Mohori (wind instrument)

Mohori , also mohorī, mahurī, muhuri, refers to several double-reed instruments played in Indian folk music in the central and eastern Indian states of Odisha , Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal . Since the turn of the century, reed instruments consisting of two game reeds can be detected in India , which with a few exceptions disappeared in the following centuries. The name mohori goes back to the oldest Indian names for double reed instruments , Sanskrit mavari and madvari , which are mentioned for the first time between the 6th to 9th centuries and provide evidence that this type of wind instrument has a pre-Islamic origin in India. In the Islamic Middle Ages , double-reed instruments (cone oboes) and ways of playing were added under Arabic-Persian names. The entire group of wind instruments is collectively called mukhavina in India .

Origin and Etymology

In the eastern Mediterranean and Mesopotamia , double wind instruments, which consist of two reed instruments blown at the same time, are much older than in India. In the tombs of Ur in Mesopotamia, a silver double wind instrument from the 3rd millennium BC remained. Received. Since the Egyptian 18th dynasty (16th to 14th centuries BC), double wind instruments, corresponding to the aulos of ancient Greece, have appeared frequently . Relief images of musicians with double wind instruments from southern Central Asia and in Buddhist art from Gandhara have come down to us from the time of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (2nd / 1st century BC) . Similar images can be found in India at Stupa I of Sanchi (1st century BC) and in the kushana temporal Mathura (2nd century AD). Consequently, the reed instruments seem to have come to India from the northwest around this time, following the conquests of Alexander the Great . They are not recognizable in evidence of the prehistoric Indus culture or in pre-Christian ancient Indian literature. The ritual and military tasks of the medieval wind instruments (cone oboes, trumpets) were taken over by snail horns ( sankha ) in ancient India , for example from the description of the great battle in the Bhagavad Gita (originated in the second half of the 1st millennium BC .). The wind instruments depicted in Sanchi appear to have been conical, but did not have a bell. On the later relief by Mathura two parallel conical tubes with bell can be seen. After the middle of the 1st millennium, references to conical double wind instruments in India disappeared almost completely. Today there are only a few regions with double single-reed instruments of a different type with cylindrical play tubes, which correspond to the oriental zummara . This includes in India as an instrument of snake known Pungi , the rare tarpu who only occasionally in folk music in the western Indian state of Maharashtra occurs and with Mohori spoke related mahuvar in Gujarat .

In place of the illustrations of double wind instruments in antiquity, which can at least be assumed to have had reeds, there are written sources from the 9th century that clearly mention double reed instruments. Probably the oldest text in which the Sanskrit name mavari , also madvari , occurs is the treatise Brihaddeshi by the music scholar Matanga , written between the 6th and 8th centuries - i.e. before the Muslim conquests . These include the Sanskrit names madhukari and madhukali , which correspond to mahudi and magudi in the South Indian languages : regional names for the pungi in South India, with which the word mohori for the North Indian cone oboe is related. The instrument name mavari ( madvari ) also occurs in the writings of the music scholar Nanyadeva (11th century), in the musicological work Sangita-Ratnakara of Sarngadeva (13th century), in the Sangit Chintamani of Vema (Vemabhupal, 14th century) and in the Abhinava Bharata Sarasangraha by Mummadi Chikkabhupala, a 17th century author. Poets who write in Kannada and call the wind instrument mouri include Raghavanka (13th century) in his work Harishchandra Kavya , Singiraja in Singiraja Puranam (around 1500) and Govindavaidya around 1650 in Kanthirava Narasaraja Vijaya . The composer Purandara Dasa (1484–1564), who is revered as one of the founders of South Indian music, mentions the word mouriya in some of the lyrics (Kannada suladi , corresponding to Sanskrit gita ) .

The origin of the word context of mohori is unclear. According to a suggested derivation from Sanskrit, mavari is a corrupt form of madhukari and this is composed of madhu , “sweet” and kari , “something that sounds”, which refers to a melodious wind instrument. Alternatively, BC derives Deva mohori from mori , which means “tube”, “gutter” in Kannada, Hindi and Marathi and refers to the shape of the instrument. There is a comparable linguistic reference to the form between Sanskrit sushira , "hollow", and the Indian classification of wind instruments as sushira vadya ("hollow instrument"). The Khasi , an indigenous people in Meghalaya in north-east India, play the tangmuri , which may be related to their name , where muri means "drain" in Khasi . Alastair Dick traces mahvari back to the Arabic word mizmar and considers madhukari to be a wrong re-Sanscritization of it.

Apart from the trace that goes back to ancient Indian times, Indian double reed instruments are linked to the Arab-Persian tradition in terms of design and playing style. At the beginning of the 8th century, the first Muslim conquerors reached the northwest Indian region of Sindh . Muslims brought with them the Arabic reed instrument mizmar , which was part of the military orchestra. From the 10th century the Arab-Persian palace orchestra naubat can be traced in Arab countries; In the Mughal period it was an essential part of courtly ceremonies. This orchestra consisted of various trumpets ( karna and nafīr ), cone oboes ( surna , forerunners of today's shehnai ) and large drums ( naqqara , nagara ). According to a description from the 16th century, the ceremonial orchestra consisted of 60 to 70 musicians. It occurred on certain occasions, such as the arrival of high dignitaries, and at fixed times of the day in front of palaces and mausoleums. The secular tradition around the rulers' courts in India also passed into the religious area. For example, at the entrance of some North Indian Hindu temples ensembles with shehnai, sur shehnai (a drone - shehnai ), dholak (barrel drum) and nagara ( kettle drum played in pairs ) make music .

The widespread combination of shehnai and kettle drum goes back to an oriental musical tradition and corresponds, for example, to the interplay of zurna and davul in Ottoman military bands. This connection is confirmed for the tradition also maintained in India by a list of related expressions for cone oboes, which proceed from the Persian surnai to the west via the Turkish zurna to the Macedonian zurla and to the east via India to the Burmese hne , Cambodian sralai , the sarune occur among the Batak , the sruni on Java and up to the Chinese suona . With the word surnai , the names of other Arabic-Persian instruments used by military bands also spread. The Persian beaker drum tombak became tumbaki in India , while the Persian short natural trumpet was called buq in Georgia, buki, and in India, bukka . Obviously, the word surnai found its way into different languages and cultures, but this does not necessarily mean that a certain type of musical instrument should be adopted, nor does it contradict the fact that the Indian bowling oboe already existed in pre-Islamic times. Nazir A. Jairazbhoy revised the thesis put forward in 1970 that the cone oboes shehnai, nadaswaram and mohori have no Indian precursors and come from the medieval Near and Middle East.

The linguistic environment of mohori includes the double reed instruments common in central India and northeast India, mahuri in Odisha and West Bengal, mohuri in Madhya Pradesh , mohori in Odisha and Assam , tangmuri with the Khasi in Meghalaya, mauri dizau in Nagaland , mvahli or muhali in Nepal and mori in Karnataka .

Design and style of play

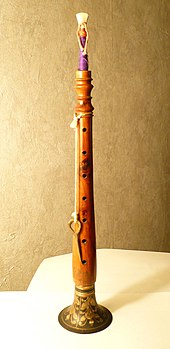

Mavari

With the word mavari ( mahvari ), madvari or madhukali a reed instrument occurs in medieval Sanskrit texts, first in Matanga's treatise Brihaddeshi . In Manasollasa , a general lexicon written by King Someshvara in the 12th century, an approximately 53 centimeter long wind instrument muhuri with a very likely conical playing tube is described. The same information is also found in the Sangita Ratnakara of the 13th century for the wind instrument called madhukari there . This was either entirely made of wood or had a bell made of horn. The bottom diameter of the opening was 3.75 centimeters. The shape was similar to the straight metal trumpet kahala , which was important in the Middle Ages . The game tube had seven finger holes on top and one thumb hole between the top and the first finger hole on the bottom. The mouthpiece consisted of a three-inch long copper tube with a lip support made from a clam shell or ivory. At the end, a reed made of reed was tied, which should have provided a pleasant sound.

Odisha

The mohori , also mahuri or sonai, played in Odisha is slightly larger than the north Indian shehnai and smaller than the nadaswaram played in south India . Nazir A. Jairazbhoy (1970) found two different variants in the coastal region of Odisha in the 1960s, which indicate that the mohori belongs to two musical traditions that meet here: to the folk music ensembles ( baja ) of Odisha and that in the Telugu-speaking state of Andhra Pradesh beginning South Indian folk music tradition ( Telingi baja ). The South Indian mohori is similar to the nadaswaram and, like this, has a detachable bell. The bell and mouthpiece are made of brass. The village ensemble is made up of low-caliber, professional musicians who, in addition to mohori, play the barrel drums ghasa (corresponding to the South Indian tavil ) and dhol .

The mohori , which belongs to the North Indian shehnai tradition, is smaller and consists of an externally conical wooden tube with an almost cylindrical bore and a brass bell. In such an ensemble, for example, two mohori with two frame drums cangu and two kettle drums nagara play together.

Musicians of the Pana caste near Puri tell an original legend of the mohori . During a period of drought when the Mahanadi had very little water, Mukunda Deva, the last ruler of a Hindu kingdom in eastern India, went to the site of the present-day city of Prayagraj (Allahabad) at the confluence of the Ganges , Yamuna and the mythical underground Sarasvati River to achieve through a twenty-one day meditation that water drains into the Mahanadi. Before that, he threatened to divide everything or everyone into three parts, whatever or whoever should disturb him in his meditation. Just as the king was meditating, in 1568, Muslim troops under Akbar advanced to Oriya and announced their arrival with a loud sound of the long trumpet kahali . Mukunda Deva kept his oath and cut the trumpet into three parts. This explains why the mohori consists of three parts, and Jairazbhoy (1970) concluded, among other things, from the link between the Muslim conquest and the form of the mohori, from the link suggested in the legend .

The dance drama Chhau , performed in rural regions in East India, is usually accompanied by an ensemble with the large kettle drum dhamsa , the barrel drum dhol and the shehnai or mohori as the only melodic instruments. According to a description of Mayurbhanj Chhau , a variant of Chhau that is performed in the northeast of Odisha, the accompanying orchestra consists of the drums dhol, chadchadi (small cylinder drum), nagada (kettle drum) and dhamsa as well as the melody instruments mahuri, tuila (single-stringed zither) and occasionally a bansi (bamboo flute).

In the temples in Odisha which, according to the Shaktism tradition, serve to worship female deities - Sarala ( Sarasvati ), Karnika Devi or Mangala Devi, dances are performed during religious ceremonies and songs are sung in honor of Shiva . A major religious dance festival for the vast majority of Hindu believers in southern Odisha is danda nata (also danda jatra ). The accompanying ensembles play mahuri, khol (two-headed clay drums) and gini ( cymbals ).

Mohori made from bamboo in central India

A version of the mohori in rural areas of Odisha with a play tube made of bamboo and a bell made of brass or bronze represents either a parallel development to the wooden mohori or a "fallen" (more simply copied) version of it. It consists of three cylindrical bamboo tubes with different diameters, which are pushed into one another so that the gradation results in an approximately conical bore. This mohori is used to accompany folk dances and at village festivals.

Occasionally the play tube is made from two differently sized bamboo tubes which, when plugged into each other, result in a stepped hole. A form of mohuri in Madhya Pradesh and Odisha, which is also called sonai , has a one-piece, cylindrical bamboo tube with seven finger holes and a brass bell attached. The musicians often belong to the cathedral, a caste of craftsmen, farmers and drummers or other low castes. They make the bamboo play tubes themselves and buy the brass bells from craftsmen who sell them at markets in small towns.

In an ensemble called dulduli ( baja ) in the west of Odisha, the simple but powerful and fast played rhythms with the barrel drums dhol and mandal , the kettle drum tasa (also nissan ), the frame drum tamki and the pair cymbals jhanj (also kastal , alternatively the rattle jumka ), the mohuri (or muhuri ) is the only melody instrument and is considered the leader (" guru ") of the ensemble. The muhuri used for this is made up of a five centimeter long blowing tube, an approximately 18 centimeter long bamboo play tube and an approximately ten centimeter long brass or bronze bell.

The dulduli ensemble that appears on traditional occasions in villages is also called ganda baja , because there it consists exclusively of members of the lower caste Ganda (also Pano). Another name of the ensemble, panchabadya , refers to the five ( panch ) different musical instruments that ideally make it up. The large barrel drum dhol sets the rhythm, while the mahuri has the task of imitating either the moody voice of a seductive woman or the desperate call of a woman for her deceased child. The shrill tones of the mohuri should sound accordingly expressive .

Before the Ganda musicians begin their game, they hold a consecration ceremony for their musical instruments. The use of the instruments can in turn serve the worship ( puja ) of the gods. The drums are considered suitable for inducing a trance during temple rituals .

Other regions

In Nepal , most musical instruments are assigned to certain castes and are only played by them. The Damai are a caste of tailors and musicians at the lowest social level. They play on behalf of various ethnic groups for entertainment at weddings with various drums, the bowling oboe shehnai and curved trumpets ( narsimga ). On religious occasions, a Damai plays the kettle drum nagara together with a member of the Kusle caste who blows muhali on the bowling oboe . The Kusle only perform for Newar .

In Assam , in addition to the wooden tangmuri of the Khasi, there is a mohori with a play tube made of bamboo and six finger holes instead of the seven common in central India.

literature

- Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva: The Double-Reed Aerophone in India. In: Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council. Volume 7. 1975, pp. 77-84.

- Alastair Dick: The Earlier History of the Shawm in India. In: The Galpin Society Journal. Volume 37, March 1984, pp. 80-98.

- Alastair Dick: Mahurī and Mahvarī. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Volume 3. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 368.

- Alastair Dick: Mohorī. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments. Volume 3. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2014, p. 494.

- Nazir A. Jairazbhoy: A Preliminary Survey of the Oboe in India. In: Ethnomusicology. Volume 14. No. 3, September 1970, pp. 375-388.

- Nazir A. Jairazbhoy: The South Asian Double-Reed Aerophone Reconsidered. In: Ethnomusicology. Volume 24. No. 1, January 1980, pp. 147-156.

Web links

- Amulya Kumar Pati: Lost in oblivion, mohuri tune. telegraphindia.com, October 15, 2010.

- Video by AjitGadtya Kumar: Folk music.Orissa. Jhaptupali on YouTube, July 17, 2011 (2:17 minutes; Mohori solo in Jhaptupali village, Patnagarh sub-district ).

- Video by Amrita Sabat: Dhol Mahuri: Awesome beats from Bhadrak, Odisha on YouTube, March 2, 2015 (1:42 minutes; drum-dance ensemble in the city of Bhadrak near the coast of Odisha).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann : Old India. Music history in pictures. Volume II. Ancient Music. Delivery 8. Ed. Werner Bachmann. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1981, p. 62.

- ↑ Alastair Dick, 1984, pp. 82-84.

- ↑ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva, 1975, pp. 78f.

- ↑ a b c Alastair Dick: Mahvarī. In: Laurence Libin (Ed.): The Grove Dictionary of Musical Instruments, 2014, p. 368.

- ↑ Nazir A. Jairazbhoy, 1970, p 377th

- ^ Dileep Karanth: The Indian Oboe Reexamined. The debate regarding the appearance of the oboe in India. ( Memento of February 18, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) In: Asian Studies on the Pacific Coast.

- ↑ Nazir A. Jairazbhoy, 1970, p 383f.

- ↑ Kapila Vatsyayan: Mayurabhanj Chhau. In: Eknath Ranade (ed.): Vivekananda Kendra Patrika. Distinctive Cultural Magazine of India. Vol. 10, No. 2 ( Theme: Dances of India ) August 1981, pp. 93–117, here p. 96.

- ↑ Ashok D. Ranade: Orissa. In: Alison Arnold (Ed.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 5: South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent . Routledge, London 1999, p. 733.

- ↑ Alastair Dick: Mohorī. 2014, p. 494.

- ↑ Nazir A. Jairazbhoy, 1970, p 384th

- ↑ Dulduli baaja - Kosali / Sambalpuri Folk Music of Kosal region . Youtube video

- ↑ Muhuri. In: Late Pandit Nikhil Ghosh (Ed.): The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Music of India. Saṅgīt Mahābhāratī. Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2011, p. 691.

- ↑ Lidia Guzy: Dulduli: the music 'which touches your heart' and the re-enactment of culture . (PDF) In: Georg Berkemer, Hermann Kulke (Eds.): Centers out There? Facets of Subregional Identities in Orissa. Manohar, Delhi 2011, p. 3f.

- ^ Felix Hoerburger: Studies on Music in Nepal . (= Regensburg contributions to musical folklore and ethnology. Volume 2). Gustav Bosse, Regensburg 1975, p. 43.

- ↑ Bigamudre Chaitanya Deva, 1975, p. 89.