History of the Arabic script

The history of the Arabic alphabet shows numerous changes during its creation. It is believed that the Arabic alphabet was originally borrowed from the Nabataean , a variant of the Aramaic (or perhaps Syrian ) script, which arose from the Phoenician alphabet . From Phoenician, in turn, the Hebrew and Greek alphabets emerged, and from them the Cyrillic and Latin alphabet .

Origins

The Arabic alphabet developed either from the Nabatean or (considered less likely) from the Syrian alphabet. The table shows the changes in the letters from the Aramaic original to the Nabataean and Syrian forms. Arabic is arranged in the middle, so not chronologically to language development.

It seems that the Arabic alphabet arose from the Nabatean alphabet:

- In the 6th and 5th centuries BC North Semitic tribes immigrated and founded a kingdom around the city of Petra , in today's Jordan . These tribes (now known as the Nabataeans, after the name of a tribe, Nabau) believed to speak some form of Arabic.

- The first known written finds of the Nabatean alphabet were made in the 2nd century AD, in Aramaic (the lingua franca of the time), but with some Arabic language properties: the Nabateans did not write the language they spoke. They wrote in a form of the Aramaic alphabet which was constantly evolving; it separated into two forms: the first was primarily used for inscriptions (known as "Monumental Nabatean") and the other form was a cursive, which was quicker and easier to write on papyrus with connected letters . This cursive script influenced the monumental form more and more and gradually changed to the Arabic script.

Pre-Islamic inscriptions

The first Arabic writings date from the year 512 AD. The oldest find is a trilingual inscription in Greek, Syrian and Arabic, found in Zabad in Syria . This version of the Arabic alphabet uses only 22 letters, with only 15 different graphemes, to write down 28 phonemes :

A sufficient number of Arabic inscriptions survived the pre- Islamic era, but very few use the Arabic alphabet. Some are written in Arabic or in its closest sister languages:

- Thamudic , Lihyan , and Safaite inscriptions in the north.

- Nabataean inscriptions in Aramaic and Arabic.

- Inscriptions in other languages, such as B. Syrian .

- Pre-Islamic Arabic inscriptions in Arabic script: these are very few; only five are considered certain. These usually do not use phoneme-distinguishing points, which makes translation very difficult, since many letters coincide in a grapheme.

The table shows a list of Arabic and Nabatean inscriptions that illustrate the beginnings of Arabic.

| Surname | Location | date | language | alphabet | Text & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awdat | Negev in Israel | between 88 and 150 AD | 4 lines in Aramaic, then 2 lines in Arabic | Nabatean with some letter combinations | Thanksgiving prayer to Obodas I, who was worshiped as a god after his death (85 BC) |

| Umm al-Jimal | west of the Hauran Mountains in Syria | around the end of the 3rd century AD | Aramaic-Nabatean | Nabatean, many letter combinations | also Greek, more than 50 fragments |

| Raqush | Mada'in Salih in Saudi Arabia | 267 AD | Mixture of Arabic and Aramaic, 1 vertical line in Thamudic | Nabatean, some letter combinations. Has few diacritical points. | Last inscription in the Nabatean language. Epitaph of Raqush, including instructions against grave robbers. |

| an-namara | 100 km southeast of Damascus | A.D. 328–329 | Arabic | Nabatean, more letter combinations than before | An extensive epitaph of the famous Arab poet and war hero Imru 'al-Qais describes his exploits. |

| Jebel Ram | 50 km east of Aqaba | 3rd century or rather late 4th century AD | 3 lines in Arabic, 1 curved line in Thamudic | Arabic. Uses some diacritical points. | In the temple of Allat . |

| Sakaka | in Saudi Arabia | undated | Arabic | Arabic, some Nabataean influences, and diacriticals. | short; Interpretation unclear |

| Sakaka | in Saudi Arabia | 3rd or 4th century AD | Arabic | Arabic | "Hama son of Garm" |

| Sakaka | in Saudi Arabia | 4th century AD | Arabic | Arabic | "B-`-sw ibn `Abd-Imru'-al-Qais ibn Mal (i) k" |

| Umm al-Jimal | west of the Hauran Mountains in Syria | 4th or 5th century AD | Arabic | similar to arabic | This (document) was drawn up by comrades of 'Ulayh son of' Ubaydah, scribe of the Cohorte Augusta Secunda Philadelphiana ; may he who destroys it go to hell. |

| Zabad | in Syria, south of Aleppo | 512 AD | Arabic | Arabic | Also Greek and Syrian. Christian dedication. In Arabic there is " God's help" and 6 other names. “God” is writtenالاله, DMG al-ʾilāh , see Allah . |

| Jebel Usais | in Syria | 528 AD | Arabic | Arabic | Record of the war campaign of Ibrahim ibn Mughirah on the instructions of King al-Harith (probably al-Harith ibn Jabalah ( Aretas in Greek), king of the Ghassanid , vassal of the Byzantine Empire ) |

| Harran | in the Leija area, south of Damascus | 568 AD | Arabic | Arabic | Greek too. Christian dedication to a martyrion . It describes the construction of the monument by Sharahil ibn Zalim one year after the destruction of Khaybar . |

The Nabataean script gradually changed to the Arabic script. This probably happened in the period between the an Namara inscription and the Jabal Ramm inscription. Most of the evidence is believed to have been on ephemeral material such as papyrus. Since it was a script, it was subject to major changes. Written finds from this period are very rare: only five pre-Islamic inscriptions are considered certain, some others are controversial.

These inscriptions are shown on islamic-awareness.org.

The Nabataean script was designed to write 22 phonemes down; however, the Arabic has 28 phonemes. Therefore, 6 letters of the Nabataean had to be used to represent two Arabic phonemes each:

- d also stands for ḏ ,

- ḥ also stands for ḫ 1 ,

- ṭ also stands for ẕ ,

- ʿAin also stands for ġ 1 ,

- ṣ also stands for ḍ ,

- t also stands for ṯ .

1 Note: The assignment was strongly etymologically influenced, so the Semitic sounds ch and gh became H and ayin in Hebrew .

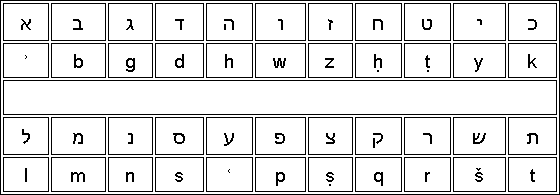

The written Nabataean script developed into the Arabic script, the letters were increasingly connected to one another. Some of the letters became identical to other letters, which led to significant misunderstandings, as shown in the graphic.

There the Arabic letters are listed in the traditional Abdschad arrangement, but for the sake of simplicity they are shown in their current form. Letters with the same grapheme are marked with a colored background. The second sound value of a letter that expresses more than one phoneme follows the comma. In this table, the ǧ stands for English j ( dsch ) such as B. in "June".

In the Arabic language, in the late pre-Islamic period, the g -sound changed completely to j . This does not seem to have been the case with the two tribes that conquered and settled Egypt . In Egyptian Arabic , the letter Jim still stands for the g sound.

Letters at the end of a word were often given an ending loop, so that two or more graphemes developed for many Arabic letters.

- b , n and t became the same.

- y became the same as b , n and t except at the end of the word.

- dsch and ḥ became the same.

- z and r became the same.

- s and sch became the same.

This resulted in only 17 letters with different typefaces. A grapheme represented up to 5 phonemes ( bt th n and sometimes also y ), one represented 3 phonemes ( j ḥ ch ), and 4 each represented 2 phonemes. Compare also the Hebrew alphabet, as in the table:

(A similar situation arose in the Latin script with the capitalized letters I and J in the German Fraktur type : There both letters in common print fonts have the same typeface, but are officially different letters (e.g. sorting order).)

Early Islamic Changes

In the 7th century AD, the Arabic alphabet in its classical form is proven. PERF 558 shows the earliest existing Islamic-Arabic document.

In the 7th century AD, probably in the early years of Islam , while the Koran was being written down, it was found that not all ambiguities in reading the Arabic script could be resolved from context alone. A good solution had to be found. Fonts in the Nabataean and Syrian alphabet already had diacritical points to distinguish between those letters that had collapsed in the grapheme. An example is shown in the table on the right. Analogous to this, a system of diacritical points was introduced for the Arabic script in order to be able to distinguish between the 28 letters of classical Arabic . Partly the resulting new letters were sorted alphabetically according to the non-dotted original letter and partly also at the end.

The oldest surviving written document that undoubtedly uses these diacritical points is also the oldest surviving Arabic papyrus, dated April 643 AD. The points were not mandatory at first, that came much later. Important texts, such as the Koran, were recited very often; This practice, which is still alive today, can probably be traced back to the many ambiguities of the ancient script as well as the lack of writing materials in times when printing was still completely unknown and every copy of a book still had to be made by hand.

The alphabet then had 28 letters in a fixed order and could thus also be used for the digits from 1 to 10, then from 20 to 100, then from 200 to 900 and finally 1000 (see Abdschad ). For this numerical arrangement, the new letters were placed at the end of the alphabet, resulting in the order: alif (1), b (2), dsch (3), d (4), h (5), w (6), e.g. (7), ḥ (8), ṭ (9), y (10), k (20), l (30), m (40), n (50), s (60), ayn (70), f (80), ṣ (90), q (100), r (200), sch (300), t (400), th (500), ch (600), ie (700), ḍ (800), ẓ (900), gh (1000).

The lack of vowel characters in the Arabic script led to further ambiguities: e.g. B. ktb in classical Arabic can mean kataba (“he wrote”), kutiba (“it was written”) and kutub (“books”).

Later, beginning in the latter half of the 6th century AD, vowel signs and hamzas were added. At the same time, vowel characters were also introduced in the Syrian and Hebrew script. Originally a system with red dots was used, which is traced back to the Umayyad governor in Iraq , al-Hajjaj ibn Yūsuf : a point above = a , a point below = i , a point on the line = u ; double dots indicate a nunation . However, this was very tedious and easily confused with the diacritical points for distinguishing the letters. Therefore, the current system was introduced around 100 years later and completed by al-Farahidi around 786 .

Before the historical decree of al-Hajjaj ibn Yūsuf, all important administrative texts (documents) were written down by Persian scribes in Middle Persian and in Pahlavi script. But many of the spelling variants of the Arabic alphabet may have been suggested and implemented by the same scribes.

As soon as new characters are added to the Arabic alphabet, they take the place of the character for which they represent a new alternative: ta marbuta takes the place of the normal t , not h . In the same way, the diacritical marks have no effect on the arrangement: e.g. B. a double consonant, marked by the Schadda , does not count as two single letters.

Some peculiarities of the Arabic alphabet arose from the differences between the pronunciation according to the Koran (which corresponds more to the dialect around Mecca and the pronunciation of the prophet Mohammed and his first followers) and that of the classical standard Arabic . These include, for example:

- ta marbuta : Arose because the -at ending of female nouns (ta marbuta) was often pronounced as -ah but was written as h . To avoid changing the pronunciation of the Quran, the dots of the t were written above the h .

- y ( alif maqsura ) was used to write an a at the end of a word: This came about because a from contraction , where simple y fell out between two vowels, was pronounced in some dialects at the end of the word on the tongue more than other a vowels. This resulted in the spelling y in the Koran .

- a is not in a few words with alif written: The Arabic spelling of Allah was before the Arabs started a Alif as a utterance. In other cases (e.g. the first a in haða = "that") the reason was probably that the vowel was pronounced briefly in the dialect around Mecca.

- hamza : The original Alif referred to the crackling sound . But in the dialect around Mecca the crackling sound was not pronounced, but replaced by w or y or omitted entirely or the associated vowel was lengthened. Between vowels the crackling sound was completely left out and the vowels connected. And the Koran was written in the dialect around Mecca. The Arabic grammarians introduced the diacritical marks for Hamza and used them to mark the crackling sound. Hamza means “tick” in Arabic.

Reorganization of the Arabic alphabet

Barely a century later, Arabic grammarians rearranged the alphabet. Characters with a similar typeface were arranged one after the other to make it easier to teach the script. This resulted in a new arrangement, which no longer corresponded to the old numerical arrangement, which, however, was hardly used over time, as Indian numerals and sometimes Greek numerals are now mainly used.

The Arabic grammarians in North Africa changed the new letters, this explains the differences between the alphabets in the Middle East and the Maghreb countries.

(Greek waw = digamma )

The ancient order of Arabic, as in the other alphabets shown, is known as the Abdjad arrangement . If the letters are arranged in their numerical order, the original Abdschad order is restored:

1 (Greek waw = digamma)

(Note: numerical order here means the original order of letters when used as numerical values. See also Indo-Arabic numbers , Greek numbers and Hebrew numbers )

This arrangement is the most original.

Adaptation of the Arabic alphabet for other languages

As the Arabic alphabet spread to other countries with other languages, more letters had to be introduced to express non-Arabic sounds. Typically, new characters were introduced with three dots above or below:

- Persian and Urdu : p : b with three dots below.

- Persian and Urdu: ch : dsch with three dots below.

- Persian and Urdu: g : k with double bar.

- Persian and Urdu: voiced sch : z (voiced s ) with three dots above.

- in Egypt: g : dsch . The reason is that the Egyptian Arabic g is used, while in other Arab dialects dsh .

- in Egypt: dsch : dsch with three dots below it, is the same as Persian and Urdu Tsch .

- in Egypt: ch : written as t-sch .

- Urdu: retroflex sounds: like the corresponding dentals, but with a small character similar to a Latin letter b above it. (The same problem arose long before with the adoption of the Semitic alphabet for the Indian language: see Brahmi .)

- In Southeast Asia: ng as in “sing”: ch or gh , each with three dots above instead of just one.

- Michael Cook shows an example of tsch ( Polish cz ) written as s with three dots underneath, in an Arabic-Polish bilingual Koran for Muslim Tatars living in Poland .

Abolition of the Arabic script in non-Arabic countries

Since the beginning of the 20th century, various non-Arabic countries have stopped using the Arabic script and have mostly switched to the Latin script. Examples are:

| Area of use | Arabic alphabet | New alphabet | date | Abolition by order of |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Some republics of the Soviet Union | Mostly Turkic languages and other Muslim peoples with Persian-based writing systems, later the Ottoman-Turkish alphabet with modifications | Latin alphabet with partly newly created special letters , from 1939 Cyrillic | 1920-1929 | Modernization efforts after the October Revolution ; Change to Cyrillic script in 1939 on the instructions of the Kremlin |

| Malaysia | Jawi script (which is still widely used in Brunei and Pattani ) | Latin alphabet | 19th century | British colonial administration |

| Turkey | Ottoman-Turkish alphabet | Turkish alphabet (Latin alphabet with special letters) | 1928 | Government of the Republic of Turkey after the fall of the Ottoman Empire |

| partly in Albania | Ottoman-Turkish alphabet | Latin alphabet with Albanian special characters and double letters | 1908 | Monastir Congress , Albanian writers and politicians agree on the use of the Latin alphabet, previously Albanian was written in Greek and Arabic |

| Somalia | Wadaad script | Latin alphabet | 1972 | Dictator Siad Barre |

See also

credentials

- ^ A First / Second Century Arabic Inscription Of ʿEn ʿAvdat. May 31, 2005, accessed December 29, 2018 .

- ^ David F. Graf, Salah Said: New Nabataean Funerary Inscriptions from Umm al-Jimāl . In: Journal of Semitic Studies . Volume 52, Issue 2, October 1, 2006, pp. 267–303 (English, oxfordjournals.org [accessed December 29, 2018] Information is contained in the abstract of said article).

- ↑ Raqush Inscription (Jaussen-Savignac 17): The Earliest Dated pre-Islamic Arabic Inscription (267 CE). March 6, 2005, accessed December 29, 2018 .

- ↑ Namarah Inscription: The Second Oldest Dated pre-Islamic Arabic Inscription (328 CE). May 5, 2005, accessed December 29, 2018 .

- ↑ a b Two Pre-Islamic Arabic Inscriptions From Sakakah, Saudi Arabia. May 31, 2005, accessed December 29, 2018 .

- ^ A Pre-Islamic Arabic Inscription At Umm Al-Jimāl. May 16, 2005, accessed December 29, 2018 .

- ↑ Jabal Usays (Syria) Inscription Containing First Line Of The Throne Verse (Qur'an 2: 255), 93 AH / 711 CE. May 3, 2005, accessed December 29, 2018 .

- ↑ Harran Inscription: A Pre-Islamic Arabic Inscription From 568 CE. January 29, 2008, accessed December 29, 2018 .

- ↑ The Arabic & Islamic Inscriptions: Examples Of Arabic Epigraphy ( English ) Islamic Awareness. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Michael Cook: The Koran, A Very Short Introduction . Ed .: Oxford University Press . 2000, ISBN 0-19-285344-9 , pp. 93 (English).

- ↑ Nurlan Joomagueldinov, Karl Pentzlin, Ilya Yevlampiev: Proposal to encode Latin letters used in the Former Soviet Union . January 29, 2012 ( dkuug.dk [PDF; 19.3 MB ; accessed on December 29, 2018]).

- ↑ Jala Garibova, Betty Blair: Arabic or Latin? Reform for the Price of a Battleship - Debates at the First Turkology Congress hosted by Baku in 1926. In: Azerbaijan International . Retrieved December 29, 2018 .