Design history

The history of design denotes the history of product design and begins with the mass production of consumer goods in industrial society in the mid-19th century. It also covers the history of graphics and other areas of design.

The first designers

Pre-industrial history has no designer. Only with the development of mass production did the need to manufacture a prototype arise . This new task was mostly taken on by artists. They had the necessary spatial imagination and also had a feel for the taste of the now anonymous customers. In England, the cradle of industry, the new profession was called "modeller". One of the early exponents of the profession was John Flaxman , a well-known London sculptor who worked for the Wedgwood tableware factory. Flaxman's origins from the noble south and his place of work in the smoky north of England already symbolize the dichotomy of the new profession.

Around 1840, around 500 such aesthetic workers were working in Manchester, the center of the textile industry. In the furniture sector around the same time, the German Michael Thonet became a pioneer of industrial design. The designer, emerging from the division of labor, is a creative who has to submit to the factory system. The branches of applied arts, arts and crafts, arts and crafts, and the arts industry emerged from the intermediary position between the opposing worlds of art and industry. The contradictions contained therein persist, but are less conscious today due to the apparently uniform concept of design.

The professional profile of the designer ranges from the anonymous employee of a production company to independent, eccentric personalities like Philippe Starck or Luigi Colani , who behave and are celebrated like pop stars. The unclear job description is still evident today in the large number of "lateral entrants".

The early designers included not only painters and sculptors, but also craftsmen (such as Thonet), later architects, interior designers and engineers, as well as advertising professionals, directors and set designers. This open, interdisciplinary character has long been a characteristic of the new discipline. When the famous design department of the German electrical company Braun was established around the middle of the 20th century, the team was initially composed of representatives of the above-mentioned professional groups. The outstanding importance of the project consisted of a. in the fact that the company management guaranteed the independence of the industrial designers for the first time - not least towards their own technicians. The role of intermediary is also reflected in the central importance of the relationship between entrepreneur and designer. Perhaps this is one of the secrets of Italian design, to which a fixed canon is rather alien, which has always been able to come up with well-harmonizing entrepreneur-designer duos.

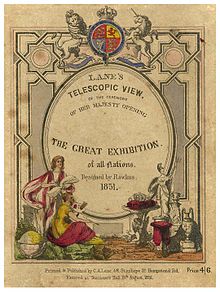

Reform of the Romantics

What the implantation of the fine arts produced in the factory hall usually did not stand up to critical scrutiny. In Great Britain, where industrialization was at its furthest, criticism was also most likely to be loud. Around the middle of the 19th century, the Journal of Design appeared in London , the first magazine to include the term in its title and fill it with ideas for reform. Henry Cole , its active editor, polemicized against the "aberrations of taste of modern designers". The machine age had increased the quantity of goods immensely, but had not produced a style of its own. One indulged in looting historical models. City and apartment became a theater backdrop . At that time Cole developed the didactic idea of an international show for products from different countries. The plan became the Great Exhibition in 1851 . So the first world exhibition was a design project. This in turn led to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the archetype of all arts and crafts and design museums.

At that time England was experiencing an economic recession that shattered belief in the new economic system. The design of industrial goods suddenly appeared to be an important factor for the well-being of the country. The first experiment of design reform from above was not particularly successful. The architect Gottfried Semper , who emigrated from Germany and who, like others, considered the majority of the exhibits at the Great Exhibition to be unsuccessful, summarized his impressions in a “practical aesthetic” in which he proclaimed a “new art” that accepted mechanization and “ pure forms ”. This program, which was first implemented in the first half of the next century, is considered to be the beginning of modern industrial design .

In the second half of the 19th century, a group of artists formed around William Morris in England . This made capitalism responsible for the ugliness of its time and wanted to return to the pre-industrial way of life and work. The Middle Ages were his ideal. The supporters of this alternative movement, soon after one of their exhibitions called Arts and Crafts , founded guilds and artist colonies. Morris managed to trigger a romantic rebellion with his criticism of alienation and - similar to Karl Marx - to spread his anti-capitalist vision internationally. The Studio , the group's magazine, soon became required reading for artists tired of civilization.

Arts and Crafts - in other words handicrafts - inspired the search for the "real and honest". In England there was then a much-noticed rehabilitation of the craft. In the climate of searching, conventions melted. The design reform and the avant-garde art that was emerging at the same time overlapped. These were the best prerequisites for the type of innovative form-inventor, artist personalities such as Peter Behrens , Josef Hoffmann , Charles Rennie Mackintosh , Henry van de Velde or Frank Lloyd Wright . They created “total works of art”, an ideal that prevailed in Art Nouveau and which one z. B. aspired to the project on the Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt.

Emergence of modern design

In Germany, the subculture which originated life reform , with such diverse phenomena of modernity were connected as expressive dance , migratory birds , organic food , nudism and, indeed, modern design. Not least based on the English model, “workshops” had formed around 1900 in various artistic centers that sought to reform living with new, simply designed furnishings. Probably the most successful practice of this was what later became the Deutsche Werkstätten in Dresden (this was also where the artist group “ Die Brücke ” was based), whose most employed designer was Richard Riemerschmid . His simple “machine furniture” not only represented the early attempt to reconcile artistic design and industrial production, it also sold extremely well. "New living" made in Germany received some attention at exhibitions in various countries. So furniture design played a key role from the very beginning of modern industrial design . In connection with the workshop movement, the establishment of further institutions, e.g. B. 1926 the Cologne factory schools run by Riemerschmid can be seen. The most important was the German Werkbund , a national organization for good design that was exemplary internationally. A key figure was founding member Peter Behrens. He was finally able to put his convictions into practice as an “artistic adviser” to the electrical company AEG by completely redesigning its products and appearance. This is considered the first example of a modern corporate identity .

The functionalism of classical modernism

The Bauhaus , too , whose founding manifesto clearly reveals the spirit of Art and Crafts , is inconceivable without the workshop movement, but also not without the collapse of Wilhelmine society and the revolutionary pathos of the post-war period. Probably the most famous design school, whose workforce all came from the artistic milieu, has achieved universal importance not least because of its internationality. The first director Walter Gropius had the ability to inspire talents for the project, including the Hungarians Marcel Breuer and Lázló Moholy-Nagy , the Russian Wassily Kandinsky and the Austrian Herbert Bayer . A decisive impetus came from Holland. There, the artist group De Stijl dealt with the transfer of constructivist ideas to architecture. When her head theorist Theo van Doesburg gave guest lectures on “radical design” at the Weimar Bauhaus, the spark ignited. One spoke now of "industrial design". The Bauhaus became a laboratory for design experiments and the first university for modern design, although this term was not used itself. The professors called themselves " form masters ".

Furniture and home design were once again the focus of interest. Marcel Breuer was inspired by the designs of his Dutch colleague Gerrit Rietveld to do very similar room assemblies before he introduced the machine idiom into the living room with tubular steel furniture and thus triggered an avalanche. The affirmation of industrial production, as also propagated by the Werkbund, and the restriction to the simplest basic forms (as had already been demanded by Gottfried Semper) prevailed. The Bauhaus was by no means an isolated phenomenon. The New Objectivity , still a matter for the avant-garde in the middle of the decade, was the leading style of the time in Germany as early as 1930. The Weißenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart stands for the rapid spread of the movement that is called “classical modernism” today and which is largely defined politically. Many of their representatives saw themselves as socialists.

Much less artistic and formalistic than the Bauhaus was the New Frankfurt project , which, for example, revolutionized the built-in kitchen with the Frankfurt kitchen . The structural implementations were far more social than the Weißenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart.

In France, the Art Deco style also existed alongside functionalism .

When the National Socialists came to power in Germany, they banned the Bauhaus and imposed professional bans on Jews and avant-gardists, many of whom emigrated, and others. a. to the USA, where they were able to teach at Black Mountain College . From here, there was a great impact on American contemporary art and the arts and crafts. However, some modernists, including Bauhaus students, were able to continue working. Similar to Italy, the regime wavered in its aesthetic line between conservatism and modernism.

Industrial design in the USA

The type of the modern designer emerged twice on different sides of the Atlantic, under opposite signs. While classical modernism was programmatically oriented, a commercial variant developed around the same time in the USA: industrial design . American capitalism had become the first consumer society in the early 20th century. In addition to new sales methods such as mail order and supermarkets, there were a number of innovative products. Their attractive design came into focus when symptoms of overproduction began to appear in the mid-1920s. The auto industry became a pioneer. In 1926, the General Motors concern set up a department for "Art and Color", which increased sales through regular model cosmetics, later called styling. Companies in other industries adopted the method. This was the first job market for industrial designers.

The men of the first hour included Henry Dreyfuss , Norman Bel Geddes , Raymond Loewy , Walter Dorwin Teague and Russel Wright . Their professional backgrounds were surprisingly consistent. Teague and Geddes came from advertising, as did Loewy, who had also worked as a decorator at times. Dreyfuss, Geddes and Wright, who knew each other personally, had made careers as set designers on Broadway . America's early designers, who eventually joined forces in the Industrial Designers Society of America (the first professional association of their guild), were "commercial artists," accomplished artisans of visual suggestion . Streamlining became her preferred style . In the recession of the 1930s, it was considered the miracle cure. When Loewy created a “streamline” refrigerator for the Sears department store chain , carefully improved the operating functions of the interior and then doubled sales figures in one year, it became a national event. Loewy's re-copied refrigerator became an icon of the Western lifestyle. In early American industrial design, an unconditional, strictly commercially oriented pragmatism was combined with a highly developed talent for theatrics. This created not only almost the entire inventory of consumer society, but also a considerable store of myths . It manifested itself in 1939 at the New York World's Fair, which was largely shaped by the designers mentioned, but on which z. For example, the Scandinavians with their “organic” design language also received great attention for the first time.

Since the early 1930s, the New York Museum of Modern Art has acted as the mouthpiece of classical, strongly German-influenced modernism, for which the name International Style , derived from an exhibition title , was used. This gained in importance when, towards the end of the 1930s, almost the entire Bauhaus elite emigrated to the USA and, as professors, spread the radical theory of form.

Word history

In 1950, after a trip to America during which he met the design elite of the leading industrial nation, the Swede Sigvard Bernadotte founded an office for industrial design in Copenhagen, probably the first company outside the USA to bear this name and also to adapt the agency model. Two years later, Raymond Loewy, who was born in France, opened a branch in Paris. The Americanism he did not expect his countrymen at the time. He called the company Compagnie de l'Estétique Industrielle .

The term design has now also been re-imported to where it actually came from, namely Great Britain. In English, the word, which is borrowed from the synonymous French dessin and originally derived from the Latin designare or Italian disegno , fans out into a number of related meanings, such as design, drawing, scheme and pattern, but is also used for construction in technical terms Sense used as well as for its opposite, the decoration. Either the design can be meant as a process or the product that emerges from it. This is often not sharply separated. As if that weren't enough cause for misunderstanding, a few more meanings were added to the shimmering abstraction in its history. For a long time it was only known to experts outside of the English-speaking world and only became common parlance in the western world in the 1980s.

The late functionalism, the good form

The idea of using the museum as an institute for the formation of taste originates from the 19th century and was taken up by the occupying powers in the post-war period as an educational method "for the Germans corrupted by the dictatorship". The most important design institution after the Second World War, the Ulm School of Design , was an attempt at cultural re-education and only worked with the million that the American High Commissioner made available. Max Bill, its architect and first director, had managed to set up an exhibition on the subject of “ good form ” in 1949 . At a time when German cities were still in ruins and thoughts revolved around whether or not you would have something to eat the next day, an astonishing idealism. This was shared by numerous German intellectuals who longed for a new beginning and who, like the physicist Werner Heisenberg and the writer Carl Zuckmayer , supported the project. The new university saw itself explicitly as a Bauhaus reincarnation. As with the famous role model - and previously with the Deutsche Werkstätten - the assumption was that the designed environment was an integral part of the curriculum. The university building with its large windows and sparse concrete walls - the architect was Max Bill - exuded exactly that purism that was later evident in the products. Through the cooperation with the electrical company Braun , whose appearance and products were redesigned in the mid-1950s, the Ulm principles could be put into practice for the first time. The graphic designer Otl Aicher and the product designer Hans Gugelot were key players. But there were also other role models, such as the Italian office machine manufacturer Olivetti , whose advertising department was just as innovative as the products mostly designed by the architect Marcello Nizzoli .

The economically powerful United States, above all the couple Ray and Charles Eames, set the style . But the losers of the war, Germany and Italy, and not least Scandinavia, also provided strong impetus. From 1954, the “Design in Scandinavia” exhibition had toured all over North America for several years. Perhaps the most successful design campaign of all time, it led to a series of other exhibitions on the same topic. No important country was left out. Until then, neither Arne Jacobsen nor Bruno Mathsson would have thought of calling themselves a designer. Suddenly in international demand, Scandinavians saw themselves at home as architects, artists, artisans or designers. With the creation of the word "Scandinavian design" they were declared designers. The older names gradually began to disappear. Scandinavian handicrafts, which it was essentially about, embodied qualities that came close to what was now understood in America as “good design” - the counterpart to “good form”. Since the Museum of Modern Art organized a series of exhibitions under this title, the notion of the ultimate, "classical" style in the form of functionalism of Nordic provenance penetrated into the parlors of the middle class for the first time. The new policy of enlightenment was also supported by the Design Councils, which were based on the American model in almost all Western countries. Above all, those countries that had discovered the export of beautiful, expensive goods to the USA as a way of restoring their trade balance, made use of the new terminology. So it came about that in Denmark people only spoke of “Danish Design” and “Bel Design” was used in Italy. Design as common Americanism as we know it today was a marketing term introduced in the 1950s that entered into a semantic affair with the functionalist world improvement mentality. The Design Council of the USA has brought it back in a slogan on the point at issue: Good Design and Good Business .

Postmodern

When the Memphis group first demonstrated their weird objects in 1981, the initially perplexed public soon reacted as if they had been waiting for this cheek a long time. There were quite a few critics who could hardly cope with the disrespect. But ultimately there was a general consensus: Memphis swept away the last taboos in design history like a cleansing thunderstorm - similar to punk in pop music. The resolution that design is there for eternity has been shelved (and in the best case stored in the ecological "sustainability" niche).

Instead, superficiality and unrestrained eclecticism prevailed. Even if this was ultimately only about the "Great Design Swindle", it was a turning point that had long been indicated: in plasticine pop design of the 1960s, in works such as those of Gaetano Pesce , an art deserter who The pleasure principle set in again, but above all in the “Radical Design” protest movement that was inflamed in the Italian underground and which reviled functionalism as an ideology. At a time when anti-capitalism was a good moral tone among creative people, design could not go unscathed either. The result was a romantic déjà vu experience: although handicrafts were also condemned as superfluous bourgeois luxury, on the other hand self-realization was at the top of the list of values of the young skeptics. Quite a few therefore found in handicrafts - like one William Morris - the key to a better world.

But neither capitalism nor design was finished. On the contrary: the scruffy, anti-authoritarian 1960s only opened the floodgates. Nonconformism and pop culture created the basis for something really new: lifestyle consumption. In the course of an unprecedented hedonism , design brands advanced to status symbols , designers to pop stars and their job the dream job of the MTV generation . Design finally entered the world vocabulary. Italy's strengths that made it the leading design nation were, not least, entrepreneurs who deserved this name and who reinforced the author's design with foreign creative staff (the Memphis mentor and Artemide boss Ernesto Gismondi is just one example). Where not only everything is allowed and we have long since got used to zapping through the styles with relish, industry and avant-garde can also merge easily.

One country where this is on the government agenda is Great Britain. During the low eighties, the “creative industry” was declared the new engine for the gross national product. From mega agencies with hundreds of tie-and-collar designers to style surfers like Neville Brody who pick up their material from the street, from Jasper Morrison , the guru of the new simplicity, to Ron Arad, probably one of the most prominent “designer-makers” . This is the name given to those lone fighters who, mostly with artistic subtlety, recycle set pieces from civilization and are actually known for their recalcitrant attitude towards the industry that they then gave a boost to innovation.

The British established London - alongside Milan - as a design metropolis and the annual 100% Design trade fair a successful project. Neo-Scandinavianism followed, and finally France, where the generation after Starck succeeded internationally. In Karim Rashid, New York, where a design mile had emerged at the end of the 1990s, got a new design prince in the tradition of Raymond Loewy. It is certainly no coincidence that both are emigrants. The international networking that had always determined design became even closer in the age of the jet and the Internet. This is also reflected in the worldwide distribution of the author's design , which the metal goods manufacturer Alessi once introduced. The international design elite are committed to the system of opera choirs. At the same time, design has also penetrated mass consumption.

The extensive digitalization of the design process from the model to the production tool accelerated the style carousel. Whether in the car, electronics or furniture industry, a series of models in an unprecedented variety and frequency is now challenging consumers. This also made the wave of re-editions possible. What the forefather of all postmodernists, Josef Frank, already knew during the Bauhaus era seems to be true: “Whichever style we use is irrelevant. What modernity has given us is freedom. "

See also

literature

- Peter Benje: Woodworking by machine. Its introduction and the effects on forms of business, products and production in the carpentry trade during the 19th century in Germany. Darmstadt 2002. Online: https://tuprints.ulb.tu-darmstadt.de/143/

- Kathryn B. Hiesinger and George H. Marcus: Landmarks of Twentieth-Century Design . Abbeville Press, New York 1993. 431 pp. ISBN 1-55859-279-2

- Bernd Polster: Can you also sit on it? How design works . Dumont Buchverlag, Cologne 2011. 248 pp., ISBN 978-3-8321-9365-2

- John A. Walker: History of Design - Perspectives of a Scientific Discipline . scaneg Verlag, Munich 2005. 242 pages, ISBN 3-89235-202-X

- Gert Selle: History of Design in Germany . Frankfurt / Main u. New York, Campus Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3-593-35154-4

- Bernhard E. Bürdek: Design: history, theory and practice of product design . Cologne, DuMont Buchverlag, 1991, ISBN 3-7701-2728-5