Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers

The Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers ( encyclopedia or a well thought-out dictionary of sciences, arts and crafts ) is a French-language encyclopedia , probably the most famous early encyclopedia as understood today. It was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert and contains contributions from other 142 editors, the so-called encyclopedists . Above all, Louis de Jaucourt should be mentioned here. The first volume appeared in 1751. In 1780 the series was completed with the 36th and last volume.

The Encyclopédie is one of the major works of the Enlightenment . It comprises more than 70,000 articles.

In the follow-up work, the Encyclopédie méthodique , the Encyclopédie was revised, expanded and re-divided into various specialist dictionaries. 166 volumes appeared between 1782 and 1832, edited by the publishers Charles-Joseph Panckoucke and Thérèse-Charlotte Agasse .

Another follow-up work was the Encyclopédie d'Yverdon by Fortunato Bartolomeo de Felice (1723–1789), which appeared as a quarto edition in the period from 1770 to 1780.

Goal setting

The basic idea of the Encyclopédie and its editors was to collect the entire knowledge of the time and make it publicly available to the world. Diderot in the article Encyclopédie :

“Indeed, an encyclopedia aims to collect the knowledge scattered on the surface of the earth, to present the general system of this knowledge to the people with whom we live and to pass it on to the people who will come after us, so that the work of the past centuries is not useless to the centuries to come; so that our grandchildren not only become more educated, but at the same time more virtuous and happier, and so that we do not die without having rendered our service to humanity. "

It is remarkable that Diderot made it his goal not only to collect the knowledge of the educated middle class, but that of all people. The Encyclopédie should not only summarize and make available the knowledge of a small group, but also absorb and present the knowledge of ordinary people. And although Diderot and d'Alembert themselves belonged to the bourgeoisie and probably also the clear majority of the readership came from the bourgeoisie, the editors have endeavored to enrich their compilation with articles by artisans. For example, the article on watchmaking (French: horlogerie ) is said to have been contributed by a simple watchmaker.

However, the intentions of the editors went beyond a mere presentation of the knowledge. Even the title describes Encyclopédie as dictionnaire raisonné , i.e. a critically thought-out dictionary constructed according to reason. Diderot already described the concept in his Prospectus of 1750:

"En réduisant sous la forme de dictionnaire tout ce qui concerne les sciences et les arts, il s'agissait encore de faire sentir les secours mutuels qu'ils se prêtent; d'user de ces secours, pour en rendre les principes plus sûrs […]; d'indiquer les liaisons éloignées ou prochaines des êtres […] de former un tableau général des efforts de l'esprit humain dans tous les genres et dans tous les siècles […] »

“In the lexical summary of everything that belongs in the fields of science, art and craft, the aim must be to make their mutual interdependence visible and to grasp the principles on which they are based more precisely with the help of these cross-connections [...] it is about showing the more distant and closer relationships of things, [...] to paint a general picture of the efforts of the human spirit in all areas and in all centuries [...] "

Diderot wrote to his friend Sophie Volland in 1762: “This work will surely bring about a transformation of the spirits in time, and I hope that the tyrants, the oppressors, the fanatics and the intolerants will not win. We will have served humanity […] ”.

The work is the last significant encyclopedia which is based on a tree of knowledge in the manner of Francis Bacon , but which already deviates from it in significant places; it thus initiates an "epistemological change of direction that transformed the topography of all human knowledge" ( Robert Darnton ).

The editors claimed to measure all human activities against the standard of reason and to make them questionable. They advocated equality , i. H. no one should rule over other people. Hidden but clear, the Encyclopédie criticized the state and the church without Diderot having to expose himself to the accusation of “unbelief”. The booksellers were always able to point out the balance of the work, while the educated public knew how to read between the lines.

Both the methods of Thomas Aquinas and René Descartes are rejected and only the empirical approach of John Locke ("knowledge through experience") and Isaac Newton are seen as authoritative. Francis Bacon's slogan “ Knowledge is Power ” also became more and more a key concept.

construction

The 17 text volumes of the Encyclopédie contain 71,818 articles on around 18,000 pages. The text contains 20,736,912 words, of which 391,893 are different. This set required a well-structured order or system. Since the Encyclopédie aimed to explain all areas of science, a few, always different, areas were covered in each volume, with the articles in alphabetical order.

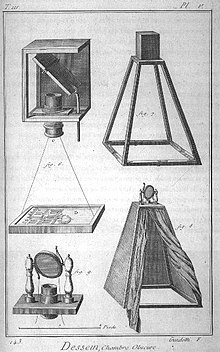

Another focus of the Encyclopédie were images that were drawn very precisely and true to detail. These were, for example, anatomical sections through living beings, monuments , ruins known at the time , works of art , architecture or everyday objects.

The eleven additional picture board -Bände contain about 7,000 pages 2,885 engravings and 2,575 notes.

Publication history

Beginnings

As early as 1695 to 1697, Pierre Bayle's historical-critical lexicon Dictionnaire historique et critique appeared , from which Denis Diderot included the article Skepticism in the Encyclopédie . In 1728, Ephraim Chambers had published the two-volume encyclopedia Cyclopaedia in England with considerable success .

From 1743 the Englishman John Mills and the German Gottfried Sellius pursued a project that aimed to translate the Cyclopaedia into French and expand it into a five-volume work. To do this, they arranged with the French publisher André-François Le Breton , who had to obtain the imperative royal privilege to print such a work. He received this as his personal (inheritable) property in 1745, thus betraying his partners.

When the five folio volumes in the manuscript were almost ready, Mills fell out with his publisher Breton. In order to save the work, he won the Abbé Jean Paul de Gua de Malves, known as a translator and mathematician . The suggested a thorough revision, but then does not seem to have performed any further. Le Breton then turned to Denis Diderot , who started the work.

Le Breton's economic capacity did not do justice to the new giant project and Diderot's knowledge was insufficient to adequately cover the fields of physics and mathematics. So the publisher needed a financier, Diderot a competent partner whom he found in d'Alembert. From 1750 a group of encyclopedists worked under Diderot (139 others are known by name, including Louis de Jaucourt , Melchior Grimm , Jean-François Marmontel , Montesquieu , d'Holbach , Quesnay , Jean-Jacques Rousseau , Turgot and Voltaire ). The venture was delayed again because Diderot had to serve several months' imprisonment for his publication Lettre sur les aveugles in 1749 and was only released at the request of the publishers.

Problems

The authors of the Encyclopédie all took in different ways a critical attitude towards the Catholic Church that dominates in France . Among them there were undogmatic Christians, deists , pantheists , agnostics or authors who were inclined to atheism . D'Alembert z. B. took a naturalistic position according to which one finds God in nature. That is why the Encyclopédie , like many other works of the Enlightenment, was placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1759, and the state also took measures against individual authors and the spread of the work. However, the Encyclopédie also received support from government circles, for example from Ludwig's lover Madame de Pompadour , who appeared as protector, so that publication was initially permitted.

The forces of the old regime tried to bring the company down. Around 1752 the Jesuits and Jansenists allied themselves to take action against the "infidels" via the Sorbonne and the Parlement , the supreme court. The defense against this attack was a masterpiece that succeeded with the participation of the Pompadour, Voltaires and two ministers, probably also because in the meantime Frederick the Great had invited d'Alembert to Berlin to have the Encyclopédie published there. Now the booksellers warned of the impending losses and emphasized the advantages if the work was published in France. Minister Malesherbes , the liberal chairman of the supreme censorship authority and personal friend of many writers, submitted reports according to which the booksellers had nothing to fear. Further attacks on the Encyclopédie were also averted with backing from French government circles, although the royal privilege had been withdrawn after d'Alembert's article Genève ( Geneva ) in the seventh volume (1757) angered the Calvinist clergy there.

Subsequently, the text volumes 8 to 17 had to be published secretly in France. To disguise this, Neuchâtel in Switzerland was given as the place of publication. In order to forestall the censorship, Le Breton changed texts from the 8th volume on - behind the back of Diderot, who only noticed this afterwards and raved: "They murdered the work of twenty decent people [...] or had them murdered".

In the article sodomy, the Encyclopédie endorsed draconian punitive measures against homosexuals, with the addition that this should also apply to women and minors.

Censorship 1752

The first volume of the Encyclopédie was published in January 1752; the printed date of June 1751 on the title page is incorrect. The encyclopedia experienced the first repression carried out by state institutions in 1752. The occasion was the theological dissertation of Jean-Martin de Prades , reviewed by the Irish professor Reverend Luke Joseph Hooke , who in the end lost his office and dignity. On November 18, 1751 , he defended his work at the Sorbonne . But soon afterwards his dissertation for the doctor theologiae became a dubious loyalty to dogma - i. H. close to the Encyclopédie - suspected, so that the academic authorities subjected his work to scrutiny.

In his dissertation, de Prades had put forward a number of theses that led to a sharp argument with representatives of the theological faculty at Paris University. Among other things, de Prades had expressed doubts about the chronological sequence of events in the Pentateuch and compared the healing miracles of Jesus with those of the Greek god of healing Asclepius . Without naming his role models, de Prades made extensive use of the preface written by d'Alembert to the Encyclopédie , the Discours préliminaire , and the Pensées philosophiques by Diderot. De Prades was in personal contact with Diderot and had met with him several times for talks. On December 15, the commission of the Paris theological faculty dealing with the case determined that the theses expressed in the dissertation were to be rejected and that the writing itself fell under the censorship regulations. For the second volume of the Encyclopédie , published in January 1752, de Prades wrote an article about fifteen pages under the heading of certainty, certitude . De Prades' article was framed by an introduction and an endorsement by Diderot. Against the background of the dispute over his dissertation, the theologians expressed their indignation and accused de Prades of heresy . An arrest warrant was issued against de Prades, he fled to Holland and finally to Berlin. The two first volumes of the Encyclopédie , which had already been published , were banned on February 7, 1752, as were the remaining volumes. Chrétien-Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes , chief censor of the Censure Royale , intervened protectively.

Malesherbes diverted the crisis in such a way that only on February 2, 1752, with a council decree ( arrêts du Conseil ), passages in the text were identified in the first two volumes which "had a destructive effect on the royal authority and strengthened the spirit of independence and revolt and made it ambiguous Understood the foundations of error, moral corruption, irreligion and unbelief promoted ”. However , this had no effect on the distribution of the Encyclopédie , as the first two volumes had already been delivered to buyers or subscribers. The printing privilege was also not withdrawn. Malesherbes also received support in this matter from Madame de Pompadour .

Censorship between 1757 and 1759

It was the time of the Seven Years' War and the economic and political instability of the Kingdom of France, as well as the Crown's fear of conspiracy, rebellion and questioning of royal authority, which led, for example, to a decree of April 16, 1757 threatening everyone with death who wrote or printed against church and state. A public occasion offered the 5th January 1757. A stable assistant Robert François Damiens perpetrated on Louis XV. a knife attack. As a result of this same attack, the Enlightenment ideas were taken under general suspicion. The censorship authorities checked with increased vigilance, based on the April decree. Under the more acute censorship conditions and without official permission to print, the third volume could only appear in October 1753 with the tolerance of the Supreme Censorship Authority. The other volumes up to volume seven then appeared at regular annual intervals until 1757. Diderot announced the appearance of the eighth volume for the year 1758, but a total of eight years should elapse before the actual publication. On March 8, 1759, the Encyclopédie was placed on the index and the royal printing permission was revoked on the same day. At the end of April, Denis Diderot was threatened with a new arrest warrant, and Chrétien-Guillaume de Lamoignon de Malesherbes intervened as chief censor of the Censure Royale .

Change of editorship

The co-editor d'Alembert withdrew from the project in 1759. Louis de Jaucourt took his place in 1760 .

With the support of Malesherbes, a new privilege could be obtained for the table volumes so that they could appear openly in Paris.

Release dates

The publication, which began in 1751, was initially completed in 1772 with the 28th volume.

| frontispiece | 17 volumes of text | 11 table volumes |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Publishing successes

The Encyclopédie was a tremendous financial success. Together with six reprints in Switzerland and Italy , around 25,000 copies were sold by 1789 [?]. The Encyclopédie had up to 4,000 subscribers (an encyclopedia was already considered successful when around 2,000 copies were sold; around 1,500 subscribers were enough, for example, to finance the "Zedler" ).

Supplementary volumes

The publisher Charles Joseph Panckoucke , 1770 holders of the rights to the Encyclopaedia, produced a total of seven Suppléments (additions): 1776 two text volumes, 1777 two more volumes of text and a picture board band and in 1780 one of Pastor Pierre Mouchon elaborate two-volume register ( Table analytique et raisonnée de l'Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers ). The suppléments were published by Jean-Baptiste Robinet .

Follow-up works

The Journal encyclopédique by Pierre Rousseau appeared from 1756 to 1793. The Encyclopédie d'Yverdon , 58 volumes, edited by Fortunato Bartolomeo de Felice, appeared from 1770 to 1780.

With the Encyclopédie méthodique , Panckoucke undertook a revision of the Encyclopédie by publishing specialist dictionaries ( dictionnaires ) on initially 27 and finally more than 50 subject areas - a structure that also corresponded to the structure of the modern university, consisting of independent faculties and institutes. The first volumes appeared in 1782, and when Panckoucke's son-in-law Henri Agasse bought the company in 1794, there were more than 100 volumes. When Agasse died in 1813, his wife continued to run the company. The last volume appeared in 1832. Now 206 volumes with their own title page comprised 125,350 pages of text and around 6,300 tables. The work brought the publisher fame, but hardly any financial gain: in the wake of the revolution, the number of subscribers had fallen dramatically.

Translations into German

- introduction

- Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert: Introduction to the French encyclopedia of 1751 (= Philosophical Library. Volume 140, a – b, ZDB -ID 536403-6 ). 2 volumes. Edited and explained by Eugen Hirschberg. Meiner, Leipzig 1912.

- Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert: Introduction to the encyclopedia of 1751 (= Philosophical Library. Volume 242). Edited and introduced by Erich Köhler. Translated from the French by Annemarie Heins. Meiner, Hamburg 1955 (2nd, revised edition. Ibid 1975, ISBN 3-7873-0336-7 ).

- (= Fischer pocket books. Philosophy 6580). Unabridged edition. Edited and with an essay by Günther Mensching . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-596-26580-0 .

- (= Philosophical Library. Volume 473). Reviewed and edited with an introduction by Günter Mensching. Meiner, Hamburg 1997, ISBN 3-7873-1188-2 .

- Jean-Baptiste le Rond d'Alembert: Introductory treatise to the encyclopedia (1751). Newly translated on behalf of and with the assistance of the working group on the history of philosophy at the German Academy of Sciences in Berlin. With an introduction and comments by Georg Klaus. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1958.

- selection

- Jean Le Rond d'Alembert: Encyclopedia. A selection (= Fischer pocket books. Philosophy 6584). Edited and introduced by Günter Berger. With an essay by Roland Barthes . Translated from the French by Günter Berger. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-596-26584-3 .

- Revised new edition: Denis Diderot - Jean-Baptiste le Rond d´Alembert: Encyclopedia. A selection (= Fischer Klassik 90521). Edited and introduced by Günter Berger. Translated from the French by Günter Berger, Theodor Lücke and Imke Schmidt. S. Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 978-3-596-90521-8 .

- Denis Diderot: The Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot. A selection (= The bibliophile paperbacks. Volume 389). Edited and with an afterword by Karl-Heinz Manegold. Harenberg, Dortmund 1983, ISBN 3-88379-389-2 .

- Denis Diderot: Encyclopedia. Philosophical and political texts from the "Encyclopédie" as well as prospectus and announcement of the last volumes (= dtv 4026 Scientific Series ). With a foreword by Ralph-Rainer Wuthenow . Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 1969 (excerpt from the 1961 edition).

- Denis Diderot: Philosophical Writings. Volume 1. Translated from the French by Theodor Lücke. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1961.

- Philosophical and political texts from the "encyclopédie". A selection from the “Philosophical Writings”. As well as prospectus and announcement of the last volumes. With a foreword by Ralph Rainer Wathenow ed. and translated from the French by Theodor Lücke (1961) . Munich 1969.

- Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi et al. (Translator): Scene of the arts and crafts or full description of the same. Made or approved by those gentlemen of the Academy of Sciences in Paris. Translated into German and annotated ... 21 volumes. Rüdiger et al., Berlin et al. 1762–1805.

- Anette Selg, Rainer Wieland (ed.): The world of the Encyclopédie. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-8218-4711-5 .

- Manfred Naumann (Ed.): Diderot's Encyclopedia. A selection . Reclam Verlag, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-379-01740-X ,

Illustrated books

- Jürgen Dahl (Hrsg.): Youth of the machines. Images from the encyclopedia by Diderot and d'Alembert (1751 to 1772) . Langewiesche-Brandt publishing house, Ebenhausen 1961.

- Diderot's encyclopedia. The panels 1762 to 1777 . Four volumes and register tape in the small octave format (16.5 cm) instead of folio (39 cm). Südwest Verlag, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-517-00672-6 .

- Roland Barthes , Robert Mauzi, Jean-Pierre Seguin: L'univers de l'Encyclopédie . Les Libraires Associés publishing house, Paris 1964.

- A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry, Vol. 1 . Dover Publishers, 1959, ISBN 978-0-486-22284-4 .

- A Diderot Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trades and Industry, Vol. 2 . Dover Publishers, 1993, ISBN 978-0-486-27429-4 .

- Diderot & D'Alembert: Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaure Raisonné des Sciences. Paris 1751–1772: Anatomy - Surgery. Facsimile print based on the original from 1751–1772, Antiqua-Verlag, Lindau i. B. 1978, ISBN 3-88210-002-8 .

literature

- Philipp Blom : The sensible monster. Diderot, d'Alembert, de Jaucourt and the Great Encyclopedia (= The Other Library. Volume 243). Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-8218-4553-8 .

- Phillip Blom: Encyclopédie. The Triumph of Reason in an unreasonable Age. Fourth Estate, London et al. 2004, ISBN 0-00-714946-8 .

- Robert Darnton : A Little History of the Encyclopédie and the Encyclopedic Spirit. In: Anette Selg, Rainer Wieland (ed.): The world of the Encyclopédie. Eichborn, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-8218-4711-5 , pp. 455-464.

- Robert Darnton: Shiny business. The dissemination of Diderot's Encyclopédie or: How do you sell knowledge for a profit? Wagenbach, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-8031-3568-0 (partial translation of the English original edition).

- Robert Darnton: Philosophers trim the tree of knowledge. The epistemological strategy of the Encyclopédie. In: Robert Darnton: The Great Cat Massacre and other Episodes in French Cultural History. Basic Books, New York NY 1984, ISBN 0-465-02700-8 , pp. 191-213 (Reprinted edition. Penguin Books, London et al. 1991, ISBN 0-14-013719-X ).

- German: Robert Darnton: Philosophers pruning the tree of knowledge: The epistemological strategy of the Encyclopédie. In: Robert Darnton: The great cat massacre. Forays into French culture before the revolution. Translated by Jörg Trobitius. Hanser, Munich et al. 1989, ISBN 3-446-14158-8 , pp. 219–245.

- Robert Darnton: The Business of Enlightenment. A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie. 1775-1800. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 1979, ISBN 0-674-08785-2 .

- Jacques Proust : Diderot et l'Encyclopédie (= Bibliothèque de l'Évolution de l'Humanité. Volume 17). Michel, Paris 1995, ISBN 2-226-07862-2 .

- Jean de Viguerie: Histoire et dictionnaire du temps des Lumières. Laffont, Paris 1995, ISBN 2-221-04810-5 .

- Volker Mueller: Denis Diderot's idea of the whole and the 'Encyclopédie' Neu-Isenburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-943624-03-8 .

- Ulrich Hoinkes: The great French encyclopedia by Diderot and d'Alembert. In: Ulrike Haß (ed.): Large encyclopedias and dictionaries of Europe , De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-019363-3 , pp. 117-136

- swell

- Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers. Mis en ordre & publié by M. Diderot, de l'Académie Royale & des Belles-Lettres de prusse; & quant à la Partie Mathematique, by M. d'Alembert, de l'Academie Royale des Sciences de Paris, de celle de Prusse, & de la Societé Royale de Londres. Paris 1751-1780. (Reprint in 35 volumes: Frommann-Holzboog, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1968–1995, ISBN 978-3-7728-0116-7 ).

- L'Encyclopédie de Diderot et d'Alembert. Edition DVD. Redon, Marsanne 2000, 2002, 2004 (the full Encyclopédie on DVD-ROM).

- J. Assézat, Maurice Tourneux (ed.): Œuvres complètes de Diderot . 20 volumes. Garnier, Paris 1875–77.

- Tools

- Frank A. Kafker, Serena L. Kafker: The encyclopedists as individuals. A biographical dictionary of the authors of the Encyclopédie (= Studies on Voltaire and the eighteenth century. Volume 257). Voltaire Foundation at the Taylor Institute, Oxford 1988, ISBN 0-7294-0368-8 .

- John Lough : The Encyclopédie. Slatkine, Geneva 1989, ISBN 2-05-101046-3 ( limited online version in Google Book Search - USA ).

See also

- Encyclopaedist (Encyclopédie) - the 140 encyclopedists known by name

- History and development of the encyclopedia

- Aguaxima - a famous entry in the Encyclopédie

Web links

- The Encyclopédie online (French)

- ENCCRE - Édition Numérique Collaborative et Critique de l'Encyclopédie (scans, full texts and collaborative critical commentary) of the Académie des Sciences

- Online version of the first edition of the Encyclopédie (ARTFL project of the University of Chicago)

- ARTFL project of the University of Chicago (additional information)

- Encyclopédie de Diderot (systematic overview, online edition and research option)

- The Encyclopédie online

- University of Michigan Library: Collaborative translation project (parts only, with list of authors)

- For the introduction

- Ulrike Spindler: "The Encyclopédie by Diderot and d'Alembert"

- Recording of a 45-minute broadcast about the Encyclopédie , BBC Radio 4, 2006 (English)

- Special topics

- Natale G. De Santo; Carmela Bisaccia; Massimo Cirillo; Gabriel Richet: Medicine in the Encyclopédie (1751-1780) of Diderot and d'Alembert. In: J. Nephrol. Volume 24 (S17), 2011, pp. S12-S24.

Individual evidence

- ↑ haraldfischerverlag.de: About the Encyclopédie ( Memento of the original from September 24, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (accessed February 25, 2009).

- ^ Translation by Irene Schwendemann (Ed.): Major works of French literature. Individual presentations and interpretations. 4th edition. Munich 1983, p. 191.

- ↑ Denis Diderot: Lettres à Sophie Volland . In: J. Assézat, M. Tourneux (eds.): Œuvres complètes de Diderot . tape XIX . Garnier, Paris 1876, p. 140 ( letter of September 26, 1762 ).

- ↑ More detailed in: Robert Darnton: The Great Cat Massacre and other Episodes in French Cultural History. Basic Books, New York 1984, ISBN 0-465-02700-8 , pp. 191-213.

- ↑ ub.uni-konstanz.de: Diderot - d'Alembert: Encyclopédie (accessed on February 25, 2009).

- ↑ Expanded in 1702, ten editions by 1760.

- ↑ a b c d e f historicum.net: Publication history of the Encyclopédie (accessed on February 26, 2009).

- ^ Robert Darnton: The Business of Enlightenment. A Publishing History of the Encyclopédie. 1775-1800. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge MA et al. 1987, ISBN 0-674-08786-0 .

- ↑ Frank Wald carrots: The material Bibliography the Encyclopédie: originals and pirated editions. In: Dietrich Harth , Martin Raether (Ed.): Denis Diderot or the ambivalence of the Enlightenment. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1987, ISBN 3-88479-277-6 , pp. 63-89.

- ^ Johanna Borek: Denis Diderot. Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-499-50447-2 , p. 58.

- ↑ Pierre Lepape: Denis Diderot. A biography. Campus-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1994, ISBN 3-593-35150-1 , p. 198.

- ^ Robert Darnton: Shining Business. The spread of Diderot's Encyclopedia or: How do you sell knowledge for a profit? 1993, p. 22.

- ↑ Philipp Blom: The reasonable monster. 2005, p. 166.