Aesculapian snake

| Aesculapian snake | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Aesculapian snake ( Zamenis longissimus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Zamenis longissimus | ||||||||||||

| ( Laurenti , 1768) |

The Aesculapian snake ( Zamenis longissimus , Syn . : Elaphe longissima ) belongs to the snake family (Colubridae) and, with a length of up to two meters, is one of the largest snake species in Europe. Like most species in this family, it is non-toxic.

features

The Aesculapian snake reaches an average body length of 1.40 to 1.60 meters, but can also be up to two meters long and is strongly built. Males are generally slightly larger than females.

The basic color of the snake ranges from yellowish brown to olive green and gray-brown to gray-black, with the surface being smooth and shiny. Many of the scales are outlined in white, creating light vertical stripes along the body. In some animals there is also a dark vertical stripe along the sides of the body. The belly is light or greenish yellow to whitish in color. In very dark individuals, however, the underside of the body can also be colored blue-black. While the 23 (less often 21) rows of back and side scales are smooth, the belly scales have light keels that make climbing easier.

The head is only slightly separated from the trunk and normally has no drawing. A dark temple band can be formed above the eyes and extends back to the neck. The eyes are medium-sized with a round pupil . The head has eight, more rarely nine, upper lip shields or supralabials as well as a forehead shield, which in herpetology is called praeoculare .

The young animals are markedly more conspicuous. They have a light basic color with dark spots on the back as well as a distinct dark transverse band over the muzzle and a backward V-mark on the neck. There is also a dark band on the temples and behind it on both sides a light yellow spot. These spots can lead to confusion with the grass snake ( Natrix natrix ), where these spots are typical.

distribution and habitat

The distribution of the Aesculapian snake is Mediterranean and is therefore concentrated in southern Europe and Asia Minor ; however, there are also isolated occurrences in Germany , Austria and Switzerland , which represent parts of the northern limit of distribution. There are relic occurrences in Germany in the Rheingau in the vicinity of Schlangenbad and in the Sommerberg nature reserve near Frauenstein , the southern Odenwald , on the Danube near Passau and the lower Salzach . In Austria all federal states are settled with the exception of Vorarlberg and Tyrol .

In the Passau area, the occurrence on the banks of the Danube has been known for a long time. Beyond this core area, numerous other occurrences have been detected, including at Jahrdorf , which is about seven kilometers as the crow flies from the Danube. West of the Ilz , there was only one proof at Haslachhof. At the lower Inn there are several well-known occurrences on the Bavarian side, for example in the Passau urban area, Neuburg am Inn , Vornbach , Niederschärding and Neuhaus am Inn .

The occurrences in the Wiesental (southern Black Forest) mentioned again and again in the literature could not be proven until today and are very doubtful.

In summer 2019, a larger population of Aesculapian snakes was reported in the Odenwald.

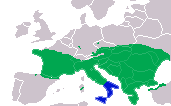

The distribution area accordingly extends from northern Spain through central France , Switzerland, Austria and some relict areas in southern Germany via the Czech Republic , southern Poland and the Balkan states to Greece and the southwestern areas of the former Soviet Union and further to Turkey , the Transcaucasus and the northern Iran . The slightly lighter animals in central and southern Italy as well as in Sicily were contrasted with the nominate form Zamenis longissimus longissimus as a subspecies Zamenis longissimus romana until recently ; Today, due to protein electrophoretic studies and sequence differences in the mitochondrial DNA, they are regarded as a separate species under the name of the Italian Aesculapian snake ( Zamenis lineatus ).

The Aesculapian snake prefers warm and sunny areas, which, however, must not be too dry. The snakes are found mainly in warm, humid, sun-exposed places in the flatlands and on sunny slopes in the mountains. It is often found on the banks of water and in alluvial forests as well as in clearings or in rubble and bushes with ivy and brambles . Stone walls, old quarries, ruined areas and the edge areas of agricultural areas such as bushy hillside meadows are also popular. The highest occurrences are at around 1500 to 2000 meters, but mostly lives below 1000 meters.

Way of life

The Aesculapian snake is diurnal, but shifts its main phases of activity to dawn and dusk, especially in midsummer. When it is very hot, it hides in the shade. In the winter months, the adder hides and, depending on the climate, hibernates for five to six months .

The Aesculapian snake can climb very well by spreading its scales; she can even cope with upright trees. Nevertheless, it lives mainly on the ground and in low undergrowth and climbs especially when looking for food. She moves very quickly and quietly. Even in the event of disturbances, the snake is not very aggressive.

Diet and predators

The Aesculapian snake feeds on small mammals , especially mice , as well as on lizards and birds and their nestlings and eggs. In particular, species of long-tailed mice , voles and shrews were found in food analyzes . Dormice , moles , squirrels , weasels and bats were found less frequently . Great tits , treecreepers , flycatchers , bunting , smackers and the wren dominated the birds . Very rarely found insects, frogs and toads , salamanders and other snakes such as the grass snake or smooth snake . The spectrum is of course very much dependent on the regional composition of the potential prey. As young animals, they mainly prey on small lizards and nest-young mice.

The foraging takes place mainly on the ground and in caves in the ground, also under stones, in trees or in plant material. Larger prey are strangled, while smaller animals such as lizards are crushed between the jaws. The snake often lives in attics, haystacks and the like, which it keeps free of mice.

The Aesculapian snake itself is prey to various birds and mammals. Among the mammals, it is primarily martens such as the polecat , the badger as well as stone and pine marten ; among birds there are the buzzard , the honey buzzard , the short-toed eagle and various corvids . Young animals in particular are also preyed on by other species of snake such as the stair snake or the lizard snake . When threatened, the Aesculapian snake flees to higher areas or to trees and bushes. When threatened, she defends herself with defensive bites and drains a foul smelling secretion from her anal glands .

Reproduction and development

The mating season of the snakes is in the phase after the hibernation in May. Aesculapian snakes play a mating game in which the male tries to grab the female by the neck and hold on to it (neck bite). Only when this has happened does the actual mating take place. If several males are together, it comes to comment fights in which the two opponents wrestle with each other until one is pressed to the ground. There are no injuries.

The eggs are laid in July in moist soil, in plant remains, under stones or in crevices as well as in old tree stumps. The female lays a clutch of five to ten oval eggs, from which the young hatch in September.

Taxonomy

The first valid scientific description of the Aesculapian snake comes from Josephus Nicolaus Laurenti in 1768; however, the snake was already well known beforehand. For example, Ulisse Aldrovandi described it as Anguis Aesculapii in his Historia animalium in 1640 and Carl von Linné is said to have described it as Coluber aesculapii in 1766 (some systematics still use this reference today and currently name the species Erythrolamprus aesculapii L., 1766). Laurenti named the snake Natrix longissima and placed it next to the grass snake ( Natrix natrix ); later they were mostly called Coluber longissima and classified accordingly under the wrath snakes . In 1833, Leopold Fitzinger coined the Elaphe genus for the climbing snakes, into which the Aesculapian snake was only introduced in 1925 by Robert Mertens . This classification was valid until the last revision a few years ago; since then it has had the generic name Zamenis , which was also used occasionally in the 19th century. In addition to the Aesculapian snake and the Italian Aesculapian snake, only the leopard snake ( Zamenis situla ) was also placed in this genus among the snakes living in Europe .

Some herpetologists continue to use the name Elaphe longissima for the Aesculapian snake . In addition, four genetic lines to be interpreted phylogeographically are distinguished internally : Western haplotype , Adriatic haplotype, Danube haplotype and Eastern haplotype.

The Aesculapian snake as a symbol

The snake was named after the Greek Asclepius ( Latin Aesculapius ), around whose staff such a snake was wrapped.

There is also the theory that this is actually the medina worm , which is traditionally removed from a patient's subcutaneous tissue by slowly winding it on a stick. However, this theory is rejected by critics, since the Medina worm was only known in Africa, which means that an occurrence of this worm in Greek mythology is unlikely.

The staff of Aesculapius is still used today as a symbol for medical professionals . If the Aesculapian stick is between the “legs” of the capital letter “V”, it is a symbol of veterinarians . For pharmacists and pharmacists , the Aesculapian snake winds around the shaft of a drinking bowl. It is the bowl of Hygieia , a daughter of Asclepius. This small symbol is clearly visible on the large Fraktur "A" in German pharmacies.

The World Health Organization of the United Nations, WHO, uses the snake as a symbol in its official flag and the Aesculapian staff is also used in the Star of Life , the international symbol for emergency medical services . It is also the specialist service badge for the medical service . The snake, once turned over, and the stick - with a very small bowl - form an "A" as the logo of the Austrian Chamber of Pharmacists, which can also be seen at almost all pharmacies, only a few still have the previous logo with Fraktur-A Austrian Chamber of Pharmacists. The coat of arms of the village of Schlangenbad shows the adder with a crown.

In Italy the Martians tribe were known as snake worshipers and snake tamers. Already 3000 years ago they worshiped Angitia , the goddess of snakes and poisons. Even today , a snake procession (festa dei serpari) in honor of San Domeniko Abbate takes place in the small town of Cocullo in Abruzzo every first Thursday in May . Aesculapian snakes and four- lined snakes ( Elaphe quatuorlineata ) are carried through the streets. Numerous living snakes surround the wooden figure of the saint.

Hazard and protection

The Aesculapian snake has a relatively large range and is not threatened as a species. In the individual parts of their distribution area, however, the situation is different: especially at the northern distribution limit, which also includes the few populations in Germany, their occurrence is very isolated, and there is no connection between the individual populations. This disjunction is attributed to the climatic changes of the last centuries, in which the animals have increasingly withdrawn to warmer regions. Habitat changes by humans intensify this tendency, which could lead to the extinction of individual populations. Accordingly, the Aesculapian snake is classified in category 2 - highly endangered - in the Red List of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Although the habitat destruction in the habitats of the Aesculapian snake is only seen as a secondary cause of retreat, there are a number of recommendations to keep this factor as low as possible. The intensification of forestry and agriculture as well as land consolidation and settlement expansions represent the most massive human encroachment on the animal habitat. In order to protect the populations, primarily core distribution areas are designated as protected areas, such as the extensively used meadows and orchards in the Neckar-Odenwald. At the same time, forest edge areas as wintering zones as well as potential egg-laying places in dead wood and old trees have to be included in the protection. It is possible to support the deposits by means of artificially created piles of wood chips or to maintain them until natural oviposition possibilities are available again.

Legal protection status (selection)

- Habitats Directive : Annex IV (species to be strictly protected)

- Federal Nature Conservation Act (BNatSchG): strictly protected

Red list classifications (selection)

- Red List of the Federal Republic of Germany: 2 - endangered

- Red list of Austria: NT (threat of danger)

- Red list of Switzerland: EN (corresponds to: highly endangered)

literature

- Edwin N. Arnold & John A. Burton: Parey's Reptile and Amphibian Guide to Europe . Paul Parey Publishing House, Hamburg and Berlin, 1983. ISBN 3-490-00718-2

- Axel Gomille: The Äskulapnatter Elaphe longissima - Distribution and way of life in Central Europe . Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt, 2002. ISBN 3-930612-29-1

- Ulrich Gruber: The snakes in Europe and around the Mediterranean . Franck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1989. ISBN 3-440-05753-4

- Michael Gruschwitz, Wolfgang Völkl, Paul M. Kornacker, Michael Waitzmann, Richard Podloucky, Klemens Fritz & Rainer Günther: The snakes in Germany - distribution and stock situation in the individual federal states . Mertensiella 3, 1993: pages 7-38. ISBN 3-9801929-2-X

- Rainer Günther (Ed.): The amphibians and reptiles of Germany . Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena, 1996. ISBN 3-437-35016-1

- Ulrich Joger, Daniela Guicking, Svetlana Kalyabina-Hauf, Peter Lenk, Zoltan T. Nagy & Michael Wink: Phylogeography, speciation and post-Pleistocene immigration of Central European reptiles. - In: Martin Schlüpmann & Hans-Konrad Nettmann (eds.): Areas and distribution patterns: Genesis and analysis. - Zeitschrift für Feldherpetologie, Supplement 10: 29–59, Laurenti-Verlag, Bielefeld, 2006. ISBN 3-933066-29-8

- Axel Kwet: Reptiles and Amphibians of Europe . Franck'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 2005. ISBN 3-440-10237-8

Web links

- naturschutzhaus-wiesbaden.de

- The Äskulapnatter in Austria on www.herpetofauna.at: Species description, distribution and pictures

- Biology and funding opportunities through the creation of piles of wood chips

- Photos of the Aesculapian snake on www.herp.it

- Zamenis longissimus in The Reptile Database

- Zamenis longissimus inthe IUCN 2013 Red List of Threatened Species . Posted by: Aram Agasyan, Aziz Avci, Boris Tuniyev, Jelka Crnobrnja Isailovic, Petros Lymberakis, Claes Andrén, Dan Cogalniceanu, John Wilkinson, Natalia Ananjeva, Nazan Üzüm, Nikolai Orlov, Richard Podloucky, Sako Tuniyev, Uğur Kaya, Rast, Wolfgang B Ajtic, Milan Vogrin, Claudia Corti, Valentin Pérez Mellado, Paulo Sá-Sousa, Marc Cheylan, Juan Pleguezuelos, Bartosz Borczyk, Benedikt Schmidt, Andreas Meyer, 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- Photos of the Aesculapian snake on www.blenderwahl.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ Otto Aßmann: Aesculapian snake project - request for reports to the Aesculapian working group . In: The Bavarian Forest. Journal for natural science education and research in the Bavarian Forest , Volume 29 (new series) Issue 1 + 2 / December 2016, pp. 91–94

- ^ Aesculapian snakes - weird roommates in the Odenwald. August 17, 2019, accessed August 23, 2018 .

- ↑ Patrick Leigh Fermor: The snakes of St. Dominic. In: welt.de . June 30, 2006, accessed October 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Klaus-Detlef Kühnel, Arno Geiger, Hubert Laufer, Richard Podloucky & Martin Schlüpmann: Red list and list of total species of reptiles in Germany. P. 231–256 in: Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (Hrsg.): Red list of endangered animals, plants and fungi in Germany 1: Vertebrates. Landwirtschaftsverlag, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3784350332

- ↑ Assmann, O. (2013): Artenschutzpraxis: Creation of piles of wood chips as egg-laying places for Aesculapian snake and grass snake. - ANLiegen Natur 35 (2): 16–21, running. PDF 0.5 MB