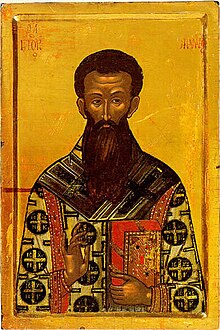

Gregorios Palamas

Gregorios Palamas ( Greek Γρηγόριος Παλαμάς ; * late 1296 or early 1297 in Constantinople ; † November 14, 1359 in Thessalonike ) was a Byzantine theologian , writer and archbishop of Thessalonica. He was canonized in 1368 and is one of the highest authorities in the Orthodox churches .

His doctrine, palamism , was the last advancement of Orthodox theology that was declared binding. One of the main characteristics of palamism is its distinction between a being of God, in principle inaccessible to creatures, and the energies of God with which God reveals himself. According to his essence, God remains, even if he willingly turn to the nondivine, always different from his own turn and unknowable. In contrast, in his deeds, that is, in his energies, God can be known and experienced. Palamas considers these energies as uncreated just like God's being.

With the distinction between the essence and energies of God and the assertion of the imperfection of the energies, Palamas theologically defends so-called hesychasm , the prayer practice of the Athos monks, of which he himself belonged. Hesychasm is based on the assumption that the uncreated Tabor light can be seen by man, with which God can be perceived in his energies. Palamas' opponents, on the other hand, believe that there are only created effects outside of God's uncreated being.

Life

Youth and early phase of monastic life

Gregorios Palamas came from a noble family of Asian Minor origin; his father, the Senator Konstantin Palamas, was a confidante of the Byzantine emperor Andronikos II. and tutor of his grandson, the future emperor Andronikos III . Gregorios came into close contact with monks as a child. When he was seven years old, his father died. Then Andronikos II took responsibility for his upbringing, and Gregorios grew up together with Andronikos III of the same age. in the imperial palace. He received his higher education under the direction of the prominent scholar Theodoros Metochites . It consisted primarily of studying Aristotle's writings on logic. Gregorios thought little of the study of ancient philosophy; he suggested that one should only study it for as long as necessary and then turn to theology as soon as possible. He considered secular studies incompatible with the life of a monk, for which he was preparing.

He became a monk at the age of about twenty and also persuaded his mother and four younger siblings to adopt a monastic lifestyle. He and his two brothers settled on Mount Athos, where they placed themselves under the direction of a hesychast named Nicodemus, who lived near the Vatopedi monastery . For three years, until the death of Nicodemus, Gregorios occupied himself with ascetic exercises. Then he moved to the Megisti Lavra Monastery . After three years he entered the Skite Glossia. He stayed there for two years. Under the direction of a famous master named Gregorios the Great, he studied the practice of hesychasm. Around 1325 Turkish raids forced Gregorios Palamas and other monks who lived outside the fortified complexes of the great monasteries to leave Mount Athos. First he went to Thessalonike, where he was ordained a priest in 1326. He later retired with ten other monks to a hermitage on a mountain in the area of Berrhoia (now Veria ), where he practiced asceticism and hesychasm for another five years. According to the Hesychastic tradition, he spent five days a week in complete solitude in silence; on Saturdays and Sundays he devoted himself to talking to the confreres. So he practiced a middle ground between pure hermit life and monastic community.

When Serbian raids made life on the mountain unsafe, Gregorios returned to Mount Athos, where he settled in the hermitage of St. Sabas and continued his usual rhythm of life. For a time he was Hegoumenos (abbot) of the Esphigmenou monastery , where two hundred monks lived, but then he returned to St. Sabas. Around 1334 he began his writing activity; he wrote a saint's life and treatises on theological topics and questions of monastic life. Two of the treatises he wrote at the time deal with the outcome of the Holy Spirit , a major point in the theological conflict with the Western Church. This topic was topical at the time because of the negotiations on reunification with the Western Church (church union).

Beginning of the conflict over hesychasm

Around 1330 the monk and humanistic philosopher Barlaam came from Calabria to Constantinople. There he was involved in union talks with papal envoys on the side of the Greeks in 1334. As a representative of the neo - Platonic negative theology of the Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita , he considered all positive claims about God to be questionable. He therefore denied that statements can be made about the outcome of the Holy Spirit, the main point of dispute between the Eastern and Western churches, which can be shown to be philosophically correct. He pleaded for following the view of the church fathers and for the rest to leave the question, which cannot be resolved with arguments, to private theological speculation. Gregorios Palamas, whom his friends asked for a statement, advocated the opposite position. According to her, God, whom negative theology considers unknowable, not only revealed himself to the apostles and church fathers, but also continues to reveal himself to the church through the voices of competent theologians. Accordingly, reliable statements about him are possible and are to be regarded as binding truth. The claims of non-Christian philosophers, however, should not be trusted.

In Thessalonica, Barlaam learned about the prayer style of the hesychastic monks, with which an attempt was made to achieve a vision of God by means of a meditation technique and even to let the human body participate in divine grace. He viewed this behavior as the scandalous arrogance of uneducated monks, whom he referred to as omphalopsychoi (“people with the soul in the navel”) because in hesychastic meditation attention was drawn to the navel ( navel gaze ). In 1338 Barlaam tried in vain to get the ecclesiastical authorities to intervene against the Hesychastic Athos monks in Constantinople. The result was that the patriarch forbade him to polemics against the monks. Barlaam did not follow this instruction but returned to Thessalonica and continued his attacks on the monks.

This began the dispute over hesychasm, in which Palamas took over the defense of the Athos monks. There were personal encounters between Barlaam and Palamas, but attempts to resolve the conflict failed. Palamas wrote the Triads , three groups of three treatises each on the theological justification of hesychasm. Barlaam published a reply to the first triad and continued his efforts to achieve ecclesiastical union in which the main issue at issue should not be fixed. For this purpose the emperor sent him to Avignon to negotiate , but Barlaam did not have a church mandate and achieved nothing.

In the further course of the dispute, the relevant authorities of the Athos community sided with Palamas. They signed Tomos hagioreitikos , written by him or on his behalf , who condemned Barlaam's position without mentioning the opponent by name. With this, monks anticipated a doctrinal decision that, according to the traditional view, only belonged to a synod. New meetings between the two opponents were again unsuccessful. In a pamphlet Against the Messalians , Barlaam attacked Palamas personally for the first time and accused him of the heresy of Messalianism .

Councils of 1341

In 1340 Barlaam began a campaign in Constantinople with the aim of winning over influential circles for an ecclesiastical condemnation of the theology of Palamas. His supporters were able to get the convening of a council summoning Palamas. Emperor Andronikos III, who was a childhood friend of Palamas, and Patriarch John XIV. Kalekas wanted above all to avoid a dogmatic dispute that could endanger peace in the empire and the Church. With regard to the theological controversy, the patriarch took an unclear, wavering attitude; he wanted to end the conflict as inconspicuously as possible through disciplinary measures in order to evade a substantive statement. This was also the aim of the emperor's policy; Andronikos forbade Barlaam to accuse Palamas of heresy. This course of pacification and appeasement by the highest state and church authorities ultimately worked in favor of Palamas, because Palamas defended the status quo , while Barlaam was the aggressor and sought change.

The council met on June 10, 1341 under the presidency of the emperor in Hagia Sophia ; its session lasted only one day and few bishops attended. First Barlaam was heard as a prosecutor, then Palamas. Barlaam had to realize that the majority was against him. He felt compelled to retract his view as erroneous and to ask for forgiveness, which was willingly granted him. So the council ended with general reconciliation based on Barlaam's surrender. For Palamas, however, it was not a complete victory, because the condemnation of the position of his opponent did not necessarily mean that the council fully supported his teaching. Immediately after the end of the council, the patriarch forbade possession of Barlaam's antihesychastic writings and ordered all copies to be handed over to the ecclesiastical authorities.

A few days after the council meeting, the emperor died. Barlaam then started his attacks again. But he found so little support that he decided to leave the empire and emigrate to the West. The monk and theologian Gregorios Akindynos , who had previously assumed a mediating position, became the new main opponent of Palamas . Akindynos accepted the hesychastic prayer practice, but opposed its theological justification by Palamas. In August 1341 a second council met, which confirmed the resolution of the first and condemned Akindynos.

Theological dispute in the Byzantine civil war

The late emperor Andronikos III. left a nine-year-old heir, Johannes V. A dispute broke out over the reign between the patriarch Johannes Kalekas and the powerful nobleman Johannes Kantakuzenos . After a provisional reconciliation, Kantakuzenos left the capital, whereupon the patriarch prevailed in a flash. Thereupon Kantakuzenos was proclaimed emperor, but he continued to recognize the entitlement to claim the throne of John V, whose co-regent he wanted to be. The conflicts between the two then led to a civil war and on November 19, 1341, the Patriarch crowned Johannes V as sole emperor.

Palamas, who was in Constantinople, campaigned for a settlement; he did not take sides explicitly, but his sympathy for Kantakuzenos was unmistakable. In doing so he made the patriarch an enemy. The patriarch began playing the convicted monk Akindynos against Palamas. To avoid the political turmoil, Palamas withdrew to the monastery of St. Michael in Sosthenion near the capital, but he refused to drop Kantakuzenos. He wrote new writings to justify his position in the conflicts over his theology. The patriarch, who had forbidden a continuation of the controversy over hesychasm, reproached him for this. In 1343 Palamas was arrested; the reason for this was not his theological activities, but the suspicion that he was supporting the rebel Kantakuzenos. At the instigation of the Patriarch he was taken into custody in Constantinople. However, he was later taken to the prison of the Imperial Palace because the reason for his detention was political and not theological; therefore he was allowed to continue his work as a theological writer in prison. The affairs of government were now in the hands of Empress Anna, the mother of John V, who, although agreed with the patriarch in opposition to Kantakuzenos, otherwise represented her own interests.

The patriarch now appeared more and more resolutely as the theological opponent of Palamas and gave Akindynos an increasingly free hand to attack Palamism. At the end of 1344 he had the imprisoned Palamas expelled from the church. In the meantime, numerous theologians and church dignitaries had taken a stand for or against palamism, and key positions in the church hierarchy were filled from the point of view of taking sides in the dispute over palamism. Some bishops took a vague or wavering attitude. It was not all monasticism that stood behind the Palamites; rather, there was also a strong opposition to Palamism among the monks. The conflict over palamism and that over imperial dignity overlapped, but not all opponents of Kantakuzenos were supporters of the patriarch and Akindynos, and not all supporters of Kantakuzenos were Palamites.

The patriarch succeeded in expanding his position of power to such an extent that he dared to ordain Akindynos as a deacon and priest in order to open the way for him to episcopal dignity and thus to give him theological authority. Up until now Akindynos had been a simple lay monk (most monks in the Eastern Churches are not ordained priests). With this step, however, the patriarch came into conflict with the empress and her court, because Akindynos had been condemned as a heretic by a council under Emperor Andronikos III, Anna's deceased husband.

Meanwhile, Kantakuzenos began to gain the upper hand in the civil war. Under these circumstances, Empress Anna approached the Palamite camp. Finally she decided to sacrifice the patriarch who had exposed himself through the consecration of Akindynos. In January 1347 she convened a council that confirmed the council resolutions of 1341 against Barlaam and deposed the patriarch for having ordained a convicted heretic. This removed the main obstacle to an understanding with Kantakuzenos. On February 2, 1347, Kantakuzenos' troops occupied the capital. The Empress then took Palamas out of prison and sent him as her envoy to the conqueror to negotiate an agreement. Kantakuzenos became generally recognized emperor ( John VI. ) As co-ruler of the now fifteen-year-old John V.

Palamas as victor and archbishop of Thessalonica

With the military victory of Kantakuzenos, the final theological triumph of Palamism began, which now prevailed on a broad front in the empire after its most prominent opponents had been condemned and thus discredited by binding council resolutions. At the beginning of 1347, two more councils confirmed the earlier decisions in quick succession. A decisive decision was the installation of the zealous Palamite Isidoros as the new Patriarch of Constantinople on May 17, 1347. Immediately after his election, Isidorus consecrated 32 new bishops, including Palamas, who became Metropolitan of Thessalonike and thus received the second most important position in the Byzantine Church. The new bishops had to make a creed by which they professed palamism.

Nevertheless, there was still resistance to the new balance of power and thus also to Palamas and Palamism. The discontent, which went up to open rebellion, was fed by different motives. Partly it was about opposition to the person of the new patriarch or against the rise and growing influence of hesychastic monks in the church hierarchy, partly opposition to Kantakuzenos was the driving force. The latter was the case in Thessalonica. There an anti-noble movement of the poorer classes had triggered a revolt against the powerful and rich. The bitterness of the rebels who came to power was particularly directed against the supporters of the Kantakuzenos, who was considered a main representative of the high nobility. Therefore, Thessalonike refused to recognize the new emperor and to accept his ally Palamas as archbishop. This opposition was not directed against hesychasm. It was not until the beginning of 1350, after Kantakuzenos had asserted himself militarily in Thessalonica, that Palamas could take office.

In Constantinople the Antipalamites found a new leader, the theologian Nikephoros Gregoras . Nikephorus had successfully disputed Barlaam and stayed out of the dispute over Akindynos, but in 1346 he took a position in a polemic against Palamas. Thereupon none other than the Byzantine regent Anna of Savoy took over the defense of Gregorios Palamas. In 1351 a new council was called. It met under the chairmanship of Emperor John VI, had more participants than the previous ones and was dominated by the now victorious Palamites. Nevertheless, the minority of the anti-Palamites, including Gregoras, were able to present their arguments. The meeting ended with a commitment to the core of Palamism and the condemnation of the anti-Palamites, if they showed no repentance. The leaders of the anti-Palamite forces were then arrested or placed under house arrest. A second council in the same year, attended only by Palamites, completed the triumph of Palamism by resolving six fundamental theological questions in the Palamitic sense. Both emperors signed the council resolutions. The principles of palamism were included in the Synodicon of Orthodoxy , a summary of Orthodox teaching, with which the Byzantine Church finally adopted palamism as an officially binding doctrine. The adversaries of palamism were solemnly cursed. This decision was subsequently adopted by the other Orthodox churches.

Palamas spent most of the last years of his life in his episcopal city of Thessalonica. From 1352 he suffered from the disease from which he later died. Emperor Johannes V resided in Thessalonike with his mother Anna; from there they organized a new resistance against John VI, who ruled Constantinople. Kantakuzenos. John V asked Palamas to mediate in the newly erupted conflict. On an imperial warship, Palamas set out to meet his old ally, Kantakuzenos. Unfavorable weather forced the ship to land near Gallipoli , where the Turks, who already ruled the area, captured the archbishop and his entourage.

As with many other hesychasts, Greek patriotism was weak in Palamas. He did not dream of a reconquest of Asia Minor, but was ready to put up with the victory of Islam indifferently. The letters he wrote from captivity in Turkey reflect this attitude. It was very different from the attitude of the Byzantine humanists. As patriots, the humanists were ready to make concessions to the Western Church on questions of faith in order to win military support against the advancing Turks. The Palamites, on the other hand, viewed the rule of non-Christians over Christians as a normal condition to be accepted. Ultimately, only the religious questions were essential for them. In doing so, they contributed to the defeatist mood in the Byzantine Empire. Palamas was ransomed and went to Constantinople. There, in the meantime, Johannes V had prevailed against his adversary. A dispute between Palamas and Nikephoros Gregoras in the presence of the emperor and a papal legate ended with no tangible result. In the summer of 1355, Palamas returned to Thessalonica. He and Gregoras continued their polemics in new pamphlets. On November 14, 1359, Palamas succumbed to his illness. He was buried in the Sophienkirche , the cathedral of Thessalonike.

Teaching

Palamas never presented and justified his teaching comprehensively as a system, but only wrote a brief summary, the "150 chapters", and a creed. This fact is related to his fundamental skepticism towards a scientifically based theology or metaphysics. The focus of his extensive work (135 titles) lies in the field of dogmatic polemics . In the 63 sermons he has received, hesychasm is only marginally discussed. Therefore, the lesson must be derived from his polemical writings and his letters, which refer to current individual questions. Palamism as a complex of some theological convictions is clearly defined by the council decisions.

Key messages of palamism

Palamism can be summarized in the following six key statements of the Palamitic Council of Constantinople held in the summer of 1351:

- In God there is a difference between beings (Greek οὐσία ousía ) and energies (Greek ἐνέργειαι enérgeiai ).

- Both the being and the energies are uncreated.

- From this distinction, however, it does not follow that God is something composed of different elements (Greek σύνθετον sýntheton ), because although the difference is real, we are not dealing with two ontologically independent realities. Rather, both terms refer to only one simple God who is fully present in both his being and in each of his energies. The difference is that one term (being) refers to God from the point of view of his incomprehensibility from the point of view of creatures and the other (energies) to God in terms of the fact that he reveals himself to creatures.

- The energies can be referred to with the term “deity” without God becoming two gods. This also corresponds to the language used by the Church Fathers .

- The statement "God's nature surpasses (Greek ὑπέρκειται hypérkeitai ) the energy" is correct and in accordance with the teaching of the Church Fathers.

- Real participation (Greek μετοχή metochḗ ) in God is possible for humans . However, this does not refer to the divine being, but to the fact that divine energy is actually revealed to man and thus made accessible.

Relationship to philosophy

One of the main characteristics of palamism is its sharp contrast to a philosophical current whose most prominent spokesman is Palamas' opponent Barlaam. In modern terminology, this trend is often referred to as "humanistic" (in the sense of Western Renaissance humanism ). Barlaam stands in the tradition of ancient Neoplatonism and the associated negative theology . In doing so, he refers in particular to the late antique theologian Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita , who enjoyed great esteem in both the Eastern and Western churches, and emphasizes his agreement with non-Christian ancient philosophers with regard to divine transcendence . Barlaam makes a sharp distinction between the area of the uncreated (God), which as such is in principle closed to human thought and also to all human experience, and the area of created things as a legitimate field of activity of the mind. In the field of worldly knowledge, for Barlaam Plato and Aristotle are authorities of the highest rank, just as the Bible and the Church Fathers are in theology. Because of the inaccessibility of God, the theological statements about him - for example with regard to the disputed questions between the Western and Eastern churches - are hardly more than mental games. God can only be known through the world he has created, since only it can be perceived; in addition, only negative statements that determine what God is not make sense. Therefore, for Barlaam, philosophy (by which science as a whole is meant) is the best that the person who wants to know has at his disposal. This applies equally to non-Christian as to Christian philosophy, because there is only one wisdom that all philosophers strive for and can achieve.

Palamas counters this with his conviction that non-Christian ancient philosophy can in no way represent a way to God. The aspirations of the ancient philosophers - Plato and Aristotle as well as the Neoplatonists - were misguided because they were not supported by divine grace. Man is in principle incapable of reaching God by means of his own efforts on a philosophical path. The knowledge that science reveals to him is basically insignificant, even insofar as it is true, since it does not contribute to salvation. The assumption of Platonic ideas as cosmological causes is nonsensical, because if ideas of things in the Spirit of God are a prerequisite for the creation of these things, one must also assume that these ideas in turn presuppose ideas of ideas, which leads to an infinite regress . The ancient Neo-Platonists, who write of divine or superhuman beings to whom man in need of redemption can turn, were misled by demons. In general, the ancient gods and also the daimonion of Socrates are not imaginations, but real beings, namely angels of the devil.

The logic of Aristotle could not even help man to make an apodictic statement about something created, because its conclusions are dependent on premises that are ultimately based on sensory perception. Since human sensory perception is limited, it cannot even lead to certain knowledge about a worldly object of knowledge, because not all the necessary facts are accessible to it. Even more so she is incapable of making statements about divine transcendence ; this only reveals itself to religious experience. Any Aristotelian argument presupposes the phenomena to which it relates. The phenomena are primary and their investigation by logic is always secondary. It is pointless to look for a starting point for Aristotelian arguments in time, because a search in the past can only lead to earlier phenomena. The logic is dependent on the understanding of the human being, which emerged as the last of the creatures.

Hesychastic practice

A central element of hesychasm is the view that not only the soul, but also the human body has to participate in the prayer leading to knowledge of God. This is expressed in the established hesychastic prayer practice, which includes body-related regulations such as concentrating on the navel and a special regulation of the breath. According to this concept, the body is even involved in seeing God and thus has access to the Godhead. This inclusion of the body is in contrast to the traditional (new) Platonic teaching, which classifies the cognitive process as a purely spiritual process and evaluates the body as a mere obstacle that opposes the soul's ascent to the vision of the divine through its material nature.

Barlaam criticizes hesychasm with the argument that the involvement of the body leads to the soul turning to it and, if it loves body-related activities, being filled with darkness. Palamas counters this with his assertion that through its inclusion in a hesychastic spirituality, the body does not hinder or pull the soul down; rather, he is lifted up through his actions in common with the soul. The spirit is not bound to the flesh, but the flesh is raised to a dignity that is close to that of the spirit. In the spiritual human being, let the soul impart divine grace to the body. This enables the body to experience the divine, through which it then experiences it just like the soul. Under this impression the body gives up its tendency to evil and now strives for its own healing and deification. An example of this are the tears of repentance that the body sheds. If the body had no part in spiritual practice, it would also be superfluous to fast or pray on knees or to stand upright, for all such activities of the body would then only be undesirable distractions of the soul from its task. To reject is that which is caused by the specifically physical pleasures and influences the soul through pleasant sensations. But what is brought about by the soul in the body when it is filled with spiritual joy is a spiritual reality, also insofar as it affects the body. Purification of the mind alone is insufficient. Although it is easily possible, it is then naturally easy to relapse into the previous state. A permanent cleansing is preferable to it, which includes all abilities and powers of the soul and the body.

Palamas emphatically contradicts the other side's claim that hesychastic prayer consists of the mechanical application of a technique aimed at producing spiritual results and thus forcing divine grace. He describes these allegations as defamatory. Rather, the purpose of the body-related regulations is only to create and maintain the essential concentration. This is particularly important for beginners.

Another point of criticism concerns the uninterrupted "monological" prayer that the hesychasts practice with reference to the Bible passage 1 Thess 5:17 EU ("Pray without ceasing!"). From Barlaam's point of view, this is a passive, quietistic state. To this, Palamas replies that this prayer is rather a conscious activity of the person who thereby also expresses his gratitude. It is not about moving God to something, because God always acts of his own accord, and also not about drawing him to the prayer, because God is everywhere anyway, but the prayer rises to God.

An essential part of the hesychastic experience, the details of which Palamas only goes into in passing, are the monks' visions of light. The praying hesychasts believe they perceive a supernatural light that they equate with the light in which, according to the Gospels, Christ was transfigured on a mountain . This light is called Tabor light because, according to extra-biblical tradition, the mountain is Mount Tabor .

Theory of knowledge of God

The theory of the knowledge of God forms the core of Palamas' teaching, because it is about his main concern, the defense of hesychastic practice against criticism, it proceeds from false assumptions about the knowledge of God. Particularly offensive to the opponents of hesychasm and palamism is the assertion that what the praying hesychast experience is nothing less than an immediate experience ( πείρα peira ) of God in his uncreated reality. In the opinion of the critics, the inclusion of the body in the hesychastic vision of God amounts to the assertion that the immaterial and transcendent God can be seen with earthly eyes - a monstrous idea for the antihesychast. The focus of the criticism is the assumption of the hesychasts that the light they claim to see is uncreated and therefore divine. Barlaam opposes this with the view that every light that can be perceived by humans, including Tabor light, is a sensual, transitory phenomenon. The Tabor light can only be called divine insofar as it is a symbol of the divine.

Palamas considers the existence and uniqueness of God to be necessarily provable, but substantive statements about his being are impossible. Despite the inaccessibility of God's nature, he believes that an immediate experience of God is fundamentally possible for every Christian thanks to God's self-revelation. He creates a theoretical basis for this assertion with the distinction between God's inaccessible being and his revealed and therefore experiential energies (active forces). This distinction is meant as a real one, that is, not as a mere conceptual construct that the human mind, seeking understanding, needs. Therefore, in the polemics of his opponents, Palamas is accused of “two-gods” (ditheism) or even “polytheism”. He assigns the energies as well as the being to the realm of the uncreated. He declares that the simple, indivisible God is as fully present in each of his uncreated energies as in his own being. This makes it conceivable that human experience also extends to the realm of the uncreated, insofar as this reveals itself. In this way, the ontological gap between Creator and creation is bridged in a certain way. Although Palamas emphasizes this gap between the uncreated (God's essence and energies) and the created (the entire creation), thereby distancing himself from the Neoplatonic model of a gradual emanation (outflow) of the deity into the world, epistemologically he needs a bridging.

By placing the Tabor light among the uncreated energies of God, Palamas can understand the vision of light as a vision of God. With this he is reacting to Barlaam's criticism that the hesychasts regard the Tabor light as a divine substance. He counters the reproach that he considers God to be perceptible through the senses that the hesychastic vision is not sensual because it is not received through the senses. In reality it is not sensory perception, because the hesychast does not see the light through his body but through the Holy Spirit.

According to the Palamitic doctrine, energies also include uncreated grace ( χάρις ἄκτιστος cháris áktistos ), which is distinguished from created grace, as well as God's goodness and life. The ability of the saints to perform miracles is due to an uncreated power working within them, for otherwise it would be natural processes. Thus in the saints there is something uncreated. With this consideration, Palamas arrives at the shocking statement for his opponents that the human being deified by grace attains the status of an uncreated one by grace. The deified human being is thanks to his participation "God by grace", God's life becomes his life, God's existence his existence.

With such bold formulations, however, Palamas does not introduce a completely new doctrine, but rather relies on the authority of the highly respected church writer Maximos Homologetes in key points . In other ways too, both sides like to refer to generally recognized theological authorities in the conflict and accuse the other side of deviating from tradition and heresy . The Antipalamites name the alleged apostle student Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita as key witnesses for the correctness of their positions.

Palamas describes the energies as real things ( πράγματα prágmata ) in the sense that the terms used for them are not empty words, but not in the sense that they have an independent existence. They are inseparable from God's essence. In some ways they are identical with her, in others not; in some ways they are accidental , in others not. They are something other than the Holy Spirit and cannot be called attributes of God. Palamas calls the inaccessible essence of God “upper deity”, the energies “descending deity” (which is not meant in the sense of “lower” or “lower” deity); this is interpreted by the opposing side as a deviation from Christian monotheism. His hesitant attitude in his attempts to circumscribe the energies reveals his dilemma. In his disputes with philosophically arguing opponents, he relies on the unrivaled instrument of Aristotelian terminology, although he is convinced that philosophical thinking and philosophical concepts are fundamentally unsuitable for describing divine reality.

The knowledge of God gained through contemplation ( contemplation , Greek θεωρία theoría ) is not knowledge for Palamas or can at most be described as such in a metaphorical , improper sense; rather, he considers it to be far superior to all knowledge.

reception

Soon after his death, Palamas was worshiped in many places. In 1368 the canonization followed by the patriarch Philotheos Kokkinos , an ardent palamit. Palamas' name and his teaching entered the Synodicon of Orthodoxy in 1352 , which is read on the Sunday of Orthodoxy (1st Sunday of Lent). The second day of fasting and the day of his death were set as his feast days.

Palamas experienced a wide reception in Greek Orthodox theology in the 14th and 15th centuries. From 1347 his students and their pupils held high and highest ecclesiastical offices, including that of the Patriarch of Constantinople. Anti-Palamite positions were no longer tolerated in the Byzantine Empire after its final victory; leading anti-Palamites went into exile and converted to Catholicism. Outside the sphere of influence of the Byzantine emperor - in Russia, Syria and Cyprus - the resistance to palamism persisted for a long time. In 1439, palamism, as a binding teaching of the Orthodox Church, was a potential obstacle to the union negotiations between Western and Eastern Churches at the Council of Florence . The problem was circumvented by the Byzantine side strictly refusing to discuss it. Eventually, formulations were found that could be interpreted in both a Catholic and a Palamitic sense, and an explicit condemnation of Palamism was avoided. During the Turkish occupation there are relatively few explicit references to Palamas, but his teaching remained unchallenged as the official theological position of the Greek Orthodox Church.

Palamism and hesychasm received new impulses from the Russian Imjaslavie movement ( worship of the name of God) in the 19th and early 20th centuries , which have continued to be effective into our century. The Congress of Orthodox Theologians held in Athens in 1936 led to a renaissance of palamism, which was further developed and redesigned primarily by Jean Meyendorff . These endeavors, known as New Palamism, were propagated by their proponents as a return to the roots and the true identity of Orthodoxy. From a neo-Palamite point of view, Gregorios Palamas appears as "the greatest theologian of the Eastern Church in the second millennium".

Palamas' writings are reissued in the complete edition (Gregoriou tou Palama Syngrammata) begun in 1962 ; some are still unedited, many not yet translated into modern languages.

Since the 20th century, theologians and church historians have been arguing - often influenced by the viewpoints of modern theology - over the question of whether palamism is to be regarded as the development and further development of the Greek theology of patristicism , as Palamas himself said, or whether it is a fundamental innovation in order to act as a breach of tradition, as the standpoint of the medieval and modern opponents of Palamism reads. Orthodox theologians such as Meyendorff and Vladimir Lossky advocate the continuity thesis; to the proponents of the opposite opinion include u. a. Gerhard Podskalsky and Dorothea Wendebourg. From a denominational point of view, in the ongoing debate between Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox theologians, the question of continuity appears as a question of legitimacy. From the orthodox side it is argued that the Western criticism of palamism presupposes specifically Western ideas stemming from scholasticism without reflection.

Editions and translations

- Panagiotes K. Chrestou (Ed.): Gregoriou tou Palama Syngrammata . 5 volumes, Thessaloniki 1962–1992 (critical edition; only five of the originally planned six volumes have been published)

- Nicholas Gendle (translator): Gregory Palamas: The Triads . Paulist Press, New York 1983, ISBN 0-8091-2447-5 (English translation of part of the 1973 Triad Edition by Jean Meyendorff)

- Jean Meyendorff (ed.): Grégoire Palamas: Défense des saints hésychastes . 2 volumes, 2nd revised edition, Leuven 1973 (critical edition of the triads with French translation)

- Ettore Perrella (Ed.): Gregorio Palamas: Atto e luce divina. Scritti filosofici e teologici . Bompiani, Milano 2003, ISBN 88-452-9234-7 (first volume of a three-volume complete edition of the works; non-critical edition of the Greek texts with Italian translation)

- Ettore Perrella (Ed.): Gregorio Palamas: Dal sovraessenziale all'essenza. Confutazioni, discussioni, scritti confessionali, documenti dalla prigionia fra i Turchi. Bompiani, Milano 2005, ISBN 88-452-3371-5 (second volume of a three-volume complete edition of the works; non-critical edition of the Greek texts with Italian translation)

- Ettore Perrella (Ed.): Gregorio Palamas: Che cos'è l'ortodossia. Capitoli, scritti ascetici, lettere, omelie. Bompiani, Milano 2006, ISBN 88-452-5668-5 (third volume of a three-volume complete edition of the works with indexes for all three volumes; non-critical edition of the Greek texts with Italian translation)

literature

Overview representations

- Georgi Kapriev: Gregorios Palamas. In: Laurent Cesalli, Gerald Hartung (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of the Middle Ages. Volume 1: Byzantium, Judaism. Schwabe, Basel 2019, ISBN 978-3-7965-2623-7 , pp. 145–154, 274–279

- Erich Trapp : Prosopographisches Lexikon der Palaiologenzeit . 9. Faszikel, Verlag der Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1989, pp. 108–116 (with list of works and detailed bibliography; the chronological information partly deviates from the standard representations)

Investigations

- Georg Günter Blum: Byzantine mysticism. Its practice and theology from the 7th century to the beginning of the Turkocracy, its continuation in modern times . Lit Verlag, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-8258-1525-7 , pp. 355-429

- Reinhard Flogaus: Theosis in Palamas and Luther. A contribution to the ecumenical conversation (= research on systematic and ecumenical theology , volume 78). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1997

- Jacques Lison: L'Esprit répandu. La pneumatologie de Grégoire Palamas . Les Éditions du Cerf, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-204-04936-0

- John Meyendorff : A Study of Gregory Palamas . 2nd edition, The Faith Press, Leighton Buzzard 1974

- Gerhard Podskalsky : Theology and Philosophy in Byzantium . Beck, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-406-00415-6

- Kyriakos Savvidis: The doctrine of the deification of man by Maximos the Confessor and its reception by Gregor Palamas . St. Ottilien 1997, ISBN 978-3-88096-139-5

- Günter Weiss: Joannes Kantakuzenos - aristocrat, statesman, emperor and monk - in the development of society in Byzantium in the 14th century . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1969

- Dorothea Wendebourg: Spirit or Energies. On the question of the divine anchoring of Christian life in Byzantine theology (= Munich monographs on historical and systematic theology , Volume 4). Kaiser, Munich 1980

Reception history

- Michael Kunzler: Sources of Grace. Symeon of Thessaloniki († 1429) as an example of the influence of Palamism on orthodox sacramental theology and liturgy . Paulinus-Verlag, Trier 1989, ISBN 3-7902-1275-X

Web links

- Literature by and about Gregorios Palamas in the catalog of the German National Library

- Roman Bannack: Saint Gregorios Palamas and the Byzantine hesychasm

- Jürgen Kuhlmann: Deification in the Holy Spirit. The message of the Athos monk Gregorios Palamas

- Works (Greek; Microsoft Word file in a ZIP archive; 232 kB)

Remarks

- ^ John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, pp. 30 f.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Beck: History of the Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire , Göttingen 1980, p. 221.

- ^ Günter Weiss: Joannes Kantakuzenos - aristocrat, statesman, emperor and monk - in the social development of Byzantium in the 14th century , Wiesbaden 1969, p. 106 f .; John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd Edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, pp. 50-59.

- ↑ On the different party affiliations see Günter Weiss: Joannes Kantakuzenos - aristocrat, statesman, emperor and monk - in the social development of Byzantium in the 14th century , Wiesbaden 1969, pp. 113-134.

- ^ Synodicon of Orthodoxy (German translation) pp. 13-18.

- ↑ For the background to the final decision in favor of Palamism see Hans-Georg Beck: Geschichte der orthodoxen Kirche im Byzantinischen Reich , Göttingen 1980, p. 223 f.

- ^ John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, pp. 104 f.

- ^ John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, pp. 116 f., 126 f.

- ^ John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, pp. 128-131; Gerhard Podskalsky: Theology and Philosophy in Byzanz , Munich 1977, p. 153.

- ^ John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, p. 131.

- ↑ Michael Kunzler: sources of grace. Symeon of Thessaloniki († 1429) as an example of the influence of palamism on orthodox sacramental theology and liturgy , Trier 1989, pp. 7–9; Susanne Hausammann: The life-creating light of indissoluble darkness , Neukirchen-Vluyn 2011, p. 245.

- ↑ Michael Kunzler: sources of grace. Symeon of Thessaloniki († 1429) as an example of the influence of palamism on orthodox sacramental theology and liturgy , Trier 1989, pp. 11-16.

- ^ Günter Weiss: Joannes Kantakuzenos - aristocrat, statesman, emperor and monk - in the social development of Byzantium in the 14th century , Wiesbaden 1969, p. 134 f .; Gerhard Podskalsky: Theology and Philosophy in Byzanz , Munich 1977, p. 154.

- ↑ Michael Kunzler: sources of grace. Symeon of Thessaloniki († 1429) as an example of the influence of palamism on orthodox sacramental theology and liturgy , Trier 1989, p. 15.

- ↑ Susanne Hausammann: The life-creating light of indissoluble darkness , Neukirchen-Vluyn 2011, pp. 248-252.

- ↑ Michael Kunzler: sources of grace. Symeon of Thessaloniki († 1429) as an example of the influence of palamism on orthodox sacramental theology and liturgy , Trier 1989, p. 16; John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, pp. 213 f .; Gerhard Podskalsky: Theology and Philosophy in Byzanz , Munich 1977, p. 154.

- ^ John Meyendorff: A Study of Gregory Palamas , 2nd edition, Leighton Buzzard 1974, p. 225.

- ↑ An overview of the individual Palamitic and anti-Palamitic theologians of the 14th century and their positions is provided by Hans-Georg Beck: Church and theological literature in the Byzantine Empire , 2nd edition, Munich 1977, pp. 716–742.

- ^ Günter Weiss: Joannes Kantakuzenos - aristocrat, statesman, emperor and monk - in the social development of Byzantium in the 14th century , Wiesbaden 1969, p. 137.

- ↑ See Jürgen Kuhlmann: Die Taten des Simple Gottes , Würzburg 1968, pp. 108–125 ( online ).

- ↑ See on this development Michael Kunzler: Gnadenquellen. Symeon of Thessaloniki († 1429) as an example of the influence of palamism on orthodox sacramental theology and liturgy , Trier 1989, pp. 45, 48–51. On the reception in the Russian Orthodox Church, where neo-Palamism met resistance, see Bernhard Schultze: The meaning of palamism in contemporary Russian theology , in: Scholastik 36, 1951, pp. 390-412.

- ↑ Mykola Krokosh: The new Catechism of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church from an ecumenical perspective. In: Der christliche Osten , vol. 67, 2012, pp. 163–170, here: 167.

- ↑ Michael Kunzler: sources of grace. Symeon of Thessaloniki († 1429) as an example of the influence of palamism on orthodox sacramental theology and liturgy , Trier 1989, pp. 52–94, 380 ff., 453.

- ↑ Several contributions to this debate appeared in Eastern Churches Review 9 (1977); the Anglican Rowan D. Williams ( The Philosophical Structures of Palamism , pp. 27–44) and the Catholic Illtyd Trethowan ( Irrationality in Theology and the Palamite Distinction , pp. 19–26) criticize aspects of Palamism, and from an orthodox point of view, Callistus replies Ware ( The Debate about Palamism , pp. 45-63).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gregorios Palamas |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gregory Palamas; Γρηγόριος Παλαμάς |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Byzantine Orthodox theologian and saint |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1296 or 1297 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Constantinople |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 14, 1359 |

| Place of death | Thessalonike |