History of ethics

Under the history of ethics , the basic philosophical positions in the field of general ethics are presented from a historical perspective. For a systematic overview see there.

Prehistory and ancient civilizations

Even with the prehistoric societies it must be assumed that ethical rules of behavior have developed in them, as observations on primitive societies show. These societies are generally based on religion , and prohibitions can often be recognized by taboos .

For the early advanced civilizations too, religion is of decisive importance for the development of social ethos . In ancient China, for example, classification in the Tao , the principle of world order, is the top priority. The Vedic religion of India knows a moral law ruling the world, which as an impersonal greatness even stood above Varuna , the world creator. In the Babylonian religion , the ethical commandments are traced back to Shamash , the god of justice, who is also considered the author of the Codex Ḫammurapi , the oldest traditional collection of laws. The Talion is introduced as a legal principle, which calls for retribution of like for like.

Pre-Christian antiquity

In ancient Greece the device mythological tradition as the basis of ethics increasingly coming under fire. For the first time ethics emerged as a philosophical discipline. While in archaic societies the entire social order was thought to be determined by the gods or one god, the individual now comes to the fore. A sensible, generally visible legitimation of human practice is required. The sophists question the laws of the polis and contrast them with natural law . The focus is on questions about the good life and the highest good . The realization of the good life is first tied to the social community. With the collapse of the polis as a democratic institution, this reference is abandoned. In the Stoa this leads on the one hand to a cosmopolitan ethos and the idea of a universal natural law, but on the other hand also to a retreat into the interior of the ethical subject.

Onto-teleological approaches

This classic teleological approach , also known as the ethics of striving , is represented primarily in the heyday of the Greek classical period and in Hellenism . It assumes that every natural object has an inherent striving to achieve a goal that is inherent in its nature or essence. The intrinsic goal is achieved in that the object perfects its specific disposition and thus develops a natural final shape. It does not matter whether the object in question is an inanimate thing, a plant, an animal or a rational being. Objects in this sense are not only natural objects; also the social or political community, history or the entire cosmos can be understood as teleological entities.

Humans also have their own goals, which they achieve by perfecting their specific systems. In his nature there is already a very specific target figure, towards which he develops. However, unlike inanimate objects, plants or animals, humans are not viewed as being entirely determined by their natural properties and objectives. He must also participate in the realization of his "telos" himself to a certain extent.

The onto-teleological approach demands that humans act and live in a way that corresponds to their essential nature, in order to perfect their species-specific disposition in the best possible way. Since humans have a certain amount of freedom, they can also miss their target.

A distinction between moral correctness and extra-moral goodness makes no sense in the context of onto-teleological ethics. Although the disposition of external goods can play a role, it is not these goods that are primarily sought. The good that is most important is a certain way of acting, namely doing good itself.

Plato

With Plato , ethics was not yet developed as a completely separate discipline. It is closely related to metaphysics .

In the early Platonic dialogues , the question of the “essence” of virtues (“bravery”, “justice”, “prudence” etc.) is central. The various attempts to answer these questions lead to aporias , since in Plato's understanding the question of the good is placed before them. So is z. For example, the definition of bravery as "perseverance of the soul" is not appropriate, since there are also "bad" forms of perseverance.

What is good is answered in detail by Plato in the " State ". The question of the ideal state leads him to the question of what knowledge enables its rulers to exercise their rule correctly and fairly. This is the insight into the idea of the good . Without it, all knowledge and possessions are ultimately useless. Plato differentiates the good from the terms pleasure and insight . The good cannot be the same as the pleasure, since there are good and bad pleasure. But also not every random insight is identical with the good, only the insight into the good.

In the parable of the sun , the good is further illustrated by an analogy . The light of the sun gives the objects their visibility and enables us to see the objects. In addition, the sun represents the basis of existence for all life. Analogously, the idea of the good is the cause of the knowledge of things as well as of our knowledge. It is also the reason that things are what they are. It is the principle of all ideas and belongs to a higher order. Only through the good do things acquire their own being and essence.

For Plato, the knowledge of the good is not only the prerequisite for the knowledge of the essence of virtues - which was at the center of his early dialogues - but for the essence of all things. Because only when a person knows what a thing is “good” for, ie what its goal ( telos ) is, he is also able to recognize his true “essence”.

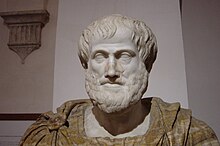

Aristotle

Aristotle is considered to be the classic representative of the onto-teleological approach. His ethics starts with the concept of the highest good . This must meet the following criteria:

- It has to be self-sufficient, that is, when one is in possession of this property, one must no longer need any other things

- It must be chosen for itself and never for the sake of anything else

- It is not increased by adding another good

According to the general opinion, these criteria are fulfilled by eudaimonia ( happiness ). However, there is controversy over what happiness is.

According to Aristotle, man can achieve happiness by trying to realize his specific “ ergon ”. The word " ergon " means the specific function, task or performance of a thing. In order to answer the question about the " ergon " of the human being, Aristotle falls back on the various faculties of the human soul:

- it has the life-sustaining abilities of nutrition and growth: however, these do not represent a specific human achievement, because they can also be found in all other living beings

- it has the faculty of sensory perception: this faculty is also found in other living beings

- it has the ability of reason ( logos ): this is the ability peculiar to man, because no other living being has this ability.

According to Aristotle, there are two different parts in the human soul that have to do with reason:

- the part that is itself reasonable or has reason

- the part that has no reason. This, in turn, is divided into a vegetative part (urge to eat, need for sleep, etc.) and a part that is able to listen to reason and obey it (emotions, non-rational desires, etc.). The latter is usually called aspiration.

The human ergon we are looking for now consists in activating the rational faculty of the two parts of the soul, that is to say, to transfer it from potentiality ( dynamis ) to actuality ( energeia ) ( act-potency theory). This specifically human achievement is achieved when the soul is in an “excellent” state, which Aristotle calls the term “ arete ” ( virtue ).

According to Aristotle, according to the two parts of the soul that can be called reasonable, two kinds of virtues can be assigned. The dianoetic or intellectual virtues correspond to the rational part of the soul, the ethical or character virtues to the unreasonable part of the soul .

This approach gives Aristotle's understanding of how perfect happiness can be achieved.

The best way of life is the “theoretical” or “contemplative” ( bios theôretikos ). In it the highest part of the human soul, reason, can be developed. According to Aristotle, however, such a life is higher than it is due to human beings as human beings and is actually only available to the gods. In addition, people are forced to deal with their external environment. Thus, for Aristotle, only the “political” ( bios politikos ) remains as the second best form of life . This enables character virtues to develop when dealing with other people.

Consequentialist -teleological approaches

Even in antiquity, there were ethical approaches that no longer assumed a final, predetermined expediency of human existence or the world. Her focus on the moral qualification of actions was directed exclusively to their consequences with regard to a "telos" understood as a benefit.

Epicurus

The Epicurean ethics , which was conceived as a weighty counter-project during the heyday of classical teleological ethics, expressly rejects any ultimate purpose of human existence or the world.

The desire ( hedone ) is explained by Epicurus for the sole content of the good life. He differentiates between two types of pleasure: a "kinetic" (moving) pleasure on the one hand and a "catastematic", i.e. H. pleasure in the other connected with the natural state.

The kinetic pleasure separates Epicurus out as a candidate for a good life. It is based on a constant alternation of states of unpleasure and pleasure and must therefore also affirm discomfort as a condition of its possibility. It also always harbors the danger that needs are constantly being satisfied beyond what is sensible and thus new needs are created. This kind of desire for pleasure is potentially excessive and, contrary to its original intention, threatens to become a constant source of discomfort.

The katastematische pleasure is the highest form of pleasure and the goal of life. It is achieved through the state of unneeded peace of mind ( ataraxia ). This is endangered by pain and fear. That is why Epicurus sees the task of ethics in the well-founded dissolution of unfounded fears. Epicurus sees four fears that are ultimately unfounded as central.

- The fear of (this-worldly) punishment from God: Epicurus considers it unnecessary to explain the natural course of the world through the intervention of gods. Rather, these exist “perfectly” and “blissfully” without being interested in such interventions.

- The fear of death: Epicurus defines "life" as a certain mixture of atoms, while death is the mere undoing of that mixture. Since for him states of consciousness, thus pain and our experience in general, necessarily depend on this mixture, there is no reason to fear death. As long as we are alive, death is not there, when death is there we are no longer there.

- The fear of pain: This very central point for the overall argumentation of Epicurus is 'solved' relatively simply. There is no pain that is unbearable.

- The fear of having too little to live on: Here too, the solution is quite simple. - All things that are essential to life can be obtained easily. At the last two points, the general objection that Epicurus' ethics are one of the "better off" appears to be not entirely wrong.

Epicurus ethics refers to (a) the consequences of action, namely the ataraxia or the joy of life, and (b) “law” is understood to be contractual, not natural law or the like. In addition (c) the focus is on the happiness of individuals as individuals who are recommended to withdraw into private life. His ethics can therefore be understood as a forerunner of both utilitarianism (a) and contractualism (b) and had particular significance for the history of the doctrines of happiness and wisdom (c).

Stoa

For the Stoics , self-love and self-preservation represent the basic drive in general. The pursuit of this drive is at the beginning of every natural development process. In contrast to animals, however, with reason, humans also have a natural disposition that goes beyond this, which begins to stir in children from a certain point in time as a purposeful striving for knowledge.

With this discovery of reason there is an important concretization of the object of self-love. Life according to nature could now be understood as a life according to reason. In doing so, reason was not only viewed as the object of self-care, but also as the actual management authority that has to form and organize all other driving forces. In order to be able to adequately fulfill its functions, reason has to go through a lengthy educational process which gradually enables people to only adopt what is really according to their nature. The Stoics call this movement of insight and appropriation "oikeiosis" , which means the perfection of the most distinguished human qualities.

This process of perfecting is not only interpreted as an individual occurrence, but is placed in a cosmic context: the Stoics interpret the gradual appropriation of reason, which in the practical realm expresses itself as an increase in virtue, as a gradual adjustment to the general law of the world.

The practical results of this attitude are condensed in the pursuit of peace of mind ( ataraxia ), which should make you completely independent of all external circumstances and coincidences. From the fact that the true human self participates in a general world reason, there follows an inner connection and fundamental equality of all people. The world is seen as the common state of gods and humans. Because everyone is part of and dependent on this whole, the common benefit is preferable to that of the individual.

Christianity in antiquity and the Middle Ages

In Christianity, the justification of the ethos through divine revelation is preserved, but attempts are made to integrate the approaches of ancient philosophy into theology. Following Neoplatonism , assimilation to God is seen as the goal of all human activity, which, because of his sinfulness, man is able to achieve not only through his rational nature, but only through divine grace . This must be accepted by the human will - if it is still considered free at all.

The goal of human life is no longer a life in the polis, but the kingdom of God on the other side, which is differentiated from both the state and the church. The importance of the earthly is increasingly relativized and the ethical ideal is seen in a life of asceticism .

After the rediscovery of Aristotle in the High Middle Ages, the Christian ethics of virtue was further developed. The influence of his political writings also provides the basis for a rethinking of the relationship between state and church power and their gradual division.

From the Renaissance to the Enlightenment

The denominational fragmentation of the churches as a result of the Reformation led to the dissolution of a unified Christian ethos and a new understanding of state power. Its purpose is no longer the adjustment to a kingdom of God beyond, but its own self-preservation and that of its members. It is seen as the result of a contract entered into in the natural state by individual individuals.

Contract theories

As a contract theories is called conceptions that the moral principles of human action and the legitimacy of political rule conditions closed in a hypothetical, between free and equal individuals, contract see. The general ability to consent is thus declared to be a fundamental normative validity criterion.

The background of the contract theories is the conviction, which has been widespread since modern times, that moral action can no longer be justified by recourse to the will of God or an objective natural order of values. As in the Aristotelian tradition, society is no longer understood as a consequence of the social nature of man (" zoon politikon "). The only ethical subject in this conception is the autonomous, self-reliant individual who no longer stands in any given order of nature or creation. Social and political institutions can only be justified if they serve the interests, rights and happiness of individuals.

Thomas Hobbes: State of nature and legitimation of rule

Contract motifs can already be found in the thinking of the sophists and in Epicureanism; It was only in modern times, however, that the treaty was elevated to the rank of a theoretical concept of legitimation. Thomas Hobbes is considered to be the founder of contract theory . The concepts he developed shaped the entire socio-philosophical thinking of the modern age. They represent the ethical basis of liberalism .

Hobbes' starting point is the idea of a fictional state of nature . He thinks of it as a condition in which all state regulatory and security services are missing. In such a situation everyone - according to Hobbes - would pursue his interests with all means that he deems suitable and available. This pre-state-anarchic state would ultimately be unbearable for the individuals because of its prone to conflict. The cause of the conflicts was represented by the endless desires of the people and the scarcity of goods. According to Hobbes, they would lead to a situation in which everyone becomes a competitor of the other and poses a mortal danger (" Homo homini lupus "); the consequence would be the war of all against all (" Bellum omnium contra omnes "). This condition, in which there is no right, no law and no property, would ultimately be unbearable for everyone. It is therefore in the fundamental interest of everyone to leave this lawless pre-state state, to give up absolute independence and to establish an order endowed with political power that guarantees peaceful coexistence. The individual restriction of freedom necessary to establish the state of the state is, however, only possible on the basis of a contract in which the inhabitants of the state of nature mutually commit themselves to give up natural freedom and to political obedience and at the same time ensure the establishment of a contractual guarantee power endowed with a monopoly of force. The contract cannot be terminated at Hobbes, except with the approval of the sovereign. The latter has unrestricted state authority (Hobbes therefore also calls him “ Leviathan ”), as this is the only way he is able to guarantee peace, order and legal security.

Kant and the 19th century

The ethics of the 19th century was strongly shaped by the natural law and affect theory of the Stoa . This also forms the background of the Kantian ethics of duty , which shifts the moral principle into the interior of the subject and detaches it from all sensuality. There is a “division of ethics or moral doctrine into a doctrine of virtues related to morality and a doctrine of law related to legality”. The Kantian dualism of practical reason and sensuality, being and ought, forms the starting point for German idealism . The absolute is now regarded as absolute reason in which the inner subjectivity of morality and the outer objectivity of morality are abolished. In this way, "the connection between ethics, economics and politics that existed in classical antiquity is regained on the basis of the modern principle of autonomy". This principle can be seen realized in the modern state, which is viewed as the earthly realization of the absolute.

This approach, based on the autonomy of the rational subject and the consideration of the state as a moral institution, has been exposed to various attacks in the modern era up to the present day.

- of utilitarian positions that is autonomy of the subject in question and, instead, the "greatest happiness of the greatest number" accepted as the supreme value

- of socialism questions the ethical legitimacy of the state as the guardian of the common good and considers it instead as representative of the "ruling class"

- by Kierkegaard and Existentialism is importance of the state denied for the manifestation of the moral and instead the decision and choice of life of the individual in the foreground provided

- of irrational and decisionistic positions, the possibility is generally denied ever using the tools of reason to arrive at a justification of ethical norms and values.

Kant

Kant's ethics is generally regarded as the first developed conception of a deontological ethics . The deontological turn he made is primarily motivated by his endeavor to overcome the fundamental crisis in the field of moral philosophy that resulted from Hume's criticism of the naturalistic fallacy . Kant shares Hume's view that pre-moral value judgments cannot be used to derive an ought- to-be claim and that a teleological moral justification is therefore not possible.

- Formal ethics

For Kant, the moral claim does not come from experience. Its unconditional commitment can only be determined a priori , i.e. free of experience, and therefore purely formally, not materially. Kant calls this absolutely binding moral law the categorical imperative . Kant knows different formulations of the categorical imperative. The "basic formula" is in its most detailed formulation:

- "Act only according to the maxim by which you can at the same time want it to become a general law."

For Kant, the categorical imperative is the “basic law of pure practical reason”. It represents the general form of a moral law. In the "Foundation for the Metaphysics of Morals" Kant formulates the categorical imperative in the so-called "Natural Law Formula":

- "Act as if the maxim of your action should become the general law of nature through your will."

Based on this formulation, Kant uses various examples to show violations of this principle. The decisive question is whether the maxim on which the action is based can be thought of in a generalized way. If someone has to admit that there is an objectively generally applicable law, but wants to make an exception to it, it is immoral action. In order to test the morality of an action, it must be possible to imagine a natural law (an instinct that acts according to natural law) without contradiction, which a living being would always allow to proceed in this way.

- A violation of such a required ability to generalize is for Kant z. B. suicide . If I want to take my life out of self-love in the case of life weariness, then I should be able to think of a natural instinct that leads to suicide for the purpose of a more pleasant life whenever life causes too many evils to be feared. But - according to Kant - it would be obviously contradictory if the natural drive to increase the quality of life led to the destruction of life. A well-considered suicide out of boredom can therefore only be reconstructed as an ad hoc decision to be made as an exception, but not as a rule-based action and is therefore immoral.

Kant's ethics, however, do not remain purely formal, they also become material. In the so-called "end in itself formula" of the categorical imperative, the human being is placed in the foreground as an end in himself:

- "Act in such a way that you use humanity, both in your person and in the person of everyone else, at all times as an end, never just as a means."

- Autonomous ethics

Kant advocates an autonomous , not heteronomous ethic. With Kant, autonomy is to be understood in a double sense:

- as independence both from empirically material conditions or motives for action and from the arbitrariness of external legislation, because mere heteronomy cannot justify moral obligation, but must presuppose it

- as the self-legislation of pure practical reason, which can be morally bound by itself and by itself.

For Kant, however, this autonomy means nothing less than lawless arbitrariness and arbitrariness. He only wants to show that nothing empirical, neither personal experience nor external legislation, can constitute unconditional liability as such, if this does not arise as a transcendental condition of every concrete, factually empirical ought of pure practical, self-binding reason.

- Duty ethics

Kant's ethics are based on the idea of duty . For him it is the highest moral concept in which the unconditionality of the moral is expressed. Since any heteronomy is excluded, the origin of duty can only lie in the dignity of the person as a person.

Kant makes a sharp distinction between legality and morality. True morality is only achieved when the law is fulfilled for its own sake alone, when actions are only “out of duty and respect for the law, not out of love and affection for what the actions are supposed to produce”.

- Postulates of Practical Reason

Kant distinguishes between the motive (motive) and the object (object) of moral action. The only determining motive for an act that is not only legal but also truly moral can only be the law as such. For him the object is that which cannot determine the moral act, but is effected by it, that is, not the motive but the effect of moral action. For Kant - and thus it stands in the classical tradition - this object is the “highest good” ( summum bonum ). This necessarily includes two elements: “holiness” - understood by Kant as moral perfection - and bliss . Starting from this, Kant opens up the postulates of freedom , immortality and God .

- freedom

The law addresses the will, and therefore presupposes the ability of free self-determination for moral action, ie freedom of will. For Kant, freedom is not given directly, and certainly not psychologically, through inner perception, can be experienced: then it would be an empirical, that is, a content that appears sensually. Only the moral law is given directly as a “fact of pure practical reason”. The condition for the possibility of its realization is freedom of will. Kant thinks it strictly transcendental : as a condition for the possibility of moral action. As such it stands in a necessary connection with the law and can therefore be shown as a postulate of pure reason.

- immortality

The moral law commands the realization of "holiness". But “no rational being of the sense world is capable of this at any point in time of its existence” . It can therefore only be achieved in an “ infinite progressus ”, which “is only possible under the precondition of an infinitely continuous existence and personality of the same rational being (which is called the immortality of the soul)” . For Kant, the postulate of practical reason is the immortality of the soul, which he understands as an infinite process of approximate realization of moral perfection.

- God

Moral action demands, not as a motive but only as an effect, the attainment of happiness. With this, Kant takes up the basic idea of “eudaimonia”, which has been the goal of moral action since ancient Greece, with the only difference that, according to Kant, it must never be a motive, but always an object of moral action. For Kant, "bliss" means the correspondence between natural occurrences and our moral will. We could not bring about this ourselves because we are not the originators of the world and natural events. Hence a supreme cause is required which is superior to us and nature, is itself determined by moral volition and has the power to bring about harmony between natural occurrences and moral volitions. Happiness therefore presupposes the existence of God as a postulate of practical reason. For Kant, God is the ultimate reason for the absolutely valid meaningfulness of all moral striving and action.

utilitarianism

The Utilitarianism is the most elaborate and - among other reasons - for about a hundred years most talked about international variant of a consequentialist ethics . Its attraction is based on its approach, alternative courses of action can be quantified and decided through a mathematical calculation.

- Consequentialism

In utilitarianism, the moral judgment of human action is based on the judgment of the (probable) consequences of action. The consequences of the action are compared with the costs associated with the action itself.

Not every action with good consequences is therefore morally necessary. Circumstances may arise (e.g. political tyranny) in which the only possible action with good consequences requires so much moral heroism that it cannot seriously be expected of anyone.

On the other hand, not every act with bad consequences is morally prohibited under all circumstances. In some situations even an action with bad consequences may be permitted or even required, e.g. B. if the alternative courses of action - including inaction - had even worse consequences. The "consequences" include:

- the intended consequences of the act

- the unintended foreseeable consequences ("side effects") of the action

- the action and its circumstances themselves (e.g. the physical and psychological effort associated with it)

All three components must be taken into account when choosing the right action.

The decisive factor here is not the actual but the foreseeable consequences of an action, i.e. H. the consequences as they appear to a well-informed and sensible observer to be more or less likely at the time of the action. For the assessment of the action, in addition to the value and lack of value of the possible consequences, the probability of occurrence is also important. Small risks should generally be accepted for realizing great opportunities. For one-off or occasional actions with serious negative but very unlikely consequences (as with high-risk technologies), utilitarian ethics does not provide a clear decision criterion.

- Maximization principle

Among the alternatives available in each case, that action is morally required for utilitarianism which foreseeably causes the maximum preponderance of the positive over the negative consequences. This maximum is determined purely summatively. What is required is the action for which the difference between the sum of the foreseeable positive benefit and the sum of the foreseeable negative benefit is greater than for all other possible actions in the situation.

- Universalism

For the assessment of an action, the consequences for all those affected by the action are significant, whereby the evaluation of the consequences should be impartial and disregard any special sympathies and loyalties (Bentham: “Everyone to count for one and nobody for more than one” ). The consequences for the actor and those close to him are counted as part of the overall consequences, but are not given greater weight than the consequences for strangers. Spatial, temporal and social distance of those affected do not (apart from the increased uncertainty of the impact assessment) lead to a reduction in their moral relevance.

- Use as the only value

Utilitarianism has only a single value: the "benefit" ( utility ). This is usually understood as the extent of the pleasure caused by an action and the suffering avoided by it. Utilitarianism is therefore essentially a hedonistic theory. In utilitarianism, the bearer of the benefit is always the individual. "Overall benefit" or "common good" are understood as the sum of the respective individual benefits. With this approach, all value conflicts and the need to weigh up interests are eliminated at the theoretical level. Rather, only homogeneous use quantities (positive and negative) need to be offset against each other.

When determining the benefits more precisely, a distinction must be made between two different approaches within utilitarianism. Basically, the benefit is to be equated with the generation of pleasure. For classical utilitarianism ( Bentham ), all kinds of pleasure are equivalent. The alternative courses of action can therefore only be decided on the basis of quantitative aspects such as duration and intensity of pleasure. For preference utilitarianism ( Mill , Singer ), on the other hand, there are also qualitative differences in pleasure. The joys in which man's higher activities are engaged deserve preference over others; because

- It is better to be a dissatisfied person than a satisfied pig; it is better to be a dissatisfied Socrates than a satisfied fool .

The 20th century and the present

Ethics of values

The concept of value ethics is a collective term for ethical theories that understand good as value . The book Der Formalismus in der Ethik und die Materiale Wertethik by Max Scheler, however, the founder of the material ethics of values is Franz Brentano with his two main ethical works, “Vom Ursprung Morittlicher Wissen” and “Basis and Structure of Ethics” ". Both writings were decisive for Edmund Husserl's phenomenological method and also influenced Nicolai Hartmann's ethics of values . The two co-founders of early analytical philosophy, Bertrand Russell and George Edward Moore, were also influenced by the works of Franz Brentano in their ethical writings. In addition to the material ethics of values, there is also a formal direction of ethics of philosophy of value. This was developed by Wilhelm Windelband and Heinrich Rickert . Franz Brentano's ethics, despite their clear differences to Kant's ethics (but also like Kant's ethics), combine both formal principles of practical knowledge and material preferences or values of interest. In addition, it ties in with the older Thomistic tradition of the rational ethics of wisdom in some respects. Brentano's ethics of values also influenced some economic value theorists of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Material ethics of values (Scheler)

Scheler drafts his material ethics of values in an emphatic demarcation from Kant. Although he adopts Kant's a priori procedure and his criticism of an ethics of goods and purposes, he wants to adhere to a material foundation of ethics. This is possible through the demonstration of a priori value determinations that are not given in intellectual, but in emotional acts of feeling for value. For him, values are independent of concrete goods in a similar way as colors are independent of things. As a method for recognizing values, Scheler adopts the phenomenology developed by Husserl.

According to Scheler, the goal of material ethics of values is to arrive at a “doctrine of moral values that is independent of all positive psychological and historical experience”. He regards the values as “strictly a priori essential ideas”. They cannot be obtained by means of a conceptual reconstruction, but have to be extracted from the “natural worldview”. By fading out or bracketing ( epoch ) the special circumstances, the phenomenological view of the pure essence of the examined object should be made possible. This show succeeds in that it disregards the special conditions of the historically and culturally shaped situation by concentrating purely on the “act-intention detached from the person, the ego and the world context”. Scheler's material ethics of values is based on a hierarchy of values. This can be recorded "in a special file of value recognition". A value is higher, the less it is "founded" by other values and the more profound the satisfaction conveyed by its realization is experienced. Every positive value is countered by a negative “unvalue”. Scheler develops a hierarchy of values which, in his opinion, reveal themselves to a corresponding "feeling":

- the pleasant and the unpleasant (sensual feeling)

- the noble and the mean (vital feeling)

- the beautiful and the ugly; the right and the wrong (spiritual feeling)

- the sacred and the unholy (feeling of love)

Rawls

John Rawls' main work “ A Theory of Justice ” is one of the most discussed ethical works of the present. It continues the line of contract theories and turns against utilitarianism, which also dominates contemporary discussion.

Rawls understands justice primarily as social justice. He defines this as “the way in which the most important social institutions distribute fundamental rights and obligations and the fruits of social cooperation”. He criticizes utilitarianism for seeing justice in the sense of the "greatest happiness of the greatest number" only as a function of social well-being. This would not do justice to the individual rights of freedom. Every individual must be assigned “an inviolability based on justice - or, as some say, natural law”, which “cannot be undone in the name of the good of all others. It is inconsistent with justice that the loss of freedom of some could be made up for by a greater good for all ”.

- The original state and the "veil of ignorance"

In search of the legitimate principles of justice, Rawls - like the contract theorists before him - designs the thought experiment of the original state. There should be fair conditions in it that do not disadvantage or favor anyone. Every individual was in the process with a " veil of ignorance " ( veil of ignorance surrounding). In this state knows

- “Nobody has his place in society, his class or his status; just as little his natural gifts, his intelligence, physical strength, etc. Furthermore, nobody knows his idea of the good, the details of his sensible life plan, not even the peculiarities of his psyche such as his attitude to risk or his tendency towards optimism or pessimism. In addition, I also assume that the parties are not aware of the special circumstances in their own society; H. their economic and political situation, the level of development of their civilization and culture. The people in their original state also do not know which generation they belong to ” .

It is this total ignorance of one's own abilities and interests that guarantees Rawls that people “judge the principles of justice from which to choose, solely from a general point of view”.

- The two principles of justice

Under the conditions of the original state assumed by Rawls as a thought experiment, people would now agree on two principles of justice:

"1. Everyone should have the same right to the most extensive system of the same basic freedoms, which is compatible with the same system for all others.

2. Social and economic inequalities are to be designed in such a way that (a) it can reasonably be expected that they serve everyone's advantage and (b) they are associated with positions and offices that are open to everyone. "

The first principle of justice relates to the "fundamental freedoms", which Rawls includes political and individual freedoms. These are to be distributed equally for everyone. The situation is different with the economic and social goods addressed in the second basic principle. An unequal distribution can be justified here if it is of general interest. In the event of a conflict between the two principles of justice, the protection of freedom has priority. A violation of the fundamental freedoms cannot be accepted even if it could result in "greater social or economic advantages".

- Principle of difference and democratic equality

The socio-economic inequality permitted in the second principle of justice is, according to Rawls, only permissible if it helps improve the prospects of the least favored members of society. So z. B. to justify the inequality between the entrepreneurial and working class only "if its reduction would put the working class even worse". Rawls describes the order characterized by the principle of difference as the "system of democratic equality". This should be set against the "social and natural coincidences" so that "undeserved inequalities are balanced out".

Discourse ethics

The discourse ethics is currently the most prominent representative of a speech ethics. With regard to its transcendental methodology, it stands in the tradition of Kant, but extends his approach to include the knowledge of the philosophy of language - above all of the theory of speech acts . The discourse , as the exchange of arguments in a language community, is in the foreground in two respects.

On the one hand, it is seen as a means of establishing general ethics. Discourse ethics wants to show that every person who takes part in a discourse and, for example, makes, denies or questions assertions has always implicitly recognized certain moral principles as binding.

On the other hand, the discourse is seen as a means to settle concrete ethical disputes. A concrete course of action is morally correct if all of you - especially those affected by this course of action - can agree as participants in an informally conducted argumentative discourse.

Within discourse ethics, a distinction is made between a transcendentally pragmatic variant that strives for an ultimate justification of its principles ( Karl-Otto Apel , Wolfgang Kuhlmann ) and a universal pragmatic variant ( Jürgen Habermas ) that admits a fundamental fallibility of its theory.

The transcendental pragmatic approach

- The a priori of the argument

The central concern of the transcendentally pragmatic justification of ethics, whose primary representative is Karl-Otto Apel, is the ultimate justification of the underlying ethical principles. To this end, Apel strives for a “transformation of the Kantian position” in the direction of a “transcendental theory of intersubjectivity ”. From this transformation he hopes for a unified philosophical theory that can bridge the contradiction between theoretical and practical philosophy.

In Apel's view, anyone who argues always assumes that he can come to true results in the discourse, that is, truth is fundamentally possible. The person making the argument presupposes the same capacity for truth from his interlocutor with whom he enters the discourse. In Apels' language, this means that the argumentation situation cannot be evaded by anyone who argues. Any attempt to escape it is ultimately inconsistent. In this context, Apel speaks of an "a priori of argumentation":

- Anyone who takes part in philosophical argumentation at all has already implicitly recognized the presuppositions just indicated as a priori of the argumentation, and he cannot deny them without at the same time disputing the argumentative competence.

According to Apels, even those who break off the argument want to express something:

- Even those who, in the name of existential doubt that can verify themselves through suicide ... declare the a priori of the community of mutual understanding to be an illusion, confirms it at the same time by still arguing.

Someone who wants to forego an argumentative justification of his action ultimately destroys himself. In theological terms one could therefore say that even “the devil can only be made independent of God through the act of self-destruction”.

- Real and ideal communication community

In Apels' view, the inevitability of rational argumentation also recognizes a community of argumentators. The justification of a statement is namely not possible “without assuming in principle a community of thinkers who are capable of understanding and building consensus. Even the de facto lonely thinker can only explain and check his arguments insofar as he is able to internalize the dialogue of a potential argument community in the critical 'conversation of the soul with itself' (Plato) ”. This presupposes, however, the observance of the moral norm that all members of the argumentation community recognize each other as equal discussion partners.

This community of arguments, which must be assumed, now comes into play in two forms at Apel:

- as a real communication community, of which you “have become a member yourself through a socialization process”.

- as an ideal communication community "which in principle would be able to adequately understand the meaning of its arguments and to definitely judge their truth".

Apel derives two regulative principles of ethics from the necessary communication community in its two variants:

- Firstly, everything must be about ensuring the survival of the human species as the real communication community, and secondly about realizing the ideal communication community in the real one. The first goal is the necessary condition of the second goal; and the second goal gives the first its meaning - the meaning which is already anticipated with every argument.

According to Apel, both the ideal and the real communication community must be demanded a priori. For Apel, the ideal and real communication community are in a dialectical context. The possibility of overcoming their contradiction must be assumed a priori; The ideal communication community, as the goal to be worked towards, is already present in the real communication community as its possibility.

Categorization of the ethical positions

The multitude of ethical positions taken in the course of the history of philosophy is usually divided into deontological and teleological directions, although the respective classification is often controversial. The distinction goes back to CD Broad and was made famous by William K. Frankena .

| Ethical direction | Principle of action | Action objective |

|---|---|---|

| Aristotle | Development of his "telos" | the good |

| Epicurus | - | natural pleasure |

| Stoa | - | Living in harmony with nature |

| utilitarianism | - | the greatest happiness of the greatest number |

| Ethics of values | - | the values of the objects that can be recognized by phenomenological vision |

| Kant | Ability to generalize the maxim | "Holiness" and Bliss |

| Discourse ethics | Justifiability of his maxim for action in the discourse | Transformation of the real communication community into an ideal one |

| Contract theories | Agreement in a (virtual) social contract | Overcoming the state of nature |

| Rawls | Original state; Veil of ignorance | civil liberties; democratic equality |

literature

Philosophy Bibliography : Ethics - Additional references on the topic

Primary literature

- Classical works

- Plato : Politeia .

- Aristotle : Nicomachean Ethics .

- Epicurus : letters, sayings, work fragments.

- Seneca : Philosophical Writings.

- Thomas Hobbes : Leviathan .

- John Locke : Two Treatises on Government.

- -: Letter about tolerance .

- Benedictus de Spinoza : Ethics represented in the geometric order.

- Adam Smith : Theory of Ethical Feelings .

- René Descartes : On the passions of the soul.

- David Hume : A Treatise on Human Nature - Books II and III - On Affects - On Morals. (Translated by Theodor Lipps ) Felix Meiner Verlag, Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-7873-0460-6 .

- -: An examination of the fundamentals of morality. (An Inquiry concerning the Principles of Morals.) Ed. Karl Hepfer. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2002, ISBN 978-3-525-30601-7 .

- Immanuel Kant : Foundation for the Metaphysics of Morals .

- -: Critique of Practical Reason .

- Jeremy Bentham : Principles of Legislation.

- Georg W. Hegel : Basic lines of the philosophy of law.

- Arthur Schopenhauer : The two basic problems of ethics. - II. Prize writing on the basis of morality.

- Friedrich Nietzsche : Beyond Good and Evil .

- -: On the genealogy of morals .

- John Stuart Mill : About Freedom.

- -: Utilitarianism

- Franz Brentano : From the origin of moral knowledge and the foundation and structure of ethics

- George Edward Moore : Principia Ethica.

- Max Scheler : The formalism in ethics and the material ethics of values . 4th edition. Bern 1954.

- Ludwig Wittgenstein : Lecture on ethics . Suhrkamp TB Wissenschaft ISBN 3-518-28370-7 .

- Nicolai Hartmann : Ethics.

- Influential recent treatises

- Karl-Otto Apel : Discourse and Responsibility. 3. Edition. Suhrkamp 1990, ISBN 978-3-518-28493-3 .

- Jürgen Habermas : Moral awareness and communicative action. Frankfurt a. M. 1983, ISBN 3-518-28022-8 .

- Norbert Hoerster : Ethics and Interest. Reclam, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-15-018278-6 .

- Hans Jonas : The principle of responsibility . Attempting ethics for technological civilization. Nachdr. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 2003, ISBN 3-518-37585-7 .

- Alasdair MacIntyre : The Loss of Virtue. On the moral crisis of the present. Suhrkamp, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-518-28793-1 .

- John Leslie Mackie : Ethics. The invention of the morally right and wrong. Reclam, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-15-007680-3 .

- John Rawls : A Theory of Justice . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 2003, ISBN 3-518-06737-0 .

- Marcus George Singer : Generalization in Ethics. On the logic of moral reasoning. Frankfurt a. M. 1984, ISBN 3-518-07481-4 .

- Ernst Tugendhat : Lectures on Ethics. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 2003, ISBN 3-518-06746-X .

- Bernard Williams : Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Rotbuch-Verlag, Hamburg 1999, ISBN 3-434-53036-3 .

Secondary literature

- Michael Hauskeller: History of Ethics. 2 vol. Dtv, Munich 1997ff., ISBN 3-423-30727-7

- Alasdair MacIntyre : A Short History of Ethics. A History of Moral Philosophy from the Homeric Age to the Twentieth Century . London: Routledge 1967. ISBN 0-415-04027-2

- Jan Rohls: History of Ethics. 2nd edition Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-16-146706-X (standard work on the history of ethics; works out the main lines of development in the history of ethics)

Web links

- Entry in Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Plato, Laches 192b9-d12.

- ↑ Plato, Politeia 505a-b.

- ↑ Plato, Politeia 505b-d.

- ↑ Plato, Politeia 507b-509b.

- ↑ Hobbes: Leviathan

- ↑ a b Rohls: History of Ethics , p. 6

- ^ Kant: GMS , B 52

- ^ Kant: GMS , B 52

- ↑ Kant: GMS , B 66f.

- ^ Kant: KpV , A 145

- ^ Kant: KpV , A220

- ↑ Mill, Der Utilitarismus , p. 18

- ↑ Scheler: The formalism in ethics and the material ethics of values

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 23

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 46

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 160

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 159

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 81

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 82

- ↑ Rawls: A theory of justice , pp. 98f.

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 95

- ↑ Rawls: A Theory of Justice , p. 121

- ↑ Apel: Transformation of Philosophy , Vol. 1, p. 62

- ↑ Apel: Transformation of Philosophy , Vol. 1, p. 62

- ↑ Apel: Transformation of Philosophy , Vol. 2, p. 414

- ↑ Apel: Transformation of Philosophy , Vol. 2, p. 399

- ↑ Apel: Transformation of Philosophy , Vol. 2, p. 429

- ↑ Apel: Transformation of Philosophy , Vol. 2, p. 429

- ↑ Apel: Transformation of Philosophy , Vol. 2, p. 431

- ↑ CD Broad: Five Types of Ethical Theory. London 1930

- ^ William K. Frankena: Ethics. 2nd ed., Englewood Cliffs 1973; German analytical ethics. An introduction. 5th edition. dtv, Munich 1994

- ↑ archive.org: full text