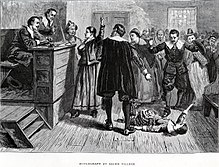

Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials (Salem witch trials) in 1692 were the beginning of a series of arrests, prosecutions and executions for witchcraft in New England . The witch hunt began in the Village Salem (today mostly part of Danvers ), near the city of Salem . In its course, 20 suspects were executed, 55 people tortured to give false testimony, 150 suspects were detained, and another 200 people were charged with witchcraft. The allegations spread to the surrounding communities of Andover, Amesbury, Salisbury, Haverhill, Topsfield, Ipswich, Rowley, Gloucester, Manchester, Malden, Charlestown, Billerica, Beverly, Reading, Woburn, Lynn, Marblehead and Boston within a few months. Until then, witch hunts had only occurred sporadically in the North American colonies, unlike in Europe.

Prehistory of the witch hunt in New England

Historian Clarence F. Jewett compiled a list of victims of the witch hunt in New England prior to 1692 in his book The Memorial History of Boston: Including Suffolk County, Massachusetts 1630–1880 (Ticknor and Company, 1881).

1647 Alice Young, in Hartford, Connecticut - 1648 Margaret Jones , from Charlestown, Massachusetts , in Boston - 1648 Mary Johnson, in Hartford - 1650? Wife of Henry Lake, from Dorchester, Massachusetts - 1650? Mrs. Kendall, of Cambridge, Massachusetts - 1651 Mary Parsons, of Springfield, Massachusetts , in Boston - 1651 Goodwife Bassett, of Fairfield, Connecticut (Goodwife was a polite form of address for women of a lower social rank than a mistress) - 1653 Goodwife Knap in Hartford - 1656 Ann Hibbins in Boston - 1662 Goodman Greensmith in Hartford (Goodman was a polite form of address for men of a lower social rank than Mister) - 1662 Goodwife Greensmith in Hartford

- 1688 Ann Glover (Goody Glover, Goody was an abbreviation of Goodwife) in Boston "

The incidents

In 1689, the revival preacher Samuel Parris was appointed first independent leader of the strictly Puritan congregation of Salem. The focus of his sermons was on the battle between God's chosen people and Satan. In the winter of 1691/92 Elizabeth "Betty" Parris and Abigail Williams , his daughter and niece, began to behave conspicuously, in particular to speak strangely, to hide under things and to crawl on the ground. None of the doctors appointed could explain the girls' suffering medically. The doctor William Griggs suspected after a thorough examination and the ruling out of all mental disorders known at the time that they might be possessed by the devil. The girls seemed to be twisted by the invisible hand of the devil. Abigail and Elisabeth confirmed this by describing how they were tormented by invisible hands. Parris took up this explanation immediately and said that the city had been occupied by Satan. An army of little devils are ready to invade the new settlement. Elizabeth reported that Satan had tried to approach her. Since she had rejected him, he now sends his henchmen, the witches. One means of staving off Satan's attack was to identify and name the witches. In addition to the two girls Betty and Abigail, Ann Putnam , Betty Hubbard, Mercy Lewis, Susannah Sheldon, Mercy Short and Mary Warren were also pressured to name the names of people who had bewitched the girls.

They initially blamed Sarah Good, Sarah Osborne and Tituba. Sarah Good was a well-known beggar woman, daughter of a French innkeeper; she was said to have talked to herself frequently. Sarah Osborne was a bedridden elderly woman believed to have robbed her first husband's children of their inheritance by giving it to their new husband. Tituba was an Indian or black slave of the clergyman Samuel Parris. This reported on witch meetings and claimed to have seen some names in the book of Satan.

The village community, threatened by indigenous tribes and without a formal government after the repeal of the Bay Colony Treaty of 1684 and the uprising of 1689, believed the allegations.

The broad-based Satanism in the allegations differs significantly from the other witch hunts in the country. Influential clergy in New England were well acquainted with the witch trials and trials of children from the Swedish witch trials of the 1660s and 1670s, so the motif of the Devil's Pact and the witches' meetings may have come from Scandinavia.

Course of the processes

On March 1, 1692, the women accused were imprisoned. Charges followed against other people: Dorcas Good, Sarah Good's four-year-old daughter, Rebecca Nurse , a bedridden religious grandmother, Abigail Hobbs, Deliverance Hobbs, Martha Corey, and Elizabeth and John Proctor. Without a government, however, no legal proceedings could be opened. Sarah Osborne and Sarah Good's newborn child died while in custody, and other inmates became ill. Towards the end of May, the Governor Sir William Phips, appointed by the English king, came to Salem to hold a hearing (English "Oyer and Terminer").

The court tried new cases about once a month. All but one of the suspects were sentenced to death for witchcraft. Those convicted who pleaded guilty and named other suspects were not executed. Because of their pregnancy, the execution of Elizabeth Proctor and Abigail Faulkner was postponed. In four executions during the summer, 19 people were hanged, including a clergyman, a gendarme who refused to arrest others suspected of witchcraft, and at least three other prominent figures. Six of those executed were men, the others mostly impoverished older women.

The eighty-year-old farmer Giles Corey refused to testify and was therefore not hanged, but rather executed by crushing with stones on September 19, 1692 .

During the witch trials in Salem, the harvest was not brought in and cattle were neglected. Sawmills stood still because either the owners were missing, their workers were arrested, or they were visiting prisons and trials. Some of the accused fled. Trade almost stalled while the Indian threat remained in the west.

On September 22, 1692, the last eight people were hung, including Martha Corey and five other women.

Under the leadership of Increase Mather , Boston clergy filed an appeal on October 3, 1692, entitled "Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits." In it, Mather stated that it was better for ten suspected witches to escape than for one innocent person to be convicted. The witch trials ended in January 1693. In the spring of the following year, the last of those arrested were released.

Reasons for the witch hunt in Salem

The English, who settled in Salem from 1628, wanted to build the New Jerusalem there as God's chosen people . It should be a theocracy with the Bible, especially the Mosaic Laws, as the code of law. Witchcraft was a death-worthy crime, which the Puritans enshrined in their 1641 and 1648 legislation. They were thus in the tradition of legislation in their country of origin. The law referred directly to 2 Mos 22.17 EU , where the killing of witches is ordered. Half the village consisted of farmers who supported the clergyman Samuel Parris in his endeavors to break away from the city of Salem and to form an independent community. The other half of the villagers wanted to remain part of the township and maintain trade ties and refused to provide financial support to the clergyman and his family. In addition, a number of people who had fled Maine and New Hampshire from Indian attacks had found shelter in Salem with relatives and brought horror stories with them. As a result, Salem was a powder keg in 1691, and the row of seemingly possessed young girls was the spark that detonated it.

There are various theories about the reasons for the sudden witch hunt in Salem. The most common is that the Puritans who have ruled the Massachusetts Bay Colony since 1630 with little royal interference have developed a religiously shaped, mass hysterical delusion. Today's experts consider this representation to be overly simplified. Other theories include child abuse , divination, and misguided experimentation.

Grain contaminated with ergot and the resulting cases of ergotism with delusions were also suspected to be the cause. Another possibility is an intrigue by the Putnam family against the Porter family.

There was also great tension within Puritan society. It had lost its founding treaty in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and faced an uncertain future. The settlers were exposed to constant attacks by Indians and could not hope for English help. The defenders had to be drawn from among their young men, and the Indian revolt in 1675, known as the “King Philips War” , had decimated the population. One in ten New England settlers was killed in Indian attacks. Although this war was over, Indian attacks remained a constant threat. New England became more and more a trading colony. From a sociological point of view, it was a violent protest by the pietistic rural population, clinging to the traditional god-fearing lifestyle, against the new merchant class, which was more open to the world and earned well. The canon of values between these groups was also very different. The girls who portrayed Satan's attacks were members of the rural population and often accused women from the well-off commercial class.

Carol Karlsen examined the connection between the persecution of witches and the position of women. She emphasized that at that time in New England many women were independently defending their inherited assets in court. She believes that a large number of such independent women have been provocative in a strictly patriarchal environment.

Mary Beth Norton ("In the Devil's Snare") argues that probably several or all of the points mentioned played an important role. Salem and the rest of New England were threatened by frequent Indian attacks, which caused fear and therefore greatly contributed to the hysteria. She suspects that most of the witches and girls involved had close social or personal ties with the victims of the Indian attacks of the past 15 years. Prosecutors often mentioned a "black man", discussed witches' meetings with Indians, and described torture images from stories of kidnappings by Indians. Furthermore, the Puritan clergy had maintained since the "King Philips War" that the Indians were associated with the devil and witchcraft. In glowing sermons lasting up to five hours, they portrayed the American Puritans as an army of God that is besieged by Satan and his demons. In summary, it can be said that the Puritans associated Indians with the devil. Indian attacks they saw as attempts of the devil to destroy the Puritan society. With all these influences, the Puritans were ripe for witch hysteria in 1691.

Rehabilitation of victims

A general amnesty was pronounced in 1711 for most of those convicted of the Salem witch trials. In 1957, Ann Pudeator, hanged as a witch, was declared innocent. On November 5, 2001, the Massachusetts governor signed the declaration of innocence for the last five women.

Literary adaptations of the topic

- Arthur Miller used the witch trials as an analogy to the communist persecution of the McCarthy era in his 1953 play The Crucible .

- Nathaniel Hawthorne referred to the trials in various works, including Young Goodman Brown .

- HP Lovecraft used Salem as a model for the city of Arkham , a setting in his horror stories.

- Wolfgang Hohlbein wrote a series of books entitled The Witcher of Salem , in which the subject is mixed with HP Lovecraft's Cthulhu myth .

- Andrzej Sapkowski was inspired by the trials for the short story An Incident in Mischief Creek in his anthology Something Ends, Something Begins .

Film adaptations

In 1937, the Paramount production appeared in cross-examination (original title: Maid of Salem ). Directed by Frank Lloyd , in the lead roles were Claudette Colbert , Fred MacMurray and Gale Sondergaard to see. The film tells a fictional story about a young woman accused of witchcraft against the background of the historical witch trials.

In 1957, the filmed DEFA in French - German co-production which is based on the processes play by Arthur Miller , entitled The Witches of Salem (also known under the title witch hunt ). Contributors included Yves Montand , Simone Signoret , Michel Piccoli and Sabine Thalbach , the script was written by Jean-Paul Sartre , the music was by Hanns Eisler .

In 1960, a German TV adaptation of Miller's play appeared. Directed by Ludwig Cremer , Hans Christian Blech played the leading role .

In 1972, The Witches of Salem: The Horror and the Hope by Dennis Azzarella was filmed in the USA . The half-hour short film was intended for school lessons and strives for historical accuracy, the dialogues are based on the original trial files.

In 1996 the topic was filmed again under the title witch hunt (English original title: The Crucible ). Miller wrote the script himself. a. Daniel Day-Lewis as John Proctor , Winona Ryder as Abigail Williams , Paul Scofield as Judge Thomas Danforth , Joan Allen as Elizabeth Proctor and Bruce Davison as Reverend Samuel Parris . The film was nominated for two Academy Awards.

The US television series Salem - consisting of 3 seasons that could be seen from April 2014 to January 2017 - is based in part on actual events and real people, e.g. B. Cotton and Increase Mathers, Tituba and Mercy Lewis; For dramaturgical reasons, however, fictional, primarily supernatural, elements and people were included that deviate from the historical facts.

In addition to these films, which deal with the historical events in Salem, the witch trials occasionally also serve as a background for horror films set in the present . Often it is about descendants of people involved in the processes at the time. In contrast to historical reality, the accused at the time are mostly actually ascribed magical powers and assumed to be involved in occult rituals.

In the 1980 film A Zombie Hung on the Bell Rope by Lucio Fulci , the city of Dunwich , borrowed from HP Lovecraft and where evil breaks out, is built on the ruins of the city of Salem, where the showdown also takes place.

In 2006, the film The Covenant was released by Renny Harlin . The main roles included Steven Strait , Laura Ramsey and Taylor Kitsch .

The US television series American Horror Story deals with the 2014 Salem witch trials in its third season.

In 2012 Rob Zombie's horror film " The Lords of Salem " was released.

In André Øvredal's horror film The Autopsy of Jane Doe from 2016, some evidence is raised that the examined corpse is a suspected witch from the Salem witch trials.

The horror computer game Murdered: Soul Suspect is set in Salem and refers to the witch trials.

Involved

Executed

- Bridget Bishop - hanged June 10, 1692

- Rev. George Burroughs - hanged August 19, 1692

- Martha Carrier - hanged August 19, 1692

- Martha Corey - hanged September 22, 1692

- Giles Corey - bruised to death September 19, 1692

- Mary Easty - hanged September 22, 1692

- Sarah Good - hanged July 19, 1692

- Elizabeth Howe - hanged June 19, 1692

- George Jacobs, Sr. - hanged August 19, 1692

- Susannah Martin - hanged June 19, 1692

- Rebecca Nurse - hanged June 19, 1692

- Alice Parker - hanged September 22, 1692

- Mary Parker - hanged September 22, 1692

- John Proctor - hanged August 19, 1692

- Ann Pudeator - hanged September 22, 1692

- Wilmott Redd - hanged September 22, 1692

- Margaret Scott - hanged September 22, 1692

- Samuel Wardwell - hanged September 22, 1692

- Sarah Wildes - hanged June 19, 1692

- John Willard - hanged August 19, 1692

Died in custody

- Sarah Osborne

- Roger Toothaker

- Ann Foster

- Lydia Dustin

- Newborn daughter of Sarah Good

Affected

- Sarah Bibber

- Elizabeth Booth

- Sarah Churchill (charged with witchcraft when she testified that the accusers were making up her allegations)

- Martha Goodwin

- Elizabeth Hubbard

- Mary Lacey

- Mercy Lewis

- Elizabeth Parris

- Bethshaa Pope

- Ann Putnam, Jr.

- Susanna Sheldon

- Mercy Short

- Martha Sprague

- Mary Walcott

- Mary Warren (charged with witchcraft after testifying the allegations were fabricated)

- Abigail Williams

accused

The list is not exhaustive, between 150 and 300 were charged, and significantly more may have been detained:

- John Alden Jr.

- Daniel Andrew

- Sarah Bassett

- Edward Bishop

- Sarah Bishop

- Mary Black

- Dudley Bradstreet

- John Bradstreet

- Sarah Buckley

- Candy, a slave from Salem

- Richard Carrier

- Mary Clarke

- Sarah Easty Cloyce

- Sarah Cole

- Giles Corey , died under torture

- Mary Bassett DeRich

- Ann Dolliver

- Rebecca Eames

- Mary English

- Philip English

- Abigail Faulkner

- Ann Foster

- Dorcas Good

- Dorcas Hoar

- Abigail Hobbs

- Deliverance Hobbs

- Elizabeth Howe

- Mary Ireson

- George Jacobs, Jr.

- Margaret Jacobs

- Elizabeth Johnson

- Mary Lacey, Sr.

- Mary Lacey

- Sarah Osborne

- Lady Phips, wife of Governor Phips

- Susannah Post

- Elizabeth Bassett Proctor

- Tituba

- Job Tookey

- Hezekiah Usher

- Mary Withridge

Spiritual participants and commentators

- Rev. Cotton Mather

- Rev. Samuel Parris

- Rev. Increase Mather

- Rev. Francis Dane

- Rev. Deodat Lawson

- Rev. Samuel Willard

- Rev. John Hale

- Rev. John Wise (Pastor)

Chair in the proceedings

- Deputy Governor (lieutenant governor) William Stoughton , Presiding Judge

Investigating magistrates involved

- John Hathorne

- Samuel Sewall

- Thomas Danforth

- Bartholomew Gedney

- John Richards

- Nathaniel Saltonstall

- Peter Sargent

- Stephen Sewall, Clerk

- Wait Still Winthrop

literature

- Marc Aronson: Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials. Simon and Schuster, November 2003, hardcover, 272 pages, ISBN 0-689-84864-1 ; Large-print, Thorndike Press, April 2004, hardcover, 324 pages, ISBN 0-7862-6442-X .

- Emerson W. Baker: A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience. Oxford University Press, New York 2014, ISBN 978-0-19-989034-7 .

- Paul Boyer, Stephen Nissenbaum: Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft. MJF Books 1974.

- Linnda Caporeal's article Ergotism: The Satan Loosed in Salem?

- Tony Fels: Switching Sides: How a Generation of Historians Lost Sympathy for the Victims of the Salem Witch Hunt. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2018, ISBN 978-1-4214-2437-8 .

- Peter Charles Hoffer: The Salem Witchcraft Trials: A Legal History. University Press of Kansas, Lawrence 1997, ISBN 978-0-7006-0859-1 .

- Mary Beth Norton: In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. Knopf 2002.

- Benjamin C. Ray: Satan and Salem: The Witch-Hunt Crisis of 1692. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville 2015, ISBN 978-0-8139-3707-6 .

- Elizabeth Reis: Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY 1997.

- Marilynne K. Roach: The Salem Witch Trials: A Day-To-Day Chronicle of a Community Under Siege. Cooper Square Press 2002.

- Marilynne K. Roach: Six Women of Salem: The Untold Story of the Accused and Their Accusers in the Salem Witch Trials. Da Capo Press, Boston 2012, ISBN 978-0-306-82120-2 .

- Bernard Rosenthal: Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2013, ISBN 978-1-107-68961-9 .

- Stacy Schiff : The Witches: Salem, 1692 . Little, Brown and Company, New York 2015.

- Marion L. Starkey: The Devil in Massachusetts. Alfred A. Knopf 1949.

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ John Clarke Ridpath: History of the World . 1923

- ^ Clarence F. Jewett, The Memorial History of Boston: Including Suffolk County, Massachusetts. 1630-1880 ( Ticknor and Company , 1881) pages 133-137

- ↑ Hagen p. 72.

- ↑ Elaine G Breslaw: Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies . New York, University Press, 1996

- ^ Veta Smith Tucker: Purloined Identity: The Racial Metamorphosis of Tituba of Salem Village . Journal of Black Studies, March 2000

- ↑ Hagen p. 73.

- ↑ American Weekly: Poor Old “Goody” Cole Cleansed of Witchcraft After 300 Years . 1938

- ^ Dominik Nagl: No Part of the Mother Country, But Distinct Dominions. Legal transfer, state formation and governance in England, Massachusetts and South Carolina, 1630 - 1769. LIT Verlag, Berlin 2013, pp. 224–234, 508. online

- ↑ Hagen p. 74.

- ↑ Convulsive ergotism may have been a physiological basis for the Salem witchcraft crisis in 1692. ( Memento of May 11, 2008 in the Internet Archive ) Linnda R. Caporael in Science Vol. 192 (April 2, 1976) (eng.)

- ↑ Hagen p. 76.

- ^ The devil in the Shape of woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England. New York 1978, 1998.

- ↑ Chapter 145 of the Resolves of 1957, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts; Chapter 122 of the Acts of 2001, Commonwealth of Massachusetts (see http://www.mass.gov/legis/laws/seslaw01/sl010122.htm ); “New Law Exonerates,” Boston Globe, Nov. 1, 2001