Lake Loppio

|

Lake Loppio Lake of S. Andrea |

||

|---|---|---|

|

||

| The resurfaced lake in 2013 | ||

| Geographical location | Garda mountains | |

| Drain | Rio Cameras → Etsch | |

| Data | ||

| Coordinates | 45 ° 51 '52 " N , 10 ° 55' 12" E | |

|

|

||

| Altitude above sea level | 220 m slm | |

| surface | 60 ha | |

| length | 1.87 km | |

| width | 480 m | |

| Maximum depth | 4 m | |

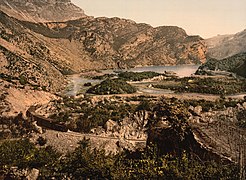

The Lago di Loppio , formerly known as Lago di S. Andrea called, is a silted lake in Valle del Cameras in the province of Trento , the partially filled only after prolonged periods of rain again. It is located between the Adige Valley and Lake Garda, west of Loppio , a fraction of the municipality of Mori, and east of Nago below the Passo San Giovanni . It is bordered in the north by the southern foothills of the Monte Bondone - StivoGroup and to the south by the northern foothills of the Monte Baldo group.

On the northwest side below the pass, the bank is very rugged with several peninsulas and bays. This area is known as the Dossi di Nago . Due to the low water level, reed plants such as water lilies and reeds were native here. On the west side in the middle of the lake is the island of Sant'Andrea , once the largest of the six islands of the Loppio Lake, named after a small church consecrated to St. Andrew , of which only ruins have been preserved. The other five hilly and partly very small islands, the Isola dei Gamberi , Isola del Carezzer , Isola del Salgaro , Isola La Cuccina and L'Isoleta , were all in the area of the Dossi di Nago.

The lake was fed by a few smaller springs on the south-east bank at the foothills of Monte Altissimo di Nago . The drain was formed by the Rio Cameras, which flowed off in the direction of the Adige . Until the beginning of the 19th century, the Lago di Loppio extended to the place Loppio.

While the north bank is completely untouched, the busy Strada statale SS 240 Loppio – Val di Ledro lies on the south bank . There is also a cycle path between the state road and the lakeshore, which branches off the Etsch cycle path at Mori and leads to Lake Garda.

Emergence

Loppiosee was created by damming spring water behind the alluvial cone washed up by the Rio Gresta in the southeast of the lake . Previously, after a side branch of the Adige Glacier had retreated in the northwest at Passo San Giovanni , a landslide had blocked the valley and thus prevented the outflow of water towards Nago and Lake Garda. The Dossi del Nago were also created in this way.

history

Until 1953

Due to its location between the Adige Valley and Lake Garda, the lake has always been of a certain strategic importance. This is also evidenced by the numerous archaeological finds on the island of Sant'Andrea, which were found during excavations from the end of the 1980s in several excavation periods and which go back to the late Roman era and cover a period extending over several centuries.

In 1439 a Venetian fleet passed the lake on its way from the Adige Valley to Lake Garda. With this company, known as Galeas per montes , the Republic of Venice was able to expand its sphere of influence to include the whole of Lake Garda.

At the beginning of the 16th century, after the end of the Venetian era under Maximilian I , the Loppiosee was divided between the Counts of Arco , as feudal lords of Castel Penede , and the Counts of Castelbarco . The west bank with the Dossi di Nago fell to the Arcos, which later became the property of the municipality of Nago-Torbole , while most of the lake fell under the control of the Castelbarco. Until the end of the 19th century, this division and the resulting use repeatedly caused disputes between the parties, which also went through the courts in several instances.

In 1820 a seven meter wide and two meter deep drainage channel was built to regulate the water level of the lake, as it was subject to strong fluctuations and at times flooded the surrounding arable land. With the construction of this canal, the area between today's lake bed and the town of Loppio was finally drained and used for agriculture. The canal was also used to regulate the drain, the Rio Cameras, which was led underground to Loppio over a length of 500 meters. At the beginning of this drainage tunnel, where the drainage channel ended, a basin was built for fishing, which represented an important additional source of income. In the second half of the 19th century, parts of its rugged northwest side were also drained, which were then used for agricultural purposes.

In addition to fishing, around 10 species were found in Lake Loppio, including tench , perch and eel , until the advent of modern refrigerators, knocking out ice blocks for cooling was an important extra income in winter. In contrast to Lake Garda, Lake Loppio usually froze from December to February too. The ice reached a thickness of up to 50 cm. The Mori – Arco – Riva local railway , which went into operation in 1891, was also used to transport the blocks of ice . Its route led past the southern shore of the lake.

During the First World War , the lake was initially between the fronts. In January 1916, Alpini of the Val d'Adige battalion were able to occupy the island of Sant'Andrea for some time and set up a number of preferred positions there. Two memorial plaques that were left there by the Italian troops testify to this today.

In 1927 Gabriele d'Annunzio caused a stir when he landed on the lake in his seaplane to visit his friend Count Pier Filippo Castelbarco.

With the demographic increase after the First World War, the demand for arable land also increased. In 1930, in line with the so-called Battaglia del Grano proclaimed by Mussolini , a project to drain the lake was commissioned by the Castelbarcos for this purpose, which, however, did not go beyond the project status due to a lack of financial resources.

Only nine years later there was a new project, which envisaged the construction of a tunnel between the Adige and Lake Garda, with which the water of the Adige was to be channeled into Lake Garda during floods and thus to prevent flooding in the lower reaches of the river. The project envisaged that this 10 km long tunnel should cross the Loppiosee about 20 m below the lake bed in its middle. Work on the Etsch-Gardasee tunnel began in Torbole in 1939, but was discontinued in 1943 due to the Second World War . At this point in time, the tunnel was just over two kilometers in length and one kilometer from Lake Loppio.

From 1953

After the resumption of work in 1953, there was loud discussion about the safety of the tunnel workers, as there was fear of water ingress in the area of Lake Loppio. But there were also critical voices who claimed that this security question was only brought forward so that the lake could be drained without much discussion, in order to gain additional agriculturally usable areas, as had already been attempted in the past. At the same time, the future operator of the hydropower plant in Torbole speculated that the lake would be used as a collecting basin, next to the Lago di Cavedine with which the Loppiosee should be connected. For this purpose, a dam was to be built at the level of the island of S. Andrea, and the water between the dam and the Passo San Giovanni should be dammed. In this sense, too, prior pumping would have been an advantage. On April 3, 1956, two large pumps began to pump out the water from Lake Loppio in the Rio Cameras. The pumping also had unpredictable negative side effects, so several springs that were used for the drinking water supply in Nago and Mori began to dry up, probably due to the lack of pressure exerted by the lake. In September 1956 the lake had disappeared except for a small remnant in the middle of the lake, where the fish collected, which became easy prey for the numerous onlookers who came by.

With the tunnel work, a supply tunnel was built at the level of the island of S. Andrea, which also served for ventilation during the construction work. The inflow of the springs that fed the lake was cut off when the tunnel was being driven forward, and the water seeping through between the rock and tunnel walls was drained away with the help of a drainage tunnel under the actual main tunnel. This runoff, which is dependent on precipitation and normally averages around 400 to 600 l / s, continues to pour into Lake Garda at the tunnel exit in Torbole.

At the beginning of December 1958, the two halves of the Etsch-Gardasee tunnel driven by Torbole and Mori broke through. This reignited the discussion about the future of Lake Loppio and the two obviously contradicting projects, use as arable land or as water storage. Both projects came to nothing in the course of the 1960s. Using it as a storage facility faced technical and economic problems. So sealing would only have been possible with great effort and would probably not have been in proportion to the expected benefit. The disaster on the Vajont in 1963 had also raised awareness of the use of hydropower. With increasing industrialization, however, the interest in additional agricultural land began to decline, so that use in this sense no longer seemed appropriate.

As a result, all economic interest in the former Loppio Lake was lost and the lake bed slowly began to grow over. The Loppiosee only fills up again after longer periods of rain, sometimes for longer periods of time, from 1975 to 1980, so that even fish were released again. When the lake filled with water again in 2001, there was a massive migration of common toads , for which the lake is used as a spawning ground , and which also impaired traffic on the state road. As a result, barriers and tunnels were built to pass the toads under the road.

Nature reserve

Since the 1960s there have been several initiatives to recreate the lake. In 1990 the responsible local council of Mori also approved such a project. As early as the 1980s, the provincial government met the legal requirements for the establishment of a nature reserve and the province acquired the site of the former lake from the Castelbarco family. With the takeover of the Etsch-Gardaseetunnel, whose responsibility was transferred to the Autonomous Province of Trento in 2000, and the need to rehabilitate the tunnel, the opportunity arose to work out a project to restore the lake. One such was finally presented in 2007. This project envisaged tapping a water vein under the foothills of Monte Altissimo on the southeast side of the lake and channeling the water into the lake through an 850 meter long tunnel in order to at least partially fill the lake again.

The execution of the project was postponed for various reasons and had to be changed several times. The first phase of the project was completed in summer 2012. It already became apparent that the amount of water tapped was insufficient for the implementation of the project, especially since it turned out in retrospect that the water vein is fed exclusively by precipitation and does not provide any water during prolonged drought. As a result, the second project section, which required the requalification of the bank area, was not carried out any further.

Flora and fauna

With its approximately 112 hectares, the Lago di Loppio is the largest protected wetland in Trentino. On the former lake bed, wet and marsh meadows with numerous white willows have spread. In some places on the bank area, peat banks have formed and rare sour grass plants have settled. The nature reserve also includes habitats for large sedge beds , for alder swamps and gray willow bushes (Alnetea glutinosae) as well as reeds . It is also home to several types of orchids .

In the periods when the lake is filled with water, it serves as a resting and breeding place for numerous water birds. A total of 52 species were identified throughout the year. Among the species that breed on the lake partly depending on water levels, include little grebe , mallard , moorhen , coot , Sandpiper , Black Kite , Common Buzzard , Hoopoe , wagtail , tit , blackbird , sedge warbler , red-backed shrike , carrion crow , raven and Chaffinch .

Besides birds are also found in the nature reserve amphibians including the common newt , the yellow-bellied toad and the frog and various reptiles such as the Eastern green lizard , wall lizard , yellow-green whip snake , Aesculapian , slow worm , grass snake , dice snake and asp . But deer , badgers and chamois can also be found.

literature

- Associazione Culturale Loppio (ed.): Loppio… il passaggio di un'epoca , La Grafica, Mori 2009.

- Giovanni Berti: Il Lago di Loppio, alcune vicende storiche e la sua misteriosa scomparsa in: Gruppo Culturale di Nago-Torbole (ed.): La Giurisdizione di Pénede. Quaderno periodico di ricerca storica , year XXV - No. 48 June 2017, Arco 2017. ISSN 2284-0214

- Barbara Maurino: Il sito archeologico di Loppio Sant'Andrea , Fondazione Museo Civico Rovereto, Rovereto, 2012.

- Giuseppe Ratti: La bonifica del Lago di Loppio: saggio economico-agrario , Tridentum, Trento 1930.

- Gino Tomasi: I trecento laghi del Trentino , Artimedia-Temi, Trento 2004 ISBN 88-85114-83-0

- Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Servizio parchi e foreste demaniali (ed.): Progetto per la tutela e la valorizzazione del biotopo di interest provinciale "Lago di Loppio" , Trento 1994.

Web links

- Vittorio Christofori: La Galleria Adige-Garda ed il Lago di Loppio. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019 ; accessed on September 5, 2017 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Giovanni Berti: Il Lago di Loppio, alcune vicende storiche e la sua misteriosa scomparsa pp. 7–8

- ↑ Gino Tomasi: I trecento Laghi del Trentino S. 342

- ^ Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Servizio parchi e foreste demaniali (ed.): Progetto per la tutela e la valorizzazione del biotopo di interest provinciale "Lago di Loppio" pp. 15-16

- ^ The S. Andrea-Loppio excavation site in Italian , accessed on September 6, 2017.

- ^ Giovanni Berti: Il Lago di Loppio, alcune vicende storiche e la sua misteriosa scomparsa, pp. 14-20

- ^ Associazione Culturale Loppio (ed.): Loppio ... il passaggio di un'epoca pp. 47-60

- ^ Associazione Culturale Loppio (ed.): Loppio ... il passaggio di un'epoca p. 65

- ^ Giovanni Berti: Il Lago di Loppio, alcune vicende storiche e la sua misteriosa scomparsa p. 23

- ^ Giovanni Berti: Il Lago di Loppio, alcune vicende storiche e la sua misteriosa scomparsa pp. 25-30

- ^ Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Servizio parchi e foreste demaniali (ed.): Progetto per la tutela e la valorizzazione del biotopo di interest provinciale "Lago di Loppio" p. 28

- ^ Giovanni Berti: Il Lago di Loppio, alcune vicende storiche e la sua misteriosa scomparsa, pp. 30–31

- ^ Associazione Culturale Loppio (ed.): Loppio ... il passaggio di un'epoca pp. 78-81

- ↑ Project Loppiosee Article from March 7, 2012 in Italian ( Memento of the original from September 7, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , accessed September 6, 2017.

- ↑ Parliamentary question in the state parliament of the Autonomous Province of Trento on the future of Lake Loppios on June 22, 2017 in Italian , accessed on September 6, 2017.

- ↑ Biotop Lago di Loppio in Italian , accessed on September 6, 2017.

- ^ Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Servizio parchi e foreste demaniali (ed.): Progetto per la tutela e la valorizzazione del biotopo di interest provinciale "Lago di Loppio" pp. 77–80