History of the Jews in East Frisia

The history of the Jews in East Friesland spans a period of approximately over 400 years since their beginnings in the 16th century. During the late Middle Ages and early modern times, East Frisia was the only area in northwest Germany where Jews were tolerated. After the dynasty of Cirksena died out in 1744 and the associated end of the county of East Frisia as a sovereign state, East Frisian Jews became citizens of Prussia , whose restrictive legislation was also applied against Jews in East Frisia. In the 19th century, sovereignty over East Frisia changed several times, which brought about changing legal framework conditions for the Jews.

By 1870 new laws finally brought civil rights for Jews in East Frisia. The last legal discrimination was removed by the end of the First World War . From the mid-1920s there was an accumulation of anti-Semitic incidents in East Frisia. During the Nazi era , the Jews were gradually disenfranchised and persecuted. Jewish life in East Frisia finally died out in 1940. About 50 percent of the Jews of the Jews recorded in the German Reich census of June 16, 1925 in East Frisia (and thus around 1000 out of 2146) were murdered by the National Socialists during the Holocaust . The few Jews living in East Friesland today are part of the Jewish community in Oldenburg .

Possible immigration in the Middle Ages

When exactly the first Jews settled in East Frisia is unknown. According to legend, the first Jews were supposed to have been settled in East Frisia by Ocko I. tom Brok . He stayed in Italy in the 1370s and was knighted by Queen Johanna I of Naples after completing military and court services . There he is said to have come into contact with Jews so that they could settle in East Frisia in order to promote the region's economic development.

In fact, connections between Frisians and Jews outside Friesland had existed since the 11th and 12th centuries at the latest. In the high Middle Ages of the 11th and 12th centuries , Jews (since 1084) and Frisians in Speyer provided the majority of long-distance merchants (negotiatores manentes), both of whom had their seats in the merchants' settlement prior to cathedral immunity.

Although this has not yet been proven, there are indications of a connection between the East Frisian Jews and Italy. For a long time , the Jewish community of Aurich used a Jewish prayer book ( Machsor ) that appeared in Venice around 1600 . The secure settlement of Jews began in the middle of the 16th century in the port cities of East Frisia. Possibly the expulsions of the Jewish communities from the Rhineland favored the settlement in East Frisia.

16th century to 1618

Jews have lived in the Weser-Ems area since the Middle Ages and the first Jews settled in Emden as early as 1530 . In the county of East Friesland, the city of Emden initially had the right to issue protection letters for Jews . Subsequently, synagogue communities were founded in all East Frisian cities and some spots , for example in Norden (1577), Jemgum (1604), Leer (1611), Aurich (1636), Esens (1637), Wittmund (1637), Neustadtgödens (1639), Weener (1645), Bunde (1670) and Dornum (1717). From 1878 there was a branch of the Synagogue Community on Norderney ( see: History of the Jews on Norderney ). During the late Middle Ages and early modern times , East Frisia was the only area in northwest Germany where Jews were tolerated. They had to leave Oldenburg as a result of the plague epidemic of 1349/50 and Wildeshausen in 1350 after they were accused of well poisoning . They were only allowed to settle there again at the end of the 17th century.

The legal framework for Jews in East Frisia was regulated by “letters of protection” or “general privileges”, which the East Frisian rulers issued for the various districts (offices) of the country. They had a term of 10, 15 or 20 years and were then extended. The Jews living in East Frisia are listed by name in the letters of protection. Such letters of protection are verifiable for the years 1635 (extension 1647), 1651, 1660, 1671, 1690, 1708 up to the general privilege of the last Cirksena Prince Carl Edzard from the year 1734. Basically, the general privileges regulated:

- Protection of the home and personality

- Securing undisturbed ritual life, religious practice and funeral burial

- The organization of the community under the rabbi with its own jurisdiction

- Trading permit with limitation of usury , the right of pledge and realization

- Moving in and out, special letters of protection for settlement, marriage and wedding money

- Assurance of escort and protection order to all authorities in the country.

The Jewish communities in East Friesland were initially directed by the court Jews , later by the state rabbinate in Emden, which was also responsible for Osnabrück . The regional rabbi was the spiritual leader. In the individual communities, elected rulers administered all matters relating to synagogues, schools and the poor. Religious life in the smaller communities was shaped by the Jewish teacher. He also worked as a prayer leader at the synagogue service and as a slaughterer provided kosher meat. The Jews in East Frisia were forbidden to work as craftsmen or farmers, which is why they mostly worked as traders or butchers. As a result, markets were unthinkable without Jewish traders, butchers and cattle dealers, even though the proportion of Jews in the East Frisian population was only 1%. Most of the Jews in East Frisia lived in simple or average circumstances.

Thirty Years' War

On the one hand, the Thirty Years' War guaranteed wealthy Jews a right to stay due to the constantly growing need for money of the warring parties, but on the other hand it burdened them to a previously unknown extent. Her list of financial commitments was long. In 1629 the Emden Jews (as representatives of the Jewish communities of East Frisia) paid 180 guilders protection money per year, 200 guilders peat money (levy for a fireplace) and about 2,000 guilders in various consumption taxes, for a total of around 2,380 guilders. In addition, there were rent, marriage fees, and extraordinary fees to the sovereign: 4 guilders protection money per household plus 150 Reichstaler entry fees. The son of a deceased member had to pay this in order to enter into the rights of the father.

When Count Ulrich II had to raise a lot of money for the withdrawal of the Hessian troops from East Friesland at the end of the Thirty Years' War , Countess Juliane pledged jewels worth 54,650 guilders through the mediation of the court Jew in Amsterdam and received larger loans in several installments.

1645 to 1744

Overall, the situation of the Jews in East Frisia was relatively good compared to other areas until 1744. The Jewish community in Emden was allowed to build its cemetery within the city walls (1700). This was an extraordinary concession, but until the 19th century Jews had to remain without civil rights and live under special laws.

The general letter of conduct issued by Count Ulrich II in 1645 allowed the Jews of East Frisia to live according to their own "Jewish order". In 1670 Princess Christine Charlotte had a general escort letter written which allowed Jews to hold services in their homes or in their own synagogues . He also stipulated that they were allowed to bury their dead according to Jewish custom. Complaints from the shopkeepers' guilds about the Jewish traders were not heard by the respective sovereigns. Georg Albrecht replied to a complaint from the year 1710: "that in East Friesland the escorted Jews and in particular the city of Aurich were at all times in the immemorial position of free trade and change."

1744 to 1806

The liberal attitude towards the Jews changed when Prussia came to power in 1744. This led to a significant deterioration in the situation of the Jews; because the restrictive Prussian legislation against Jews now also applied in East Frisia. The declared aim of the Prussian government was to reduce the proportion of Jews in East Frisia. The taxes to be paid by Jews were increased significantly, they were prohibited from owning real estate, and numerous restrictions and prohibitions were imposed on Jewish traders. At that time the Jews of East Frisia paid the annual sum of 776 thalers. Now the letter of protection could only be passed on to the eldest son; two other sons could obtain it for the comparatively high sum of 80 thalers. The other sons had to remain unmarried and therefore childless or emigrate. It was also the tariff barriers of degrading, otherwise usual only for livestock body tax payable. The desired reduction in the proportion of the Jewish population was not achieved, but many Jews became impoverished, so that as early as 1765 two thirds of the Jewish population was living in the most miserable conditions. On the other hand, there was a small upper class, which mainly consisted of large merchants and bankers. Overall, the Jewish communities of East Frisia were among the poorer in Germany.

Anti-Semitic remarks and actions were rare until the early 1930s. Only the Calvinist Church in Emden protested against the tolerance of the Jews, which, however, was not heard by the city's magistrate. In 1761 and 1762, in connection with the turmoil of the Seven Years' War , there were major riots against Jews for the first time. Several houses were looted because the population blamed Jews for the poor supply situation.

1806 to 1815

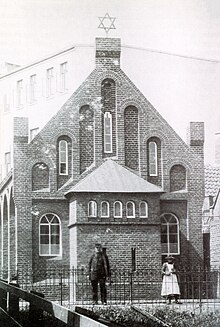

After the battle of Jena and Auerstedt , East Frisia was incorporated into the Kingdom of Holland and thus into the French sphere of influence. In 1810, the Ems-Oriental ("Osterems") department became part of the French Empire. For the Jews this meant a significant improvement in their situation. In two decrees of June 4, 1808 and January 23, 1811 they were granted civil rights and full equality. During this time, a very good relationship between the Jewish and Christian population can be assumed, which can be measured, among other things, by the willingness of the Aurichians to donate when the Jewish community planned to build its own synagogue in 1810. Even in the Dutch period, the Aurich community began building the synagogue, which was built according to plans by the architect Bernhard Meyer and consecrated on September 13, 1811. Despite these improvements, the Jews also found foreign rule oppressive and took part in the wars of liberation against Napoleon.

After the defeat of Napoléon and the collapse of his empire, East Frisia came under Prussian rule again from 1813 to 1815. As a result, the Prussian Jewish edict of March 11, 1812 came into effect in East Frisia. Jews, until then regarded as “servants of Jews” in the Prussian state, became full citizens, provided they were willing to accept permanent family names and submit to military service.

1815 to 1866

After the Congress of Vienna (1814/1815), Prussia had to cede East Frisia to the Kingdom of Hanover . Due to a lack of instructions from the new rulers, the legal situation for Jews was extremely confused. According to Article XVI of the German Federal Act of June 8, 1815, it was provided that the Federal Assembly (...) should consult, as in as coherent a manner as possible the civil improvement of the confessors of the Jewish faith in Germany must be brought about, and how, in particular, the enjoyment of civil rights against the assumption of all civic duties in the federal states can be procured and secured for them; however, until then those who believe that belief will receive the same rights granted by the individual states. The Hanoverian government relied on the last sentence of this article, but gave no clear instructions on the situation of the Jews in East Frisia. The administration in particular acted in this area initially according to Prussian law, taking into account the Jewish edict. In 1829 the Landdrostei Aurich in Hanover pleaded for a Jewish-friendly interpretation, but received instructions to the contrary. In 1819 the guilds were reintroduced, which largely excluded Jews from the craft. In contrast to the rest of the Kingdom of Hanover, the protective Jewish status was not reintroduced in East Frisia. Since 1824 the “Oberlandespolizeiliche permit” has taken its place. Without this, Jews in Emden could no longer settle down and marry. Jews were also prohibited from voting and assuming municipal offices. Permission to settle could only be transferred to an only son if the father had given up his business or died.

The administrative structures within the Jews of East Frisia were unclear at that time. For the Landdrostei was officially still Isaak Beer, who was appointed by the Prussians but retired in 1808, as the Land Rabbi. The East Frisian Jews outside Emden were without rabbis. Abraham Lewy Löwenstamm, who had already been elected Chief Rabbi of the Department by the Jewish communities in the Département de l'Ems oriental in 1813 in the French period , proposed to the Landdrostei in 1820 that he be appointed State Rabbi , since Beer no longer held his office. He didn't even get an answer. It was not until Isaak Beer died in 1826 and the Emden magistrate proposed Löwenstamm as his successor in the land rabbinate that the Emden rabbi was given the office of land rabbi, and in 1827 the Landdrostei agreed that he should take up his official residence in Emden.

Like the Prussians before, the Hanoverians tried to reduce the number of Jews in East Frisia, but had only moderate success. Only with the law on the legal relations of Jews of September 30, 1842 was a uniform legal basis created for all Jews in the Kingdom of Hanover. It allowed the Jews to choose their place of residence and to practice various professions. As a result, they still had no political rights and were still excluded from government office.

1866 to 1901

After the annexation of the Kingdom of Hanover by Prussia in 1866, East Frisia became Prussian again and the Jewish edict was applied again. By 1870 new laws finally brought civil rights for Jews in East Frisia. The last (legal) discrimination was reduced by the end of the First World War . Now the East Frisian Jews could be elected to the city council or become members of an association. For example, Jews became city councilors or members of the association “Maatschappy to't Nut van't Generaleen” (society for the benefit of the general public) and the East Frisian Chamber of Commerce. The chairman of the Jewish community in Emden, Jacob Pels, became a member of the council of citizens in 1890.

Land rabbis

After the Napoleonic annexation of northern Germany, the Consistoire Emden was set up for the Départements de l'Ems-Supérieur and Ems Oriental based on the French model . A Chief Rabbi (grand-rabbin) supervised the communities in Konsistorialbezirk. He officiated as a regional rabbi from 1827. In 1842 the Kingdom of Hanover established land rabbinates in Emden, Hanover , Hildesheim and Stade. The Land Rabbinate Emden included the Landdrosteien Aurich and Osnabrück . In 1939 the Nazi authorities lifted the land rabbinates.

- 1812–1839: Abraham Heymann Löwenstamm (1775–1839), from 1812 Grand Rabbi of the Consistoires Emden, from 1827 State Rabbi for East Frisia

- 1839–1841: vacancy

- 1841–1847: Samson Raphael Hirsch (1808–1888), land rabbi of Emden

- 1848–1850: Josef Isaacson (1811–1885), deputy land rabbi

- 1850-1852: vacancy

- 1852–1870: Hermann Hamburger (approx. 1810–1870), land rabbi of Emden

- 1871–1873: Philipp Kroner (1833–1907), city rabbi of Emden, interim as land rabbi

- 1875–1892: Peter Buchholz (1837–1892), elected in 1873, then introduced in 1875 as Land Rabbi of Emden

- 1892-1894: vacancy

- 1894–1911: Jonas Zvi Hermann Löb (1849–1911), land rabbi of Emden

- 1911: Abraham Lewinsky (1866–1941), land rabbi of Hildesheim, acting as representative

- 1911 / 13–1921: Moses Jehuda Hoffmann (1873–1958), land rabbi of Emden

- 1922–1939: Samuel Blum (1883–1951), city and country rabbi of Emden

Baths anti-Semitism

Bath anti-Semitism spread on Borkum at the end of the 19th century . During this time, numerous baths campaigned unabashedly so, " free of Jews to be" read, among others, in an island of Borkum leader for from 1897. The Borkum song was written, which was played daily by the spa orchestra and sung by the guests. Here it says in the chorus:

“At Borkum's beach only German is valid, the banner is only German. We keep the Germania badge of honor for and for! But whoever approaches you with flat feet, with crooked noses and curly hair, shouldn't enjoy your beach, he has to go out, he has to go! "

Borkum was already a stronghold of the anti-Semites at the turn of the century. There were signs on hotels that read “Jews and dogs are not allowed in here!” , And inside there was a “timetable between Borkum and Jerusalem (return cards are not issued)” . A 1910 published guide on the North Sea resorts advised "Israelites" especially from visiting Borkum from, "because they must be gewärtig else to be bothered by the sometimes very anti-Semitic visitors in rücksichtslosester way." Even were the Jews with recreation islands like the Jews island Norderney continued to have some rooms open in which they could spend their vacation largely undisturbed by discrimination.

Zionism

The Zionism first appeared in the early 20th century in Emden in appearance. In 1901 35 Jewish citizens founded the local group "Lemaan Zion" of the Zionist Association for Germany. As in the rest of the empire, this movement found favor with only a very small fraction of the Jewish population. The community leadership around Rabbi Dr. Löb and Teacher Selig were skeptical or even negative about Zionism and described the followers of Zionism in community meetings as “ journeymen without a fatherland ”.

Weimar Republic

In the 1920s, Pastor Ludwig Münchmeyer from Borkum incited the audience with anti-Semitic hate speech; other agitators from the working class or the trades met with a good response, especially in the larger towns, due to their professional and social proximity to the proletariat. From now on, anti-Semitic incidents increased. In August 1926, there were fights at the Leeran cattle market between students wearing a large swastika on their jackets and Leeran Jewish cattle dealers. Shortly before Christmas 1927, the Völkische Freiheitsbewegung distributed leaflets directed against Jewish businessmen with a clearly racist background. At the time of the global economic crisis, anti-Semitism increased, which was directed against the Jewish cattle trade, which some met with prejudice and distrust during the agricultural crisis at the time. Even on Norderney, which had previously courted wealthy Jewish guests, Jews were more tolerated than welcomed in the 1920s.

1933 to 1938

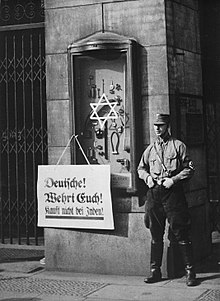

After the National Socialists came to power in 1933, the Jews in East Friesland suffered repression by state organs. Two months after the seizure of power and four days earlier than in other parts of the German Reich , the boycott of Jewish businesses began in East Frisia. On March 28, 1933, the SA posted itself in front of the shops. During the night, 26 shop windows were thrown in Emden , which the National Socialists later wanted to blame the Communists on.

On the same day, Anton Bleeker , the SA -Standartenführer in Aurich (for Oldenburg-Ostfriesland from July 1934), issued a slaughter ban for all East Frisian slaughterhouses and ordered that the slaughter knife be burned. This led to the first major incident on March 31, 1933, when the synagogue in Aurich was surrounded by armed SA men. The SA forced the surrender of the slaughter knives in order to then burn them in the marketplace. Public burnings of slaughter knives also took place in Weener and Emden. The Ostfriesische Tageszeitung (OTZ) also published inflammatory articles such as “German people's struggle against Israel's world conspiracy. Judas hour has struck ”. While there were still non-Jewish neighbors during the actual boycott days who bought secretly at the back door or after the shop had closed, this was by and large the exception. If anti-Semitism had remained an insignificant marginal phenomenon in East Friesland until 1933 (the exception was the bath anti-Semitism mentioned above on Borkum), it was now supported by the majority. The calls by the National Socialists to boycott the Jews did not fail to achieve their goal. A citizen of Aurich - Wilhelm Kranz, the founder of the NSDAP local group - photographed the citizens who were buying in Jewish shops in order to pillory them in the Kdf display cases. This worsened the economic situation of the owners of these businesses. One after the other had to be given up and was thus " Aryanized " the cold way .

The boycott was officially ended after a few days, but the discrimination continued through propaganda, ordinances and laws. At the weekly cattle market in Weener there was a “place for Jews” marked by a sign. There the Jewish cattle dealers could offer their cattle. But this place was monitored so that nobody dared to approach this corner. The situation was similar at the cattle market in Leer, the largest market of its kind. A part of it was now fenced off for Jews. In the north there were attacks by the SA against a young Jew and his “Aryan” girlfriend for so-called “ desecration ”, at which spectators applauded. A little later another young woman was picked up who had been accused of having relationships with a Jew, and she was shown around town. The sign that she had to wear around her neck read: "I am a German girl and have let myself be violated by the Jews". The Ostfriesische Tageszeitung placed several special supplements under the title: "The Jews are our misfortune". With the call "Volksgenossen, do not buy in the following Jewish shops", the newspaper listed all the shops in East Frisia that still existed in East Frisia.

Such actions triggered the first wave of Jewish emigration and refugees across the empire, which in East Friesland initially mainly affected small towns such as Dornum and Esens. Dornum lost a third of its Jewish population in 1933. The majority moved within Germany. In cities like Aurich and Emden, the emigration rate was much lower. Increased emigration from Aurich did not begin until 1937; Nevertheless, only around a quarter of the Jewish residents had emigrated by the night of the pogrom. Among the Jews who had fled in 1933 was Max Windmüller , who later joined the resistance of the Westerweel group in the Netherlands under his code name Cor and saved many Jewish children and young people. The newspaper of the " Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith " reported on December 14, 1933 that the spa administration on the North Sea island of Norderney had stamps printed with the inscription: "Nordseebad Norderney is free of Jews!" At the same time, the spa administration had sent letters to Jewish newspapers in which it said, for example, “that Jewish spa guests are not welcome on Norderney. Should Jews nevertheless try to find accommodation in Norderney in the coming summer, they have to bear the responsibility themselves. In the event of friction, the bathing administration would have to expel the Jews from the island immediately in the interest of the bath and the German spa guests present. "

In 1935, customers of Jewish shops were photographed and denounced. As a result, the economic situation of the business owners deteriorated, so that one business after the other had to be given up and in this way " Aryanized ". Anyone who continued to deal with Jews had to expect insults, disadvantages and complaints from the National Socialists. A complaint against an Oldersum dealer has survived.

The municipal bathing establishment at the Kesselschleuse in Emden denied entry to Jews in the same year because the population allegedly felt harassed. Nevertheless, only a minority of East Frisian Jews saw a way out in selling their property and emigrating. Most of the East Frisian Jews still wavered between hope and despair. Exact and reliable statistics on emigration and emigration are not possible due to the sometimes contradicting sources.

In 1937 Heinrich Drees published an article in the Ostfriesische Tageszeitung in which he tried to justify the persecution of the Sinti and Jews historically and wrote that "vagabond Jews make the province of Hanover and East Frisia unsafe". For the period from 1765 to 1803 he listed various passages by gangs of thieves in East Friesland and always assumed that their members were "Jews and Gypsies". It also said: "In the East Frisian cities, especially in Aurich, vagebound hunts were held constantly, which were also called 'Kloppjagden' in the vernacular. During these Kloppjagden a lot of stolen property was confiscated and many Jews were chased across the border."

The Jewish community in East Friesland felt compelled to make arrangements for housing the older community members. In addition to the old people's home in Schoonhovenstrasse (Emden), she built an extension to the orphanage in Klaas-Tholen-Strasse.

By the November pogrom of 1938 , around half of the Jews living in the Aurich administrative district had left their East Frisian homeland.

November pogroms 1938

On November 7, 1938, the seventeen-year-old Polish Jew Herschel Grynszpan , who was living in Paris , shot at the NSDAP Legation Secretary Ernst Eduard vom Rath in the German Embassy . He died on November 9th from his injuries. In the evening, news of Rath's death reached the old town hall in Munich, where the National Socialist leadership had gathered to commemorate the 1923 Hitler coup .

At around 10 p.m. Goebbels then gave an anti-Semitic inflammatory speech in front of the assembled SA and party leaders, in which he made “the Jews” responsible for the death of von Rath. He praised the supposedly "spontaneous" anti-Jewish actions throughout the empire, during which synagogues were also set on fire, and referred to Kurhessen and Magdeburg-Anhalt. He stated that the party should not appear publicly as an organizer of anti-Jewish actions to be carried out, but that it would not hinder them.

The Gauleiter and SA leaders present understood the meaning of this message. It was an indirect but unmistakable call for organized action against Jewish houses, shops and synagogues. After Goebbels' speech, they phoned their local offices around 10:30 p.m. Afterwards they gathered in the hotel "Rheinischer Hof" in order to give further instructions for actions from there. Goebbels himself had telegrams sent from his ministry to subordinate authorities, Gauleiter and Gestapo offices in the Reich at night after the commemoration ceremony. On this day there were two lines of command in East Friesland, which partly worked together, but partly also acted in opposition. The SA (1st line of command) wanted to appear quite openly in uniform and the NSDAP Gauleitung (2nd line of command) wanted to make the actions look like a spontaneous outbreak of popular anger, so they issued an order to carry out all actions in "robber civilian". For north-west Germany, Gauleiter Carl Röver , who was present in Munich, gave the order for the actions via the NSDAP Gauleitung at 10:30 p.m.

The more important chain of command for the actions, however, ran through the SA offices. The leader of the SA group North Sea (based in Bremen), Obergruppenführer Johann Heinrich Böhmcker , who was also present in Munich , gave the order by telephone that mobilized the local SA storms:

“All Jewish shops are to be destroyed immediately by SA men in uniform. After the destruction, an SA guard has to pull up to ensure that no valuables can be stolen. [...] The press is to be consulted. Jewish synagogues are to be set on fire immediately and Jewish symbols are to be secured. The fire brigade is not allowed to intervene. Only the houses of Aryan Germans need to be protected, but the Jews have to get out, as Aryans will move in there in the next few days. [...] The Führer wishes that the police do not intervene. All Jews are to be disarmed. If there is resistance, shoot it over the heap. At the destroyed Jewish shops, synagogues, etc., signs must be put up with the following text: 'Vengeance for murder on vom Rath. Death to international Judaism. No communication with peoples who are Jewish. ' This can also be extended to Freemasonry . "

In Emden, NS district leader Bernhard Horstmann received a call from the Gau leadership in Emden at 10:30 p.m. This then consulted with other party officials to coordinate the actions of the night.

The district leader from the north was not reached until midnight by the district chief Meyer, who happened to be in Emden. The latter informed him that the responsible SA leader in the north, Sturmbannführer Wiedekin, could not be reached. Ewerwien should take this into their own hands. After he remained inactive at first, Oldenburg asked him to wake Wiedekin at around 1 a.m. After alerting the SA, Wiedekin passed the order on to the SA in Dornum, which was subordinate to him.

Erich Drescher , Mayor of the city of Leer, was called at home by the Oldenburg Gauleitung and briefly informed about the planned actions. Together with his nephew, who happened to be visiting, he was brought to the town hall by his driver Heino Frank, where he had a conversation with the standard leader Friedrich Meyer, which served to coordinate the areas of responsibility. Both were probably informed independently of the events that night. After the conversation, Meyer went to Weener to pass the order on to the leader of the SA, Sturmbannführer Lahmeyer.

Aurich's chain of command ran through SA-Sturmbannführer Eltze from Emden. He first alerted the Aurich district leader Heinrich Bohnens, in order to then go to Aurich accompanied by an SA troop and initiate all further actions there together with Bohnens.

The SA leaders von Esens (SA-Obersturmführer Hermann Hanss), Wittmund (SA-Sturmführer Georg Knoostmann) and Neustadtgödens (SA-Sturmführer Friedrich Haake) were instructed by telephone from the SA-Standarte Emden.

Now the organized pogroms began in all East Frisian towns with a Jewish population, which were later referred to as the “Reichskristallnacht” or the November 1938 pogroms . The synagogues of Aurich , Emden , Esens, Leer, Norden and Weener were destroyed that night . The synagogue in Bunde had been sold to the merchant Barfs before 1938. The Jemgum synagogue had already fallen into disrepair around 1930. A merchant in Neustadtgödens bought the building in 1938 and used the building as a paint store, which is why the Nazis probably didn't start a fire. The preserved building is now used as a memorial and museum. The Norderney synagogue was sold in 1938. Today it is structurally changed and used as a restaurant. The Wittmund synagogue was sold for demolition in June 1938. Only the synagogue of Dornum is preserved today, which was sold to a carpenter on November 7th, 1938.

In Emden, a Jew died as a result of a lung wound that the SA had inflicted on him during the night of the pogrom. All Jews were rounded up and arrested, but women and children were soon released. The male Jews had to clean up under harassment from their guards before they were transferred to Oldenburg. In Oldenburg they were rounded up in the police barracks at the horse market (today the state library). The Jewish people from Oldenburg, who had been herded through the city center to the judicial prison on November 10 in a shameful march, also arrived there.

On November 11th, around 1,000 Jewish East Frisians, Oldenburgers and Bremers were brought to Oranienburg by train via Berlin. Here they were driven out of the trains by SA men the following night and then driven to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp about 2 km away . There were already four deaths on the way to the camp. The Jews then had to stand at the assembly point for 24 hours and were then taken to a barrack, where they had to completely undress. Money and valuables were taken from them a receipt and a personal questionnaire had to be filled, which, as the Oldenburg region Rabbi Leo Trepp reminded, had two words: Dismissed on ..., died on ... .

The Jews remained imprisoned until December 1938 or early 1939. They were only released after they had committed to emigrate.

Exodus, displacement and murder

The Jewish communities were no longer corporations under public law , but were called “Jüdische Kultusvereinigungen e. V. “entered in the register of associations. On February 12 and 13, 1940, the Gestapo attempted to deport the Jews who were still in East Friesland to occupied Poland. The organization abandoned the project due to a lack of transport capacity. In addition, there was massive intervention by the representatives of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany against the project.

An initiative by East Frisian district administrators and the municipal authorities of the city of Emden finally led at the end of January 1940 to instructions from the Gestapo control center in Wilhelmshaven that Jews were to leave East Frisia by April 1, 1940. Only people over the age of 70 were allowed to stay in the Jewish retirement home in Emden. In April 1940, the East Frisian cities and rural communities reported to the district president, earlier than anywhere else in the Reich, that they were "free of Jews". The East Frisian Jews had to look for other apartments within the German Empire (with the exception of Hamburg and the areas on the left bank of the Rhine). Between January and March 1940, on instructions from the Gestapo Wilhelmshaven, 843 Jews from the Aurich administrative district and the state of Oldenburg were forced to leave their places of residence and move to other regions in Germany.

East Friesland was declared free of Jews and was de facto. Remnants of the Jewish population were able to eke out their lives in the Jewish retirement home in Emden. 1941 belonged Emden among the first 12 cities in the kingdom, from which Jews in the East deported were. A few days after the systematic deportations began in October 1941, on October 23, 122 Emden Jews were deported to the Łódź ghetto . 23 people were transferred from the Jewish retirement home in Emden to the Jewish retirement home in Varel (Oldenburg) and from there deported to Theresienstadt in July 1942. Only a few Jews who lived in so-called mixed marriages stayed in East Friesland during the war.

A very large part of the Jews of the Weser-Ems region, who had already been expelled to other parts of the Reich in the spring of 1940, were deported to Minsk on November 18, 1941, where almost all of them were "annihilated by work" or murdered until July 1942 . On July 28 and 29, 1942, around 10,000 Jews (including around 6,500 Russian Jews) were liquidated in Minsk City , presumably including Jews from East Frisia.

Many Jews from East Friesland had emigrated by the end of World War II, but the majority were killed by the National Socialists and their accomplices. The exact number of those murdered cannot be determined; it can be assumed that 1000 Jews were killed in East Friesland, which means about half of the Jews counted in East Friesland in 1925 (2146).

From 1943 on, a freight train from the Westerbork transit camp drove a large group of prisoners via Assen , Groningen and the Nieuweschans border station to the "east" every Tuesday , mainly to the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibór extermination camps . The trip took about three days. The train was supported by Dutch railway staff as far as Nieuweschans, and from there it was taken over by German staff. In Leer, these trains usually stopped for two to three hours at platform 14 of the main station in the middle of the city. There they were guarded by SS men with machine guns.

Exodus refugees in East Frisia

The Exodus was an immigrant ship that played a crucial role in the prehistory of the establishment of the state of Israel in 1947: On July 11, the ship began the crossing in Sète , France, with 4,515 passengers . The trip was monitored from the start by the British secret service. On July 18, the exodus off Haifa was seized by the British Navy in international waters; in the fierce resistance, three of the crew members died and many were injured. The repatriation of immigrants was a high priority for the British administration as it hoped it would send a signal and stop immigration. The measure was called " Operation Oasis " by her .

In the port of Haifa, the exhausted passengers were loaded onto three prisoner ships ( Ocean Vigor , Runnymede Park and Empire Rival ) and sent back to France. They arrived there on July 29th. Although the situation on board was inhumane, most of the passengers refused to leave the ships for three weeks. In order to break the resistance, the British administration threatened to bring the passengers to Germany. After this measure was unsuccessful, the ships put to sea again on August 22nd. As the pressure on the British government increased and they wanted to discuss the decision to deport them to Germany again, the ships made a five-day stopover in Gibraltar at the end of August .

They continued on August 30th and reached the port of Hamburg on September 8th . There, in front of the international press, the passengers were forcibly removed from deck and taken to the “ Pöppendorf ” and “Am Stau” camps near Lübeck , which had previously served to care for members of the Wehrmacht and displaced persons . To intern the passengers, they were converted into prison camps with barbed wire and watchtowers. The international reactions to this way of dealing with people were devastating. Even US President Harry S. Truman stepped in to get the British government to rethink. Resistance continued within the camps as well, which the administration punished, among other things, by reducing food rations.

In 1947, 2,342 Jews interned in the “Pöppendorf” camp were transported by train to former barracks in Emden. In the months after the relocation, many people left the camps in East Friesland; In April 1948, only 1,800 of the 4,000 Jewish people who were once brought to Lower Saxony lived there.

On May 14, 1948, the State of Israel was proclaimed. So the immigration restrictions soon dropped. In mid-July 1948 the Emden camp was cleared after being occupied for almost eight months. The refugees who remained in Emden were transferred to other camps, from where they began their journey to Israel.

Jewish life in East Frisia after 1945

The Jewish inhabitants (and with them the Jewish culture) disappeared from East Friesland in 1942. Only 13 Jews had returned to Emden by 1947. In 1949 they founded a new synagogue community as an association. This dissolved in 1984 because it only consisted of one member.

The last burial at the Jewish cemetery in Emden took place in 2004, in Aurich in 2007. Today hardly any people of Jewish faith live in East Frisia, so the religion is not practiced publicly. The few East Frisian Jews are part of the Jewish community in Oldenburg. In the former East Frisian synagogue communities, working groups were formed to deal with what had happened and to invite survivors. Monuments were erected and the Jewish cemeteries were repaired.

Legal processing

After the end of National Socialist rule, criminal trials in connection with the November pogroms were carried out, especially in 1949/50. These trials existed for almost all places with former synagogue congregations with the exception of Dornum and Jemgum, where the public prosecutor's investigations were insufficient to bring an indictment. In Aurich, one of four defendants was acquitted, the other three were sentenced to three years, one year and ten months in prison.

In Leer there were criminal trials against various responsible persons from the district of Leer from 1948 to 1950, including Oldersumer. They ended with comparatively mild judgments. Most of the imprisonment sentences imposed did not have to be started due to amnesty provisions; many of those responsible were not prosecuted. In the north, the trials against those primarily responsible were held in 1948 and 1951. The court imposed terms of between one and four years in prison in both trials, with seven acquittals and 13 cases being closed.

Synagogue system

The supervision of the 11 East Frisian synagogue communities (and the branch of the Northern community on Norderney) was taken by the municipal authorities or representatives of the communities / areas, the government / Landdrostei in Aurich and the regional rabbinate in Emden. The state rabbinical district of East Friesland comprised the areas of the former principality. In 1844 the state rabbinate was expanded to include the Osnabrück district. The Stade district was also administered by Emden for 10 years towards the end of the 19th century. Wilhelmshaven was also part of the state rabbinical district of East Friesland after the establishment of its own community. The following regional rabbis were active in East Frisia:

| Term of office | State rabbis |

|---|---|

| 1827-1839 | Abraham Lewy Lion Tribe |

| 1841-1847 | Samson Raphael Hirsch |

| 1848-1850 | Joseph Isaaksohn |

| approx. 1852-1870 | H. Hamburger |

| 1870-1874 | Kroner (interim) |

| 1874-1892 | Peter Buchholz |

| approx. 1893-1911 | J. Loeb |

| 1911-1912 | Lewinsky, Hildesheim (interim) |

| 1912-1921 | M. Hoffmann |

| from 1922 | Dr. Samuel Blum |

The next higher authority in the province of Hanover was the Land Rabbi College in Hanover, which consisted of the State Rabbinates of Hanover, Hildesheim and Emden and which met when necessary.

Education

Up until the fall of the Jewish communities during the National Socialist era, there were up to ten Jewish elementary schools in East Frisia. These were maintained by the communities in Aurich, Bunde, Emden, Esens, and for a short time also in Jemgum, Leer, Neustadtgödens (from 1812 to 1922), Norden, Weener and Wittmund. The Jewish schools suffered from strongly fluctuating numbers of pupils and were therefore not always able to maintain regular operations, which is why some schools limited themselves to religious instruction. Elementary classes then take place in public schools. This trend intensified in the 19th century. At that time, liberal-minded Jewish citizens who wanted their offspring to have a good education sent to secondary schools in the cities.

The first Jewish teachers in East Friesland often lived in the households of parents whose children they taught. As a result, they did not need their own letter of safe conduct, but had to be registered with the Prussian War and Domain Chamber in Aurich and received a four-year tolerance. Then they had to look for a new household that they hired and whose board they had to register again. The teachers were forbidden to marry or pursue any other profession. Anyone who married anyway had to expect expulsion from East Frisia, because the teachers, whose situation was precarious until the middle of the 19th century, lacked the means to acquire an escort.

The first Jewish elementary school in East Friesland was opened by the Jewish community in Leer in 1803 on the recommendation of the War and Domain Chamber in Aurich.

With the start of the French territorial rule, the situation changed from 1815. After the French model oversaw a Chief Rabbi (grand-rabbin) the communities in Konsistorialbezirk. He officiated as a regional rabbi from 1827. Under the supervision of the Landdrosten von Aurich and Osnabrück, he controlled and directed the schools of the Jewish communities in these Landdrostei districts and thus had the same powers as the royal consistory, which, as the authority of a Landdrostei, supervised the Christian parishes and their schools. This enabled the state rabbi to intervene directly in the school organization of the communities under his control. After 1815, school sponsorship in the Kingdom of Hanover was basically transferred to the Christian and Jewish communities, and from 1842 the Jewish school system was reorganized. The municipalities were then responsible for the organization and administration as well as the payment of teachers and were obliged to only employ qualified staff. According to a decree of 1831, the language of instruction had to be German. In addition, the subjects Hebrew, Pentateuch in the original language, biblical history and knowledge of religion, German reading, prayers in the original language, orthography, German grammar, writing, arithmetic, geography and world history were taught in Aurich. The Hanover authorities did not raise any objections to the curriculum.

In Emden, the Jewish community opened its first school in 1841 in a building on Judenstrasse (today's Max-Windmüller-Strasse); teaching began in Aurich in 1843. In Weener, the Jewish school was built in 1853 and used until 1924.

Up until the middle of the 19th century, the Kingdom of Hanover regarded the teaching examinations, the employment and dismissal of teachers, school supervision and curricula as internal Jewish matters. From 1848 local authorities and the regional rabbis took over the supervision of the schools. The municipalities continued to finance the teaching staff. In November 1848 the Jewish Teachers' Training Institute in Hanover began its work. Candidate teachers received instruction in the religious subjects of Biblical Studies, Religious Studies, Jewish History and Hebrew, as well as German, history, natural history, geography, writing, arithmetic, drawing and singing. After the annexation of the Kingdom of Hanover by Prussia in 1866, East Frisia became Prussian again. At first, this did not change the school situation. Prussia took over the administrative structures of the annexed Guelph State and only changed them gradually. The land rabbi continued to be responsible for supervising the Jewish schools. He himself was subordinate to the royal consistory, an authority of the Landdrostei responsible for school and church affairs, and later to the royal government at Aurich. The school administration remained the responsibility of the Jewish communities. At some state schools, regular school operations were jeopardized during the First World War due to a shortage of teachers. During this time, the Jewish teacher Lasser Abt took over teaching at the state primary school in Leer, while the Jewish primary school remained closed. The opposite case occurred in Neustadtgödens. While the local Jewish teacher was doing military service, a Catholic clergyman taught the Jewish students. However, religious instruction was generally given by a Jewish religious teacher.

During the Weimar Republic , the organization of the Jewish school system changed little. After the National Socialists came to power in 1933, the Jews in East Friesland suffered repression by state organs. The pupils at German secondary schools were also exposed to isolation and discrimination within their classes and were expelled from schools with the promulgation of the Nuremberg Race Laws in 1935. The Jewish schools in East Friesland became legally private schools, which from 1937 became part of the Reich Association of German Jews. It issued a curriculum for the Israelite schools that also included preparation for emigration, especially to Palestine. In the period that followed, the number of students decreased due to emigration. By 1940 the National Socialists closed the last Jewish schools in East Frisia.

Most of the school buildings have been preserved. In the former Jewish community center and school in Esens, the August-Gottschalk-Haus , a permanent exhibition on the recent history of East Frisian Jews can be seen today. The former Jewish school opened in Leer as a cultural and memorial site in 2013 .

former Jewish school in the north

Development of the proportion of the Jewish population in East Frisia

Due to the statistical data collected at different times, a reliable indication of the number of Jews in East Frisia is only possible for the period from 1833 to 1925. In 1925, the Jews made up 0.84% of the total population of East Frisia. The numerically largest community was Emden with 700 members, Dornum had the highest percentage of the population with 7.3%.

| year | Residents | thereof Jewish | proportion of |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1833 | 153 671 | 2079 | 1.35% |

| 1842 | 167 469 | 2083 | 1.24% |

| 1867 | 193 876 | 2516 | 1.30% |

| 1871 | 193 044 | 2511 | 1.30% |

| 1885 | 211 825 | 2707 | 1.28% |

| 1895 | 228 040 | 2719 | 1.19% |

| 1905 | 251 666 | 2766 | 1.10% |

| 1925 | 290 517 | 2456 | 0.84% |

The following table provides more information on the individual Jewish communities:

| place | First mention of Jewish residents | Number of Jewish residents (years in brackets) | Share of the local population in 1925 in percent | synagogue | graveyard | The End |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aurich | 1636 | 96 (1769); 168 (1802); 288 (1837); 347 (1867); 406 (1885); 370 (1905); 398 (1925) | 6.5 | Kirchstrasse 13; built in 1810 | Emder Strasse; since 1764; Before that, burial in North / East Friesland | November pogrom 1938 |

| Bundles | 1670 | 28 (1867); 55 (1885); 65 (1905); 70 (1925) | 3.5 | built in 1846 | originally in Smarlingen , then Neuschanz , from 1874 in Bunde am Leegweg | Synagogue sold to the merchant Barfs before the November pogrom in 1938 |

| Dornum | 1717 | 10 families (around 1730); 31 (1802); 65 (1867); 61 (1885); 83 (1905); 58 (1925) | 7.3 | High Street; built in 1841 | west of the town center; Acquired in 1723 | Synagogue sold in 1938 before the November pogrom; remained; now a museum; Jewish cemetery (Dornum) |

| Emden | 1571 (1530?) | 6 families (late 16th century); about 100 (1624); approx. 300 (1736); 490 (1741); 501 (1802); 744 (1867); 663 (1885); 809 (1905); 700 (1925) | 2.2 | At Sandpfad 5 (today Bollwerkstraße); first construction probably in the 16th century; New building in 1836; Extension in 1910 | first cemetery (16th century) near Tholenswehr ; since around 1700 Bollwerkstrasse | November pogrom 1938 |

| Esens | 1637 | 73 (1707); 82 (1806); 124 (1840); 118 (1871); 89 (1905); 76 (1925) | 3.4 | Jücherquartier; built in 1827 | On Mühlenweg; acquired in 1701 | November pogrom 1938 |

| Jemgum | 1604 | 4 families (1708); 7 families (1773); 19 (1867); 50 (1885); 20 (1905); 9 (1925) | 0.8 | behind today's house at Lange Straße 62; built in 1810; dilapidated since 1917; 1930 demolished | oldest cemetery in Smarlingen; Own cemetery in 1848 west of Jemgum on the road to Marienchor | Self-dissolution in the 20s of the 19th century |

| Empty | 1611 | 175 (1802); 219 (1867); 306 (1885); 266 (1905); 289 (1925) | 2.4 | from 1793 to 1885 at Horsemarkstrasse 2; New building in 1883/1885 at Heisfelder Strasse 44 | since the 17th century on Leerorter Chaussee | November pogrom 1938 |

| Neustadtgödens | 1639 | 100 (1802); 186 (1867); 139 (1885); 85 (1905); 25 (1925) | 4.4 | built in 1852; Restored in 1886/1887 | 1708 laid out on the Maanlande; Expanded in 1764 | Synagogue sold in 1938 before the November pogrom; today privately owned |

| north | 1577 | 193 (1802); 314 (1867); 253 (1885); 283 (1905); 231 (1925) | 2.1 | Synagogenweg 1; first construction 1804; New building in 1903 | Am Zingel; Jewish burial place probably as early as 1569 - initially also for Jews from Emden, Esens, Aurich and Wittmund | November pogrom 1938 - today: memorial, modeled on the floor plan of the burned synagogue |

| Norderney | 1833 | 6 (1867); 9 (1885); 35 (1895); 88 (1925) | 1.6 | Built in 1878 at Schmiedstrasse 6 | the cemetery in the north was used | Synagogue sold before the November pogrom 1938; today structurally changed and used as a restaurant |

| Weener | 1645 | 11 (1802); 183 (1867); 231 (1885); 175 (1905); 149 (1925) | 3.6 | Built in 1828/1829 at Hindenburgstrasse 32; Renovated in 1928 | from the 17th century to 1848 in Smarlingen , from 1850 to 1896 in Graf-Ulrich-Strasse, since 1896 in Graf-Edzard-Strasse | November pogrom 1938 |

| Wittmund | 1637 | 3 (1643); 8 families (1676); 51 (1710); 16 families (1749); 60 (1802); 93 (1867); 86 (1885); 71 (1905); 53 (1925) | 2.2 | built around 1815/1816 at Kirchstrasse 12 | attested since 1684 on Finkenburgstrasse; New cemetery laid out in 1899/1902 outside Wittmund on Auricher Straße | in June 1938 the synagogue was sold for demolition |

Source : The end of the Jews in East Friesland (see references)

Memorials

After 1945, memorials were set up in all places where there used to be Jewish communities. Most of the time, the Jewish communities are commemorated with memorial stones that stand at the sites of the former synagogues. Several streets were named after Jewish people. The Jewish cemeteries were restored after 1945. In Dornum, the former synagogue has been converted into a memorial with a permanent exhibition on the history of the Dornum Jewish community, among other things.

In 1988, on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Reichspogromnacht, the exhibition “The End of the Jews in East Friesland” was put together by members of the “History of the Jews in East Friesland” working group at the East Frisian Landscape in Aurich. Today it is part of the memorial with a permanent exhibition on the recent history of East Frisian Jews in the “ August-Gottschalk-Haus ”, the former Jewish community center in Esens. The exhibition is organized by the “Ecumenical Working Group Jews and Christians in Esens e. V. “supervised. In Emden, the “Working Group - Jews in Emden e. V. ”was founded, the aim of which is to research the history of the Jewish community in Emden and to convey it educationally. The former Jewish school opened in Leer as a cultural and memorial site in 2013 .

Jewish personalities from East Frisia

- Jacob Emden (1697–1776), rabbi and Talmud scholar

- Recha Freier (1892–1984), resistance fighter against National Socialism , teacher and poet

- Minnie Marx (1865–1929), mother and manager of the Marx Brothers

- Moritz Neumark (1866–1943), industrialist and politician of Jewish origin

- Eduard Norden (1868–1941), classical philologist and religious historian

- Max Windmüller (1920–1945), resistance fighter against National Socialism

See also

- List of former East Frisian synagogues

- List of Jewish cemeteries in East Frisia

- East Frisia at the time of National Socialism

literature

Overall representations

- Heike Düselder (adaptation), Hans P Klausch (adaptation), Albrecht Eckhardt, Jan Lokers, Matthias Nistal: Sources on the history and culture of Judaism in western Lower Saxony from the 16th century to 1945 . Part 1. East Frisia. A relevant inventory. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht 2002, ISBN 3-525-35537-8

- Herbert Reyer (arr.): The end of the Jews in East Frisia. Catalog for the exhibition of the East Frisian landscape on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht . Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1988. ISBN 3-925365-41-9

- Herbert Reyer, Martin Tielke (ed.): Frisia Judaica. Contributions to the history of the Jews in East Frisia . East Frisian Landscape, Aurich 1988, ISBN 3-925365-40-0

- Herbert Obenaus (Ed.): Historical manual of the Jewish communities in Lower Saxony and Bremen . Wallstein, Göttingen 2005, ISBN 3-89244-753-5

Others

- Günter Stein: Stadt am Strom, Speyer and the Rhine , Zechner, 1989, p. 35/36 (mention of Frisians and Jews as long-distance traders in the high Middle Ages), ISBN 3-87928-892-5

- Frank Bajohr : Our hotel is free of Jews. Baths anti-Semitism in the 19th and 20th centuries. Fischer, Frankfurt / M. 2003. ISBN 3-596-15796-X

- Werner Teuber: Jewish cattle traders in East Frisia and northern Emsland 1871–1942. A comparative study of a Jewish professional group in two economically and denominationally different regions. Runge, Cloppenburg 1995, ISBN 3-926720-22-0

- Michael Wildt: He has to go! He must go! - Anti-Semitism in German North and Baltic Sea baths 1920–1935. in: Mittelweg 36th Journal of the Hamburg Institute for Social Research. HIS publ. Ges., Hamburg 4/2001. ISSN 0941-6382

Web links

- Journey to the Jewish East Frisia , publisher: Ostfriesische Landschaft - Kulturagentur, Aurich 2013.

- Land of Discovery. Journey to the Jewish East Frisia. Documentation on the cooperation project , publisher: Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 2014

- Dornum synagogue

- "Max Windmüller Society Emden"

- Jews in Oldersum

- Jewish families in Rhauderfehn

- The German “Ghetto Litzmannstadt” in Lódz, Poland

- bethhahayim.info: about Jewish communities in East Frisia

Individual evidence

- ^ Günter Stein: City on the river, Speyer and the Rhine , Zechner, 1989, p. 35 f. (Mention of Frisians and Jews as long-distance traders in the High Middle Ages), ISBN 3-87928-892-5 .

- ^ Karl Anklam: The Jewish community in Aurich . In: Monthly for the history and science of Judaism . Jew. Kulturbund in Dtschl., Berlin Vol. 71. 1927, No. 4, pp. 194-206.

- ^ Herbert Obenaus (Ed.): Historical manual of the Jewish communities in Lower Saxony and Bremen. Wallstein, Göttingen 2005. ISBN 3-89244-753-5 .

- ↑ The end of the Jews in East Frisia. Catalog for the exhibition of the East Frisian landscape on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht. Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1988, p. 40. ISBN 3-925365-41-9 .

- ^ Herbert Reyer: East Frisia in the Third Reich - The Beginnings of the National Socialist Tyranny in the Aurich District 1933–1938. Ostfriesische Landschaftliche Verlags- und Vertriebsgmbh, Aurich 1992, p. 66; 1999. ISBN 3-932206-14-2 .

- ↑ The end of the Jews in East Frisia. Catalog for the exhibition of the East Frisian landscape on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht. Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1988. ISBN 3-925365-41-9 .

- ↑ Frank Bajohr, 2003 (2nd ed.), P. 117.

- ↑ Jews, gypsies and gangs of thieves become a plague. How Ostfriesland had to defend itself against the influx of foreign servants . In: Excerpt from the Ostfriesische Tageszeitung (OTZ). NS.-Gauverl. Weser-Ems, Emden 1937 (without an exact date).

- ↑ G. Brakelmann: Evangelical Church and the persecution of Jews. Spenner, Waltrop 2001, p. 47f. ISBN 3-933688-53-1 .

- ↑ The end of the Jews in East Frisia. Catalog for the exhibition of the East Frisian landscape on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht. Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 1988. ISBN 3-925365-41-9 , p. 30.

- ↑ We want to smoke the wolf in his canyon! .

- ↑ Herbert Reyer, Martin Tielke, 1988, p. 272.

- ↑ 23.10.41 to Litzmannstadt. Retrieved January 19, 2019 .

- ^ Joachim Liß-Walther: Operation "SS Exodus from Europe 1947". About the fate of the Jewish passengers of the "Exodus 47" , accessed on November 12, 2018

- ^ Herbert Reyer: Aurich . In: Herbert Obenaus (Ed.): Historical manual of the Jewish communities in Lower Saxony and Bremen. Wallstein, Göttingen 2005. ISBN 3-89244-753-5 .

- ^ Lina Gödeken: Around the synagogue in the north. The history of the synagogue community since 1866 . Ostfriesische Landschaft, Aurich 2000, p. 59. ISBN 3-932206-18-5

- ^ Zvi Asaria: The Jews in Lower Saxony. From the oldest times to the present. Rautenberg, Leer 1976. ISBN 3-7921-0214-5 .

- ↑ a b c Gertrud Reershemius: The language of the Aurich Jews: for the reconstruction of West Yiddish language remnants in East Friesland . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-447-05617-5 , pp. 44 .

- ↑ Journey to the Jewish East Frisia. East Frisian Landscape, accessed on February 27, 2020 .

- ^ Rolf Uphoff: History of the Jewish School in Emden. Max-Windmüller-Gesellschaft, accessed on February 27, 2020 .

- ↑ Herbert Reyer, Martin Tielke, 1988, p. 175.