History of the Jews in Spain

The history of Jews in Spain ( Sephardim or Sephardic Jews according to the Hebrew name for Spain סְפָרַד Sfarád ) dates back more than 2000 years to the time of the Roman Empire. In the Middle Ages, under Islamic and later Christian rule, Jewish life flourished on the Iberian Peninsula , both culturally and economically. This heyday ended in 1492 with the deportation edict ( Alhambra Edict ) of the Catholic kings Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand of Aragon . The Jews were either forced to convert to Christianity or to emigrate from Spain. For centuries afterwards, open Jewish life was no longer possible in Spain until modern times. The Jews expelled from Spain settled in the rest of the Mediterranean region and in part still retained the culture and language they had brought with them from Spain, Jewish Spanish (Spanish, Ladino).

Beginnings of Jewish life in Spain in antiquity and in the Roman Empire

Some authors have already linked Tarsis, mentioned in the Old Testament and the Tanakh , with the Iberian Peninsula. In the 1st Book of Kings ( 1 Kings 10.22 EU ) and in the book of Ezekiel ( Ez 27.12 EU ) trade connections between Jews and Tarsis are described. Ultimately, however, the localization of tarsis is still uncertain. The first secure documents of Jewish settlements on Spanish soil come from Roman times . Even before the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in AD 70 by Titus , Jews lived not only in Palestine, but throughout the Mediterranean. Most of the Iberian Peninsula had been under Roman rule since the Second Punic War (218–202 BC). An increased settlement of Jews in Spain began with the failed uprisings of the Jews against Roman rule (the Jewish War 66 to 74 AD and the Bar Kochba uprising 132 to 135 AD). The announcement of the Apostle Paul in Romans that he wanted to travel to Spain ( Rom 15.24 EU ) is seen by some authors as an indication that there were Jewish communities there. At the early Christian Spanish Synod of Elvira around 300 AD, precise regulations were issued on the dealings between Jews and Christians, which suggests an intense Jewish life in Spain.

Under the Visigothic rule

During the Great Migration in the 4th to 6th centuries AD, the western Roman Empire disintegrated and invading Germanic peoples took possession of the former Roman provinces. From 418 the Visigoths were settled as federates in the Roman province of Aquitaine and Hispania . Just a few years later, the settled Goths became independent and established their own empire in Aquitaine and the northern Iberian peninsula. The Goths were originally Arians and initially paid little attention to the Jewish communities living in their domain. In 587, under Rekkared I , the majority of Visigoths converted from Arianism to Catholicism. In connection with this, the situation of the Jews deteriorated under their rule and in a number of imperial councils in Toledo, chaired by the Visigoth kings, anti-Jewish regulations were repeatedly passed. At the third council of Toledo in 589, Jews were forbidden to assume public office, the contact between Jews and Christians was restricted, and the forced baptism of children from Judeo-Christian intermarriages was sanctioned. However, these regulations could not be consistently enforced. During the reign of King Sisebut (612–621), renewed anti-Jewish activities have been handed down. Sisebut even wanted to enforce a forced conversion of the Jews. In 613 they were given the alternative of either leaving the country or accepting baptism. There were expulsions of Jews who did not want to be converted to Christianity. With the permission of Sisebut's successor, Suinthila , they were allowed to return to their traditional beliefs. At the fourth council of Toledo in 633 it was stipulated that Jews who had only pretended to convert to Christianity but who continued to practice their Jewish religion in secret ("crypto-Judaism") should have their children taken away, who would then be raised in Christian families should. At the 6th Council of Toledo in 638 under King Chintila , all non-Catholics were denied the right to stay in the Visigothic Empire. Anti-Jewish measures were intensified in the second half of the 7th century. King Rekkeswinth forbade circumcision and the observance of the Sabbath and Jewish holidays.

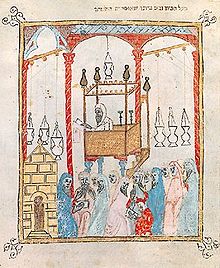

Jewish life under Moorish rule in Spain

With the Islamic conquest of most of the Iberian Peninsula in the years after 711, the situation for the Jews living there changed fundamentally. The new Islamic rulers were relatively tolerant of the Jews and also of the Christians by the standards of the time and allowed both of them to practice their religion. The period of Islamic rule is often referred to as the "Golden Age" for Jewish culture in Spain. Due to the possibilities of the development of Jewish life, there was also an immigration of Jews from outside. Through contact with Arabic scribes and the Arabic literature, Sephardic scholars gained access to the traditional literature of antiquity (writings of Aristotle , etc.). Many Jewish scholars also adopted the Arabic script and language, and some of them rose to high state offices under the Caliphate of Cordoba , such as Chasdai ibn Shaprut (915–970). The contact with Islamic culture also modernized the Hebrew language, which had already ceased as a colloquial language in the 3rd century BC and was only used in the religious field. In Spain, Hebrew was once again open to the world, turned towards this world, a language in which the profane things in life, such as love or the enjoyment of wine, could be sung about by poets. Important Jewish scholars of this time were u. a .:

- Menachem ben Saruq (died around 970, author of the first Hebrew dictionary)

- Dunasch ben Labrat (died 990, poet and grammarian)

- Solomon ibn Gabirol (died around 1057, poet and Neoplatonic philosopher)

- Moses ibn Esra (died around 1138, poet and philosopher)

- Moses Maimonides (born between 1135 and 1138, philosopher, legal scholar and doctor)

Sephardic scholars were also active in the fields of astronomy, medicine, logic, and mathematics.

Jewish life in the Christian kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula until 1492

Large communities emerged in Toledo , Saragossa and Seville . During the Christian Reconquista , the Jewish population in Spain initially continued to grow; The different ethnic groups, never understood as egalitarian, lived in peaceful coexistence ("convivencia"). That changed in the 14th century, when religious, economically and politically motivated hostility towards Jews led to pogroms like the one in Seville in 1391. In the course of the 15th century, more and more Jews converted to Christianity, which led to growing mistrust among the ancient Christians, especially in Castile, because of suspected infiltration. In 1449 there was an organized rebellion against the Conversos in Toledo, which led to the first municipal statute to deny new Christians offices in Toledo, the starting point of the Spanish policy of blood purity . The introduction of the Spanish Inquisition in 1478 is also related to the distrust of Jewish conversos. With the Alhambra Edict of 1492, the Jews were finally expelled from Spain or forced to convert if they wanted to stay. The Ottoman Empire accepted the Jews expelled from Spain and from Portugal from 1580 onwards without any conditions. Bayezid II is said to have said: "How foolish are the Spanish kings that they expel their best citizens and leave them to their worst enemies."

Jewish life in Spain from 1492 to the present

More than 100,000 Spanish Jews made their way into exile in 1492 because of the previously unheard of ethnic cleansing in Spain. Some first went to Portugal, but from there they were also expelled in 1497. Most of them fled to the countries of the Levant, to North Africa, and still others to the North Sea ports of Antwerp and Amsterdam as well as to Hamburg and Italy. The main stream of refugees found a new home in the Ottoman Empire .

But the Balkans were also settled by Jews. A large Sephardic, Ladino-speaking community emerged in Salonika . With the Ottoman conquests, Turkish Jews came to Bulgaria , Belgrade , Budapest and Bosnia . From the first half of the 18th century, Vienna was a popular destination for Jewish immigration. As Turkish citizens, the immigrant Jews enjoyed the right to freedom of movement and religious practice. The Sephardic Congregation was founded in 1735 and in the 19th century had between 5,000 and 6,000 members.

Through the edict of expulsion, the special form of crypto or secret Judaism developed in Spain . Formally Roman Catholic, but secretly Jewish and intermarried, a unique form of Judaism emerged. The external compulsion to keep the religion secret shaped the crypto-Jews even for many generations. Later emigrants from Spain also kept their religion a secret. So lived z. In Austria, for example, there are those crypto-Jews who did not admit their religion until after the Second World War , although according to the Israelitische Kultusgemeinde Wien there are still Sephardim who are officially Roman Catholic to this day. Furthermore, many Spanish crypto Jews emigrated to the Spanish colonies , such as B. to New Spain .

Many converts ( conversos ) were viewed with suspicion by their Spanish Catholic contemporaries and were despised as Marranen or Marranos (literally "pigs"). In order to deny the Conversos and their descendants access to higher offices, racist laws were passed in early modern Spain that provide evidence of " purity of blood " ( limpieza de sangre ), i.e. H. of non-Jewish descent.

It took until the beginning of the 20th century for smaller groups of Jews to settle in Spain again. Especially before and during the Second World War , numerous Jews fled to Spain. It was only through the increase in numbers that many of the crypto-Jews described above declared themselves officially Jewish again. The largest Jewish community is now in Barcelona . Descendants of Sephardim are expressly welcome in Spain today, which is expressed, among other things, in the easing of naturalization.

The synagogue in Madrid , inaugurated in 1968, is the first synagogue built in Spain after the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. Today about 10,000-15,000 Jews live in Spain, which is about 0.03% of the Spanish population.

In 2012 the Spanish government of the time decided to offer the descendants of the Sephardic Jews the granting of Spanish citizenship in return for the expulsion of their ancestors from Spain. As a prerequisite, the old citizenship was initially required. This condition was dropped on June 11, 2015 in a further statutory provision. From October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2019, people of Sephardic descent could apply for Spanish citizenship. Belonging to the Jewish religious community was not a requirement. In total, around 127,000 applications were received during the four-year period mentioned. Most came from Latin America (especially Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia).

literature

- Yitzhak (Fritz) Baer : A History of the Jews in Christian Spain. Volume 1: From the Age of Reconquest to the Fourteenth Century. Vol. 2: From the Fourteenth Century to the Expulsion. Translated from the Hebrew by Louis Schoffman. Philadelphia 1961, ISBN 0-8276-0431-9 .

- Solomon Katz: The Jews in the Visigothic and Frankish Kingdoms of Spain and Gaul. (Monographs of the Mediaeval Academy of America 12). Cambridge, MA 1937.

- Valeriu Marcu : The Expulsion of the Jews from Spain. Querido, Amsterdam 1934, reissued by: Matthes & Seitz, Munich 1991, ISBN 3-88221-795-2 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ WP Bowers: Jewish Communities in Spain in the Time of Paul the Apostle. Journal of Theological Studies, Vol. 26, Part 2 (October 1975), p. 395.

- ↑ Kurt Schubert : Jüdische Geschichte , C. H. Beck, 7th edition, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-44918-5 , p. 64.

- ↑ Kurt Schubert : Jüdische Geschichte , C. H. Beck, 7th edition, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-406-44918-5 , p. 64.

- ^ Georg Bossong: The Moorish Spain , C. H. Beck, 3rd edition, 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-55488-9 , pp. 69 and 70.

- ^ Nuria Corral Sánchez: El pogromo de 1391 en las Crónicas de Pero López de Ayala. In: From Initio: Revista digital para estudiantes de Historia. Vol. 5, 2014, No. 10, pp. 61–75 (PDF) .

- ^ Stafford Poole: The Politics of Limpieza de Sangre: Juan de Ovando and His Circle in the Reign of Philip II. In: The Americas. Vol. 55, 1999, No. 3, pp. 359-389, here p. 361.

- ^ Stafford Poole: The Politics of Limpieza de Sangre: Juan de Ovando and His Circle in the Reign of Philip II. In: The Americas. Vol. 55, 1999, No. 3, pp. 359-389, here p. 362.

- ↑ More and more people of Hispanic origin are discovering their Jewish roots: [1] , Amy Klein, Jüdische Allgemeine, December 3, 2009.

- ↑ Arnold Dashefsky, Ira Sheskin: American Jewish Year Book, 2012. Retrieved on January 4, 2014 (English, ISBN 978-94-007-5204-7 ).

- ↑ Spain passes law of return for Sephardic Jews. Jewish Telegraphic Agency, June 11, 2015, accessed February 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Spain naturalises expelled Sephardic Jews' descendants. BBC News, October 2, 2015, accessed February 13, 2020 .

- ↑ Spain gets 127,000 citizenship applications from Sephardi Jews. October 1, 2019, accessed on February 13, 2020 .