History of the Jews on Norderney

The history of the Jews on Norderney has been researched for a period of around 120 years. It begins with the recording of Jewish holidaymakers in the seaside resort of Norderney from around 1820 and ends with the dissolution of the branch community during National Socialism around 1941. While bathing anti-Semitism settled on the North Sea coast towards the end of the 19th century , Norderney alone had one liberal reputation. Jewish bathers therefore preferred this East Frisian island , so that Norderney was known beyond the borders of Germany as a so-called Jewish bath until 1933 .

History of the Jews on Norderney

18th century to 1919

Norderney became the first German North Sea spa in 1797 . Jewish bathers have also been found on the island since 1820. Norderney, however, did not have its own synagogue community: the Jews living here were members of the synagogue community in Norden . Even before the First World War , Norderney was considered to be a rich Jewish spa , while Borkum and other islands were anti-Semitic , which manifested itself in the Borkumlied around 1900 . There it says:

“ Borkum, the North Sea's most beautiful ornament,

stay clear of Jews,

leave Rosenthal and Levinsohn

alone in Norderney. "

The Wangerooger Judenlied hits the same line . This ends with the refrain:

" And our cry resounds in thousand voices:

The Jew 'must' go out, he must go to Norderney "

The “other” North Sea baths were only later declared as such and therefore tried to stand out from Norderney through their anti-Semitism (initially as a unique selling point , so to speak , which later had to become more and more apparent as the other islands followed suit).

Due to the liberal reputation of Norderney, the island became more and more a popular seaside resort for Jewish vacationers, among them prominent guests such as Heinrich Heine , Franz Kafka , Felix Nussbaum and Sergei Michailowitsch Eisenstein . Anti-Semitic statements were rare here. Because of the large number of Jewish bathers, in contrast to the rest of East Frisia , more Jews settled on the island in order to offer the bathers a Jewish infrastructure. In 1840, for example, the confectioner David Bentix was given permission to run a kosher cookshop during the season , and a little later there was also a butcher who provided a room in his house as a prayer room. Since Norderney had become a nationally known upper-class seaside resort and the high nobility were among its guests during the season, it attracted bathers from wealthy, middle-class circles. Jewish entrepreneurs were strongly represented in these classes, so that many “nouveau riche” bathers stayed on Norderney.

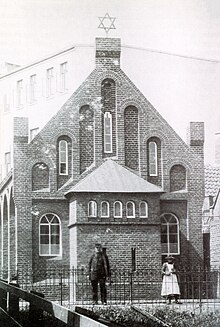

From 1877 onwards there were efforts to build a synagogue for the Jews living on the island and the visiting guests . However, this was rejected by the responsible finance department in Hanover, because they refused to provide a plot of land free of charge. In order to be able to build a synagogue on the island, an association was founded. In a letter from the governor in Norden to the Königliche Landdrostei in Aurich on October 17, 1877, it says: “In 1877 a committee was founded to promote the building of a Jewish temple on Norderney, headed by a merchant M. Bargebuhr from Harburg and a Dr. phil. Rosin in Breslau says that a private property was acquired through purchase, on which the building is to be carried out ” . The last hurdle for the approval was cleared with the declaration that the construction of the synagogue was not planned at the same time as an independent synagogue community and that the maintenance of the synagogue was secured by the association. The synagogue was finally built in 1878, based on a special decree from Emperor Wilhelm I. The building was designed by the renowned Hanoverian architect Edwin Oppler . The new synagogue was only open in the summer months; the private prayer house was still used in winter. Until 1933 this synagogue served as a prayer room for Jewish bathers.

The extent to which the Jewish bathers were present on the island's streets is made clear in a letter hostile to Jews from Theodor Fontane , which he sent home from the “ Jewish island ” of Norderney in 1881: “The Jews were fatal; their cheeky, ugly rascal faces (because their full size lies in rogue) force themselves on one everywhere. Anyone who has cheated on people in Rawicz or Meseritz for a year or, if not cheated, has done disgusting business has no right to be around in Norderney among princesses and countesses. "

The Jewish bathers were of great importance to Norderney. In 1896 there was a message in Im deutscher Reich , the newspaper of the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith: “The further upswing of our wonderful North Sea resort will be greatly helped by the fact that the North Sea resort of Amrum has recently been celebrating itself as a 'German national' in anti-Semitic papers leaves". In 1901, CW Posen wrote in the same newspaper: “Go back to Norderney, which is by no means expensive compared to other North Sea baths, if you discount the high level of comfort. The allegedly cheaper ' Jew-free ' North Sea baths cannot stand the comparison '”.

Weimar Republic

In the Weimar Republic , bath anti-Semitism reached its peak. Jews were no longer welcome on the other East Frisian islands, which meant that the proportion of Jewish bathers on Norderney rose to 50 percent in the twenties. In July 1924, however, several Jewish citizens of the island of Norderney mentioned to the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith that anti-Semitism was also beginning to spread on this island. However, they asked for the matter to be discussed as small as possible so as not to stir up further resentment. Thereupon Alfred Wiener from the Central Association asked the leader of the local Stahlhelm Association how the local association stood on the decision of the federal association not to accept Jews in the Stahlhelm. The Stahlhelm leader Schlichthorst asserted that he was not an anti-Semite and turned the accusation against the victims: It was the Jews themselves who disrupted the peace through unnecessary polemics and cultivated the anti-Semitism that was previously unknown in Norderney. Nevertheless, Jewish bathers were welcome on the island until 1933, and the coexistence of Jews and non-Jews was considered problem-free.

1933 to 1941

After 1933 the situation for Jews also deteriorated on the island. The court trainee Bruno Müller was appointed as the new mayor of the island at the beginning of July 1933 on the instructions of the Gauleiter Weser-Ems Carl Röver . Müller was born in Strasbourg in 1905 as the son of a railway clerk and had graduated from high school in Oldenburg after his family had to leave Alsace in 1919 because of their German descent. At the age of 26, Bruno Müller joined the NSDAP in 1931 . After studying law and obtaining a doctorate as a Dr. jur. In 1933/34 he became mayor of the North Sea island of Norderney, “to regulate the situation there”, as he later wrote in his résumé. As the mayor and acting head of the bathing administration, he had the necessary resources in hand.

Following his supervision, the island administration made considerable efforts to rid the island of the stain of the Jewish bath . The newspaper of the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith reported (for example) on December 14, 1933 that the spa administration on the North Sea island of Norderney had postage stamps printed with the inscription: “Nordseebad Norderney is free of Jews!”. At the same time, the spa administration had sent letters to Jewish newspapers in which, among other things, a. meant “that Jewish spa guests are not welcome on Norderney. Should Jews nevertheless try to find accommodation in Norderney in the coming summer, they have to bear the responsibility themselves. In the event of friction, the bathing administration would have to expel the Jews from the island immediately in the interest of the bath and the German spa guests present. "

In August 1933, the Norderneyer bath newspaper reported on a Jewish spa guest who was denounced by other spa guests for desecration because he shared two continuous rooms with a Christian girl. The police and SA attacked the man at night and took him into protective custody two years before the Nuremberg Race Laws were passed . The Norderneyer Bäderzeitung called for a concentration camp and a death penalty for the man and went on to write: “The next Jew who would be caught here in the same way could have to go for an involuntary walk here in broad daylight, adorned with a poster on which Name, address and facts of his actions would be briefly communicated to everyone. "

From 1937 at the latest, the Jews had to live with numerous other restrictions, regulations and harassment, until they were completely banished from resorts in 1938/1939.

The synagogue, in which there has been no service since 1933, was sold on July 11, 1938 to a Norderneyer hardware dealer for 3500 Reichsmarks on the condition that all references to the synagogue be removed. The conversion to a storage room did not take place until after the November pogroms in 1938, and so the Star of David remained on the gable. The synagogue itself was spared the actions in connection with the November pogroms, but SA men are said to have tried to remove the Star of David from the gable, but they did not succeed.

On November 10, 1938, the SA rounded up the island's Jews and led them to a fenced-in place in front of what is now the island's house . They had to stand there all day. In the evening they could go home: in contrast to the other Jews of East Frisia, they were not deported because the local SA did not have the instructions to do so. However, most of the Jews left the island in the months that followed. The last remaining Jews were two women who were married to non-Jews. They too left Norderney in April 1941 at the latest.

After 1945

In April 1941 the Jewish citizens were practically eliminated. Of the former Jewish residents, only one woman returned to Norderney after 1945, in the meantime she moved to Augsburg, but spent the last years of her life on Norderney again.

For a long time, the city of Norderney found it difficult to remember the Jewish past. The erection of the monument in honor of Heinrich Heine caused controversy . The poet had visited Norderney in 1825 and in the two following years and processed his impressions literarily. A sculpture in front of the Kurtheater has been a reminder of this since 1983. It goes back to a design by the sculptor and architect Arno Breker from 1930. Breker was living in Paris at the time, but regularly responded to German tenders. With his Heine design, he won second prize in a competition organized by the city of Düsseldorf , Heine's birthplace , in 1932 . After the seizure of power by the National Socialists, who, based on their anti-Semitic denigrating ideology person and work of Heine, a list of the monument in the public space was impossible. Breker settled in Berlin at the end of 1933 and rose to become the most prominent sculptor of the Third Reich. On September 10, 1937, he applied for membership in the NSDAP .

In 1979, a Heinrich Heine Memorial Society was founded in Düsseldorf that campaigned for Breker's design to be carried out. A year later, the artist began to make an eighty-centimeter high model of a crouching youth with a book in his hand. This model was enlarged in Paris in a ratio of 1: 2 to 160 cm and cast in bronze . The culture committee of the city of Düsseldorf, however, rejected the installation of the sculpture, as did the city of Lüneburg , in which Heine had temporarily lived with his parents.

The society then decided to donate the monument to the city of Norderney in agreement with Breker. Although the city council unanimously accepted the gift, a citizens' initiative was formed: Heine ja - Breker no , which criticized the sculptor's National Socialist past. Despite violent protests by the population and accompanied by a critical statement by the PEN Center in London, the sculpture was nevertheless placed in front of the Kurtheater on December 6, 1983. The text is engraved on the east-facing side of the base:

"I LOVE THE SEA LIKE MY SOUL"

He refers to Heine's cycle Die Nordsee , which was created on Norderney.

In 1988, on the 50th anniversary of the pogrom night, a memorial plaque was placed on the island's house with the words

" In memory

of the Jewish fellow citizens of

the city of Norderney

who

had to die a violent death or were expelled from the Nazi terror.

To the living as a reminder

November 9, 1988

The City Council of Norderney "

remembered the Jewish residents of Norderney.

After 1945, the building of the former synagogue was used as a discotheque, an Argentine steak house and later as an Italian restaurant. Today it is a restaurant for regional specialties. Only the side wall on the north side of the building has remained in its original condition, otherwise the building has undergone major structural changes. It was not until 1996 that a memorial plaque was placed on the facade of the building at the suggestion of the Evangelical Youth of Norderney. This bears the inscription:

“ Former synagogue (1878–1933)

This building was built as a house of prayer for Jewish

citizens and guests.

Sold in July 1938 , it escaped destruction in the pogrom night

of November 9th of the year

In Remembrance and Commemoration. "

In the meantime, the Norderney City Archives have also designed an exhibition on the subject of Jews on Norderney , with which, for the first time, Jewish life, the contribution of Jews to the development of the North Sea resort and the measures to exclude and annihilate Judaism on Norderney are presented to a wider public.

Community development

| Jewish community members 1867–1941 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | Parishioners | |||

| 1867 | 6th | |||

| 1871 | 9 | |||

| 1885 | 31 | |||

| 1895 | 35 | |||

| 1905 | 35 | |||

| 1925 1 | 88 | |||

| 1933 | 28 | |||

| 1935 | 9 | |||

| 1939 | 3 | |||

| 1941 | 1 | |||

|

1The counting did not take place in December, as usual, but at the beginning of the bathing season.

The actual number of Jews permanently living on Norderney is likely to have been lower. |

||||

Norderney was not a separate synagogue community; the Jews living here were part of the synagogue community in Norden. Even if more and more Jews settled on Norderney due to its importance as a Jewish spa and their proportion of the population increased in contrast to the rest of East Frisia until 1925, nothing about this status changed until the end of Jewish life on Norderney.

Memorials

A memorial plaque was mounted on the building of the former synagogue at Schmiedestrasse 6 (see picture) . Another memorial plaque has been installed in the island's house since November 1988. Its inscription reads: “In memory of the Jewish fellow citizens of the city of Norderney, who either had to die a violent death or were expelled due to the National Socialist terror. As a warning to the living ”.

On February 22, 2013, Gunter Demnig laid eight stumbling blocks at four locations (Bismarckstrasse 4, Bismarckstrasse 8, Strandstrasse 10, Karlstrasse 6) in the city.

literature

- Daniel Fraenkel: North / Norderney. In: Herbert Obenaus (Ed. In collaboration with David Bankier and Daniel Fraenkel): Historical manual of the Jewish communities in Lower Saxony and Bremen . Wallstein, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-753-5 , pp. 1122-1139.

- Ingeborg Pauluhn: Jewish migrants in the seaside resort of Norderney 1893–1938 . With special consideration of the children's rest home. UOBB Zion Lodge XV. No. 360 Hanover and Jewish businesses. Igel Verlag, Hamburg 2011, ISBN 3-86815-541-4 .

- Lisa Andryszak, Christiane Bramkamp (ed.) (2016): Jewish life on Norderney. Presence, diversity and exclusion . Münster: LIT (publications of the Center for Religious Studies Münster, 13). ISBN 978-3-643-12676-4 .

- Harald Kirschninck: Nordseebad Norderney is free of Jews. The history of the Jews of Norderney from settlement to deportation. BOD-Verlag, Norderstedt 2020, ISBN 978-3-7519-3374-2 .

- Harald Kirschninck: Where did you go? Biographies and stories of the Jews of Norderney. Volume 1. AK. BOD-Verlag, Norderstedt 2020, ISBN 978-3-7519-5411-2 .

- Harald Kirschninck: Where did you go? Biographies and stories of the Jews of Norderney. Volume 2. LZ. BOD-Verlag, Norderstedt 2020, ISBN 978-3-7519-0007-2 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Jews on Norderney . Friends of the Museum Nordseeheilbad Norderney eV. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ Herbert Obenaus (Ed.), Historical Handbook of the Jewish Communities in Lower Saxony and Bremen . ISBN 3-89244-753-5 , p. 1130.

- ↑ Ingeborg Pauluhn: On the history of the Jews on Norderney. From acceptance to disintegration. with documents and historical materials . Oldenburg 2003. 240 pages. ISBN 3-89621-176-5 , p. 27

- ↑ STAA, Rep. 15 12626

- ↑ Quoted from: Wolfgang Benz : Bilder vom Juden. Studies on everyday anti-Semitism , CH Beck Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 978-3-406-47575-7

- ↑ Anonymous, In: In the German Reich , Vol. 2 (1896) No. 7, pp. 397–398.

- ↑ CW Posen, In: In the German Reich , Vol. 7 (1901) No. 5, pp. 302-303.

- ↑ a b Michael Wildt : He has to go out! He must go! - Anti-Semitism in German North and Baltic Sea baths 1920–1935 , in: Mittelweg 36 . Journal of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research , Volume 4, 2001.

- ^ The end of the Jews in East Friesland , catalog for the exhibition of the East Frisian landscape on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht, Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1988, ISBN 3-925365-41-9 .

- ^ Frank Bajohr, Our hotel is free of Jews . Baths anti-Semitism in the 19th and 20th centuries, 2nd edition Frankfurt a. M. 2003, p. 117.

- ^ The end of the Jews in Ostfriesland , catalog for the exhibition of the East Frisian landscape on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht, Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1988, p. 64

- ↑ Cf. Birgit Bressa, Nach-Leben der Antike. Classical images of the body in the Nazi sculpture Arno Brekers , Diss.Tübingen 2001, p. 19.

- ↑ Jürgen Trimborn, Arno Breker. The artist and power , Berlin 2011.

- ↑ According to another representation, the model was 90 cm high; see. Magdalene Bushart (ed.), Sculpture and Power. Figurative sculpture in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s, Berlin 1984, p. 175.

- ↑ Dagmar Matten-Gohdes: Heine is good. A Heine reading book . Beltz and Gelberg, Weinheim 1997, p. 192 .

- ↑ Ulrike Müller-Hoffstede, Heine monuments: sculpture and power. Figurative sculpture in Germany in the 30s and 40s . Ed .: Magdalene Bushart. Berlin 1984, p. 141 ff .

- ↑ Rudij Bergmann: The Loreley is in the Bronx . In: Jüdische Allgemeine . February 16, 2006.

- ^ Restaurant de Leckerbeck on Norderney - The story

- ↑ Ingeborg Pauluhn: On the history of the Jews on Norderney. From acceptance to disintegration. with documents and historical materials . Oldenburg 2003. 240 pages. ISBN 3-89621-176-5 , p. 49

- ↑ Manfred Bätje, Ottmar Heinze: Norderney . Seaside resort with tradition. Ellert & Richter Verlag GmbH, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-8319-0147-3 , Insel-Notes, p. 95 .

- ↑ Chronicle . Gunter Demnig. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

Coordinates: 53 ° 42 ' N , 7 ° 9' E