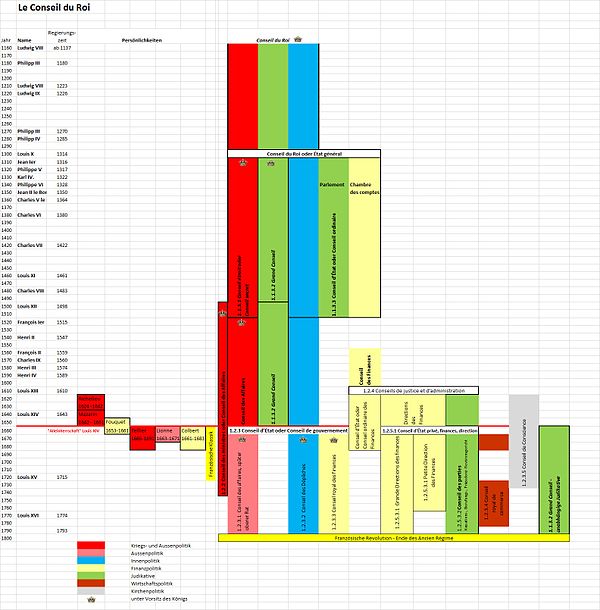

Conseil du Roi

The Conseil du Roi can best be translated as Royal Council . Under the Ancien Régime, it formed a state body that had the task of preparing state affairs for the king and advising him.

The kings of France were accustomed always been their before important decisions court to ask that the familia was called. In the 12th century, an advisory body, the Council, appears in the royal records .

The Conseil was a permanent body and the main instrument for governing the Capetian government . The king could summon subjects to the council at will to support him in his decisions. At the same time it was the duty of every subject to heed the call and advise the king, be it individually or as a body. This was especially true for the nobility and the crown vassals .

The conduct of government affairs with the help of advisors is an essential characteristic of the French monarchy . In 1302 King Philip the Fair introduced the État général (Council of State), in which clergy, nobility and citizens were represented and formed the permanent institution of the Conseil du Roi .

11th to 16th centuries

Composition and development of the Council

The composition of the Conseil changed constantly, according to the wishes and will of the King. The strengthening of the Conseil du Roi leadership instrument had various effects:

- the queen, be it the reigning queen or the queen mother, lost all political influence in France from the 13th century, except during the king's minority period. As a rule, she is not a member of the council .

- the kings exclude their close relatives, including sons, grandchildren and other possible heirs to the throne, from the council in order to avoid their influence and intrigue.

- on the other hand, the Dauphin usually becomes a member of the council as soon as he has reached the appropriate age.

- the members of the council - lay people and clergy - are more and more frequently called up and questioned, with the instrument of the council having different degrees of importance depending on the ruler. Kings Louis X (1314–1316), Philippe VI (1328–1350), Jean II le Bon (1350–1364) and Charles VI (1380–1422) relied particularly on the Conseil , while Charles V le Sage ( 1364–1380), Louis XI (1461–1483), François I he (1515–1547) increasingly withdrew from his influence. François is also considered to be the actual founder of absolutism . In the 16th century, more and more members were appointed to the council who could prove their abilities: feudal lords, church dignitaries and court officials.

- the members of the Conseil , for their part, increasingly sought advice from Légistes , that is, from lawyers who had studied Roman law . These were mainly trained at the Sorbonne , and many of them came from the lower nobility and the bourgeoisie . Given the increasing complexity of business, these Légistes made an important contribution to the preparation of business. They also ensured a certain continuity within the constantly changing council . They ultimately formed the framework within the Conseil , guaranteed the rule of law and security in decision-making. Since the reign of Henri III (1574–1589) they were called Conseiller d'État and were supported by Maîtres des requêtes .

In difficult times the rulers tended to increase the council ; at the time of Charles IX (1560–1574) and especially during the Huguenot Wars, it consisted of around a hundred members. In order to increase the efficiency of the committee again, the following kings reduced the number, or only convened parts of the council (the councils restreints).

Competencies and tasks of the council

The council only had an advisory role, the decision ultimately always rests with the king. Even after the influence of the Légistes grew - especially in the 16th century - the king was not bound by the decisions and advice of the council . He often entrusted the enforcement of unpopular decisions to his Conseillers du Conseil du Roi , the members of the royal council.

The convening of the council was not specifically regulated, but could be done for all more or less important questions, both in times of war and in times of peace. In the presence of his council , the king received the ambassadors, signed contracts, appointed responsible persons and gave them orders and orders (French: mandement) and drafted ordinances and royal edicts (French: ordonnance royale). The Conseil also acted as the Supreme Court, to which the royal judiciary turned for questions which the king reserved for decision or which had to be decided in his presence.

The meetings of the Conseil were irregular at the beginning, but became increasingly frequent until they were held daily in the mid-15th century.

The structure of the Conseil

Basically the council formed a unit, it had to give its opinion on all questions, be it finances, justice, administration. The increasing business load and its complexity made it necessary to form areas of responsibility that were dealt with by committees.

From the 13th century onwards, there were different structures: a Conseil étroit or Conseil secret (privy councilor), which consisted of only a few members, a Grand Conseil (high council), which was somewhat more extensive. The entire body with all its members became the Conseil ordinaire or Conseil d'État (Council of State), which, however, lost its reputation and importance. The king took part in his meetings only irregularly, these were usually under the direction of the chancelier and the council consisted of 50 to 60 members.

Philip the Handsome organized the Conseil du Roi and assigned competencies to the individual parts: The Grand Conseil (High Council) was responsible for political questions and was also the highest court, the Parlement was responsible for the administration of justice and the Chambre des comptes (Court of Auditors) for the Responsible for overseeing the royal finances.

Conseil secret (privy councilor)

Political questions were decided by this council, which consisted of only a few statesmen appointed by the king. But even with this concentration on a few important tasks, it became necessary to create an additional structure. King François I , he therefore created a Conseil des Affaires (Council of State Affairs), consisting of the Chancellor of France , the Secrétaire de commandements was (now Secretary of State) and a few statesmen. This advisory body gave its opinion on general politics, diplomacy and war issues.

This council dealt exclusively with political questions and can be described as the Council of Ministers , in addition it acted as a court of appeal .

Grand Conseil (High Councilor)

Under Charles VII (1422–1461) a further subgroup was created that was responsible for disputes. On the orders of Charles VIII (1483–1498), a Grand Conseil (high council) was created in 1497 , which acted as the actual court of law in great independence. It is made up of experts who had to deal with all disputes that were brought before the king. As a matter of principle, the King himself did not take part in these deliberations. Louis XII (1498-1515) confirmed this institution.

In the sixteenth century the Grand Conseil had completely separated from the person of the king and had become an independent court of justice. Certain complaints could be brought directly to the Grand Conseil . The processes were conducted in separate negotiations. Theoretically, the king and his advisors should find justice here, but in practice the chancelier presided. The trials were conducted by lawyers, the presidents of the Parlement of Paris , the Maîtres des requêtes as legal assistants, the prosecutors and defenders of the parties to the dispute who were not present themselves.

The consequence of this independence was that later a judicial department had to be created in the Conseil d'État : the Conseil privé or Conseil des Parties (party council).

Conseil d'État (Council of State)

The Conseil d'État consisted of four sections, the organization of which goes back to Cardinal Richelieu : On the one hand, the Conseil des Parties , as a result of the independence of the Grand Conseil . It acted as a court of cassation , court of appeal , sets the law of precedence and mediates in church claims and in particular disputes between the Catholic and Protestant churches. In addition there was a finance department and a department for domestic policy (French: Conseil des Dépêches).

From 1560 another department was added, the Conseil des finances (Finance Council), which later became the Conseil d'État et des finances .

French classic

Between 1661 and the revolution , power remained shared between the Conseil du Roi , which had around 130 members, and a small group of ministers and state secretaries .

The most important departments of the Conseil du Roi were presided over by the king, the monarch listened to the opinions and often followed the opinion of the majority. After Saint Simon - an energetic critic . Louis XIV , the Sun King (1643-1715), acted he himself only six times against the opinion of his Council .

Uniformity of the council, complexity of the structure

Since the 16th century, the Conseil du Roi has been divided more and more. There were three major departments: government, finance, and justice. However, these in turn consisted of subdivisions and commissions. All decisions of the council were published in the name of the king , but with different formulations, depending on whether the king was present during the decision - or whether a committee had made a decision in the king's absence.

Committee of Ministers

The meetings of the council were prepared in the ministerial departments and then discussed with the ministers. The method increasingly prevailed that business was dealt with by the ministers in the king's absence. These meetings took place weekly.

Louis XV (1715–1774) became aware of the risk involved in these cabinet meetings and forbade 1747 meetings that had not been convened by himself. Since then, the meetings of the ministers have been considerably less numerous.

Conseils de gouvernement (Government Council)

The business of the Conseil de gouvernement was always and exclusively conducted in the presence and presidency of the King. The resolutions were initiated with en commandement (when an order is issued ...). The sessions took place in the king's living quarters, in a cabinet du Conseil room that was present in all of the king's castles. The participants were convened by the cabinet ministers . Once the participants were gathered, the door was locked and guarded to prevent unfamiliar ears from overhearing the secret resolutions.

The councils gathered around a long table, the king was sitting in an armchair on one narrow side, the other participants on folding stools. The Conseil de gouvernement followed the king everywhere on his travels, which was also expressed by the appropriate seating.

The king opened the session by asking a question or allowing a speaker to speak. Everyone present had their say, in ascending order of rank. Everyone could then make their recommendation in the same order. The king finally decided at his own discretion. The Sun King rarely stuck to the advice of his council , Louis XV used the discussion abort when his opinion developed after in the wrong direction. The length of the meetings varied widely, rarely less than two hours, but depending on the agenda, the meetings could last much longer.

Conseil des affaires (Council for State Affairs)

This body was called the Conseil d'en haut (Superior Council) from 1643 , simply because the body met in the Palace of Versailles in the cabinet room on the first floor, next to the king's room.

Since the 16th century, the upper council remained the most important governing body under the Sun King , in which the king assembled his closest advisers and made the most important decisions. This institution was the forerunner of today's Conseil des ministres .

It was a very small body in which only the most important statesmen were represented: In addition to the King of Chancelers , the Surintendant des Finances , a State Secretary and ministers appointed by the King . The powers of attorney were very far-reaching, almost unlimited. With the beginning of the reign of the Sun King , the number of members initially increased, with family members, princes, dukes and pairs taking part.

1661 An amendment to a, after the death of Cardinal Mazarin made Louis XIV the government to which power was concentrated in and dismissed the majority of the members of the Upper Council. He left Tellier as Secretary of War, Lionne as Secretary of State and Colbert as Secretary of the Treasury. He later expanded to five ministers, Louis XV to seven and Louis XVI to eight. Nobody was entitled to a seat on the council , not even the Dauphin . Under Louis XV , the body was generally called the Conseil d'État (Council of State) and was in particular responsible for foreign policy, the navy and the army, and in wartime for military operations and strategic decisions. In addition, the Conseil des Dépêches was responsible for domestic policy.

The Conseil d'État met on Sundays and Wednesdays, but extraordinary meetings were often called, especially during wartime. Around 120 to 130 meetings were held each year.

The Conseil des Dépêches (Council for Home Affairs)

This council was responsible for general administrative matters. It dealt with matters presented by dispatch from provincial governors and directors.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Chancelier had presided over this council, from 1661 the king himself took over the presidency. It consisted of ten to twelve members, the Dauphin , the Chancelier , the State Ministers, State Secretaries and the Contrôleur général des finances (financial controller). Councilors of State and Maîtres des requêtes often reported on matters that were brought to them.

At the beginning the council met twice a week, under the Sun King there were fewer and fewer, as he preferred to work with his ministers. Its decisions were published as decrees, even without the consent of the Conseil . Under Louis XV , the interior affairs council became more active again and ultimately formed an equal body to the senior interior affairs council. It met on Saturdays, sometimes more often or for several days in times of crisis. The meeting days were around 50, sometimes even 70, per year.

The Conseil royal des finances (royal finance council)

This council was created in September 1661 by Louis XIV to assist him as Surintendant des Finances . The king took over this function personally after he had removed Nicolas Fouquet from his office. The powers of the council were very extensive and concerned the budget , taxation , industry, trade, money , and the contracts with the Ferme générale . The council set the tax rate, drew up the budget, approved payments, and ruled on financial disputes.

Represented on the council were the King, the Chief of the Conseil des finances (a rather representative office ... but very well paid), the Dauphin , sometimes the Chancelier , the Contrôleur général des finances (General Controller of Finances), usually two Councilors of State and the Finance directors. The council met twice a week until 1715, but soon the king was in the habit of making his decisions in consultation with the Contrôleur général des finances , without the council having been asked for its opinion.

Under Louis XV , the council met again every Tuesday, from 1728–1730 the rhythm slowed down again, and in the middle of the 18th century it met once a month. This was due to the fact that the General Controller of Finance was the only speaker. He had prepared the business with his co-workers and the other members never had the perspective and information level to be able to have any real influence.

The Conseil royal de commerce (royal business council)

This was created in 1664 to aid the royal finance council, but disappeared in 1676, to reappear around 1730. It was never as important as other parts of the Conseil du Roi and was finally incorporated into the royal finance council in 1787.

The Conseil de Conscience (Council of Conscience)

Richelieu had wanted it to be created and it appeared under the government of Anne d'Autriche (1615–1643). His job was to distribute the proceeds from church goods. Under the Régence and the Polysynodie (replacement of ministers by committees each with a chairman) it became superfluous and disappeared in 1718. Philipp d'Orléans re- created it in 1720 to enforce the measures of the papal bull Unigenitus Dei filius . In 1723 the council met every Thursday, after 1730 it lost its importance again and disappeared in 1733. It consisted only of the king, a few cardinals and bishops, but not of ministers.

The Conseils de justice et d'administration (Council for Justice and Administration)

The areas of the Conseil du Roi that dealt primarily with disputes were usually presided over by the Chancelier de France . The king never appeared, but all orders were made in his name. It was said that the Chancelier was the king's mouth .

In 1661 the Council for Justice and Administration consisted of four departments:

- Conseil d'État privé or Conseil des Parties (party council)

- Conseil d'État et des Finances or Conseil ordinaire des Finances (Finance Council)

- Grande Direction des Finances (upper finance directorate)

- Petite Direction des Finances (lower finance directorate)

The Conseils de finances (finance departments)

The Conseil d'État et des Finances or Conseil ordinaire des Finances (Finance Council)

This department of the Conseil du Roi was created at the beginning of the 17th century and had general government tasks, but also took care of the financial directorates. During the reign of Louis XIII (1610–1643) it lost its importance and only served as a supreme court in administrative disputes and as a court of cassation for decrees of subordinate, independent institutions in the field of finance. It was composed in the same way as the party council, but the Contôleur général des finances played a prominent role. In 1665 the decline of this council began to appear, between 1680 and 1690 it disappeared completely. Colbert was able to easily play off the maîtres des requêtes against the finance directors, who increasingly felt themselves to be independent councilors and issued their own instructions.

The Directions des Finances (upper and lower finance directorate)

These departments were created in 1615 and were responsible for all financial areas under Louis XIII . When Louis XIV took over financial powers , these departments disappeared in 1661.

The Conseil d'État privé or Conseil des Parties (party council)

Before the absolutist rule of Louis XIV , this department was exclusively responsible for legal questions. Towards the end of the 17th century he also took on the task of resolving disputes in the administrative and financial area, since the responsible departments had disappeared. The new Conseil d'État privé, finances et direction consisted of three departments: Conseil des Parties , the major and minor Direction des finances .

The Conseil des Parties (party council)

This council only dealt with legal disputes. He acted as the Supreme Court for private individuals in the field of civil and criminal law. He was an arbitrator in disputes between independent authorities or between courts of different instances. It acted as a court of appeals and cassation, but also carried out revision hearings for criminal offenses.

The presence of the king was the great exception ( Louis XIV participated a few times at the beginning, Louis XV was only present once in 1762 and 1766). The king's armchair, however, was always in the room to symbolize his presence. The chairman of the council was the chancelier , who sat to the right of the royal chair.

The party council was formally composed of: the heirs to the throne, the dukes and pairs, the ministers of state and state secretaries, the contrôleur général des finances , the 30 councilors, the 80 finance directors and the maîtres des requêtes . In fact, only the councils of state and the maîtres des requêtes took part regularly, and sometimes finance directors. Around 40 members were present at a time, sometimes 60.

The council met on Mondays in a dedicated council chamber in the royal residences but outside the king's apartment. In Versailles it was on the ground floor between the marble court and the prince's court. The councilors of state sat on armchairs upholstered in saffiano leather, and the maîtres des requêtes had to stand. After the negotiations, the chancelier invited the gentlemen of the council to dinner.

The party council has holidays from October to Martini , holds between 40 and 45 meetings a year and passed 350 to 400 judgments. Before the negotiations, the business was prepared by councilors of state and maîtres des requêtes . For this purpose, there were various sub-commissions that prepared the business of the various areas: church affairs, appeals, cassations. Since the judgments were usually not substantiated, the party council usually first asked the subordinate authority to give reasons for the judgment.

The big and small Direction des finances (Finance Directorate)

These two commissions took over the tasks of the Conseil d'État et des finances for disputes in financial matters. The large finance directorate only met 6 to 12 times a year, the small directorate comprised around ten people, had to prepare the business for the large finance directorate and made decisions on simple matters itself. It met irregularly and disappeared in 1767. The directorates consisted of councilors of state and maîtres des requêtes , the large finance directorate was under the direction of the Chancelier de France.

See also

bibliography

- Adolphe Chéruel: Dictionnaire historique des institutions, mœurs et coutumes de la France. L. Hachette et cie, 1855 ( online ).

- Michel Antoine: Le Conseil du roi sous le règne de Louis XV. Droz, Paris / Geneva 1970. New edition, Droz, Geneva 2009.

- Bernard Barbiche: Les institutions françaises de la monarchie française à l'époque moderne. Presses universitaires de France, Paris 1999.

- Christophe Blanquie: Les institutions de la France des Bourbons (1589–1789). Belin, Paris 2003.

- François Bluche: L'Ancien Régime. Institutions et société. Paris 1993, ISBN 2-25306-423-8 .

- Pierre-Roger Gaussin: Les conseillers de Charles VII (1418-1461). Essai de politologie historique. In: Francia , number 10, 1982, pp. 67-130 ( online ).

- Jean-Louis Harouel and others: Histoire des institutions de l'époque franque à la Révolution. Presses universitaires de France, Paris 1996.

- Roland Mousnier: Le Conseil du Roi de Louis XII à la Révolution. Presses universitaires de France, Paris 1970, 378 ( online ).

- Noël Valois: Le Conseil du roi et le Grand Conseil pendant la première année du règne de Charles VIII. In: Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes. 1882 ( PDF download ).

- Noël Valois: Étude historique sur le conseil du roi. Introduction à l'inventaire des arrêts du conseil d'État. Imprimerie nationale, Paris 1886 ( online ).

- Noël Valois: Le Conseil du roi aux XIVe, XVe et XVIe siècles, nouvelles recherches, suivies d'arrêts et de procès-verbaux du Conseil. Paris 1888, X-401 ( PDF download ).