Curials

As Kurialien was referred to the 19th century, the titles, forms of address, and formal closing rates in formal letters. The term “curials” is derived from the expression “stylus curiae”, the writing style of the courts (“curia”) and their authorities.

The curials were part of the chancellery or court ceremony , which, among other things, determined the ranking of the parties and persons involved in government and official acts. In it they described the relationship of precedence in which the writer believed he was to the addressee.

regulate

The curials consisted of an extensive repertoire of titles and forms of address. Dealing with them was extremely delicate because they required detailed knowledge of the diplomatic ceremonies between the numerous sovereign states and sovereigns, the order of precedence of the estates and the official hierarchies of all government and administrative authorities in the empire . In addition, the fund of forms of address was constantly expanding and changing in an inflationary mode: As soon as a person was addressed by a higher-ranking person with a higher form of address than that to which they were entitled, other peers also raised a claim. Their application was difficult because there were only rough and no generally binding rules for them, so that in practice there was always the danger of committing a protocol error. Law firms were mainly guided by precedents collected in titular books.

The choice of salutation depended on whether and how far the person addressed was above or below the clerk in the ranking hierarchy. The writer was free to choose which rank to position the addressee as long as it was not chosen too low or too high. How high the addressee was classified between the permitted minimum and maximum depended on the difference in rank, the circumstances, the purpose and the urgency of the matter expressed in the letter. Women were always given a higher salutation than their class was entitled to.

In addition to the birth status, the functions of the addressees also had to be taken into account. For example, a baron was ranked higher in the rank of minister than a count without any noteworthy offices. How much offices upgraded their bearers was not specified. However, it had to be taken into account that an imperial minister, for example, was ranked above that of a royal or ducal minister.

Example: The Duke of Saxe-Weimar addressed the Prince of Kaunitz-Rietberg not with him zukommenden Title Durchlauchtig Highborn Prince , but with the higher Serene Tiger Prince , presumably because it is in the person addressed to the powerful Austrian chancellor Wenzel Anton von Kaunitz acted .

Letters with incorrect curials were returned to the sender's office. Often the return was made uncorrected and without comment, because the reason for a too low classification could not only have been a law firm error, but also a provocation.

title

Ruling sovereigns ( imperial princes , imperial counts , kings and the emperor ) placed their rulers' titles at the beginning in solemn letters . The title was followed by a greeting.

Example: By God's grace, [NN], Bishop of Speyer , Provost of Weissenburg and Odenheim , of H. Röm. Imperial Prince. Our gracious greetings beforehand,

The design of the greeting depended on the rank of the addressee. If the recipient was also a prince, the greeting could be: Our friendly services, and what else we can do more dearly and good, beforehand. This was followed by the salutation.

The emperors and kings used the title of ruler in chancellery letters to people of equal and lower rank, the other imperial princes only to non-sovereign persons and corporations. Only the emperors and kings were allowed to put the pronoun 'we' in front of the title.

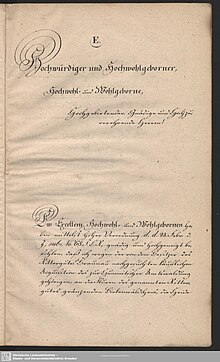

Salutation

Each letter was introduced with a salutation. The addressees were addressed with their highest title, if necessary, but in any case with at least one word of honor . In contrast to the titles, there was no legal claim to them. Nevertheless, they were at least as important in their application. Depending on the recipient's rank, a space of at least three fingers was added below. In letters to the emperor, this distance could be two hand widths.

Frequently used words of honor were: dear, honored, honored, honorable, venerable (for parents), strict, vester, nobler, nobler, nobler, nobly born, venerable, well-honored, well-ordained (for civil servants), highly ordained (for higher civil servants), graciously, gnädigster, Rev. (for higher Sacred) hochwürdigster (for bishops), hochzuehrender, hochzuverehrender, wohlgelarter (for academics without Doctoral) hochgelarter (for doctors), high noble-born, well-born, high and well-born, high well-born , high-born , durchlauchtig high-born, serene, serene, most serene, most powerful and most insurmountable (for the emperor). They could be increased by adding such as especially , especially , most , much , high and very .

The salutation love / r ... was only used in relation to low-ranking people and signified a disparagement when it was not used by close friends or ruling princes. The salutation Mr. was generally used by lower ranks compared to higher ranks. For particularly high-ranking personalities, such as high aristocrats in high offices or princes, the salutation Mr. could be doubled (Most Serene Elector and Most Gracious Lord, Lord) . An addressee could be devalued by combining the salutation with the surname of the person addressed ( Most Valuable Privy Councilor NN instead of Most Valuable Privy Council ). The smaller the ranking difference between the writer and the recipient, the higher the recipient's rating above the minimum.

Examples:

- For princes, the salutation high-born prince was considered the minimum level . It was used by kings and electors. Bourgeois princes mostly addressed them with the title Most Serene Prince .

- Barons were addressed by princes at the minimum level of well-born barons . Counts used the lower salutation High Born Baron , while commoners used the salutation High Born Baron . (The salutation serene would have exceeded the maximum for barons, because it was exclusively reserved for princes.)

- An example of a particularly carefully elaborated form of address in a letter from the Franconian Circle to the Reich Chamber of Commerce illustrates the excessive complexity of the curials when a letter is addressed to several people of different rank:

"To those well-bored and well-drilled, noble, vesten and well-learned, then well-drilled, well-drilled and well-drilled, respectively your Roman. Imperial and Royal Catholic Majesty decreed proper secret councilors, then the laudable Imperial and Imperial Chamber Court of Wetzlar, highly appointed Chamber judges, presidents, and assessors of our particularly dear gentlemen and dear special, then most highly respected, respectively, friendly, well-loved and honored cousins, then and honored, as well as furthermore, especially highly inclined and honored gentlemen. "

In the sphere of the sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire, the salutation curials reflected the complexity of the political situation. The slightest deviation from the usual formulas could lead to serious upsets.

Examples:

- If a ruling Count holder of a fief was focused on the territory of princes was, he was by the latter as a vassal treated and therefore not as high-born Count , but with the lower form of address Excellency born Graf addressed.

- Protestants refused to address cardinals as eminence .

- The Kaiser addressed the King of Prussia with:

"We, [name and title] offer the most noble, powerful prince, Lord [name], King of Prussia, etc. to our especially dear friends, uncle and brother, our uncle-friend and brotherly will, love and all the best.

Loudest, most powerful prince, especially dear friend, uncle and brother. "

In the context, the king was named by the emperor your love (the address of princes for princes of the same and lower rank). The phrase especially prefer (instead of prefer ) was reserved for the King of Prussia.

- The King of Prussia replied to the Emperor:

“Your Imperial Majesty is our particularly friendly service, and whatever else we can do much more dearly and good, at any time beforehand.

Particularly friendly, well-loved Mr. cousin and brother! "

The forms of address brother , aunt , cousin , uncle and nephew , when used by princes, did not refer to relationships of family members, but to relationships of rank: brother usually denoted equality, the others more or less great differences in rank. Furthermore, the forms of address Dear Friend and Dear Neighbor were common in political correspondence . Accordingly, friendly cousins , friendly neighborly etc. services were offered in the salutation sentences .

- The state book by Christian Lünig and Wilhelm Ludwig Wirth distinguished between 141 forms of address for the most important cities in the empire. The magistrate of the royal city of Salzburg had to be addressed by the bourgeoisie as follows:

"To the noble, stern, vests, prudent and wise gentlemen city syndicates, mayors and councilors of Salzburg, etc."

The city of Kassel , also the residence of an imperial prince, was entitled to the following address:

"To those high and well-noble, forts and well-educated, also well-honored vests, great respectable, prudent, high and well-wise Lord Mayors and Council of the Princely Hessian Residentz and fortress Cassel etc."

In order to avoid salutation curials, letters were often introduced in French in the 18th century. Instead of using the solemn chancellery writing, regents could resort to the more informal and at the same time more personal form of cabinet writing or handwriting.

Contextual address

With some titles and honors the right to lead a was Salutation title as Majesty , Highness , Excellency , etc. connected. In all other cases, special context forms of address were used, which were based on the form selected in the form of address.

Frequently used contextual addresses were: Your high noble, your well-born, your high-born, your (noble / princely / high-princely) graces, your / your lover, your Excellency, your (electoral / ducal) serenity, your devotion, your eminence, your (imperial / Royal) Highness , Your (Imperial and Royal / Imperial / Royal) Majesty.

You or hers were only allowed in high and very high ranking people. You were allowed under the Count matter since the 17th century, only the emperor, kings and electors to persons. In order to avoid repetition of contextual salutations , terms such as the same , the same , the same or the very highest have been used.

The curial style required the addressee to exalt, but the writer to belittle himself. Justus Claproth wrote about this in 1769: "The most humble expressions must be used and everything must be sought out that can flatter the superiors in only one way;" The recipient acted out of grace and grace; the scribes acted with reverence, obedience, devotion, and respect. For the same reason, sentences could not begin with I. For example, a request was made humbly to those of higher rank, obedient to peers and devoted to subordinates . Other frequently used expressions that described the actions of addressees were: gracious (st), most gracious, mildest, fairest, highly gifted (tes) t, inclined (tes) t, generous, favorable . Here had a form be chosen that matched the used in the salutation of honor words: At a allerdurchlauchtigste person you wrote humbly or allerdemütigst but a gracious person submissive or humble . The correct use of curials thus forced a characteristic style of language called the chancellery style . They were only applied to be correct if they were embedded in phrases like: graciously kipper Your Excellency deign / in listening ... , your worship is annoch in unentfallenem inclined keepsake ... or have your Majesty graciously deigned to prescribe ... .

Courtoisie, final compliment

The end of a formal letter contained an offer of service, congratulations, a request for further favor, a mercy insurance and the like. Often it was added by the sender in a fair copy made out by a registrar.

Expressions often used in the closing formulas were: most submissive, most obedient (to the emperor), humble, willing to serve, devoted to service, willing to serve, obedient, submissive, obediently submissive, loyal obedience, binding, loyal, devoted, loyal, devoted, pleading, pleading, obliging , due, due, legally. Most of these expressions could be increased: humble , willing , etc.

Examples:

- In letters to citizens of the same rank, for example, signed with: Your well-born, most obedient / most devoted / willing friend and servant

- In letters to counts, princes signed: the count's friendly friend , barons and untitled aristocrats: Your highborn most devoted , servants and subjects of the count: Your most subservient to the counts

- The emperor wrote to lower-ranking subjects: ... and remain in favor of you with imperial grace.

- In letters from subjects to princes the typical phrase was: ... and by the way, I sigh to die in the pit at the very highest imperial feet / in the electoral graces.

Women signed with willing or devoted to honorary service and replaced submissive with humble . Sovereigns included their rulers' titles in the final compliment of their peers.

Criticism and abolition

From around the middle of the 18th century, the critical public and parts of the civil servants quickly understood the curials. At the same time, they were increasingly the subject of fierce and polemical criticism. The sharpest critics included prominent representatives of the cultural life of the Enlightenment such as Christoph Adelung , Joseph von Sonnenfels and Leopold Friedrich Günther von Goeckingk . Friedrich Struensee succeeded in abolishing the curials for the first time in Denmark in 1771 . Since 1779, the great title of king was no longer used in Prussia, even in solemn documents. In the Habsburg Monarchy , Joseph II abolished the curials in their previous form in 1782 and replaced them with reduced and simplified forms of address. In Prussia, a joint initiative by Friedrich Wilhelm III failed in 1800 . and Karl Augusts von Hardenberg to simplify the curial style at the resistance of the State Council . It was not until 1810 that the curials were also abolished in Prussia. The reason stated:

“ We want the Curial style, which has been retained up to now, which is nothing other than the style of common life of bygone times, [...], to be consistently abolished and by every authority in the current style of common life, both to superiors and to written and decreed to the authorities and persons who are at the same level and subordinate to them, as happens in most other states, without forgiving the least of the authority. [...] The administrative and judgmental authorities must know how to provide obedience and respect through the spirit that rules them, through their way of acting and, if necessary, through the means at their disposal, not through outdated, empty forms. "

In practice, the old curial style persisted for many years both in the Habsburg monarchy and in Prussia.

literature

- Christian August Beck: An attempt at state practice, or Canzeley exercise, from politics, state and international law . Vienna 1754.

- Peter Becker: "... how little the reform swept away the old leaven." On the reform of the administrative language in the late 18th century from a comparative perspective . In: Hans Erich Bödeker, Martin Gierl (Hrsg.): Beyond the discourses. Enlightenment Practice and the World of Institutions from a European Comparative Perspective . In: Publications of the Max Planck Institute for History , No. 224. Göttingen 2007, pp. 69–97.

- Johann Nicolaus Bischoff: Handbook of the German Cantzley practice for prospective state officials and businessmen. 1. Part, of the general characteristics of the Canzley style . Helmstedt 1793.

- Johann Alphons De Lugo: Systematic manual for everyone who has to design business essays, Vol. 1 for private individuals . 3rd edition, Vienna 1784.

- Leopold Friedrich Günther von Goeckingk: About the office style . In: Deutsches Museum , 1, 1776, pp. 207–245.

- Hermann Granier: An attempt to reform the Prussian chancellery style in 1800 . In: Research on Brandenburg and Prussian History , 15, 1902, pp. 168–180.

- Martin Haß: About the filing system and the chancellery style in old Prussia . In: Research on Brandenburg and Prussian History , 20, 1910, pp. 201–255.

- Eckhart Henning: Salutations and title . In: Friedrich Beck, Eckhart Henning (Hrsg.): The archival sources. With an introduction to the historical auxiliary sciences . 3rd edition Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2003, pp. 231–244.

- Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi: Instructions on a good German writing style and all written elaborations that arise in business and legal matters, [...] . Vienna 1774.

- Johann Christian Lünig: Theatrum ceremoniale historico-politicum or historical and political scene of the European Kantzley ceremony [...] . Leipzig 1720.

- Johann Christian Lünig / Wilhelm Ludwig Wirth: Newly opened European state titular book […] . Leipzig 1737.

- Klaus Margreiter: The office ceremonial and the good taste . Administrative language criticism 1749–1839. In: Historische Zeitschrift , 297 (2013), pp. 657–688.

- Friedrich Carl von Moser: News from old canzley and court form books, as a contribution to the history of the canzeley ceremony . In: Friedrich Carl Mosers Kleine Schriften, to explain the state and Völcker law, as well as the court and Canzley ceremonies . Frankfurt am Main 1752, Volume 3, pp. 395-440.

- Friedrich Carl von Moser: Attempting a State Grammatic . Frankfurt am Main 1749.

- Adolf Nitsch: Practical instruction on the German business and curial styles in general, and in application to forestry in particular . Dresden / Leipzig 1827.

- Johann Stephan Pütter: Instructions for legal practice: how in Germany both judicial and extrajudicial legal transactions or other Canzley, Reich and state matters are negotiated in writing or orally, and enclosed in archives . Goettingen 1765.

- Franz X. Samuel Riedel: The Viennese secretary on everyday cases for common life . 11th edition, Vienna 1812.

- Johann Daniel Friedrich Rumpf: The Prussian State Secretary. A handbook for the knowledge of the business circles of the higher state authorities, combined with practical instructions for the written presentation of thoughts in general, as well as for the business and letter style and other articles of common life in particular, together with the instruction on the titulatures and a list of the knights of the Prussian eagle Medals . 2nd edition, Berlin 1811.

- Georg Scheidlein : Explanations about the business style in the Austrian hereditary lands . Vienna 1794.

- Joseph von Sonnenfels: About the business style . 2nd edition, Vienna 1785.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Adolf Nitsch: Practical instruction on German business and curial styles in general, and in application to forestry in particular . Dresden / Leipzig 1827, p. 14. p. 213.

- ↑ Curials. In: Johann Heinrich Zedler : Large complete universal lexicon of all sciences and arts . Volume 6, Leipzig 1733, column 1872.

- ↑ Johann Christian Lünig: Theatrum ceremoniale historico-politicum or historical and political scene of the European Kantzley ceremony… . Leipzig 1720. p. 40.

- ↑ Johann Stephan Pütter : Instructions for legal practice ... 1st part . 3. Edition. Göttingen 1765, p. 37 ( digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Lünig: Theatrum ceremoniale . Pp. 2-23.

- ↑ Franz X. Samuel Riedel: The Viennese secretary on everyday cases for common life . 11th edition. Vienna 1812. p. 186 ( digitized in the Google book search)

- ↑ Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi : Instructions on a good German writing style and all written elaborations occurring in business and legal matters…. Leipzig 1755, p. 185.

- ^ Johann Nicolaus Bischoff: Handbook of the German Cantzley practice for prospective state officials and businessmen. 1st part . Helmstedt 1793. ( Digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Johann Alphons De Lugo: Systematic manual for everyone who has to draft business essays, Volume 1 for private individuals . 3rd edition, Vienna 1784, p. 259.

- ↑ Friedrich Carl von Moser : Treatise on the punishment of erroneous and indecent writing, after the use of the courtyards and Canzleyen . Frankfurt am Main 1750, pp. 9-13. ( Digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 382.

- ^ Lünig: Theatrum ceremoniale . P. 206.

- ^ Lünig: Theatrum ceremoniale . Pp. 42-196.

- ^ Friedrich Carl von Moser: Attempt at a state grammatic. Frankfurt am Main 1749, p. 199 ( digitized in the Google book search)

- ↑ a b Bischoff: Handbook . P. 426.

- ^ De Lugo: Handbook . P. 260.

- ^ Justi: Instructions . P. 185.

- ^ Pütter: Instructions . P. 22.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 407.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 378.

- ^ Lünig: Theatrum ceremoniale, p. 42 f.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 428.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 396.

- ^ Johann Christian Lünig, Wilhelm Ludwig Wirth: Newly opened European state titular book [...] . Leipzig 1737, p. 508. ( Digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Lünig, Wirth: Staats-Titular-Buch . P. 491.

- ^ Johann Stephan Pütter: Recommendation of a sensible new fashion Teutscher inscriptions on Teutschen letters . 2nd edition, Göttingen 1784, p. 9 f ( digitized in the Google book search)

- ↑ Christian August Beck: Attempt at state practice, or Canzeley exercise, from politics, state and international law . Vienna 1754. pp. 36–45. ( Digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . Pp. 443-450.

- ^ Moser: Staats-Grammatic . Pp. 202-210.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . Pp. 453-455.

- ^ Justus Claproth: Principles I. of the production and acceptance of invoices; II. Of writings and reports; III. Of memoranda and resolutions; IV. From the establishment and maintenance of their court and other registries . 2nd edition, Göttingen 1769, p. 101 ( digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Justi: Instructions . P. 183.

- ↑ Adolf Nitsch: Practical instruction on German business and curial styles in general, and in application to forestry in particular . Dresden / Leipzig 1827, p. 14.

- ^ Justi: Instructions . P. 184.

- ^ Pütter: Instructions . P. 47.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 466.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 457 f.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 470 f.

- ^ Bischoff: Handbook . P. 465.

- ↑ Klaus Margreiter: The office ceremonial and the good taste . Administrative language criticism 1749–1839. In: Historische Zeitschrift , 297, 2013, pp. 657–688.

- ↑ Peter Becker: "... how little the reform swept away the old leaven." On the reform of the administrative language in the late 18th century from a comparative perspective . In: Hans Erich Bödeker, Martin Gierl (Hrsg.): Beyond the discourses. Enlightenment Practice and the World of Institutions from a European Comparative Perspective . In: Publications of the Max Planck Institute for History , No. 224, pp. 69–97. Göttingen 2007.

- ^ Johann Christoph Adelung: About the office style . In: Magazine for the German language . Vol. 2. Leipzig 1783/84, pp. 127-142.

- ↑ Joseph von Sonnenfels. About the business style . Vienna 1784. ( digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Leopold Friedrich Günther von Goeckingk: About the office style . Deutsches Museum 1 (1776). Pp. 207-245.

- ↑ Anonymous: Something else about the office style . In: Deutsches Museum , 1779, 2nd vol. P. 521 f.

- ↑ Martin Haß: About the filing system and the chancellery style in old Prussia . In: Research on Brandenburg and Prussian History , 20, 1910, p. 227.

- ^ Riedel: The Viennese secretary . Pp. 174-187.

- ↑ Hatred: Filing . Pp. 227-230.

- ↑ Lorenz Beck: Distribution of business, processing steps and file style forms in the Kurmärkische and in the Neumärkischen war and domain chambers before the reform (1786-1806 / 08) . In: Friedrich Beck, Klaus Neitmann (Hrsg.): Brandenburg State History and Archive Studies . Weimar u. a. 1997, pp. 417-438.

- ^ Johann Daniel Friedrich Rumpf : The Prussian State Secretary. [...] . 2nd edition, Berlin 1811. p. 144 ( digitized in the Google book search)

- ^ Johann Daniel Friedrich Rumpf: The business style in official and private lectures, based on the art of thinking correctly and expressing oneself clearly, firmly and beautifully; with instructive examples for self-teaching . Reutlingen 1822, pp. 156-165. ( Digitized in the Google book search)

- ↑ Georg Scheidlein: Explanations about the business style in the Austrian hereditary lands . Vienna 1794. p. 72.