The blacksmith from Göschenen

The Schmied von Göschenen is a historical novel by Robert Schedler . The work, published for the first time in 1919, tells the legend of the construction of the first path through the Schöllenen Gorge and thus of making the Gotthard Pass clear . It is considered a classic of Swiss literature for young people and was printed in eleven editions (48,000 copies) by 1971. The original pen drawings were by Theodor Barth , newer editions are provided with illustrations by Felix Hoffmann .

action

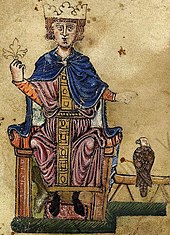

The story begins in Hospental at the foot of the Gotthard Pass. King Friedrich II is at war with King Otto IV . It is the autumn of 1212, twenty-three years after the crusade of Frederick Barbarossa . Frederick II arrives in Hospental with his cavalry army from Milan and asks for hospitality in the castle there. After confirming his peaceful intent, he is allowed in. He intends to ride to Basel as soon as possible to win the city over and prevent it from opening the gates to his opponent Otto. Unfortunately there is no way through the Schöllenen and the only alternative, the detour over the Bäzberg, can only be done on foot. The only paths from Hospental that can be traversed with an army lead over the Oberalp Pass or the Furka and the Grimsel to the north. On the advice of Heinrich von Sax, Friedrich decides to take the route across the Oberalp, because it is the most suitable for a cavalry army and he expects additional support on his way. As a result, however, he loses five to six days and, if he comes to Basel too late, his crown too. A letter carried by a spy who happened to be blown up confirms the danger to the king.

Heini, a fourteen-year-old boy from Göschenen , serf of the Counts of Rapperswil, is a goatherd from Uri and knows the arduous route over the Bäzberg to Flüelen. He offers the knights to bring the news of Friedrich's imminent arrival by direct route via Lucerne to Basel. Berardus de Castanea, Archbishop of Bari , who is traveling with Friedrich, wrote a short note to his friend Lüthold von Aarburg , Bishop of Basel. When night falls, Heini sets out and crosses the Bäzberg. At dawn he reached Flüelen, where he drove on a Nauen over Lake Lucerne to Lucerne .

Heini sets out from Lucerne via Rothenburg to Olten . On the way he tries to march in secret as well as possible, because the Zähringers are not well-disposed towards Friedrich from Staufer. Should his mission be exposed, not only would the assignment be forfeited, but his life too. He spends the next night in Olten before conquering the Untere Hauenstein . In Läufelfingen he learns that the Staufer's cause in Basel is considered lost because he is being held prisoner in Milan and Otto the Welf is on the march towards Lake Constance . However, Heini is silent.

In Basel, Heini was immediately admitted to the bishop, who was delighted with the news. He immediately convenes the chapter of the monastery and a meeting of the guild masters . The bishop urgently recommends the assembly to take the side of Frederick, since Otto of Pope Innocent III. is subject to a curse and this would spread to the city if they join him.

During the few days that Heini spends in Basel as the bishop's guest, he begins to be interested in the blacksmith's trade . For a long time he marveled at the construction work on Basel Minster . Unfortunately, as a serf, he cannot decide for himself what he will learn and become. When the king then arrives in Basel and is amazed to see that Heini has marched from Göschenen to Basel in just three days, he is impressed and promises to buy him out of the serfdom of the Counts of Rapperswil. The king's further words will occupy him for a long time: “Who could make this path passable for my horse and team! The best connection between Basel and Milan! I would make him a prince. But this is purely impossible; the granite wall in the Schöllenen is invincible. I saw that myself. Man can do nothing against nature. "

A few days later Heini returns to Göschenen. From now on his goal is to conquer the Schöllenen. He thinks about how to avoid the big rock that blocks the way. He remembers the construction workers he saw working with cranes at the cathedral in Basel. This gives him the idea of creating a "hanging" path. He builds an experiment with ropes with beams hanging at the lower end over the boards. The attempt is successful, but in order to be able to realize his project, he has to learn to forge chains , because ropes are too weak and not durable enough. But the king has forgotten his promise, and when Heini wants to ask the Vogt about it, the latter becomes grumpy and dismissive. He is not interested in the fact that only one major change could save the poor mountain farmers, whose soil has long been barely enough to feed themselves, from misery. And the peasant people certainly don't need a blacksmith who could also make weapons! Instead, Heini is sold to the Sankt Urban monastery .

On the way to the abbey, which Heini travels with five boys of about the same age accompanied by a knight, he learns that it could have been worse: the knights are looking for children all over Europe for the children's crusade .

Major construction work is in progress in the monastery, and the boys have been acquired to carry it out. Heini is assigned to the brick burning. Soon he met the foreman, a strange monk whose origins remained in the dark. Heini learns from him how the bridge over the Reuss is to be built during non-working hours . Heini manages to save enough from his wages so that, on the recommendation of the foreman at the abbot, he can finally buy the freedom he longed for after four years.

After saying goodbye to the monastery, Heini moves to Bern on the advice of the foreman . The young, thriving city promises plenty of work. The city was founded by the Zähringers only 26 years ago , their last representative is Berthold V , whose death in 1218 will lead to the expansion of power of the Habsburgs. Heini immediately goes to the forge's guild master and brings up his request. According to the guild rules, he has to do an apprenticeship with a blacksmith for three years.

In the following years he can finally learn his desired craft. With diligence and dedication, he soon gains the master’s recognition. Its chains in particular are of excellent quality. After he has passed his journeyman examination, he prepares to return home. As a mercenary, Heini accompanies a caravan that wants to cross the Grimsel. Since this is his way too, and the merchants ask for escort, he joins them. The group is promptly attacked by highwaymen outside Interlaken . Thanks to Heini's quick reaction and skill, the attack can be repulsed, but two mercenaries lie dead, while five of the attackers are killed.

After Heini has safely led the caravan to Airolo , he returns to Göschenen, where he is warmly welcomed. He looks for people among the peasants who can help him to realize his bold plan for the path through the Schöllenen. With the money that had been given to him, he first set up a forge in Göschenen. First the plan is being prepared in secret, because there are some in the valley who still consider Heini to be a crazy weirdo and his company to be hopeless.

At a meeting of able men from Uri, Heini explains his plan and how the mule track could bring respect and livelihood to the valley in the future. Ultimately, there would be an opportunity to free the country from the rule of the hated Habsburgs .

In autumn, construction begins on the new road through the Schöllenen Gorge. In winter, the Göschenen blacksmith forges the chains, hooks and bars required. The village communities are actively involved in the expansion of the pass road between Flüelen and the gorge, while everyone is working together on the difficult section between Göschenen and Andermatt. In the spring, the preparatory work is completed and you move to the Schöllenen to begin the most difficult part of the work. Heini, who now comes to the aid of his experiences in the St. Urban monastery, builds the foundation for the bridge, and the carpenters build the vault over which the bridge is to be erected.

After the masonry was completed and the endurance test was to be carried out, something happened that gave the bridge (and its subsequent successor constructions) the name it still bears today: Devil's Bridge . As the blacksmith is preparing to be the first to cross the bridge, a shepherd escapes a billy goat who is the first to cross the bridge. Then the angry Gret railed: “There you see it, he has allied himself with the devil and has to dedicate his soul to him. Now he has even outsmarted Satan and handed him the soul of the billy goat who was the first to cross this devil's bridge. ”So to this day the legend continues that the bridge was built with the help of the devil.

Construction begins next on the hardest part of the trail. A wooden walkway is to be built around the Kilchbergwand, which is strong enough to support entire fringe communities. The workers use chisels to drive holes in the rock to attach the required hooks. Lead poured into the drill holes firmly anchors the hooks in the wall. Chains were attached to the hooks, two hooks on top of each other, so that crossbars could be placed through the overhanging rock in the lower ends of the chains. The individual yokes are covered with boards, creating a continuous path around the rock.

Finally the plant will be finished and officially opened. In addition to the advantages that the new route will bring for traffic, Uri has now also moved much closer together. Soon the development of the pass traffic takes the expected course and the people of Uri earned their good money on the new road.

But good news also attracts envious people, in this case in the person of Count Rudolf von Habsburg . He arbitrarily increases the customs duty in Flüelen, which again leads the merchants to prefer the Septimerpass to the Gotthard. Otherwise he knows how to stir up conflicts and constantly invent new harassment for the inhabitants of his country. When a friend of Heini's is put in the dungeon because he is caught listening to a song of mockery of the Habsburgs, Heini can no longer keep himself in check and seeks revenge. However, he is drawn into a dispute with the Vogt's servants and has to flee to Airolo.

Three weeks later, the blacksmith was sent word that the intention was to storm the castle of Amsteg, where Heini's friend is being held, and to chase the bailiff away. He immediately returns to the valley, where a council of war is already being held. Fortunately, the people of Uri are aware of the castle's emergency exit, which enables them to conquer the entire castle without bloodshed and to take the Vogt and his family prisoner. From now on, these serve as hostages in negotiations with other bailiffs in the valley. The castle is burned down.

Then Heini, accompanied by his freed friend, goes to see King Friedrich at the royal court in Messina to describe the situation in Uri and to demand freedom from the empire. He reminds the king of his words, which he had spoken nineteen years earlier in Basel, in the presence of Heini, namely that he would give rich gifts to those who could conquer the Schöllenen. The king apologizes that his wish at the time to be ransomed has been forgotten and gives the country of Uri imperial freedom. He returns home, accompanied by two of the king's officials, who are supposed to be faithful to the crimes of the governors.

In the spring of 1231, Heini traveled from Uri to Haguenau, accompanied by other leading men, where the freedom of the empire was to be finally sealed by Henry VII . Heinrich, the son of Friedrich, takes the Urnerland to the property of the empire and in return releases the Habsburgs from their debts. The document was sealed on May 26, 1231 - it has remained in the Altdorf State Archives to this day.

Nothing is known about the further fate of the blacksmith von Göschenen. The book ends with a few patriotic lines: “But we [...] never want to forget that the enthusiasm for work and selflessness of a good, capable man [...] provided the first, important cornerstone for the foundation of the Swiss Confederation for the whole people . The construction of the bridge through the Schöllenen can rightly be seen as the beginning of Swiss freedom […] One for all and all for one! - that was the patriotic belief of the Schmied von Göschenen. In this principle still lies the condition for the prosperity of our people, yes of all peoples, of the great League of Nations. "

Historical background

As can already be seen from the description of the action, the story is based very accurately on historically proven facts. Historically not verifiable were supplemented with legends or frequent doctrines and supplemented with fictional events to a whole. The exact date of the opening of the Gotthard pass road is not known, the first reports of a crossing date from around 1236. Albert von Stade , who is credited with this first mention, suspects the Walsers , who knew how to build long water pipes, behind the construction and at times also the Urserental above the Schöllenen.

The charter of May 26, 1231, in which Heinrich guarantees the land of Uri permanent imperial freedom, suggests that there was already a connection with the street at that time. Hardly any other reason would explain why the German King Heinrich had raised the money to take over the land of Uri from the possession of the Habsburgs and put it directly under the protection of the crown. It is unclear from when the road was really the main traffic axis over the Alps, but at the latest after 1291. For the Uri, the road became economically extremely important, but, as already mentioned in the plot, also brought its downsides, namely that the land in the International politics became the focus. The corresponding conflicts culminate in the legends of Wilhelm Tell and the Rütli oath as well as the real battles of Morgarten and Sempach .

In his short biography of Robert Schedler in 1978, Hans Kaufmann suspected that Schedler used the writings of Aloys Schulte , who put the freedom struggle that Schiller had previously described in his Wilhelm Tell into a different context. Instead of the “purely idealistic striving for freedom of the democratic Alpine cooperatives”, Schulte concentrates on economic and geographical causes for the struggle for freedom. Accordingly, the reason for issuing the license from 1231 is also economically justified. Schedler takes the liberty in his book, from Albert von Stade's assumption that it must have been a blacksmith von Urseren and the freedom considerations for the lower Reuss valley by Aloys Schulte, to create a link and creates the blacksmith von Göschenen. However, neither his origin nor his profession has been conclusively clarified, because more recent research suggests that it was not the Twärren Bridge but the Devil's Bridge that made up the most difficult part of the work. However, since Schedler also ascribes knowledge of bricklaying to the blacksmith, the connection is also well illustrated.

Sources and literature

- Robert Schedler : The blacksmith von Göschenen . Sauerländer, Aarau 1971. Alverna , Wil 2016.

- Dr. W. Oechsli: The beginnings of the Swiss Confederation . For the sixth secular celebration of the Eternal Covenant on August 1, 1291. Ulrich & Co in the reporting house, Zurich 1891 ( full text ).

- Hans Kaufmann: Robert Schedler, in: Grenchner Jahrbuch 1978 . Culture Commission of the City of Grenchen (Ed.), Grenchen 1978, p. 44-46 .

- Pirmin Meier : Sankt Gotthard and the blacksmith von Göschenen . With illustrations by Laura Jurt. SJW Schweizerisches Jugendschriftenwerk, Zurich 2011, ISBN 978-3-7269-0597-2 . (Revision)

Web links

- Radio play version of Swiss Radio DRS from 2008 (standard German and dialect)