Kildin-Sami language

| Kildinsamisch Кӣллт са̄мь кӣлл | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Spoken in |

Russia | |

| speaker | ≈500 | |

| Linguistic classification |

|

|

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | - | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639 -1 |

- |

|

| ISO 639 -2 |

smi (other Sami) |

|

| ISO 639-3 |

sjd |

|

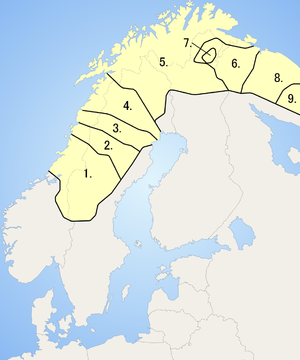

The Kildinsamische language (own name Кӣллт са̄мь кӣлл (Kiillt saam 'kiill)) is a language from the eastern group of the Sami languages and thus belongs to the Urals language family. It is spoken by about 500 Sami on the Kola Peninsula in northwest Russia .

distribution

Kildin Sami is spoken by around 500 people in the central parts of the Kola Peninsula, particularly the Lowosero area . The language takes its name from the island of Kildin northeast of Murmansk . Kildin Sami is the largest language in the group of East Sami languages, but its continued existence is more questionable than that of Inari Sami and Skolt Sami because of the increasing spread of Russian . The languages most closely related to Kildinsami are Tersaami and Akkalasami , which is now probably extinct , and which is sometimes understood as the Kildinsamian dialect.

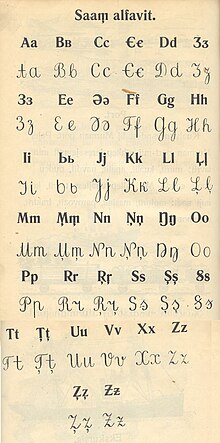

spelling, orthography

In the 1930s, a written Kolasam language based on the Latin alphabet was first developed. This written language was not based on the dialects of Kildin Sami, but on the then largest and geographically central dialect group of the Skoltsami . Due to the Soviet language policy, the Latin alphabet was no longer used after the Second World War , just as linguistic research into Sami in Russia came to a standstill.

In the 1970s, work began again on a written Kolasam language. The Sami teacher Alexandra Antonova wrote a primer in Kildin Sami, Са̄мь букварь, in a new orthography in 1982. The basis was the letters of the Russian alphabet. Special Kildinsamian sounds were created with the help of diacritics (e.g. vowel length ӯ for / u: /) and other modifiers (e.g. the voiceless sonorants ӆ / l̥ /, ӎ / m̥ /, ӊ / n̥ / and ҏ / r̥ / [but not / j̊ /]) is marked. The so-called half-palatalization of / t /, / d / and / n / (marked by the Church Slavonic letter Ҍ ҍ [e.g. -тҍ] or also with diacritics [e.g. -ӭ] was also marked in the script. , depending on the position of the corresponding consonant in the final or before the vowel.)

Antonowa's spelling, which Georgi Kert also used for his Kildinsamisch-Russian-Kildinsamisches school dictionary published in 1986, was further developed by the teacher and linguist Rimma Kurutsch . Kurutsch worked together with Antonova and other Sami employees in Murmansk on the further development of the Kolasam written language. In addition to textbooks and didactic material for teacher training, Kurutsch's group also produced a large Kildin-Sami-Russian dictionary. The dictionary was published in 1985 and contains a short, standardized overview grammar of Kildin Sami. Antonova's spelling was supplemented with the letters Һ һ as a symbol for pre- aspiration and Ј ј for the voiceless palatal approximant / j̊ /.

However, these two letters were later replaced by '(apostrophe) and Ҋ ҋ . This last version of the orthography is fixed in the book on the basics and rules of orthography published in 1995 by the Kurutsch working group. The said rules and the last letters added have never been accepted by all Saami in Russia. This is why all the different versions of the new Cyrillic spelling for Kildin Sami coexist in practice today.

The Saami Cyrillic alphabet contains the following letters:

| А а [ a ] | А̄ а̄ [ a: ] | Ӓ ӓ [ a ] | Б б [ b ] | В в [ v ] | Г г [ g ] |

| Д д [ d ] | Е е [ e ] [ ever ] | Е̄ е̄ [ e: ] [ je: ] | Ё ё [ o ] [ jo ] | Ё̄ ё̄ [ o: ] [ jo: ] | Ж ж [ ʒ ] |

| З з [ z ] | ' ¹ / һ Һ ² [ ʰ ] ~ [ h ] | И и [ i ] [ ji ] | Ӣ ӣ [ i: ] [ ji: ] | Й й [ j ] | Ҋ ҋ ¹ / Ј ј ² [ j̊ ] |

| К к [ k ] | Л л [ l ] | Ӆ ӆ [ l̥ ] | М м [ m ] | Ӎ ӎ [ m̥ ] | Н н [ n ] |

| Ӊ ӊ [ n̥ ] | Ӈ ӈ [ ŋ ] | О о [ o ] | О̄ о̄ [ o: ] | П п [ p ] | Р р [ r ] |

| Ҏ ҏ [ r̥ ] | С с [ s ] | Т т [ t ] | У у [ u ] | Ӯ ӯ [ u: ] | Ф ф [ f ] |

| Х х [ x ] | Ц ц [ ts ] | Ч ч [ tʃ ] | Ш ш [ ʃ ] | Щ щ ³ | Ъ ъ |

| Ы ы [ ɨ ] | Ь ь | Ҍ ҍ | Э э [ e ] | Э̄ э̄ [ e: ] | Ӭ ӭ [ e ] |

| Ю ю [ u ] [ ju ] | Ю̄ ю̄ [ u: ] [ ju: ] | Я я [ a ] [ yes ] | Я̄ я̄ [ a: ] [ yes: ] |

Remarks:

- 1marks two letters found in Sammallahti et al. (1991) are needed; most Kildin Sami books published in Norway since the 1990s use this variant of the alphabet.

- 2marks the two corresponding letters used in Afanas'eva et al. Used in 1985; most of the books published in Russia since the 1980s use this variant of the alphabet.

In Antonova's primer (1982) and Kert's dictionary (1986) these letters are not used at all. - 3 occurs only in Russian loanwords.

As in other Cyrillic alphabets, some letters mark (alone or alongside their vowel value) features of the preceding consonant:

- е / ӭ, ё, и, ю, я / ä stand for the respective vowels [e], [o], [i], [u], [a] following a palatalized consonant.

- ь / ҍ marks the palatalization of the preceding consonant (except after н, here ь marks that it is a palatal consonant [ɲ]).

- ъ marks the non-palatalization of the preceding consonant.

Long vowels are marked with a macron (¯) above the vowel letter.

Phonotactics

In general, it can be said that the syllable structure of the Kildinsamian language is closely related to its stressing patterns: While stem-initial syllables are usually stressed, non-initial syllables are unstressed. Furthermore, the syllable types that occur in two-syllable stems can be traced back to the Proto-Saami. On the other hand, the nucleus of the syllable must be a vowel, so that no consonantic syllable kernels occur. Finally, it is assumed that the Maximum Onset Principle (MOP) applies in the Kildinsaami. This means that consonant material, which phonotactically could be both the coda of the last syllable and the onset of the following syllable based on the sonority hierarchy, is structurally realized as an onset. This is justified by the fact that first-time speakers intuitively separate syllables according to these rules and that word-final, aspirated plosives lose their aspiration if a syllable without an onset follows in the intonation curve.

The literature on the Kildinsamian language also points to the concept of the consonant center: between the initial and following syllables of the stem as well as after monosilbic stems there are necessarily single consonants, geminates or consonant clusters. In the consonant center there are therefore more possible combinations of consonant material than in other phonotactic positions. The onset of the initial syllable, on the other hand, is either empty or contains a single consonant, which must be either sonorant or voiceless obstruent. Loan words are excluded from this. It can also be seen that initial syllables have a mandatory coda, while non-initial syllables always have an onset. The syllable-initial onset and the non-syllable-initial coda, on the other hand, are optional.

In his research, Joshua Wilbur (2008) comes up with ten syllable types that exist in Kildin Sami. Their occurrence depends on whether they are monosilbic or parts of multisilbic words and whether they occur initially, internally or finally.

| Syllable type | example | glossary |

|---|---|---|

| SC | [jud] | plate \ GEN: SG |

| LC | [͜Tʃa: n] | devil \ NOM: SG |

| SG | [man'] | egg \ NOM: SG |

| LG | [man] | moon \ NOM: SG |

| SCC | [sɛrv] | moose \ GEN: SG |

| LCC | [jo: rt] | think \ 3.SG: PRS |

| SGC | [piŋŋk] | wind \ NOM: SG |

| LGC | [sɛ: rrv] | moose \ NOM: SG |

| S. | [sunn. t-ɛ ] | melt \ INF |

| L. | [ yes: .la] | live \ 1st SG: PRS |

| Legend: S = short vowel, L = long vowel, C = consonant, G = geminate, CC = consonant cluster | ||

On this basis, Wilbur comes up with two models of prototypical syllables in Kildinsaami:

initial: (C 0 ) V (:) C (:) 1 (C 2 )

non-initial: C 0 V (:) (C (:) 1 ) (C 2 )

Brackets enclose optional elements, while numbers represent the numbering of consonants.

Phonology

General

With 54 consonants (omitted length), the Kildinsamian language has a fairly large consonant inventory. The vowel inventory, on the other hand, is much less pronounced with 7 vowels (length omitted). Both palatalization and the difference in quantity in vowels and consonants play a major role in Kildin Sami.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio

Dental |

Alveolar | Post Office-

Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p (ː) b (ː)

p (ː) ʲ b (ː) ʲ |

t (ː) d (ː)

t (ː) ʲ d (ː) ʲ |

k (ː) g (ː)

k (ː) ʲ g (ː) ʲ |

||||

| nasal | m̥ (ː) m (ː)

m̥ (ː) ʲ m (ː) ʲ |

n̥ (ː) n (ː)

n̥ (ː) ʲ n (ː) ʲ |

ɲ (ː) | ŋ (ː)

ŋ (ː) ʲ |

|||

| Vibrant | r̥ (ː) r (ː)

r̥ (ː) ʲ r (ː) ʲ |

||||||

| Fricative | f (ː) v (ː)

f (ː) ʲ v (ː) ʲ |

s (ː) z

s (ː) ʲ zʲ |

ʃ (ː) ʒ

ʃ (ː) ʲ ʒʲ |

x (ː)

x (ː) ʲ |

H

H |

||

| Affricates | t͡s (ː) d͡z

t͡s (ː) ʲ d͡zʲ |

t͡ʃ (ː) ʲ d͡ʒʲ | |||||

| Lateral | l̥ (ː) l (ː)

l̥ (ː) ʲ l (ː) ʲ |

ʎ (ː) | |||||

| Approximant | j̥ (ː) j (ː) |

Voiceless sounds are on the left, voiced sounds on the right

Every consonant can be lengthened except / z /, / d͡z /, / ʒ / and / d͡ʒ /, with phonemic differences in length only occurring in the consonant center. The Kildinsamian language contrasts non-palatalized, palatalized and palatal sounds of the same place of articulation and the same type of articulation.

Geminates

Geminates also only occur in the consonant center and contrast there with their individual sound counterparts. Wilbur (2007) gives an example of a minimal pair and an almost minimal pair.

| example | glossary |

|---|---|

| / seːrrv / | 'Moose \ SG' |

| / seːrv / | 'Moose \ PL' |

| / saːrrn-ip / | 'speak-1PL' |

| / saːrn-a / | 'speak-1SG' |

Single consonants with a geminate correlate, on the other hand, can occur at every syllable initial position in the word as well as in the consonant center.

Voiced obstruent geminata phonemes are only voiced at the beginning and become voiceless at the end. For example, / b: / is implemented as [bp] or / d͡z: / as [dts]. The fact that the plosive geminates are actually partially voiced and not two individual sounds can be seen from a single locking solution at the end of the segment. They cannot be represented by a purely voiceless geminate either, e.g. B. / p: /, as their half voicedness or voicelessness suggests, since purely voiceless geminates trigger pre-aspiration. So the phoneme / p: / is realized phonetically as [ʰp].

Monophthongs

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | i | ɨ | u |

| Half closed | e | O | |

| Open | a | ɒ |

Each of these vowels has a long and a short variant to which the phoneme status is assigned, which means that there are a total of 14 monophthong phonemes in Kildin Sami. As already mentioned in the Spelling section, these differences in quantity are identified by a macron.

The rounded open back vowel [ɒ] is given in some sources as its unrounded counterpart.

Diphthongs

Depending on the source, the Kildin Sami language has 3–4, partly differing, diphthong phonemes: / e͜a /, / i͜e /, / u͜a /, / u͜e / or / o͜a /, / u͜e /, / u͜a /.

The diphthongs of Kildin Sami also show differences in quantity.

Palatalization

In the Kildinsamian language, all places of articulation, except for the palatal sounds, have a palatalized counterpart. This is only inherent in the Saami languages on the Kola Peninsula, which is why it was previously claimed that this was borrowed from Russian, which is in close linguistic contact with Russian (Kert 1994). Kusmenko and Rießler (2012) refute this on the basis of etymological data within the language, but admit that Russian “could have been a catalyst in development”.

Also mentioned in modern Russian-language literature on Kildinssamian phonology (Kert 1971) is the phenomenon of “half-palatalization” in connection with the dental consonants / t, d, n /. This is also referred to in the orthography with the historical Cyrillic grapheme yat <ѣ> in contrast to the grapheme for the "full palatalization" <ь>. Wilbur finds no evidence in his data that it is based on actual phonetic or phonological differences and excludes the consonants "half-palatalized" by <ѣ> as a mere orthographic convention from the phoneme inventory.

If the Latin transcription is used, a <'> marks the palatalization of the previous segment.

A possible three-way contrast between non-palatalized, palatalized and palatalized sound would be:

| According to | word | phonological

transcription |

glossary |

|---|---|---|---|

| alveolar nasal | man | / maːnː / | Moon / month |

| alveolar nasal (palatalized) | man' | / manːʲ / | egg |

| palatal nasal | mannj | / maɲː / | daughter in law |

Palatalization in the Kildin Sami language is a non-linear morphosyntactic process that causes the palatalization or de-palatalization of the consonant center in certain morphophonological environments. Wilbur gives four examples:

| example | glossary |

|---|---|

| / jorrt-a / | 'think-1SG' |

| / jorrt / | 'think \ 3SG' |

| / jurrʲt-e / | 'think-INF' |

| / jurrʲt-ip / | 'think-1PL' |

Here the stem jurrʲt 'think' loses its palatalization in connection with morphemes indicating singular, while it is retained for infinitive and plural. At the synchronous language level, palatalization is based on morphological paradigms, but can also be explained by historical language data. Through a process of regressive assimilation, older closed and semi-closed front tongue vowels of the second syllable have caused a palatalization of the preceding consonant center.

While this process can historically be explained by the disappearance of trigger material, it is important to note that this process has now become neither predictable nor productive. Instead, it is determined by the inflection class of the lexemes to which it belongs. Since these cannot be separated in a linear manner from the stems that they modify, Wilbur concludes that they are true non-linear morphemes themselves, or at least non-linear parts of otherwise externalizable suffixes.

Prosody

As already mentioned in the phonotactic part, the syllable structure of Kildin Sami correlates with the word stress, but also with the length contrasts.

Word stress

Since a stressed syllable is always contrasted with an unstressed syllable in Kildin Sami, it makes sense to use the metric feet to represent the word stress. A foot is a metric unit of rhythm and therefore plunges into word stress. In Kildinsami they are structured trochaic, i. H. the initial syllable of each foot is stressed.

In addition, the Kildinsamischen has a complex system of secondary accents in polysyllabic words, whereby it depends on the number of syllables.

In polysyllabic words, the first syllable is stressed, the secondary stress then falls on the third syllable, but if it is also the last syllable, it becomes unstressed.

quantity

Contrasts in vowel quantity (based on the data from Wilbur) are only typical for initial syllables and only for simple syllable structures - short vowel consonant vs. Long vowel consonant. Unstressed vowels are mostly short.

The same applies to length contrasts in consonants: There is typically a contrast between long and short consonants in monosyllabic words, in polysyllabic words contrasts only occur in the initial syllable.

intonation

For Kildin Sami, as for the other natural languages of the world, declination is typical, which shows itself in a gradual decrease of the fundamental frequency or pitch in the course of an utterance unit.

grammar

Level change

Like North Sami, Kildin Sami also uses the level change . This is usually the only way of telling the difference between nominative singular and genitive / accusative singular in words. The following table illustrates the level change from the strong level in the nominative to the weak level in the genitive / accusative.

| Type | Nominative | Genitive / accusative | meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| bb> pp | oabbá | oappá | 'Sister' |

| dd> tt | loddi | lotti | 'Bird' |

| hk> g | johka | yoga | 'Flow' |

| hc> z | čeahci | čeazi | 'Uncle' |

| pm> m | sápmi | sámi | 'Samiland' |

| tn> n | latnja | lanja | 'Room' |

| ld> ldd | balance | salddi | 'Bridge' |

| rf> rff | márfi | márffi | 'Sausage' |

In the last two examples it is also clear that the weak level is not shortened, but lengthened.

case

Kildinsamische has nine cases : nominative , genitive , accusative , illative , locative , comitive , abessive , essive and partitive . However, the genitive and accusative have the same form.

noun

In Kildinsami there are five distinct classes of inflection within the nominal morphology , but since one of these classes only determines the diminutive , the number of classes mentioned varies within the literatures. The nominal inflections are formed in Kildinsamischen by adding inflexional suffixes to the lexical stems. Since suffixes in Kildin Sami can be added not only to the root but also to other suffixes, the following sequence of suffixes applies: word stem - derivational suffix - number marker - case suffix - possessor suffix (- enclitonic).

| case | Class I.

'Aunt' |

Class II

'Ground' |

Class III

'Woman' |

Class IV

'Reindeer' |

Class V

'Wind / small wind' |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | kuess'k | vuedd | nozan | puaz | piiŋ'ka |

| Gene. | kues'k | vued | nozan | puudz-e | piiŋ'ka |

| Acc. | kues'k | vued | nozan | puudz-e | piiŋ'ka |

| Ill. | kuassk-a | vuudd-e | nozn'-e | puudz-je | piiŋ'k-n'e |

| Loc. | kues'k-es't | vued-es't | nozn-es't | puudz-it't | piiŋ'k-as't |

| Com. | kuus'k-en ' | vued-en ' | nozn-en ' | puudz-en ' | piiŋ'k-an ' |

| Abe. | kues'k-xa | vued-xa | nozn-ahta | puudz-ahta | piiŋ'k-ahta |

| Eating | kuess'k-en ' | vuedd-en ' | nozn-en ' | puudz-en ' | piiŋ'k-an ' |

| Part. | kuess'k-e | vuedd-e | nozn'-edd'e | puudz-jedd'e | piiŋ'k-n'edd'e |

| case | Class I. | Class II | Class III | Class IV | Class V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nom. | kues'k | vued | nozan | puudz-e | piiŋ'ka |

| Gene. | kuus'k-e | vued-e | nozn-e | puudz-e | piiŋ'ka |

| Acc. | kuus'k-et ' | vued-et ' | nozn-et ' | puudz-et ' | piiŋ'k-at ' |

| Ill. | kuus'k-et ' | vued-et ' | nozn-et ' | puudz-et ' | piiŋ'k-at ' |

| Loc. | kuus'k-en ' | vued-en ' | nozn-en ' | puudz-en ' | piiŋ'k-an ' |

| Com. | kuus'k-eguejm | vued-egujm | nozn-eguejm | puudz-eguejm | piiŋ'k-aguejm |

| Abe. | kuus'k-exa | vued-exa | nozn-exa | puudz-exa | piiŋ'k-axa |

Verbal inflection

The Kildensaamische language has different inflection classes, which in turn can be divided into two superordinate inflection paradigms: on the one hand verbs in which there is a change in level, on the other hand verbs without a change in level.

Kildinsami has both infinite - with the categories infinitive, gerund and participle and finite verbal inflection.

Finite verbal inflection

The finite verbal inflection includes the categories mode, time, number, and person, which are expressed in box morphemes. These box morphemes of the two inflection paradigms are similar and are the same within the respective inflection class.

The modes of the Kildenammic are indicative, conditional ( COND ) and imperative ( IMP ). The mode of potential ( POT ), which occurs in Skoltsaamischen , is, apart from the verb “to be”, not available.

In Kildensaamischen there are two synthetic tenses (i.e. tenses that are not composed of several components) of the indicative: on the one hand the "non-past" (English: Nonpast, NPST ), which is used to describe everything that is not in the past and on the other hand the past (English Past, PST ).

As in German, the verbs inflect after singular and plural, in the 1st – 3rd. Person. In addition, there is also a so-called "4th person", who is often referred to as Impersonal ( IPS ) and which can be translated as "one" or "someone". The Impersonal category only exists in the indicative.

Inflection tables (exemplary)

Below are examples of verbal inflections of both inflection classes. The suffixes separated by a hyphen indicate the respective ending of the verb form.

Verbs with a change of level

| INF | jiell'-e (life) | saarn-e (talking) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | ||

| NPST | 1st person | jaal-a | jiell'-ep ' | saarn-a | saarn-ep ' |

| 2nd person | jaal-ak | jiell'-bedd'e | saarn-ak | saarrn-bedd'e | |

| 3rd person | yeah | jiell'-ev | saarrn | saarn-ev | |

| IPS | jiel'-et ' | saarn-et ' | |||

| PST | 1st person | jill'-e | jiil'-em | sooaarr-e | saarn-em ' |

| 2nd person | jill'-ek ' | jil'-et ' | sooaarr-ek ' | saarn-et ' | |

| 3rd person | jiil'-e | jiill-en ' | saarn-e | sooaarr-en ' | |

| IPS | jiil'-eš ' | sooaarr-eš ' | |||

| COND | 1st person | jaal-če | jaal-čep ' | sooaarn-če | sooaarn-čep ' |

| 2nd person | jaal-ček ' | jaal-čepb'e | sooaarn-ček ' | sooaarn-čepb'e | |

| 3rd person | jaal-ahč | jaal-čen | sooaarn-ahč | sooaarn-čen | |

| IMP | jiel | jiell'e | saarn | saarrn-e | |

What is noticeable about this class of inflection is the highly complex level change, through which the stem of the verb takes five different forms, whereby certain stems are only characterized by marginal changes. By this level change, it is possible to use the same extensions for different verb forms, since in that case the strains differ from each other (see. For example, 1st and 3rd person singular PST and IMP singular), without thereby a Formensynkretismus comes . The distribution of the respective stems to the individual persons, tenses and modes differs depending on the verb, but certain regularities can still be determined:

- the change of level is most common in the indicative ( NPST / PST )

- the 3rd person singular of the "non-past" ( NPST ) does not have its own ending, this form also functions as a stem for other forms, the same applies to the imperative ( IMP )

- the conditional ( COND ) has a uniform stem that does not correspond to that of the infinitive

Verbs without changing levels

| INF | vaan'c-le (go away) | lygk-ne (move) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | ||

| NPST | 1st person | vaann'c-la | vaann'c-l-ep ' | lygk-na | lygk-n-ep ' |

| 2nd person | vaann'c-l-ak | vaann'c-l-ebp'e | lygk-n-ak | lygk-n-ebp'e | |

| 3rd person | vaann'c-al | vaann'c-l-ev ' | lygk-ant | lygk-n-ev ' | |

| IPS | vaann'c-l-et ' | lygk-n-et ' | |||

| PST | 1st person | vaann'c-le | vaann'c-l-em ' | lygk-ne | lygk-n-ep ' |

| 2nd person | vaann'c-l-ek | vaann'c-l-et ' | lygk-n-ek | lygk-n-ebp'e | |

| 3rd person | vaann'c-el ' | vaann'c-l-en ' | lygk-en't | lygk-n-ev ' | |

| IPS | vaann'c-l-eš ' | lygk-n-eš | |||

| COND | 1st person | vaann'c-l-ehče | vaann'c-l-ehčep ' | lygk-n-ehče | lygk-n-ehčep ' |

| 2nd person | vaann'c-l-ehček ' | vaann'c-l-ehčet ' | lygk-n-ehček ' | lygk-n-ehčet ' | |

| 3rd person | vaann'c-l-ahč | vaann'c-l-ehčev | lygk-n-ahč | lygk-n-ehčev | |

| IMP | vaann'c-l-el ' | vaann'c-l-egke | lygk-n-en't | lygk-n-egke | |

The verbs that belong to this inflection paradigm do not have a change of stage, in order to avoid syncretism, each verb form has a different ending. A special feature of these verbs is the 3rd person singular of the indicative. It is assumed that there is a slot (ie a "place" where.) In front of the last consonant of the infinitive ending ("l" or "n") grammatical information can be inserted). This is indicated by the first hyphen. This assumption is based on the fact that the verb forms concerned are characterized by the fact that the ending begins before the last consonant.

To be the verb"

The inflection of the verb "sein" in Kildensaamischen is irregular and, as already mentioned, is the only verb that has the category of potential ( POT ). In addition, the Impersonal category is missing.

| INF | liije (to be) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||

| NPST | 1st person | l'aa | l'eebp ' |

| 2nd person | l'aak | l'eebpe | |

| 3rd person | lii | l'eev | |

| PST | 1st person | liije | liijem ' |

| 2nd person | liijek ' | liijet ' | |

| 3rd person | l'aai | liijen ' | |

| COND | 1st person | liiče | liičem |

| 2nd person | liiček ' | liičet | |

| 3rd person | l'aač | liičen ' | |

| POT | 1st person | liinnče | linncep ' |

| 2nd person | linnček | linnčbedt'e | |

| 3rd person | l'aannč | linnčev | |

Analytical time formation

In addition to the synthetically formed times listed above, Kildensaamische also has three analytical -d. H. tenses composed of several elements: future, perfect and past perfect; The latter only occurs in the written language. These tenses are all formed with a form of "sein" and an infinite verb form (infinitive, participle).

For example, the future tense is formed with the potential of "sein" and the infinitive:

munn liinče jiell'-e

1.SG sein:POT.1.SG leben-INF

„Ich werde leben“

negation

In Kildin Sami, a syntagm is used to express negation, which consists of a finite negative verb and a finite main verb in the connegative (negative form of the main verb). The finite negation verb is also known as the negation auxiliary, since it fulfills the function of an auxiliary verb. It is inflected according to person, number and mode. The main verb of the sentence is presented in a special form called a connegative. The tense (present or past) is always marked on the main verb. The negative verb has the same form in all tenses.

The inflectional paradigm of the negative verb looks like this:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | emm | jie'bb |

| 2nd person | egg | jie'bbe |

| 3rd person | ejj | jiev |

| Impersonal | jie'dt | |

| imperative | jie'l | jie'lle |

Negated sentence in the present tense:

Mun emm t'ēd', koal'e Evvan lī puadtma.

Ich ich.nicht weiß, ob Ivan ist gekommen.

„Ich weiß nicht, ob Ivan gekommen ist.“

Negated sentence in the past:

Sōnn ejj t'ēdtma koal'e sōnn jo ujjtma li

Er/Sie er/sie.nicht wusste ob er/sie bereits gegangen ist.

„Er/Sie wusste nicht, ob er/sie bereits gegangen ist.“

The negation of the verb “sein” in the third person leads to a fusion of the main and auxiliary verb. The following forms are created:

ell´a = "is not", composed of ejj (3rd person sg. negation verb) and lea (connegative, present tense, main verb: "to be")

jievla = "are not", composed of jiev (3rd person pl. negation verb) and lea (connegative, present tense, main verb: "to be")

ell´ij = "was not", composed of ejj (3rd person sg. negative verb) and liijja (connegative, past, main verb: "to be")

Exclusively in the 3rd person plural of the past tense there is no fusion of the negative verb and the main verb "sein":

jiev liijja = "weren't", composed of jiev (3rd person pl. negative verb) and liijja (connegative, past, main verb: "to be")

Negated indefinite pronouns are constructed in Kildin Sami using the negation prefix ni . It is the only prefix of the Kildinsamian language and was borrowed from Russian. The prefix ni- is used with all interrogative pronouns. The negated indefinite pronouns can be derived in different cases. Examples are:

ni-k'ē neg-who? Nominative, singular "nobody"

ni-k'ējn Neg-Who? Comitive, singular "With nobody"

ni-k'ēnn Neg-Who? Genitive, singular "nobody"

ni-mī neg-what? Nominative, singular "nothing"

ni-mēnn Neg-What? Accusative, singular "nothing"

ni-mēnn munn emm ujn.

Was.nicht ich ich.nicht sehe.

„Ich sehe nichts.“ (Wörtlich in etwa: „Ich nicht sehe nichts“).

Complementation

The Kildinsamischen forms sentence structure according to the pattern matrix sentence - subjunction - subordinate sentence. The subordinate sentence may a. are introduced by šte (that), koal'e or jesl'e (ob / if) and by interrogative pronouns or adverbs . It can be dependent on the content of the matrix sentence (as a subject or object sentence) or as an adverbial sentence to describe a circumstance.

Subject sentence:

kaj mīll'te kūsstaj [šte ell'a šīg kūll']. Gesicht mit wird.sichtbar [dass ist.nicht gut Fisch] „Es war zu sehen, dass der Fisch nicht gut war.“

Object set:

munn jurta [šte tedd lī čofta važne [mun kīl' ōhpnuvve] ]. ich denke [dass das ist sehr wichtig [meine Sprache lernen] ] „Ich denke, dass es sehr wichtig ist, meine Sprache zu lernen.“

Adverbial clause:

[...] milknes't [šte ejj miejte sīnet]. langsam [dass/damit er.nicht zermatscht sie] („Er legt die Birnen) langsam (ab), damit er sie nicht zermatscht.“

[koal'e tɨjj ann'tbedt'e mɨnn'e ājk] munn jurr'tla tenn bajas. [wenn du gibst mir Zeit] ich denke.nach das über „Wenn du mir etwas Zeit gibst, denke ich darüber nach.“

In contrast to the equivalents Skoltsamisch što and North Sami ahte , Kildinsamisch šte cannot stand in front of any other introduced sentences. Direct speech is also often added without an šte.

Instead of content-related sentences with koal'e (ob), uninitiated decision-making questions can be used:

mun emm t'ēd' [koal'e Evvan lī puadtma].

ich ich.nicht weiß [ob Ivan ist gekommen].

„Ich weiß nicht, ob Ivan gekommen ist.“

mun emm t'ēd' [lī Evvan puadtma].

ich ich.nicht weiß [ist Ivan gekommen].

„Ich weiß nicht, ob Ivan gekommen ist.“

Šte can come after deictic expressions and the subordinate sentence z. B. give a causal meaning:

[…] tenn guejke šte mīnen' kīll lī mōǯes', mōǯes’ kīll.

das wegen dass bei.uns Sprache ist schön schön Sprache

„... weil (aufgrund dessen, dass) wir eine schöne Sprache haben.“

vɨjt'e nɨdt’ šte ...

es.ergab.sich so dass ...

„Es ging so aus, dass ...“

As can be seen in the example above for an object sentence with šte , an infinitive structure can also represent a subject as subordinate.

Pragmatics

Pragmatics deals with the content of utterances. Particular attention is paid to the linguistic expression that is articulated by a speaker and perceived by a listener. Here, a distinction can be made between context-dependent expressions, which relate to the context of a certain situation, and the non-literal meaning, the content actually intended by the speaker.

The pragmatics in Kildin Sami is still an unexplored area to this day. So far there has not been any concrete field research that deals solely with the question of how exactly Kildinsamian speakers use their language. Nevertheless, one can make assumptions on the basis of the available data.

Deixis

Deixis describe the reference to people, localities, tense, discourse and the social role in a concrete utterance with the help of deictic expressions.

Examples of deictic expressions include personal pronouns, adverbs, places or times.

Personal Deixis

In order to refer to a person in an utterance, the speaker uses personal pronouns and possessive pronouns, among other things. The Kildin Sami does not differ from the German language. Only the lack of gender difference is a specialty in Kildin Sami. The speakers use a gender-neutral pronoun.

| German | Kildin Saami |

|---|---|

| I | munn |

| you | toonn |

| he she | soonn |

Kildinsaamisch: "Munn leä Anna."

German: "I am Anna."

| German | Kildin Saami |

|---|---|

| my | mun |

| your | toon |

| his / her | soon |

Kildin Saami: "Mun nõmm lii Anna."

German: "My name is Anna."

Ort deixis

Relation to a locality in an utterance is often used through local adverbs. The word “ta'st”, in English “here”, is an example of a local dictic expression in Kildin Sami.

One difference to German is that Kildin Sami uses the locative. By using it, location information is indicated.

Kildinsaamisch: "Munn jaala Bielefelds't."

German: "I live in Bielefeld."

The location is indicated by the final ending.

Temporal deixis

There are several options for referring to the time in an utterance. The dimension of time is described by the different tenses such as the past, present and future tense, but also adverbs of time.

The above example of a local deixis “Munn jaala Bielefelds't” can accordingly also refer to time. Since the verb “jaala”, in German “to live”, is in the present tense, one can assume that the speaker currently lives in Bielefeld.

Discourse deixis

Discourse deictic expressions refer to utterances that have already been made. Examples in German would be demonstrative pronouns like "this" or the adverb "also". The following example explains how discourse deictic expressions are used.

Kildin Saami: "Kiirhk-es't lii čall'm ruupps-e."

German: "The ptarmigan has a red eye."

Kildin Saami: "Tes't čalʹm jevla ruups-e ujn-ak."

German: "Here the eyes are not red, you see."

“Tes-t”, in English “here”, refers in this example to the ptarmigan mentioned in the first sentence. It is both a place case and a discourse deictic expression that creates a reference to a previous utterance.

Social deixis

Social deictic expressions indicate a person's social status or the relationship between those in the conversation. In German, the politeness form is used for a business or a distant relationship. This form of courtesy exists in Kildin Sami based on the Russian model of courtesy, but is rarely used. The polite form is rarely used among the Kildinsaamen, but field researchers' experience reports say that they have experienced the polite form very well. They then put forward the assumption that the form is definitely used towards strange, new people of respect.

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c d Joshua Wilbur: Syllable Structures and Stress Patterns in Kildin Saami. (PDF) 2008, accessed on November 16, 2017 (English).

- ↑ a b Michael Rießler: Kildin Saami . In: Marianne Bakró-Nagy, Johanna Laakso, Elena Skribnik (eds.): Oxford Guide to the Uralic languages . Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ↑ Timothy Feist: A Grammar of Skolt Saami . In: Diss. University of Manchester, Manchester 2010.

- ↑ Kristina Kotcheva and Michael Rießler: Clausal complementation in Kildin, North and Skolt Saami . In: Kasper Boye and Petar Kehayov (eds.): Complementizer Semantics in European Languages (= Empirical Approaches to Language Typology . No. 57 ). De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin 2016, p. 499-528 , doi : 10.1515 / 9783110416619-015a .

- ↑ Michael Rießler: Kildin Saami . In: Yaron Matras, Jeanette Sakel (Ed.): Grammatical borrowing in crosslinguistic perspective (= Empirical Approaches to Language Typology . No. 38 ). De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin 2007, p. 229-244 , doi : 10.1515 / 9783110199192.229 .

- ↑ Kristina Kotcheva, Michael Rießler: clausal complementation in Kildin, Skolt and North Saami . In: Kasper Boye, Petar Kehayov (Ed.): Complementizer semantics in European Languages . De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2016, ISBN 978-3-11-041651-0 , p. 487-516 .

- ↑ a b WIKITONGUES: Anna speaking Kildin Saami. September 7, 2016, accessed March 7, 2018 .

literature

- Aleksandra A. Antonova : Saam 'bukvar': bukvar 'dlja podgotovitel'nogo klassa saamskoj školy . Leningrad 1982.

- AA Antonova; N. each. Afanas'eva ; Ever. I. Mečkina; LD Jakovlev; BA Gluhov (Red. Rimma D. Kuruč): Saamsko-russkij slovar '= Saam'-rūšš soagknehk . Moskva 1985.

- Georgij M. Kert : Saamskij jazyk (kil'dinskij dialect): fonetika, morfologija, sintaksis . Leningrad 1971.

- Georgij M. Kert: Slovar 'saamsko-russkij i russko-saamskij . Leningrad 1986.

- Kristina Kotcheva; Michael Rießler: Clausal complementation in Kildin, North and Skolt Saami . In: Complementizer Semantics in European Languages . Edited by Kasper Boye and Petar Kehayov. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin 2016, pp. 499-528. doi: 10.1515 / 9783110416619-015a (= Approaches to Language Typology , 57)

- Rimma D. Kuruč; N. each. Afanas'eva; IV Vinogradova: Pravila orfografii i punktuacii saamskogo jazyka . Murmansk, Moskva 1995.

- Jurij K. Kuzmenko ; Michael Rießler: K voprosy o tverdych, mjagkich i polumjagkich soglasnych v kol'skosaamskom . (PDF) In: Acta Linguistica Petropolitana , Vol. 1: Fenno-Lapponica Petropolitana. Ed. by Natal'ja V. Kuznecova; Vjačeslav S. Lulešov; Mechmet Z. Muslimov. Trudy Instituta lingvističeskich issledovanij, RAN 8. Nauka, Sankt-Peterburg 2012, pp. 20–41

- Michael Rießler: Kildin Saami . In: Grammatical borrowing in crosslinguistic perspective . Edited by Yaron Matras and Jeanette Sakel. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin 2007, pp. 229-244. doi: 10.1515 / 9783110199192.229 (= Approaches to Language Typology , 38)

- Michael Rießler: Towards digital infrastructure for Kildin Saami . (PDF) In: Erich Kasten; Tjeerd de Graaf (Ed.): Sustaining Indigenous Knowledge: Learning tools and community initiatives on preserving endangered languages and local cultural heritage . Verlag der Kulturstiftung Sibirien, Fürstenberg 2013, pp. 195–218.

- Pekka Sammallahti: The Saami languages . Karasjok, 1998.

- Elisabeth Scheller: The language situation of the Saami in Russia . (PDF) In: Antje Hornscheidt ; Kristina Kotcheva; Tomas Milosch; Michael Rießler (ed.): Grenzgänger: Festschrift for the 65th birthday of Jurij Kusmenko . Northern Europe Institute at Humboldt University, Berlin 2006, pp. 280–290. (= Berlin contributions to Scandinavian Studies , 9)

- Joshua Wilbur: Syllable Structures and Stress Patterns in Kildin Saami . University of Leipzig, 2008.