Leader of the undecided

The Leader of the Undecided is the main philosophical work of the medieval Jewish scholar Maimonides , which, based on Judeo- Kalamite theology and peripatetic - Avicennic philosophy, takes a stand on fundamental religious and philosophical questions. First and foremost, it should serve to prove that the Jewish tradition, when correctly interpreted - that is, taking into account the inevitable imagery of language, including that of biblical speech - corresponds to the knowledge of reason.

The work had the greatest influence on the thinking of Jewish posterity and also served as a guideline for Arab and Christian philosophers and theologians. From an internal Jewish perspective, Maimonides was fiercely fought against by orthodox opponents in his time (" Maimonides controversy", "anti-Maximunists"), not least because his attempt to reconcile the Bible with philosophy was understood as a way away from the Bible and towards philosophy.

Origin and title

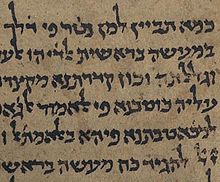

The book was published towards the end of the 12th century by Maimonides - originally for his enthusiastic disciple Joseph ibn Sham'un - in Judaeo-Arabic under the title Dalālat alḥā'irīn דלאל̈ה אלחאירין Arabic دلالة الحائرينwritten, but is mainly under the Hebrew title More Nevuchim ("Teacher of the ashamed or indecisive, confused"מורה נבוכים) known.

Classification of the book

After the introductory foreword, the Leader of the Undecided is divided into three books:

- The first part deals with various traditional predicates (God has a hand and other organs, he acts in a wide variety of ways, etc.) and argues - often using linguistic or religious-historical arguments - against a literal reading that would imply a humanization of God ( anthropomorphism ) . This is followed by a developed doctrine of attributes (chap. 50ff) and a discussion of various theological problems, in particular a description and criticism of the Islamic Kalam (chap. 70f).

- The second part discusses the creation of the world , proofs of God , divine providence and the knowledge of God including prophecy .

- The third part begins with a discussion of cosmology which is linked to an interpretation of the Ezekiel vision ( Ma'asse Merkava ). This is followed by reflections on providence and free will as well as justifications of the divine commandments and a mediation of theoretical and practical philosophy.

Purpose of the book

Maimonides wrote his work for readers who hold fast to their faith and practice it, but at the same time have a degree in philosophy and are confused by the literal meaning of biblical expressions in which God is described with human features. To such a reader, Maimonides shows that these difficult expressions have a second figurative meaning in addition to their literal meaning, and that this second meaning applies to God. In addition, Biblical parables that are difficult to understand are explained in the Leader of the Undecided . The book thus serves the philosophical understanding of the holy scriptures or, as the author puts it, “the science of the law in its true sense” or “the secrets of scripture” (preface to the leader of the indecisive ).

The book is expressly not written for a mass audience. According to the Mishnah ( Chagiga 2: 1) it is forbidden to teach even one person in the introduction to the book of Ezekiel unless that student is wise and able to understand the material himself. Maimonides qualifies the prohibition as binding halacha and justifies this in his Mischna commentary with the philosophical point of view valid at the time: teaching an abstract material could lead a student to disbelief, provided the material is beyond his grasp.

This prohibition against the publication of views on mystical questions posed a problem for the author. He was forced to write a work dealing with esoteric topics, which is actually forbidden according to Jewish tradition. Maimonides solved the problem by using certain literary figures . First he dedicated his work to his student Joseph ibn Sham'un, who moved from Cairo to Baghdad after studying with his master . In formal terms, then, the book is a personal communication to a single student. In addition, Maimonides describes the spiritual development of Joseph in the introductory letter of dedication and shows that his student had acquired enough philosophical wisdom to be able to think for himself and thus meet the conditions to be able to devote himself to esoteric disciplines.

Maimonides was of course aware that other people would also read his book, and therefore had to resort to other means. In the style of Islamic philosophers , he wrote his book in an enigmatic style. When dealing with a particular topic, he comes across contradicting statements at various points in the book. In the introduction to the leader of the undecided, he lists seven different types of contradictions in literary works and expressly states that he will make use of two of them. It is up to the reader to find the contradictions in the course of reading.

content

God

God is Maimonides' first philosophical theme. The author dedicates most of the first 49 chapters of the first part of the Leader of the Undecided to him . His exegesis begins with explanations of the term image of God , which is used in the creation story . Maimonides rejects the argument that God must also have a body, since man was created in the image of God. The author shows that the Hebrew term zelem ("image, image") always indicates a spiritual quality, an essence . That is why the image of God in man is the human essence - that does not mean physical equality, but human reason.

In the next 11 chapters, Maimonides turns to the question of divine attributes (Part I, Ch. 50-60). The Bible enumerates numerous attributes of God, but also describes him (in Shema Yisrael ) as the only one. How can a multitude of attributes be ascribed to God as the only being? In medieval scholasticism , a distinction is made between essential and accidental attributes. Essential, essential attributes are closely related to the essence, such as the existence of life. Accidental attributes, such as anger or grace, are independent of the essence, and changing them does not affect the essence. Maimonides concludes that accidental attributes must be understood in terms of an action; that is, when God is described as gracious, he acts with grace. Essential attributes, on the other hand, are to be interpreted in the sense of a negation ; this means that if God is described as existing, he is not non-existent ( negative theology ).

Before Maimonides, Islamic and Jewish scholars of the Kalam tried to use arguments to prove the existence, unity and incorporeality of God and the creation of the world. Maimonides summarizes these arguments in order to refute them (Part I. Chapters 71-76). In the case of the creation of the world, he is of the opinion that the evidence of the creation or the eternal existence of the world lies beyond the limits of the human mind.

Creation

In the second part of his work, Maimonides first deals with the incorporeal intelligences that he identifies with the angels (Part II, Chapters 2–12), and then with creation (Part II, Chapters 13-26). On the latter topic, he lists three theories of the creation of the world: creation out of nothing , which is represented in the Torah , that of Plato and other Greek philosophers, according to which God created the world from pre-existing matter , and the theory of Aristotle , according to which the world is eternal. Much of the discussion is devoted to the claim that the evidence of Aristotle and his successors about the eternity of the world is not correct evidence. Using an analysis of Aristotelian texts, Maimonides tries to show that Aristotle himself did not see his arguments as conclusive evidence, but only wanted to show that eternity is more plausible than a creation out of nothing. Maimonides takes the position that plausible arguments can be made for both creation and eternity of the world. After examining the two-sided arguments, however, he comes to the conclusion that creation is more likely than eternity, and makes the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo his own. Another reason for this is that Scripture itself teaches creation. For Maimonides, the principle of the creation of the world is the most important thing after God's unity, since among other things, it can explain the possibility of miracles.

When the world is created, will it come to an end at some point in the future? Maimonides denies this question and adds that the future indestructibility of the world is also taught in the Bible (Part II, Chapters 27-29). This part ends with an explanation of the creation account at the beginning of Genesis and a discussion of the Sabbath , which in part also represents a reminder of the work of creation.

prophecy

After Maimonides had casually compared the nature of prophetic experience with intellectual enlightenment in the foreword , in Part II, Chap. 32–48, focusing on their psychological and political function. First, he enumerates three theories about the possible emergence of prophetic ability: Naive believers hold the opinion that God arbitrarily chooses someone to be a prophet; Philosophers hold that prophetic faculties arise when man's natural faculties, especially his intellect , reach a high level of development; Finally, the Bible assumes the same development of natural faculties, but adds a dependency on God who could prevent one from the activity of prophecy if he so desired. According to this latter view, God has a negative rather than a positive role in prophecy.

Maimonides describes prophecy as a divine emanation which, through the mediation of the active intellect, first reaches the spiritual abilities and then the imagination of the human being. A highly developed imagination has little influence on the prophet's experience of enlightenment, but is of outstanding importance for his political function. In accordance with the views of Islamic Aristotelians, especially al-Fārābī , Maimonides sees the Prophet as a statesman who brings the law to his people and exhorts them to observe it. This conception of the prophet as a statesman is based on Plato's idea of the philosopher king , who, according to the statements in the Politeia, establishes and administers the ideal state. Maimonides sees the main function of all prophets beside and after Moses in exhorting people to keep the law of Moses . Therefore, the prophets needed imaginative language and parables that would appeal to the imagination of the masses. Maimonides describes three types of personality: the philosopher who only uses his intellect; the common statesman who relies only on his imagination; and the Prophet who uses both.

Nature of evil

Maimonides begins the third part of his work with a philosophical interpretation of the divine chariot Merkaba and identifies it with metaphysics , while the history of creation is equated with physics (Part III, Chapters 1–7). He then turns to practical philosophy and begins by explaining the nature of evil (Part III, Chapters 8-12).

The author accepts the doctrine of the Neoplatonists and other monists that evil is not an independent principle, but rather a lack of good or the absence of good . He has to accept this point of view, because with the acceptance of an independent principle of evil the uniqueness and omnipotence of God would be excluded. Maimonides distinguishes three types of evil: natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes , which are not under the control of man; social evils such as wars , and personal evils such as the various human vices , both of which can be controlled by humans. Since natural disasters are rare, most of the evils in the world are caused by humans and can be avoided with proper practice. Maimonides also opposes the view that the world is essentially bad, arguing that if one gets away from preoccupation with one's personal pains and difficulties and looks at the world by and large, it is not bad but good .

providence

In Part III, Chap. 16–21, Maimonides discusses divine omniscience and then turns to the related topic of Divine Providence . He differentiates between general providence, which refers to the laws of nature , and individual providence, that is, God's concern for the well-being of the individual. He enumerates four theories of Providence which he rejects: the theory of Epicureanism , according to which everything that happens in the world is based on chance ; the theory of Aristotle (in reality that of his commentator Alexander of Aphrodisias ) that there was only general, not individual, Providence; that of the Islamic Asharites, a school of the Kalam , according to which the divine will rules everything - thus the individual providence would extend to everything created - animate and inanimate ; and finally the theory of the Mutazilites , another school of the Kalam, according to which individual providence extends to animals, but not to inanimate objects. Maimonides also rejects the principle of testing out of love , which is advocated by some Geonim and according to which God lets a righteous person suffer in order to reward him in the hereafter , as unjust.

After all, he takes as his personal point of view that there is individual providence and that it is determined by the extent of the development of personal intellect. The more developed a human intellect, the more it is subject to divine providence. In chap. 22 and 23 of Part III, Maimonides uses this theory to explain in his interpretation of the book of Job the attitudes of the persons appearing there towards the divine providence discussed above.

The Law of Moses

In the concluding part of his work (Part III, Chapters 26-49) Maimonides attempts to explain the reasons for the Law of Moses and its individual regulations. He refers to a distinction from the group of Mutazilites, especially from Saadia Gaon . Accordingly, a distinction is made between two categories within divine law: rationally explainable commandments, such as the prohibitions of murder and theft , which do not require revelation to understand ; and revealed commandments, such as prayer and the observance of holidays , which are neutral from the standpoint of reason and can only be recognized by revelation. Maimonides interprets this point of view as an indication that revealed commandments flow less from God's wisdom than from His will. On the other hand, he postulates that all divine commandments are based on divine wisdom, although he distinguishes between easily understandable commandments (Hebrew mischpatim ) and difficult to understand commandments (Hebrew chukkim ) and admits that some special commandments cannot be reasonably justified and are based exclusively on God's will .

According to Maimonides, two goals are pursued with the Law of Moses: on the one hand, the spiritual or spiritual well-being of the person, on the other hand, his physical well-being, which the author understands as moral well-being. The latter is achieved through political and personal integrity , the former through true beliefs. Maimonides distinguishes between true and necessary beliefs. The true principles include God's existence, oneness, and incorporealness, which must be accepted by everyone regardless of their spiritual abilities. For example, it is necessary to have the idea that God persecutes those who disobey him with his anger. Such ideas primarily have a political function and are primarily intended for the average person who only accepts a law if he is promised a reward or a punishment for non-compliance. A philosopher can dispense with such necessary ideas and obey the divine law solely because it corresponds to the truth and the law, without regard to an immediate reward.

The book closes with an additional section on perfect worship of God and the perfecting of man.

Eschatology

Questions of eschatology are hardly dealt with in the Leader of the Undecided , although Maimonides gives them a lot of space in other works. In his remarks on the Messiah , the messianic time, the resurrection of the dead and the world to come , he follows traditional Jewish traditions. In the way that is typical for him, he tries to use as few supernatural reasons as possible to explain these phenomena . He describes the Messiah as an earthly king from the house of David , who will bring the Jews back to their land, but above all will create peace and quiet all over the world and thus facilitate the full observance of God's commandments. The Messiah would die in old age and be followed by his son, who in turn would be followed by his son, and so on. In his letter to the Jews in Yemen (Iggeret Teman) Maimonides even calculated the year of arrival of the Messiah, although he was generally averse to speculations of this kind.

In his description of the world to come , Maimonides postulates only a spiritual, but not a physical, life after death, the focus of which is on contemplation of God. He usually speaks of disembodied intelligences in the plural , thereby implying an individual immortality ; however, there are also passages that point to collective immortality. This would be understood to mean that there is only one spirit for all humanity in the world to come.

Impact history

The work was translated into Hebrew twice in the Middle Ages under the title More Newuchim :

- The first translation was written by Samuel ibn Tibbon from the Ibn Tibbon family of translators , who was able to rely on detailed instructions from the author in his work.

- The second translation comes from Juda al-Charisi (1170-1235), a Spanish-Jewish writer. Compared to Ibn Tibbon's work, it is more open, but was translated into Latin (Augustus Justinianus, published in Paris in 1520) and Spanish (Pedro de Toledo) and thus influenced the Christian world of thought.

For Maimonides, the Hebrew translation of his Arabic written works was of the utmost importance. When some rabbis in Lunel asked him in a letter to translate The Leader of the Undecided into Hebrew, he replied that he wished he were young enough to do so.

Isaak Abrabanel , Shem Tov ibn Falaquera, and Solomon Maimon published comments on the Leader of the Undecided . Among the more modern Jewish thinkers who were influenced by this work are, in addition to Moses Mendelssohn , the father of Haskala , Nachman Kromal , Samuel David Luzzatto (who opposed Maimonides' rationalism), Salomon Ludwig Steinheim , Hermann Cohen and Achad Ha 'on . The most important contemporary criticism in the context of the Maimonides dispute came from Abraham ben David von Posquières , who mainly accused Maimonides of negligence in citing authoritative sources. Later, numerous Jewish scholars turned against the penetration of Aristotelian ideas into the Jewish spiritual world, including above all the Spanish-Jewish scholar Chasdaj Crescas (1340–1411), whose main work Or Adonai or Or Haschem exerted a significant influence on Spinoza (see: Manuel Joël , Contributions to the History of Philosophy , Breslau 1876).

Maimonides had a significant influence on scholastic thought since the 13th century . Its main representative, Thomas Aquinas , in particular , dealt critically with Maimonides in both the Summa theologica and the Summa contra gentiles . On the one hand, he accepted his thesis that the temporal creation of the world could neither be proven nor refuted by philosophical argument; on the other hand, he opposed Rabbi Moyses' radical rejection of all divine attributes which people use to attempt to explain divine existence from their experience in the created world. The attempt of Maimonides to combine the cosmology of the Peripatetic with the belief in the creation story according to Genesis met with open ears with Albertus Magnus . Research by Josef Koch published in 1928 shows that Meister Eckhart was also heavily influenced by Maimonides. Even De docta ignorantia of Nicholas of Cusa contains passages from the Dux neutrorum , the Latin version of the Guide for the Perplexed . Other scholastics who dealt with Maimonides are Alexander von Hales , Wilhelm von Auvergne and Duns Scotus . Aegidius Romanus wrote a treatise around 1270 under the title Errores philosophorum ("The errors of the philosophers"), the 12th chapter of which is devoted to a refutation of Maimonides' views.

literature

Editions, translations

- Husain Ata'i (ed.): Dalalat al-ha'irin. Üniv., Ankara 1974 (Arabic transcription).

- Agostino Giustiniani, Augustinus Justinianus (ed.): Rabbi Mossei Aegyptii Dux seu Director dubitantium aut perplexorum , Paris 1520; ND by Kurt Flasch , Frankfurt: Minerva Journals 1964, ISBN 3-86598-129-1 (text base: Hebrew translation of Juda al-Charisi ; first complete Latin translation; edited in the context of Erasmus ).

- Salomon Munk (ed.): Le Guide des égarés. Traité de théologie et de philosophie par Moïse ben Maimoun dit Maïmonide. Réimpression photomechanique de l'édition 1856–1866. Zeller, Osnabrück (critical edition of the Judeo-Arabic text with French translation and commentary).

- Shlomo Pines (Ed.): The guide of the perplexed. Univ. of Chicago Pr., Chicago 1963 (the commonly used translation).

- Leader of the undecided . Translator (and comment) v. Adolf Weiß, Berlin 1923/24; 3. Aufl. Meiner, Philosophische Bibliothek 184a-c , Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-7873-1144-0 ( online edition of the first edition, UB Frankfurt ).

- Y. Kafih (Ed.): Moreh Nevukhim. Mosad ha-Rav Kook, Jerusalem 1972 (Hebrew translation).

- Michael Schwarz (Ed.): Moreh Nevukhim. Tel Aviv University Press, Tel Aviv 2002 (Hebrew new edition in common use).

Secondary literature

- Manuel Joël: The philosophy of religion of Moses b. Maimon , 1859.

- Moses b. Maimon, his life, his works and his influence , I. 1908, II. 1914 (therein: Bloch, characteristics and table of contents of the Moreh Nebuchim ).

- Israel Efros: Philosophical Terms in the Moreh Nebukim , New York 1924.

- Encyclopedia Judaica , Vol. 11, pp. 767-777.

- Fritz Bamberger : The system of Maimonides. An analysis of the More Newuchim from the concept of God. Schocken, Berlin 1935.

- Society for the Promotion of the Science of Judaism (ed.): Maimonides. His life, works and influence , 1971.

- Aviezer Ravitzky: Samuel Ibn Tibbon and the Esoteric Character of the Guide of the Perplexed . In: Association for Jewish Studies (AJS) Review , Volume 6, 1981, pp. 87–123.

- Friedrich Niewöhner , Maimonides. Enlightenment and Tolerance in the Middle Ages , 1987.

Web links

- Jacob Tuesday: Maimonides' Guide for the Perplexed : A Bibliography of Editions and Translations

- More Newuchim - Excerpts of the Guide to Indecisive Translation (translation by Dr. Adolf Weiss)