Jewish culture in Islamic al-Andalus

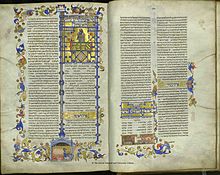

The Jewish Culture experienced in al-Andalus , the Muslim dominated from 711 to 1492 part of the Iberian Peninsula , a period of cultural and economic prosperity. Al-Andalus became a center of Jewish life in the European Middle Ages , when one of the most stable and prosperous Jewish societies of its time developed. A number of eminent Jewish scholars emerged from this society.

historical overview

As in other regions during the Islamic expansion , the new Muslim rulers, after conquering large parts of the Iberian Peninsula, faced the task of consolidating their rule over a still largely non-Islamic population and the coexistence of Muslims, Jews and Christians according to the Islamic one Right to shape. Times of relative tolerance alternated with those of greater oppression. The beginning of the "Golden Age" is therefore either with the conquest by the Umayyads 711-18 or the beginning of the rule of Abd ar-Rahman III. Dated 912, its end equated with the end of the Caliphate of Córdoba in 1031, the massacre of Granada in 1066, the invasion of the Almoravids in 1090 or the Almohads in the middle of the 12th century. 'Abd al-Rahman's personal physician and court official was Hasdai ibn Shaprut , the teacher of Menachem ben Saruq and Dunasch ben Labrat . The Jewish scholars of this time include Shmuel ha-Nagid , Moses ibn Esra , Solomon ibn Gabirol , and Jehuda ha-Levi . During his reign, Moshe ben Hanoch was appointed rabbi of Córdoba. In the following period the city became a center of Talmudic studies and a meeting place for Jewish scholars.

With the death of Al-Hakam (II.) Ibn Abd-ar-Rahman in 976, the caliphate was in the process of dissolution, and the position of the Jews in the successor states, the Taifa kingdoms , became more critical. A first major pogrom took place in Granada in 1066 . On December 30th of that year, a crowd of Muslims stormed the Caliph's Palace and murdered a large part of the city's Jewish population. The Jewish vizier Joseph ibn Naghrela was crucified. More than 1,500 Jewish families, around 4,000 people, were murdered.

After 1090, the situation of the Jews worsened when the strict Islamic Berber dynasty of the Almoravids occupied al-Andalus from Morocco . Nevertheless, some Jews managed to maintain their position under the Almoravid rulers Yusuf ibn Tashfin and his son Ali III. to assert: The doctor and poet Abu Ayyub Solomon ibn al-Mu'allam , as well as Abraham ibn Meir ibn Kamnial , Abu Isaac ibn Muhajar and Solomon ibn Farusal served as viziers ( Hebrew Nasi ). In 1148 the Almoravids were ousted by the even more devout Almohads . Under their rule, many Jews and even Muslims left the Islamic ruled areas of al-Andalus, some found refuge in 1085 from Alfonso VI. of León conquered Toledo .

The famous Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides (1135–1204) was forced to flee al-Andalus in order to escape his forced conversion. He wrote in his " Letter to Yemen ":

“Dear brothers, because of our many sins, the Most High has thrown us among this people, the Arabs, who treat us badly. They legislate for the purpose of oppressing us and making us despicable. [...] There has never been a people who hated, humiliated and despised us so much as this one. "

After the Reconquista , in the Alhambra Edict of March 31, 1492 , the Catholic Kings ordered the expulsion of the Jews from Castile and Aragon on July 31, 1492, provided they had not converted to Christianity by then . Afterwards, many Sephardic Jews emigrated from Spain, and after 1496/97 also from Portugal, and found refuge in the Ottoman Empire, where they were welcomed by a decree of Sultan Bayezids II .

Jewish life in al-Andalus

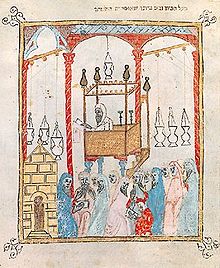

The Jewish population of the Iberian Peninsula grew rapidly through immigration from the Islamically conquered areas of North Africa in the course of the 8th century. The reign of Abd ar-Rahman III. from 912 and his son Al-Hakam II marked a period of greater tolerance. In the Caliphate of Córdoba significant works were Jewish philosophers , mathematicians, astronomers, poets and rabbinical scholar. The Jewish population in particular achieved prosperity through science, trade and commerce. Jewish merchants ( Radhanites ) brokered trade between Christian Europe and the Islamic world and achieved prosperity.

As “ dhimmi ”, “worthy of protection”, Jews in the Islamic world were obliged to pay poll tax ( jizya ) . Jews had their own jurisdiction and social support systems. Members of monotheistic scriptural religions were tolerated, and in most cases they were not allowed to practice their faith in public. Compared to the Christian countries, Jews in the medieval Islamic world were better integrated into political and economic life, and were also less exposed to violence over longer periods of time.

Great personalities

Other important Jewish personalities from al-Andalus were:

- Abu al-Fadl ibn Hasda, philosopher and vizier in Saragossa

- Abu Ruiz ibn Dahri fought in the war against the Almohads .

- Bachja ibn Pakuda , philosopher and author of Pijjutim ; Major work Kitāb al-Hidāya ilā Farā'iḍ al-Qulūb , translated into Hebrew in 1161 by Jehuda ibn Tibbon under the title Chowot ha-Lewawot ("Duties of the Heart").

- Bishop Bodo (Eleazar), Frankish deacon at the court of Louis the Pious , converted to the Jewish faith in Cordoba in 838.

- Dunasch ben Labrat (920–990), poet

- Isaac ibn Albalia, astronomer and rabbi in Granada

- Jekuthiel ibn Hasan, Minister in Saragossa

- Joseph ibn Hasdai, poet, father of Abu l-Fadl ibn Hasdai

- Josef ibn Migasch , successor of Isaak Alfasis as rabbi in Lucena

- Maimonides , rabbi, doctor and philosopher

- Menachem ben Saruq

- Nachmanides

- Solomon ibn Gabirol , poet and philosopher

- Moses ben Hanoch

- Yehuda ha-Levi , poet and philosopher

- Abraham ibn Esra , rabbi and poet

- Moses ibn Esra , poet and philosopher

- Benjamin von Tudela , explorer

- Shmuel ha-Nagid , vizier and poet

- Hasdai ibn Schaprut , personal physician and diplomat

- Yehuda ibn Tibbon , translator

Today's assessment

The structure of society in al-Andalus is controversial with regard to its religious tolerance. Mendoza describes tolerance as "inherent in Al-Andalusian society". Menocal argues that the status of “wards” ( dhimma ) granted to members of the scriptural religions in Islamic law granted Jews under Islamic rule more freedom than they would have enjoyed in European Christian societies. As a result, Jews from other regions immigrated to places where they were not only tolerated, but were able to enjoy extensive religious and economic freedoms, with the exception of the ban on proselytizing. Lewis disagrees with this view as being unhistorical and exaggerated. He writes that the idea of the equality of creeds means "a both theological and logical absurdity". He executes:

“In general, Jews were allowed to lead their religion and their lives according to the laws of their community. Furthermore, the constraints they were subjected to were social and symbolic in nature rather than tangible and practical. The rules served, so to speak, to define the relationship between the two communities, not so much to oppress the Jews. "

The American historian David Nirenberg criticizes the idea of "convivencia", the peaceful coexistence of religions, and describes that "violence was a central and systematic aspect of the coexistence of majority and minority in medieval Spain". The Spanish medieval researcher Eduardo Manzano Moreno wrote that the concept of “convivencia” cannot be derived from the sources (“el concepto de convivencia no tiene ninguna apoyatura histórica”). There are hardly any sources known from the time of the Caliphate of Córdoba that dealt with the coexistence of Jews and Christians, which "in view of the enormous weight of the topos of the Convivencia could be shocking for some" ("[...] quizá pueda resultar chocante teniendo en cuenta el enorme peso del tópico convivencial. ”) Manzano traces the origin of this myth back to the Spanish philologist Américo Castro (1885–1972), since he was unable to substantiate his claims from contemporary sources. In 2006 Darío Fernández-Morera also criticized the modern understanding of al-Andalus as a tolerant society with extensive equal opportunities for members of all religions. Jews, Muslims and Christians lived together in unrest, which was more characterized by demarcation and mutual hostility. During the massacre in Granada the number of Jewish deaths was far higher than in the later persecution of Jews in the Rhineland. Mark R. Cohen called the “idealized interreligious utopia” a “myth”, which was first brought up by Jewish historians like Heinrich Graetz in the 19th century was to criticize Christian societies. This myth is encountered by the “counter-legend” of a “neo-maudlin Jewish-Arab story” by the author Bat Yeʾor and others, which “cannot be sustained in the light of historical reality”.

Web links

- Article “Spain” in the Jewish Encyclopedia , accessed June 12, 2016.

- Article “Sephardim” in the Jewish Virtual Library , accessed June 12, 2016.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Article “Sephardim” by Rebecca Weiner, Jewish Virtual Library, accessed on June 13, 2016.

- ^ Article "Granada" by Richard Gottheil , Meyer Kayserling , Jewish Encyclopedia , 1906, accessed June 13, 2016

- ↑ Avraham Yaakov Finkel (English excerpt.): Rambam: Selected Letters of Maimonides . Yeshivat Beth Moshe, Scranton, PA 1994, ISBN 978-0-9626226-3-2 , pp. 58 .

- ↑ Asunción Blasco Martínez: La expulsión de los judíos de España en 1492 . In: Kalakorikos: Revista para el estudio, defensa, protección y divulgación del patrimonio histórico, artístico y cultural de Calahorra y su entorno . No. 10 , 2005, pp. 13 f . (Spanish, unirioja.es [accessed June 11, 2016]).

- ^ Ilan Stavans : The Scroll and the Cross: 1,000 Years of Jewish-Hispanic Literature . Routledge, London 2003, ISBN 978-0-415-92931-8 , pp. 10 .

- ^ Michael McCormick: Origins of the European Economy. Communications and Commerce AD 300-900 . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 2001, ISBN 978-0-521-66102-7 .

- ↑ Fred J. Hill et al., A History of the Islamic World 2003 ISBN 0-7818-1015-9 , p. 73

- ^ Mark R. Cohen: Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages . Princeton University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-691-13931-9 , pp. 66–67, 88 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Mark R. Cohen: Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages . Princeton University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-691-13931-9 , pp. xvii, xix, 22, 163, 169 .

- ↑ Allen Cabaniss: Bodo-Elezazar: A Famous Jewish Convert . In: Institute for Advanced Study (Ed.): IAS – The Institute Letter . 43, September, pp. 313-328.

- ↑ María Rosa Menocal: "The Ornament of the World" ( Memento of August 28, 2005 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on June 13, 2016

- ^ A b Bernard W. Lewis: The Jews of Islam . Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ 2014, ISBN 978-1-4008-2029-0 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ^ David Nirenberg: Communities of violence - Persecution of Minorities in the Middle ages . Princeton University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-691-03375-4 , pp. 9 .

- ↑ Eduardo Manzano Moreno: Qurtuba: Algunas reflexiones críticas sobre el califato de Córdoba y el mito de la convivencia [Qurtuba: Critical reflections on the Caliphate of Cordoba and the myth of the convivencia]. In: Awraq n. ° 7. 2013, pp. 225–246 ( Online , PDF, 179 KB, accessed on June 13, 2016)

- ↑ Darío Fernández-Morera (2006): The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise. The Intercollegiate Review , Autumn 2006, pp. 23–31, here p. 25 online (PDF) , accessed on June 13, 2016.

- ^ Mark R. Cohen: Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages . Princeton University Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-691-13931-9 .

- ^ Daniel J. Lasker: Review of Under Crescent and Cross. The Jews in the Middle Ages by Mark R. Cohen . In: The Jewish Quarterly Review . 88, No. 1/2, 1997, pp. 76-78. doi : 10.2307 / 1455066 .