Coolie (day laborer)

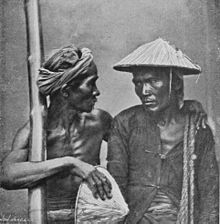

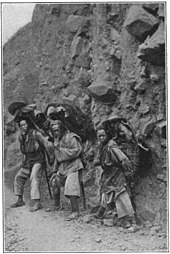

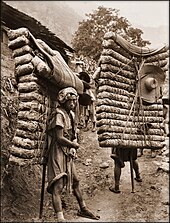

As a coolie ( English coolie ) predominantly Chinese and South Asian unskilled wage workers in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, who worked for a company as contract workers or day laborers . They were mainly used on plantations , in coal mines , as load carriers or for other low-paid physical activities.

The recruitment of coolies was often done under duress and using methods that corresponded to the slave trade . The majority of those affected were taken to British colonial areas in Southeast Asia and Central and South America. Due to the forced demarcation and exclusion in the target countries, the diaspora of the overseas Chinese developed .

The word coolie has been used as a term for porters at train stations in different countries , depending on the situation it can be understood derogatory.

etymology

According to the etymological dictionary of the German language , the word Kuli goes back to English coolie and Hindi कुली kulī "load carrier", the name of an ethnic group in the north-west Indian Gujarat whose members often hired themselves as wage laborers. A possible origin from the Tamil கூலி kūli, "wage, day wage", is suggested.

Another theory suggests the origin in a Turkic language , Chagatai , the language of Babur , which conquered northern India in the 16th century. This is indicated by the Turkish word kul with the meaning "servant, slave". In this case, the word via Urdu qulī would have spread to other languages in India.

The word came into Chinese later. There it looks like a Chinese compound in the form 苦力 , kǔlì . The meaning of “ 苦 , kǔ ” is namely “bitter, hard” and “ 力 , lì ” can be understood as “work force”. This is why the origin of the word has occasionally been suggested in Chinese.

Dutch koelie was also the name for the contract workers (Dutch contractarbeiders ) in the Dutch East Indies between around 1820 and 1941.

history

Since the Congress of Vienna in 1814, the slave trade was banned worldwide, in the USA only in 1864. As a result, black slaves as cheap workers were lacking in the overseas colonies. The resulting gap was quickly closed by Blackbirding and, to an enormous extent, by the so-called Indentured Labor , a system of contract labor introduced worldwide in 1806 by the British . Indian workers were affected, and from 1840 mostly Chinese workers who were given the name coolies on the basis of the indenture contracts .

The procurement of coolies was often associated with deportation and was largely carried out via main transhipment points such as Hong Kong , Canton and especially Macau . Predominantly young men were locked up in "prison-like, low barracks" (barracoons), often under false promises, under duress and sometimes by kidnapping, and later shipped. In these depots, "the coolies were stored in a way that, without exaggeration, can be described as inhuman," as the German consulate reported to Berlin in 1902. The occupants of the barracoons got, often with the use of force, on mostly overcrowded steamships . The conditions of accommodation, food and passage were often so unbearable that there were not only numerous deaths, but repeated revolts and mutinies.

Almost all nations that traded in East Asia were involved in the pen trade. Hundreds of thousands of workers were moved from Hong Kong and Macau to Singapore , where a large Chinese diaspora was established during the 19th century . Singapore developed into the most important "coolie trading point". From there, the “emigrants” were shipped to Africa, North, Central and South America and all of Southeast Asia in officially so-called Kulipassagen. The transport of people from China to Singapore was almost exclusively done by British shipping companies in liner shipping .

Among the 289 steamers that brought Chinese workers to Singapore in regular continuous operation, for example in 1890, there was only one Chinese ship. However, less than ten years later, the Chinese, who had acquired British citizenship in Singapore, took part in the "coolie export" and set up their own steamship lines under the British flag. The greatest need for cheap labor was in the British and French colonies. German entrepreneurs also recruited coolies to work in individual German colonies .

The transport to North and South America took place with American, but mostly also with British ships and brought the traders and captains the highest profits. Many Chinese died on the crossing. For those who reached the destination country, it often had nothing more to offer than China itself. Coolies were often used for hard work on the plantations, in mines or, in America, especially when building the railroad and in California mines. They had to sign a "coolie contract" by which they bound themselves to the respective company under strict conditions ( indenture ). A coolie had to work at least ten hours a day and was not allowed to leave the workplace without prior permission.

Young women and children were also kidnapped. The proportion of married women who found their way abroad was estimated to be less than 15 percent. That means that almost 85 percent of the deported women were young girls who were deliberately shipped as prostitutes , as the “yellow race” was supposed to stay among themselves. The fear of “racial mixing” united all colonial powers . In the USA and Australia, the xenophobic propaganda of the " yellow danger " already had a long history; in Europe, the xenophobic boom did not begin until the 1890s. It was a question of US and pan-European resentment against East Asian peoples, especially against the Chinese.

While the majority of European researchers in recent historiography do not deny the illegal methods of recruiting Chinese workers, not a few American historians claim, without being able to prove this, that “Chinese who went to North America almost without exception as free men with agricultural, manual or commercial work experience and not as coolies ”; they admit, however, that "against the background of the anti-Chinese propaganda of the time, Chinese immigrants in the USA were often pejoratively referred to as coolies."

In fact, American companies have been actively involved in human trafficking with the approval of the US government. Documented are, among other things, contemporary information from the captain of the Messenger , an American ship that regularly offered Kuli passages between San Francisco and Hong Kong. For example, on October 5, 1859, the captain noted in the logbook : "500 coolies on board, most, if not all, of which were kidnapped in the coastal regions."

Evidence shows that between 1870 and 1882, around 18,000 Chinese came to the USA every year via San Francisco alone. The Chinese Exclusion Act severely restricted immigration from 1882 onwards, but could be circumvented if the ships first called at ports in Central America. During and after the Philippine-American War , in which around one million Filipinos were killed, the new American colonial power used countless Chinese coolies as cheap labor in the colonies and protectorates of the United States . The pen trade of American companies continued via Hawaii and Cuba , where thousands of Chinese were employed to work on sugar cane plantations .

The violent recruitment of workers as Shanghai became part of the international seaman's language . The pen trade reached its peak between 1890 and 1911. The vast majority of Chinese coolies ended up in the British Straits Settlements and British colonies in the South Seas and Australia. Around 40,000 Chinese are said to have been shipped to Australia by 1858, after the British government stopped deporting prisoners to “ Down Under ” from the middle of the 19th century , which is why there was a shortage of labor, especially in Australian wool production.

After the turn of the century, many coolies were shipped to South Africa . As a result of the Second Boer War, there was a lack of cheap workers in the gold mines there, so that the British government forced the transport of Indian and Chinese coolies mainly to the Transvaal . Between June 1904 and November 1906 alone, 63,296 Chinese coolies arrived in the Transvaal colony.

The pen trade only collapsed after the founding of the Republic of China , after Sun Yat-sen consistently enforced the death penalty for human trafficking in China in 1912 - also proof that the majority of emigrations had not been voluntary until then.

Testimonies

A noteworthy contemporary document is a report by Pomeranian missionaries that appeared in the newspaper Evangelischer Reichsbote (excerpts, abbreviated) on November 1, 1873 under the heading The pen trade - An appeal to humanity in the 19th century :

“Didn't we think that with the victory of the North American Union, slavery was finally laid to its grave? As soon as the negro trade disappears on the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, the most worthless human traffickers pollute the shores of the Pacific . We are witnessing a relapse into slavery, the victim of which is the Asian coolie. The epidemic spread to other tropical and subtropical countries, particularly the Antilles , Central America, Guyana , Australia. Under the name of the freedom and emigration of Chinese workers, on the basis of a passage advance payment and a service contract, a system of human trapping, carefully planned in every detail, gradually emerged, in which all the experience of the most skillful commercial technology and the shipping industry with fraud, deceit, Violence, robbery and murder are so intimately woven that the victims of profit-seeking are, as it were, strangled in the noose of British law.

The main procedure is known. The most important staging area for the trade in fresh human meat is the Portuguese possession of Macau, located at the mouth of the Canton River . Since 1847, when the first emigration ships left there, the business has swelled to an almost unbelievable extent. The process is always the same and follows the tried and tested pattern: free passage to the American labor markets; in return, the obligation to work for eight years for a low wage, no more than 6 thaler per month ; Transfer of coolies to the highest bidder after arrival in America. In other words: the emigrant does not commit himself to a certain master or employer, but degrades himself in all forms to an object that is brought onto the market and, like a bale of cowhide, is sold dearly or cheaply depending on the economic situation.

A bad fate met those who were tortured to death on the Chincha Islands in South America with the extraction of guano . As early as 1860 it had been determined that of the 4,000 Chinese who landed on Guano Island alone, not a single one remained alive. The fate of the Chinese emigrants in the Middle Kingdom was not unknown. The means of capturing people in Macau were tightened all the more. Numerous slave depots were created, in which the Chinese coolies were stored in the time between their recruitment and shipment like in pantries. As soon as the coolie has passed the strictly guarded and barred entrance gate, it only opens once more for him when he is driven aboard the ship into the herd of his fellow sufferers.

According to all rules of the division of labor, the pen business is divided into several closely interlinked branches of business. The Anglo-French treaties of 1860 stipulate freedom from China to emigrate . Since then, British emigration offices have been opened in Canton and Hong Kong. On their behalf, various nationalities work as agents who receive a bounty for every piece of human being. Among them are Portuguese and Chinese crooks who can be called the scum of humanity. Impoverished Chinese are lured into gambling halls by them to drink and pay the debt for one night with their signature, which will cost them their freedom, their lives. Unsuspecting craftsmen and farmers are caught under fraudulent pretenses, and not infrequently also dragged away by kidnapping and kidnapping. Nobody in the southern Chinese coastal areas is protected against the acts of violence. All of these outrages take place in the deceptive forms of English contract law. The Chinese crook gets his percentage; the Portuguese procurator , who inspects the emigration ships in Macau, gets his share and finds everything in his revisions to be in accordance with regulations ; the captains and shipping companies get the lion's share .

How the coolies fare on the transport is well known to the public. Scattered in little newspaper notes, the news escapes sustained attention; they fall into the fate of oblivion with the disappearance of the newspaper number that brought them. The statistics perhaps achieve more than the repetition of such horror reports. Between 1847 and 1866, 211 ships brought 85,768 coolies to Cuba alone, of which 11,209 died on the crossing. How many died of illness and suicide shortly after their disembarkation is unknown. In any case, the Chinese have little hope of seeing their homeland again after landing. Anyone who is unable to pay the return trip after the expiry of their eight-year employment contract has only one option: to commit to another eight years, and so on. "

The Austrian explorer and later diplomat Karl von Scherzer , who took part in the Novara expedition between 1857 and 1859, noted in his book Journeys of the Austrian frigate Novara around the world about the pen trade (excerpts, abbreviated):

“Quite a few are stunned by alcohol or opium and only wake up in sealed depots. We have seen emaciated, gaunt, wretched figures pledge to work for $ 4 a year for some remote employer. The crossing, which usually takes four to five months, usually takes place on English, American, Portuguese, but unfortunately also a few German ships. Other reports speak out extremely favorably on the efforts of German missionaries to limit this human trafficking and in particular to prevent the so-called "Kulifang" (kidnapping). The agony the poor people are already exposed to during the crossing is evident from the fact that it is not uncommon for a number of these unfortunate people to jump overboard in order to put an end to their suffering by dying in the waves. According to statements from the captains of these slave ships, with whom we spoke in various ports, cases have occurred that 38 percent of the embarked Chinese died before they reached the port of arrival due to poor food and abuse. "

Representing the fate of many kidnapped Chinese is the statement made by a 23-year-old coolie on January 4, 1860 during the Fanny Kirchner affair :

“A group of coolie hunters, 13 in number, came into our house and caught me. I was bound, gagged and taken to Tung-poo, then to Tschengtschau to a junk , where I was asked if I wanted to emigrate. I was whipped with a rope for refusing to emigrate. Then I was taken to the Barracoons in Macau. I was told that if I answered no to the question of whether I wanted to leave the country on board the foreign ship, I would be brought back and killed. I was asked on board the foreign ship and I refused to leave. I was taken back to the Chinese junk and beaten again with the rope. I then said that I was ready to emigrate. Many others immediately said without being beaten again that they wanted to emigrate because the coolie hunters had threatened to kill the family otherwise. "

The travel writer Otto Ehrenfried Ehlers described his view of the pen trade from a different perspective in the magazine Im Osten Asiens in 1896 :

“It is well known that the first transport of Chinese coolies to East Africa left Singapore recently, and in a few days 600 Chinese who have been recruited as railroad workers for the Congo state are to be loaded in Macau.

One follows these ventures with great interest and is curious to hear whether employers and employees in the dark part of the world will find their way. The world agrees that the Chinese coolie as planter and earthworker, especially where he works in piecework, looks for his equals; the only question is whether it will not be too expensive for Africa. I do not know how much it cost to recruit and transport the coolies brought from Singapore to Pangani, but I do know that the cost of the head from Macau to any port on the German-East African coast is calculated at 450 marks against 240 marks to Sumatra . The contract would be for 3 years, 30 marks guaranteed earnings per month, free board and free return. The cost of the latter is assumed to be about 150 marks per head.

According to this, the costs for recruitment, travel there and back for the individual coolie would amount to around 600 marks, that is, 200 marks annually, equal to around 70 pfennigs for each working day. Adding the food (rice, tea and salted meat) to 30 pfennigs for man and day results in a total daily wage of 2 marks for the man, ie four times as much as the native in East Africa as a plantation worker up to now get cared for.

If, in spite of these high wages, the employment of Chinese coolies for the plantations turns out to be profitable, all that matters is to captivate the Chinese through correct, fair treatment. It will depend on the reports they send back home whether one can expect further immigration or not. "

aftermath

The Chinese coolies quickly gained a reputation overseas as hardworking and extremely frugal workers. Mark Twain stated in his book Roughing it , published in 1872 : "A messy Chinese man is rare and a lazy one does not exist". Nevertheless, the Chinese immigrants in almost all parts of the world were very soon exposed to hostility - above all from the white workers, who saw them as unpopular wage hunters and scabs. The result was discrimination and racist attacks, which sometimes ended in death.

Not only in South Africa organized white workers and employees in anti-Chinese associations to stop further immigration of coolies. The introduction of discriminatory laws in some countries, especially in the USA, where, among other things, the immigration of Chinese wives was not allowed, led to a wave of returns home as early as the end of the 19th century. The decision should not have been difficult for some coolies, as in many cases the women and children left behind waited longingly for them.

Despite the social exclusion, millions of coolies remained abroad because they could not afford the return trip or were looking for happiness by opening a restaurant, a laundry, a grocery store or the like. Social exclusion led to a policy of isolation and the formation of Chinese enclaves around the world , which found expression in Chinatowns and China townships . In contrast to classic immigrant quarters, these “Chinese cities” did not develop into transition stations, but instead assumed a permanent economic and sociological special position. Cantonese remained the leading language in all Chinatowns; Whenever possible, networks ( guanxi ) to the old homeland were established and maintained.

The diaspora and methods of the pen trade have a permanent place in the national memory of China. Human trafficking is still punishable by the death penalty throughout China, both in the People's Republic of China and in the Republic of China (Taiwan) (as of 2018). At the same time, the forced emigration of Chinese workers and the discussion about their overseas fate are important factors that contributed to the strengthening of Chinese nationalism . Numerous young overseas Chinese made a decisive contribution as activists to the political history of Chinese reunification . Sun Yat-sen referred to the Chinese community abroad as the "mother of the Chinese revolution " of 1911.

The global mobility of coolies was not only a factor in the development of national affiliation and worldwide networking. In Southeast Asian countries in particular, the Chinese presence has permanently changed social developments and disputes, which often continue to the present day. It is estimated that there are now 60 million Chinese living abroad. Over 75 percent of Singapore's residents are overseas Chinese; thus Singapore is de facto a Chinese state. About 30 percent of the population of Malaysia are Chinese. In other countries such as Indonesia, Myanmar, South Korea, Thailand or Vietnam, their share of the population is below ten percent. However, overseas Chinese dominate trade and industry in all states of Southeast Asia.

In no country in Southeast Asia are the descendants of coolies the target of outbreaks of violence at such regular intervals as in Indonesia. They are often the scapegoats for the collapse of the currency, the rapid rise in food prices, etc. With eight million, Indonesia has the largest Chinese minority worldwide. Although the overseas Chinese make up only four percent of the total population here, they control around 80 percent of all private wealth in Indonesia. In the Philippines, only one percent of the population are descendants of the Chinese immigrants, but here, too, large parts of the economy are in their hands. Ninety percent of all kidnapping victims in the Philippines are ethnic Chinese. In Malaysia, the government regularly passes laws that make it harder for the Chinese, who make up a third of the population, to do business. In contrast, in Thailand the 6.5 million Chinese are accepted as part of society and respected as business people. The situation is similar in South Korea.

Although the term coolie is seen as derogatory and racist in almost every country in the world today, the term is used unchanged, especially in Southeast Asia, the Caribbean and South Africa. This is not infrequently done intentionally in a derogatory context, but often carelessly in common parlance to refer to people of Indian or South Asian descent. The use of the word coolie is now banned in South Africa and Namibia as hate speech .

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ Berlin and Pomerania Evangelical Association for the Chinese Mission: Evangelical Reichsbote. Volume 23. Wiegandt and Grieben, 1873, p. 87.

- ↑ Jochen Kleining: Overseas Chinese between discrimination and economic success. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung eV, 2008, p. 1.

- ↑ Kluge. Etymological dictionary of the German language . Edited by Elmar Seebold , 25th edition, De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2011, keyword “Kuli 1 ”.

- ↑ Reinhard Sieder: Globalgeschichte 1800–2010. Böhlau Verlag, 2010, p. 102.

- ^ Sebastian Conrad: Globalization and Nation in the German Empire. CH Beck, 2010, p. 179.

- ↑ Jürgen Osterhammel : The transformation of the world: a story of the 19th century. CH Beck, Munich, 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-61481-1 , p. 246 ff.

- ↑ Berlin and Pomerania Evangelical Association for the Chinese Mission: Evangelical Reichsbote. Volume 23. Wiegandt and Grieben, 1873, p. 87.

- ^ Sebastian Conrad: Globalization and Nation in the German Empire. CH Beck, 2010, p. 211 f.

- ^ Peter Haberzettl, Roderich Ptak: Macau. Geography, history, economy and culture. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 1995, p. 10.

- ↑ Rolf-Harald Wippich: "... no respectable business". Oldenburg and the Chinese pen trade in the 19th century . In: Oldenburger Landesverein für Geschichte, Natur- und Heimatkunde (Hrsg.): Oldenburger Jahrbuch . tape 104 , 2004, ISBN 3-89995-143-3 , pp. 145–162 ( online [accessed January 5, 2017]).

- ^ Sebastian Conrad: Globalization and Nation in the German Empire. CH Beck, 2010, p. 184.

- ^ David M. Brownstone: The Chinese-American Heritage , New York, Oxford (FactsOnFile) 1988, ISBN 0-8160-1627-5

- ^ Gregory Yee Mark: Political, Economic and Racial Influences on America's First Drug Laws. University of California, Berkeley, 1978, p. 183.

- ^ Sebastian Conrad: Globalization and Nation in the German Empire. CH Beck, 2010, p. 179 f.

- ^ Sebastian Conrad: Globalization and Nation in the German Empire. CH Beck, 2010, p. 179 f.

- ^ Eberhard Panitz: Meeting point Banbury. Das Neue Berlin, 2003, p. 33 f.

- ↑ Berlin and Pomerania Evangelical Association for the Chinese Mission: Evangelical Reichsbote. Volume 23. Wiegandt and Grieben, 1873, p. 87.

- ^ Karl von Scherzer: Travels of the Austrian frigate Novara around the earth. KK Hof- und Staatsdruckerei Wien, 1861, p, 126.

- ^ Rolf-Harald Wippich: No respectable business. Oldenburg and the Chinese pen trade in the 19th century. in: Oldenhurger Jahrbuch 104, 2004, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Otto E. Ehlers: Kulihandel. in General Association for German Literature - Journal Im Osten Asiens , Berlin, 1896.

- ↑ Kaiping - The City of Strange Towers ; CRI, June 7, 2013 , accessed March 5, 2018

- ↑ Kaiping - The City of Strange Towers ; CRI, June 7, 2013 , accessed March 5, 2018

- ↑ Min Zhou : Chinatown. The Socioeconomic Potential of an Urban Enclave . Temple University Press Philadelphia, 1995, pp. 33 f.

- ^ Mechthild Leutner, Klaus Mühlhahn, Izabella Goikhman: Travels in Chinese past and present. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2008, p. 117.

- ^ Karl Waldkirch: Successful personnel management in China. Springer-Verlag, 2009, p. 35.

- ↑ Amy Chua: World on Fire. Doubleday Press, 2003, p. 61.

- ↑ Jochen Kleining: Overseas Chinese between discrimination and economic success. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung eV, 2008, p. 2.

- ↑ Jochen Kleining: Overseas Chinese between discrimination and economic success. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung eV, 2008, p. 1.

- ↑ The scapegoats are found ; Focus, February 21, 1998 , accessed March 5, 2018

- ^ Licensing and Livelihood: Railway Coolies ; Center for Civil Society , accessed March 5, 2018

- ↑ Act No. 4 of 2000: Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act. Updated to 2008 (PDF; 145 kB) accessed December 15, 2011