Diolkos

The Diolkos ( Greek Δίολκος , from dia διά 'through' and holkos ὁλκός 'train') was an ancient Greek barrow route across the Isthmus of Corinth , on which ships were transported between the Corinthian and Saronic Gulf . The shortcut across the isthmus made it possible to avoid the dangerous circumnavigation of the Peloponnese .

The main task of the Ziehweg was the transfer of goods, while in times of war it was also preferably used to accelerate military operations. The 6 to 8.5 km long paved Rillenweg functioned on the railway principle and was from approx. 600 BC. In operation until the middle of the 1st century AD. On this scale, it represented a combination of ruts and overland transport of sea vehicles, which was unique in antiquity .

Modern exploration and exposure

The modern scientific discussion of Diolkos revolves around three main questions:

- the interpretation of the ancient sources, especially with regard to the age and the reasons for the opening of the Ziehweg;

- the archaeological research of the remains on the isthmus and the determination of the route;

- the evaluation of its military and economic function in antiquity.

Technical considerations for the feasibility of the overland transport of the ships were also repeatedly the focus of interest, whereby theoretical calculations were also attempted to calculate the physical forces to be overcome.

The chief engineer of the Corinth Canal, Béla Gerster , carried out a detailed investigation of the topography of the isthmus before the breakthrough , but did not find the Diolkos . Remains of the ship cart path were probably first identified by the German archaeologist Habbo Gerhard Lolling in the Baedeker edition of 1883. In 1913, JG Frazer reported in his commentary on Pausanias about traces of an ancient stone path across the isthmus, while parts of the western quay were discovered in 1932 by Harold North Fowler .

Systematic excavations were finally carried out from 1956 to 1962 by the Greek archaeologist Nikolaos Verdelis , who uncovered a more or less continuous piece of 800 m in length and located a total of 1,100 m. Verdelis' excavation report still serves as the basis for modern interpretations, but the full publication of his research results was prevented by his premature death, so that many questions about the exact nature of Diolkos remained . Additional on-site research in addition to Verdelis' work was later published by Georges Raepsaet and Walter Werner.

Nowadays, especially in the western section, significant parts of the Diolkos are endangered by erosion, which originates from ship operations in the nearby canal. Critics accusing the Greek Ministry of Culture of continued inaction have filed a petition for the preservation and restoration of the registered archaeological site.

Traffic situation

The Diolkos allowed ships on the voyage from the Ionian Sea to the Aegean Sea to avoid the dangerous circumnavigation of the Peloponnese with its headlands protruding far into the sea. Cape Malea in particular was feared for strong storms, whereas the Gulf of Corinth and the Saronic Gulf were relatively calm waters. In addition, by using the overland route, the shipping route, in particular to and from Athens, could be shortened considerably.

history

The ancient sources are silent about the age of Diolkos . For Thucydides (460–395 BC) the Diolkos already seemed to be something old. The archaeological evidence indicates a building at the end of the 7th or beginning of the 6th century BC. When Periander was the tyrant of Corinth . On some stone blocks there are letters of the Corinthian alphabet from the beginning of the 6th century BC. The Diolkos reportedly continued to operate regularly until the middle of the 1st century; thereafter the written records break off. It may have been made permanently unusable by Nero's failed canal project in AD 67. This is supported by the fact that the ancient excavation work, which has been proven to be 40–50 m wide and up to 30 m deep, ran along exactly the same route as the later Corinth Canal , which now cuts through the ancient paved road. Much later, warship transports in 868 and around 1150 were probably no longer handled via the Diolkos due to the long period of time in which no information about the use of the barrow path has been received .

Role in war

The Diolkos played an important role in ancient naval warfare . Greek historians report several naval operations between the 5th and 1st centuries BC. When warships were pulled across the Diolkos to save time. During the Peloponnesian War , the Spartans planned to drag warships to threaten Athens to the Saronic Gulf (428 BC), while later they carried over a squadron that hurriedly sailed on for operations in Chios (411 BC). 220 BC BC Demetrios of Pharos had his fleet of about 50 ships pulled across the isthmus to the Bay of Corinth. Three years later, 38 Macedonian warships were sent across by Philip V while the larger ships of his fleet were sailing around Cape Malea. An inscription now in the Archaeological Museum of Corinth reports that in 102 BC. BC Marcus Antonius Orator let the Roman fleet pull across the isthmus. After his victory at Actium (31 BC), Octavian advanced as quickly as possible against Mark Antony by having some of his 260 Liburnians dragged across the isthmus. In 868 AD, the Byzantine general Niketas Oryphas under Emperor Basil I had his entire fleet of 100 dromons dragged across the isthmus in a swift operation, but probably took a different route due to the probably dilapidated state of Diolkos .

Role in trade

Despite the frequent mention of Diolkos in connection with military operations, modern research suggests that the main purpose of the barrow barrow was for the transfer of goods, given that warships did not need to be transported very frequently, and because ancient historiography was increasingly advocating War than interested in trade. Remarks by Pliny the Elder and Strabo , who described the Diolkos as regularly operating in peacetime , also indicate a commercial function. Since the construction of the Diolkos coincides with the development of the Greek monumental architecture , the overland route could initially have served especially for the west-east transport of heavy goods such as marble , monoliths and timber . Although the amount of tariffs Corinth was able to levy on the Diolkos lying on its territory is not known, the fact that the route was used and maintained long after it was built suggests that it was a long time for ancient merchant ships an attractive alternative to driving around Cape Malea. For Corinth, too, Diolkos was a worthwhile project. In addition to land trade, it was now able to control sea trade via the isthmus. In the 6th and 5th centuries BC At the western end of the Diolkos near today's Poseidonia an important settlement.

Building structure

Course and transport

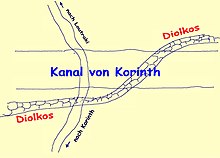

The Diolkos runs over the narrowest part of the isthmus, where it follows the terrain in a winding course to avoid steep inclines. The road crosses the isthmus with an average gradient of 1:70 at a height of approx. 79 m, with the steepest section having a gradient of up to 6%. The total length of the Diolkos is estimated at 6-7 km, 8 km or 8.5 km, depending on the number of bends in the road. A total of 1.1 km of it has been archaeologically documented, mainly at the western end. There the well-known section begins at a pier south of the canal, runs parallel to the waterway for a few hundred meters and then changes to the north side, where it continues in a slight curve along the canal for about the same length. In its further course, the Diolkos either followed the course of the modern canal in a straight line or swung in a wide arc to the south. The cart path ends on the Saronic Gulf at the village of Schoinous near today's Kalamaki , which Strabo described as the eastern end point. Some sections of the Diolkos were destroyed by the 19th century canal or other modern structures.

The Diolkos was a paved path made of hard limestone with parallel grooves about 160 cm apart. The path was between 3.4 and 6 m wide. Walls ran to the left and right of the Diolkos to prevent derailment. There were also trenches on both sides from which guards could monitor the transport. Since there is little inferred from ancient sources about how the ships were transported over, the manner in which the ship was transported must largely be reconstructed from the archaeological findings. The grooves indicate that the transport on the Diolkos was carried out with a type of wheeled vehicle, which was called Olkos in ancient times. Either the ship and the cargo were pulled across on different carts, or the cargo was just brought over to be loaded onto another ship on the other side. It is believed that these were usually larger boats than ships, although technical analysis showed that transporting triremes (25 t, 35 m long, 5 m wide) was technically feasible but difficult. In order to prevent the risk of the keel breaking in the middle during transport, thick ropes, so-called hypozomata , must have been used, which were stretched from bow to stern to stabilize the hull . The ship and cargo were probably pulled by humans and animals with the help of ropes , pulleys and possibly anchor winches . At the western end a ramp of 10 × 8 m was found, the western end of which was below the water level. The ships were pulled out of the water via this ramp with the help of wooden beams and loaded onto the wheeled vehicles. From the 4th century BC A wooden lifting system seems to have been used to lift and load the ships.

The scientist Tolley attempts to determine the number of crews that were required at that time to transport a trireme over the ridge of the isthmus. Assuming that a trireme soaked with water, including a mobile pedestal, weighs 38 t and a person can pull 300 N over a longer period of time , depending on the incline to be overcome and the condition of the groove path, a pulling force of 112 to 142 men were needed (33,550 to 42,500 N). When starting it would have been almost 180 people. At a speed of 2 km / h and an estimated route length of 6 km, the transfer over the isthmus would have been accomplished in three hours. Raepsaet, on the other hand, uses lower transport loads and friction values to calculate a max. Pulling force of 27,000 N, which would have required significantly smaller work groups. The use of carts of oxen, which Tolley rejects in his computer model with reference to their relatively decreasing work performance, would have made sense under these conditions. In both calculations, the human effort on the pull path must be classified as considerable in any case.

Antique railroad

According to the British art historian MJT Lewis, the Diolkos a " railroad " ( eng. Railway ) in the sense of a prepared path represents the so driving a vehicle on it, that it can not leave the track. Between 6 and 8.5 km long, regularly in operation for at least 650 years, and open to all for a fee, the Diolkos was even a public railway, an idea that only reappeared in the 19th century. The Diolkos was also similar to modern railways in its track width of 160 cm .

On the other hand, a detailed archaeological examination of the Rillenweg seems to convey a differentiated picture. The appearance of the ruts in the course of the two main sections varies between a “V” profile and a rectangular cross-section. While there is agreement that the rectangular ruts in the eastern part were deliberately carved into the paving stones to steer cart wheels, the V-shaped ones in the western area are interpreted by some authors as the result of wear or are not visible at all. However, here too, the clear curvature of the paved path suggests that grooves were intentionally created. In addition to the two parallel main grooves, there are also significantly flatter grooves in this section on the sides of the road. These are interpreted as signs of wear on the rear wheels of the transport base, which, when entering a curve, describe a smaller radius, deviating from the lane, due to their rigid rear axle. In general, the different groove shapes in the western and eastern part, by the long service life of the Diolkos be explained, in the course must have been its appearance significantly changed by repairs and other structural changes.

The so-called ramp, which is located on an incline between the two sections of the route, creates difficulties for interpretation. These are two parallel rows of stone blocks running at a distance of about 60 cm in the middle of the roadway, with a length of about 15 m, but originally probably twice as long, which Raepsaet and Werner considered as guide stones for the transport become. The further interpretation of the construction by Raepsaet as a reloading point for two different types of wheeled vehicles is rejected by Lewis as impractical, since it would have required a new loading of the ship or freight 600 m behind the ship's landing stage.

Functionally, the Diolkos shipbarrow path can be viewed as a combination of two techniques that were quite widespread in antiquity, namely track steering based on the railroad principle and land transport by ship. Ancient authors know about the latter mainly in connection with military operations. Herodotus already considered the construction of the Athos Canal superfluous, since the Persian King Xerxes I "could have pulled his invasion fleet across the isthmus without any effort". In Sicily , the tyrant Dionysius I once had an 80 trireme strong squadron transported 20 stadiums (approx. 3.5 km) over land, while Alexander the Great even transferred his ships from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates during his Asian campaign - albeit in a dismantled state. The best-known example is probably Hannibal's evasive maneuver , who died in 212 BC. BC let his fleet, blocked by the Romans in the Tarentine port, drag through the streets of the city to the open sea. Measures considered to be secure in such overland transports included the use of hoisting machines to lift the ships out of the water, the preparation of the pull-way beforehand and the use of cattle next to people as pulling forces.

In contrast, the principle of ruts was used on a smaller scale in the civil sector. For example, in the theaters of Megalopolis (3rd century BC), Sparta (approx. 30 BC) and Eretria, short, maximum 34 m long double grooves across the stage were discovered, which either served to shift the set or carried a mobile platform on which the actors were pulled into the hall by invisible hands because of the theatrical effect. On the Roman road over the Kleiner Sankt Bernhard , short ruts carved out of the rock can also be made out, which - comparable to the function of a modern guardrail - should prevent the carts from leaving the pass path. The principle has also been used in ancient mining: A 150 m long tunnel in the Roman gold mine in Três Minas in Portugal (1st century AD) has a grooved route with a track width of 1.20 m and periodic tunnel widening presumably to let oncoming traffic through. In the scale in which the connection between the two elements was implemented in the construction and operation of the Diolkos , the ship cart path was probably unique in antiquity.

Historical sources

The following ancient and medieval sources mention ship transports across the isthmus. Since the Diolkos is rarely mentioned directly by name, an analysis of related expressions and paraphrases is important for understanding the transfer activities. In chronological order:

- Thucydides 3.15.1, 8.7, 8.8.3-4

- Aristophanes , Thesmophoriazusai , 647-648

- Polybios 4.19.7-9 [318], 5.101.4 [484], frag. 162 (ed. M. Buettner-Wolst)

- Titus Livius 42.16.6

- Strabo 8.2.1 [C.335], 8.6.22 [C.380], 8.6.4 [C.369]

- Pliny , Naturalis historia , 4.9-11, 18.18

- Cassius Dio 51.5

- Hesychios (ed. Schmidt, I, p. 516.80)

- Suda , keyword Diisthmonisai ( Διισθμονίσαι ), Adler number: delta 1048 , Suda-Online

- Georgios Sphrantzes 1.33

- Al-Idrisi (ed.PA Joubert: Géographie d'Idrisi 2, Paris 1840, p. 123)

More barrow routes

Apart from Diolkos near Corinth, there are sparse written references to two other barrow routes in Roman Egypt , both of which also operated under the name "Diolkos". The doctor Oreibasios (c. 325–403 AD) reports two passages from the 1st century AD, in which his colleague Xenocrates of Aphrodisias casually mentioned a Diolkos near the port of Alexandria , who is at the southern tip of the Pharos Island. Ptolemy briefly reports in his book on geography about another Diolkos who connected a sand-covered mouth of the Nile with the Mediterranean Sea . Neither Xenocrates nor Ptolemy provide details on the respective cart paths.

Remarks

- ↑ Although Diolkos is not explicitly mentioned in these historical sources, its use is generally accepted because it existed before and was still available afterwards (Cook 1979: 152, note 7; MacDonald 1986: 191–195 (192, note. 6).

- ↑ For example, according to Tolley, three pairs of oxen only have twice the pulling power of a team. On the Diolkos , the relatively declining workload of the oxen would have been all the more significant since a very large number of teams would have been required for ship transport (Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 261).

- ↑ Strictly speaking, one would have to speak of the tram principle, since the ancient rails were normally grooved below the carriageway level. Raised (wooden) rail tracks were also known, such as in the Heron's mechanical puppet theater (Lewis 2001: 10).

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Lewis 2001: 8-19 (8 & 15)

- ↑ a b c Verdelis 1957: 526-529 (526); Cook 1979: 152-155 (152); Drijvers 1992: 75-76 (75); Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 233-261 (256); Lewis 2001: 11

- ↑ a b c d Lewis 2001: 15

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 235 & 237

- ↑ a b Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 252f., 257-261

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 235

- ↑ a b Werner 1997: 98

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 236

- ↑ Nikolaos Verdelis: Le diolkos de L'Isthme. In: Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique . 1957, 1958, 1960, 1961, 1963

- ↑ a b c d Lewis 2001: 10

- ↑ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 239; Lewis 2001: 10

- ↑ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 233-261; Werner 1997: 98-119

- ↑ Pictures of the decay of Diolkos between 1960 and 2006 . Archived from the original on April 10, 2008. Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved March 22, 2008.

- ↑ Petionsite.com: Save and Restore Ancient Diolkos . Retrieved March 22, 2008.

- ↑ Drijvers 1992: 75; Lewis 2001: 10; Werner 1997: 98

- ↑ Werner 1997: 98–119 (99 & 112)

- ↑ a b c d Kissas 2013: 29

- ↑ Lewis 2001: 11

- ↑ Cook 1979: 152, note 8; Lewis 2001: 11

- ↑ Gerster 1884: 225–232 (229f.)

- ↑ Cook 1979: 152, note 7; Werner 1997: 114

- ↑ a b Cook 1979: 152, note 7; Lewis 2001: 12

- ↑ Thucydides 3.15.1 (English translation)

- ↑ Thucydides 8.7-8 (English translation)

- ↑ Polybios 4.19.77-79 (English translation)

- ↑ Polybios 5.101.4 (English translation)

- ↑ a b Tsakos, Pipera-Marsellou, Tsoukala-Konidari 2003

- ↑ Werner 1997: 113f.

- ↑ Werner 1997: 114

- ^ Cook 1979: 152; MacDonald 1986: 192; Raepsaet 1993: 235; Werner 1997: 112; Lewis 2001: 13

- ^ Cook 1979: 152

- ^ Raepsaet 1993: 256; MacDonald 1986: 193; Lewis 2001: 14

- ^ MacDonald 1986: 195

- ↑ a b c d e Werner 1997: 109

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 246

- ↑ a b 6–7 km estimated by: Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 246; 8 km estimated by: Werner 1997: 109; 8.5 km estimated by: Lewis 2001: 10

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 237-246

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 238 (Fig. 3)

- ↑ Lewis 2001: 10; Werner 1997: 108 (Fig. 16)

- ↑ Werner 1997: 106

- ↑ a b c d Lewis 2001: 12

- ^ Cook 1979: 152; MacDonald 1986: 195; Werner 1997: 111

- ^ Cook 1979: 153; Lewis 2001: 14

- ↑ Drijvers 1992: 76; Lewis 2001: 14

- ↑ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 259-261

- ↑ Werner 1997: 109 (Fig. 17)

- ↑ Werner 1997: 111

- ↑ Werner 1997: 112

- ↑ Lewis 2001: 12f.

- ↑ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 243; Werner 1997: 106; Lewis 2001: 12

- ↑ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 237-243; Werner 1997: 103-105

- ↑ Werner 1997: 106f.

- ↑ Lewis 2001: 13

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 238f .; Werner 1997: 107f.

- ↑ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 254; Lewis 2001: 12

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 249f.

- ↑ Lewis 2001: 9f.

- ↑ Lewis 2001: 9

- ^ Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 233

- ↑ All sources by Raepsaet & Tolley 1993: 233, except for Titus Livius and al-Idrisi (Lewis 2001: 18)

- ↑ Titus Livius 42.16.6 (Latin original)

- ↑ Coll. Med II, 58, 54-55 (CMG VI, 1, 1)

- ^ Fraser 1961: 134 & 137

- ↑ Fraser 1961: 134f.

literature

- RM Cook : Archaic Greek Trade. Three Conjectures 1. The Diolkos. In: Journal of Hellenic Studies . Vol. 99, 1979, pp. 152-155.

- Jan Willem Drijvers: Strabo VIII 2.1 (C335). Porthmeia and the Diolkos. In: Mnemosyne . Vol. 45, 1992, pp. 75-76.

- PM Fraser: The ΔΙΟΛΚΟΣ of Alexandria. In: The Journal of Egyptian Archeology. 47: 134-138 (1961).

- Bela Gerster: L'Isthme de Corinthe: tentatives de percement dans l'antiquité. In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique. Vol. 8, No. 1, 1884, pp. 225-232 (229f.)

- MJT Lewis: Railways in the Greek and Roman world. In: A. Guy, J. Rees, (Eds.): Early Railways. A Selection of Papers from the First International Early Railways Conference . 2001, pp. 8–19 (10–15) ( PDF online )

- Brian R. MacDonald: The Diolkos. In: Journal of Hellenic Studies. Vol. 106, 1986, pp. 191-195.

- Georges Raepsaet, Mike Tolley: Le Diolkos de l'Isthme à Corinthe. Son tracé, son fonctionnement. In: Bulletin de correspondance hellénique . Vol. 117, 1993, pp. 233-261.

- Walter Werner: The Corinth Canal and its predecessors. In: The logbook. Special issue. Hamburg 1993.

- Walter Werner: The Diolkos. The ship tug on the Isthmus of Corinth. In: Nürnberger Blätter to archeology . 10: 103-118 (1995).

- Walter Werner: The largest ship trackway in ancient times: the Diolkos of the Isthmus of Corinth, Greece, and early attempts to build a canal. In: International Journal of Nautical Archeology. Vol. 26, No. 2, 1997, pp. 98-119.

- Konstantinos Kissas (ed.): Antike Korinthia , Athens 2013, p. 29.

- K. Tsakos, E. Pipera-Marsellou, D. Tsoukala-Konidari: The Isthmos of Corinth , Athens 2003, pp. 10-13.

See also

Web links

- Petition for the preservation and restoration of Diolkos

- MJT Lewis: "Railways in the Greek and Roman world" (PDF; 216 kB)

- Rillenweg (photo)

Coordinates: 37 ° 56 ′ 18.1 ″ N , 22 ° 58 ′ 52.2 ″ E