry . He came to Chicago as a postgraduate in 1927 , where he worked as an assistant to Paul Douglas and wrote The problem of unemployment with him . Furthermore, he was one of Frank Knight's students, whose perfectionism was also a hindrance to him. The early work of this phase, prompted by the global economic crisis , dealt with the problem areas of stagnation and unemployment: Unemployment does not arise, contrary to a common belief at the time, through technical progress: it only leads to the shift of jobs within the economic sectors . To avoid unemployment in depression, he recommended state job creation measures, which should be financed by money creation instead of taxes. He considered credit expansion unsuitable for overcoming depression, as business people would not take out credit even when interest rates were low.

1937/38 spent Director at the LSE. He did not return to Chicago until 1946 as the successor to Henry Calvert Simons . In this phase, monopoly theory formed the focus of his work: He rejected the doctrine of a strong antitrust policy based on classical price theory , which was prevalent in Chicago at the time . Monopolies usually lead to increases in efficiency without actually causing the feared price increase for consumers and are mostly only temporary. The remaining, actually problematic monopolies mostly owed their existence to state intervention. Directors' monopoly theory is one of his most important contributions and can be seen as the forerunner of the law and economics movement in Chicago. Director, whose influence tended to have an indirect and catalytic effect on students, also developed the first ideas that later became known as public choice : Lobbyism would be considerably strengthened if the trust in intervention made it a point of contact for lobby groups:

"By inculcating the idea that the government must manage thing, are we not encouraging the growth of organized minority groups among workers and employers which will divide the country into warring camps?"

He found trust in state intervention and the restriction of economic freedom especially among intellectuals. The paradox that precisely those who wanted to restrict economic freedom, for whom freedom of expression and the market for ideas were most important, was explained by people's tendency to overestimate their own contributions:

"It may be asserted with some confidence that among intellectuels there is an inverse correlation between the appreciation of the merits of civil liberty — including freedom of speech — and the merits of economic freedom."

1945–1960: post-war era

Theodore W. Schultz (1902-1998)

Theodore W. Schultz , son of German farmers from South Dakota , came to Chicago in 1944, where he stayed until the end of his life. In 1979 he received the Nobel Prize for Economics . Schultz was one of the first to apply price theory to supposedly non-economic problems; thus he can be counted among the forerunners of Gary Becker. Before he came to Chicago, the focus of his work was on agricultural economics , especially with regard to developing countries . During his time in Chicago, he turned to human capital theory . He became aware of the underlying problem when he discovered that during the 1940s and 1950s the productivity of the area had increased significantly without this being explained by the use of machines and personnel. He explained this with the increased human capital :

"Man has the ability and intelligence to lessen his dependance on cropland, on traditional agriculture, and on depleting resources of energy and can reduce the real costs of producing food for the growing world population."

He contrasted this concept with the impoverishment theories, which are in the tradition of Thomas Robert Malthus ' population trap. Similarly, developing countries would improve their situation not simply by using physical capital, but above all by increasing human capital. The topics of agricultural economics, development aid and human capital are thus closely linked.

1953-1970: Chicago Boys

Based on his human capital theory, Schultz was convinced that the developing countries of Latin America could only be advanced through improved education in the fields of economics , agricultural technology , engineering, business administration and public administration. In 1953 he turned to Albion Patterson to develop an academic exchange program for South America. In 1955 Schultz, Earl Hamilton , Simon Rottenberg and Arnold Harberger traveled to Chile to sign contracts with the Universidad Católica de Chile . From 1956 to 1970 about a hundred Chilean students took part in the exchange program; the first were Sergio de Castro , Carlos Massad and Ernesto Fontaine in 1956 . Similar programs were soon set up with the support of the Ford and Rockefeller Foundation under Harberger's direction with the National University of Cuyo (Argentina), Universidad del Valle (Colombia) and many other universities across South America.

When Salvador Allende became President of Chile in September 1970 , the country experienced intensified protectionist measures, socialization and nationalization . All economists classified as anti-socialist - including those of the UCC - no longer received salaries. The now isolated economists secretly worked out a program that analyzed the economic problems of the country under Allende in Chicago-style and made suggestions for solutions; it was called El Ladrillo 'the brick': it mainly contained market economy reforms, but also health and child nutrition programs, effective social facilities and social housing.

In 1973 Augusto Pinochet took power in Chile through a military coup and established a military dictatorship. The military initially tried unsuccessfully to solve the economic problems. After this apparently remained unsuccessful, Los Chee-Ca-Go Boys , as the UCC graduates were called, were entrusted with the country's economic reform in 1975 . They included Juan Carlos Mendez (tax reforms), Sergio de la Cuadra (foreign trade), Miguel Kast (social policy) and José Piñera (social security and labor); de Castro was in charge of management.

The public perception of the Chicago Boys was and is controversial. Although the program was founded by Schultz, the actual project coordinator was H. Gregg Lewis and the intellectual father of the project Harberger, the Chicago Boys were mostly associated with Milton Friedman and accused of having Chile as his ideological laboratory. Juan Gabriel Valdés saw in “economic reductionism” and the “prejudice against politics” the attractiveness of the Chicago School for non-democratic regimes.

D. Gale Johnson (1916-2003)

Another important exponent of the agro-economic branch in Chicago was D. Gale Johnson , whom Schultz had brought from Iowa. He received a professorship in Chicago in 1954 and also took on several faculty administration tasks. In particular, he examined the agricultural sector in centrally administered economies and gave them a pathetic testimony:

"The deaths that can be attributed to socialized agriculture as, for example, in Stalin's Soviet Union and Mao's China, may well equal those of World War II, including Hitler's attempts at extermination of Jews an others."

He developed an overall demand function of the agricultural sector, a preliminary stage of the work of Zvi Griliches and Marc Nerlove .

1960–1970: Second Chicago School

The Chicago School was mentioned for the first time at a time when retirement, deaths and removals significantly weakened the faculty, and Milton Friedman from Columbia University was just returning to Chicago as a professor (1946). In addition, it can be assumed that Friedman, who was “only” in second place on the list of appointments, tried particularly hard to build up his own reputation. Friedman is now the most famous representative of the Chicago School.

Milton Friedman (1912-2006)

Milton Friedman himself studied in 1932 on the recommendation of Arthur F. Burns in Chicago with Knight, Viner, Simons, Lloyd Mints, Douglas and Schultz. A circle developed from the interplay between Frank Knight and Jacob Viner , whose most important members included Friedman, his later wife Rose Director , George Stigler , Allen Wallis and the younger lecturers Aaron Director and Henry Simons. The intensive exchange around the charismatic teacher Frank Knight allowed the group to develop into the nucleus of its own direction within the faculty. Friedman returned to Chicago in 1946 as a professor.

In terms of method, Friedman differed significantly from the other faculty members: Complex mathematical models on an econometric basis did not seem useful to him. He was in constant tension with the members of the Cowles Commission . His own methodological model was based less on profound philosophical considerations than it emerged in the course of his research work, as it were as a by-product: He preferred simple mathematical models with simplifying basic assumptions, which, however, had to be empirically verified by their predictive power (The Methodology of Positive Economics (1952 )).

One of his most influential early scientific discoveries was the permanent income hypothesis (The Theory of the Consumption Function (1937)); Simon Smith Kuznets found in 1936 that - contrary to the conclusions of the Keynesian absolute income hypothesis - the savings rate in the USA had not increased over a period of thirty years. Friedman explained this paradox by saying that a person's consumption does not depend on their current income, but on their average permanent income. Franco Modigliani developed this into the life cycle hypothesis. The velocity of circulation of money can in turn be represented as a function of permanent income, as Friedman found confirmed by empirical studies. Friedman's theory of the Phillips curve was also developed in a confrontation with Keynesianism . With the assumption that this would run vertically in the long term, he saw himself confirmed by the stagflation of the 1970s. Unemployment cannot be reduced by inflation, but only by removing market restrictions (see natural unemployment rate ). In 1976 Friedman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics “for his contribution to consumption analysis, monetary history and theory, and his clarification of the complexity of stabilization policy”.

Friedman became known to the public more for his polarizing political activity than for his academic work. He was an enthusiastic supporter of free markets, which led Times columnist Leonard Silk to refer to him as "Adam Smith's most distinguished spiritual son". He defended the right to bring up parents, which he wanted to strengthen with education vouchers , and called for the abolition of compulsory military service . State transfer payments and minimum wages would not be in the interests of their recipients, but increased poverty; as an alternative, he proposed a negative income tax . He himself made it a point to judge his scientific work independently of his political positions, even if they did not remain unaffected by his economic knowledge. George Stigler commented:

"His de facto presidency of the unorganized Friends of Private Enterprise has not endeared him to the majority of professional economics [...] Friedman's role [...] would be viewed a good deal more sympathetically by economists if only he did it less well."

Since 1970: Third Chicago School

The third Chicago School includes, in addition to the continuation of Friedman's monetarism, James M. Buchanan , Robert E. Lucas , Robert Fogel , Gary S. Becker , Richard Posner and Eugene Fama .

Gary Becker (1930-2014)

Economics 301 was given by Friedman until 1976. He was succeeded by Gary Becker, who would keep the course for the next 20 years. He is best known for analyzing diverse phenomena outside of the actual field of economics using price theory. In his dissertation The economics of discrimination (1957) he made a contribution to the application of economic theory to hostilities against social minorities by applying a simple foreign trade model: suction. Discrimination coefficients worked like import tariffs. In some cases, the work received little favorable reviews, and the then completely new transfer of the materialistic economic model to ethical issues was criticized; Chicago University Press only printed the book after Stigler intervened.

Becker's magnum opus, Human Capital, appeared when Becker had moved to Columbia University in 1957. His central thesis is that education and training as well as health can be explained in the same way as any other investment by looking at the return on investment . In Human Capital he also attacked the then prevailing Pigouvian thesis that training and further training of their external effects had to be carried out by the state: Since companies with further training of their employees would always fear that they would be lured away by other companies, there would be no incentive for them To train employees. Becker differentiates between company-specific and general human capital: Since company employees benefit fully from training measures in the form of a higher salary, there would be enough incentive for them to bear the costs of training themselves. This distinction also explains the income gap between men and women: since women are more likely to take off work or work part-time due to pregnancy, they are less incentivized to invest in their human capital. This could also explain the Leontief paradox , since human capital is not taken into account in the underlying econometric studies. Of particular political relevance was his finding that there was a connection between ethnic groups and their average income or their position in company hierarchies: Japanese, Chinese, Jewish and Cuban families are statistically small, which leads to high investments in their children and high incomes, whereas Mexicans, Puerto Ricans and Afro-Americans have statistically large families, which leads to little investment in the human capital of the children and who later have low incomes due to poor education.

Eugene Fama (* 1939)

Eugene Fama is the Robert R. McCormick Distinguished Service Professor of Finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business . He is particularly known for his work on the market efficiency hypothesis . He also examines the empirical relationship between risk and expected return and its consequences for portfolio management . He is considered the father of modern finance and is quoted many times. Judging by his citations, he is the ninth most influential economist of all time. In 2013, Eugene Fama, together with Robert J. Shiller and Lars Peter Hansen, was awarded the Alfred Nobel Memorial Prize for Economics for their work on the efficiency of markets (or “for their empirical analysis of asset prices”) .

The market efficiency hypothesis states that asset prices reflect all available information. A direct consequence is that no market participant can beat the market in the long term. Prices should only respond to new information and should therefore show a random walk.

In addition, Fama and Kenneth French took a critical look at the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM). The CAPM states that the average return on an asset is explained solely by its beta . Eugene Fama and Kenneth French were able to show that there are other independent risk factors that determine the expected return. These factors are Size and Value. This means the systematic excess return of small companies (size), or companies valued cheaply, relative to a fundamental company parameter (value). Fama and French therefore introduced a three-factor model , which explains equity loans using 3 statistically independent risk factors.

Richard Posner (* 1939)

Posner is a member of the law faculty; He acquired his economic knowledge in self-study. He is considered to be one of the founders of the law and economics movement, which deals with the economic analysis of law . He sees this justified by the close connection between justice and economic efficiency:

"[The central] meaning of justice — perhaps the most common is — efficiency ... [because] in a world of scarce resources waste should be regarded as immoral."

Steven Levitt (* 1967)

Levitt is a professor at the University of Chicago and director of the Becker Center on Price Theory there. He is also a holder of the John Bates Clark Medal .

He became famous for an article "The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime" published in 2000 (together with John Donohue III), in which he used multivariate statistical methods for the USA to establish a connection between the legalization of abortion in the mid-1970s and showed the decline in the crime rate in the early 1990s. The reason for the observation is: the legalization of abortion also gave those women the opportunity to have an abortion who could not offer their children a stable home, for example because they were addicted to drugs or lived in a criminal environment. Children from such homes are more likely to become criminals. The decline in the US crime rate in the 1990s thus came about when that generation would have come of age. Levitt emphasizes that he does not see this connection as a justification for abortion. With his popular science books Freakonomics: Surprising Answers to Everyday Questions of Life and the successor SuperFreakonomics - Nothing is as it seems: About Earth's cooling, patriotic prostitutes and suicide bombers with life insurance , he is one of the most controversial economists in the US today.

literature

Primary literature

Collective works:

- Ross B. Emmett (Ed.): The Chicago Tradition in Economics, 1892-1945 . 8 volumes. Routledge, London / New York 2002, ISBN 978-0-415-25422-9 .

Early Chicago School:

- Thorstein Veblen: The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions . BW Huebsch, New York 1918 ( oll.libertyfund.org - first edition: 1899).

- James Laurence Laughlin: From American Economic Life (Lectures in Berlin 1906) . GB Teubner, Leipzig 1907 ( archive.org ).

First Chicago School:

- Frank H. Knight: Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit . Hart, Schaffner and Marx, Boston MA 1912 ( oll.libertyfund.org ).

Second Chicago School:

- J. Daniel Hammond and Claire H. Hammond (eds.): Making Chicago Price Theory: Friedman-Stigler Correspondence 1945–1958 . Routledge, London / New York 2005, ISBN 0-415-70078-7 .

Third Chicago School:

- Gary Becker : Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education . 3. Edition. University of Chicago Press, Chicago 1994, ISBN 0-226-04120-4 (first edition: 1964).

- Gary Becker : The Economic Approach to Explaining Human Behavior . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1993, ISBN 3-16-146046-4 (Original title: The Economic Approach to Human Behavior (1976) .).

Magazines:

- Journal of Political Economy . ISSN 0022-3808 ( journals.uchicago.edu ).

- The Journal of Law and Economics . ISSN 0022-2186 ( journals.uchicago.edu ).

Secondary literature

- Ross B. Emmet: Chicago School (new perspectives) . In: Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume (Eds.): The New Palgrave - Dictionary of Economics . 2nd Edition. tape 1 . Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, pp. 765-769 .

- Ross B. Emmett: Frank Knight and the Chicago school in American economics ( Routledge studies in the history of economics . Volume 98 ). Routledge, London / New York 2009, ISBN 978-0-203-88174-3 .

- Warren S. Gramm: Chicago Economics: From Individualism True to Individualism False . In: Journal of Economic Issues . tape 9 , no. 4 , 1975, p. 753-775 .

- John P. Henderson: The History of Thought in the Development of the Chicago Paradigm . In: Journal of Economic Issues . tape 10 , no. 1 , 1976, p. 127-147 .

- Eva Hirsch and Abraham Hirsch: The Heterodox Methodology of Two Chicago Economists . In: Journal of Economic Issues . tape 9 , no. 4 , 1975, p. 645-664 .

- John McKinney: Frank H. Knight and Chicago Libertarianism . In: Journal of Economic Issues . tape 9 , no. 4 , 1975, p. 777-799 .

- H. Laurence Miller, Jr .: On the "Chicago School of Economics" . In: The Journal of Political Economy . tape 70 , no. 1 , 1962, pp. 64–69 (The article was the first to postulate the existence of an independent Chicago School and was denied by George Stigler in the same issue).

- Claus Noppeney: Between the Chicago School and Ordoliberalism . Paul Haupt, Bern / Stuttgart 1998, OCLC 716717797 .

- Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 .

- Don Patinkin: Keynes and Chicago . In: Journal of Law and Economics . tape 22 , no. 2 , 1979, p. 213-232 .

- Melvin W. Reder: Chicago Economics: Permanence and Change . In: Journal of Economic Literature . tape 20 , no. 1 , 1982, pp. 1-38 .

- Melvin W. Reder: Chicago School . In: Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume (Eds.): The New Palgrave - Dictionary of Economics . 2nd Edition. Vol. 1. Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, pp. 760-765 .

- Warren J. Samuels: Introduction: The Chicago School of Political Economy . In: Journal of Economic Issues . tape 9 , no. 4 , 1975, p. 585-604 .

- Warren J. Samuels: The Chicago School of Political Economy . Association for Evolutionary Economics, 1976, ISBN 0-87744-140-5 .

- Mark Skousen : Vienna & Chicago, friends or foes ?: a tale of two schools of free-market economics . Capital Press, Washington 2005, ISBN 0-89526-029-8 (A treatise on the ambivalent relationship to the Austrian School ).

- George J. Stigler: On the Chicago School of Economics: Comment . In: The Journal of Political Economy . tape 70 , no. 1 , 1962, pp. 70-71 .

- Juan Gabriel Valdes: Pinochet's Economists: The Chicago School of Economics in Chile . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-06440-8 .

- Rob Van Horn, Philip Mirowski : The Rise of the Chicago School of Economics and the Birth of Neoliberalism . In: Philip Mirowski, Dieter Plehwe (eds.): The Road from Mont Pèlerin. The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective . Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass./London 2009, pp. 139-178.

- Charles K. Wilber, Jon D. Wisman: The Chicago School: Positivism or Ideal Type . In: Journal of Economic Issues . tape 9 , no. 4 , 1975, p. 665-679 .

Web links

- Official website of the University of Chicago - Department of Economics

- The New School's Chicago School website

- History of The New School for Social Research

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: How the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 1-17 .

- ^ Melvin W. Reder: Chicago School . In: Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume (Eds.): The New Palgrave - Dictionary of Economics . 2nd Edition. tape 1 . Palgrave Macmillan, New York 2008, pp. 760-765 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , Chapter 2 — Chicago's Pioneers. The Founding Fathers, S. 45-74 .

- ↑ Quoted from Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 48 .

- ^ Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 87 .

- ^ A b c d Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 79-90 .

- ^ Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 110-113 .

- ^ A b c d Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 348-353 .

- ^ Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 10 .

- ^ Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 113-115 .

- ^ A b c d Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: how the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 90-108 .

- ^ A b Johan van Overtveldt: The Chicago School: How the University of Chicago assembled the thinkers who revolutionized economics and business . Agate, Chicago 2007, ISBN 978-1-932841-14-5 , pp. 121-124 .

- ↑ a b c d Eugene F Fama. Retrieved August 1, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Economist Rankings | IDEAS / RePEc. Retrieved August 1, 2020 .

- ^ A b c Eugene F. Fama: Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work . In: The Journal of Finance . tape 25 , no. 2 , May 1970, ISSN 0022-1082 , pp. 383 , doi : 10.2307 / 2325486 .

- ^ A b c d Eugene F. Fama, Kenneth R. French: Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds . In: Journal of Financial Economics . tape 33 , no. 1 , February 1993, p. 3-56 , doi : 10.1016 / 0304-405X (93) 90023-5 .