Khasi

The Khasi - proper name Ki Khasi (" those born of a woman") or Ki Khun U Hynniewtrep ("the children of the seven huts ") - are an indigenous people in northeast India with over 1.4 million members in the small state of Meghalaya in the forerunners of the Himalaya mountains; they make up about half of the total population there. Around 35,000 Khasi live in the neighboring state of Assam and around 100,000 in Bangladesh, bordering to the south . The Khasi form a matrilineal society based on maternal lines in which descent, family name and succession are only derived from the mother, not the father. These relationships are anchored in the constitution of Meghalaya, also for the matrilineal neighboring people of the Garo ; Both founded the state in 1972, the Indian constitution guarantees them special protection and self-government rights as “registered tribes” ( Scheduled Tribes ). According to the Khasi tradition, land ownership is only in the hands of women; it ensures social and economic independence and security for the mothers and their extended families . Men belong to their mother's extended family , inherit the family name and clan affiliation from her and contribute to their upkeep; they are part of the community of solidarity, but usually cannot inherit any land. After a marriage, the husband usually moves in with his wife and her mother ( matrilocal order of residence ), and his children will belong to their extended family. The wife's brother is considered her protector and advisor and will traditionally look after her children as a social father ( avunculate of the mother brother ).

Most families practice traditional plant cultivation with animal husbandry as an on- demand economy and trade in excess crops on the weekly markets of around 3,000 Khasi village communities ; Men are almost always appointed as village chiefs . Families that belong together form associations ( clans ) which, in addition to their clan mothers, also have elected leaders ( chiefs ). The 3363 clans of the Khasi tribes, some of them very large, organize themselves politically as a tribal society , divided into 64 clan chiefdoms . The original origin of the Khasi is believed to be in the east, in the area of the Mekong River ( see below ), because the Khasi language is in no way similar to the neighboring Indian languages. 83% of the Khasi are Christians from different churches, but also maintain their traditional, animistic religion Niam Khasi with ancestor worship and holy forests as well as their own egg oracle . Some Khasi villages became world famous for their large root bridges made from living rubber trees (see pictures ).

| Khasi |

|---|

|

Recordings from Moulvibazar (Khasi Mountains, Sylhet District , Bangladesh, 2012)

|

| population |

|

Khasi in Meghalaya ( 2011 )

1,412,000 of 2,967,000 inhabitants. = 48% ≈ 260,000 Khasi households (from 1 person) ≈ 78 % live in rural areas , 22% in urban areas ≈ 74% reading ability in Meghalaya ≈ 44% employment ; 4.8% unemployed ≈ 55 % of the tribal people of Meghalayas ≈ 83 % Christians (different churches) Indigenous religion: Niam Khasi (15%) Historical |

| Meghalaya |

Meghalayas 11 administrative districts Khasi settle in the center and east in six districts of The whole Khasi area outlined in red, |

language

The Khasi is not an Indo-European language like most in India, but a Mon- Khmer language , closely related to Cambodian and Vietnamese . It is assumed that they are related to some isolated languages in central India: the Khasi could have a bridge function between these and the large Austro-Asian language family , which originally came from China.

Khasi is divided into numerous dialects and has been an associated official language in Meghalaya since 2005 (alongside Garo and English); the four main dialects are Khasi, Pnar / Synteng (Jaintia), War and Lyngngam (names of Khasi sub-tribes). The 2011 census in India indicates 1,431,300 speakers, including the 1,411,800 Khasi in Meghalaya, 16,000 in the state of Assam and 1,000 Khasi in neighboring Mizoram . Broken down according to dialects, the result is: 1,038,000 speak Khasi, 319,300 speak Pnar / Synteng (Jaintia), 51,600 speak War, 11,600 speak Lyngngam and 10,900 other dialects.

The Khasi do not have their own script; from 1840 British Methodist missionaries introduced the Latin alphabet , and from 1890 the first Khasi-English dictionary and a translated edition of the Christian Bible appeared . In 1896 the first Khasi printing house was founded under the name Ri Khasi Press ("Khasiland-Verlag").

Today the Khasi in written and spoken form is a living language with its own literary tradition. In Meghalaya several newspapers appear in Khasi and there are radio programs and two television stations that broadcast exclusively in Khasi (see below on current conflict issues in the Khasi ). In 1984 the first color film appeared on Khasi: Manik Raitong by Ardhendu Bhattacharya , based on a folk legend of the Khasi; he was awarded the Indian National Film Award . In 2016 a translation of the Bible into the Khasi colloquial language appeared.

In 2000, the Meghalayas Ministry of Culture led a symposium on the life and works of Khasi authors ("Life and Works of Khasi Authors in the field of Khasi Literature") and a year later a conference on the promotion of Khasi and the neighboring Garo ("Growth and Development of Khasi and Garo Languages ") . In addition, the Ministry awarded the first literary prize State Literary Award 2000 for Khasi book .

The Khasi folklore knows a unique form of individual poetry , called phawar , which is used particularly in archery: With imaginative lectures in rhyming two-line lines, one's own advantages are praised and the weaknesses of opponents are mocked ( see below ).

education

In 1924, the first secondary school ( college ) was founded by the Irish Christian Brothers in what is now Meghalaya . The reading ability ( literacy ) increased from a low 27% in 1961 to 63% in 2001 and further to 74.4% in the 2011 census and was thus just above the India-wide average (73%). 77% of the Khasi were able to read and write, while the rate of women was 79%, 3% higher than that of men (see below for the gender-specific data ). Meghalaya has more than 14,000 schools, over 500 colleges and 10 universities , the majority of which are private. The largest is the state-owned North Eastern Hill University, founded in 1973 in the capital Shillong. The university has two linguistic departments, the Khasi Department and Garo Department, and the anthropological Anthropology Department , while the Meghalayas Ministry of Culture operates the Tribal Research Institute for the study of tribes ( Scheduled Tribes ). Here, Khasi professors and PhD students also research their own traditions and their changes, especially with regard to their matrilineal gender order .

In Shillong, the Christian Salesians have been running the “Don Bosco Center for Indigenous Cultures ” (DBCIC: Don Bosco Center for Indigenous Cultures ) with the large anthropological Don Bosco Museum since 2001 . The DBCIC includes research, publications, training and animation programs related to the cultures of Northeast India and the surrounding area.

Settlements

The area of the Indian state of Meghalaya includes the Shillong Plateau, an elevation that lies in front of the great Himalayan mountains and rises from 30 meters above sea level to 1500 meters. In the middle, the mountainous chains of hills enclose a plateau on which a small elevation rises to almost 2000 m . Meghalaya roughly corresponds to a rectangle with about 300 km from west to east and about 100 km from south to north. The great Brahmaputra river flows around the state in the north and west, the horizontal southern edge of the plateau drops steeply to low-lying Bangladesh . The middle third of the state's area is formed by the Khasi Mountains (Khasi Hills) , whose name is derived from the people who were first mentioned as resident here around 1500 AD under the name "Khasi" (see below for origin ). The hilly mountains with the extensive plateau are divided into three administrative districts : West Khasi Hills , South West Khasi Hills (from 2012) and East Khasi Hills . The majority of the Khasi live in the area of the plateau on which the capital Shillong is located (about 150,000 inhabitants); Shillong Peak rises to 1966 m , the highest point in Meghalaya. The whole plateau is fragmented, traversed by deeply cut gorges and valleys with great differences in altitude of 600 to 1900 meters.

Cloud country

The newly formed Sanskrit name Meghalaya means " Abode of the Clouds" and thus describes one of the rainiest areas in the world with over 120 rainy days in the extensive rainy season between April and October. In the south of Meghalaya, the Khasi mountains drop steeply and cause the rising monsoon clouds to rain down. Here, the mountain town of Cherrapunji has held the world record for the highest annual amount of precipitation (26.5 meters ) since 1861 , the village of Mawsynram has held the world record for the highest average annual amount (11.9 meters) since 2015. A part of this persistent monsoon rain flows off in countless waterfalls , the Nohkalikai Falls are the highest in India with 340 meters.

Ecoregion

The vegetation of the Khasi area consists mainly of monsoon forests , divided into three climatic zones: At altitudes between 30 and 300 meters there are tropical lowland rainforests and between 300 and 1100 meters subtropical wet forests , which extend up to the moderate altitude between 1100 and 1900 meters extend, with patchy cloud and cloud forests . Bamboo forests cover 14% of Meghalaya's area; a total of 12% of all wooded areas are state-owned and are looked after by supervisors.

Meghalaya is part of the Asian biodiversity hotspot Indo-Myanmar (Hotspot 19). The WWF ecoregion Meghalaya Subtropical Forests (IM0126) covers the entire elevation with its mountains and the high plateau and is considered to be one of the most biodiverse in Asia, with an exceptionally large number of indigenous plant and animal species. Hundreds of orchids , many original rice, banana and citrus species (such as the Khasi mandarine ), some magnolias ( Michelia ) and India's only pitcher plant: Nepenthes khasiana ("khasiana / khasianum" denotes endemic species of the Khasi mountains) come from here. . In Meghalaya 139 mammal species, including the living Asian elephant , the Bengal tiger , the clouded leopard , the endangered gold and leopard cats and seven primates such as the White-browed gibbon ( "little ape") and some macaques . 659 bird, 107 reptile and 152 fish species were identified. The WWF (World Wide Fund For Nature) states that two thirds of the entire ecoregion has already been deforested or degraded and the 7 state-protected areas make up less than 1% of the ecoregion. Large-scale mining of coal, limestone and uranium and the corresponding infrastructures also contribute to deforestation. The state Wildlife Institute of India (wii) states in 2017 that a total of 6% of the state area of Meghalaya is protected as various types of protected area. The more than 100 sacred forests of the Khasi make only a small contribution to the urgently needed reforestation ( see below ).

Khasi groups

The varied nature between sea heights of 30 m at the edge of the area to over 1900 meters in the southern center is one of the reasons why clear differences have developed between the many Khasi villages and groups in terms of economy and way of life, dialects and traditions, despite their common language and social organization.

The Khasi are surrounded by several small tribes who count themselves among the Khasi and speak one of the main Khasi dialects or a related Mon Khmer language ; they are grouped together in censuses: "Khasi, Jaintia, Synteng, Pnar, War, Bhoi, Lyngngam" (see also the " Seven Huts " below ):

- the Jaintia (also: Synteng / Pnar) settle in the east in the Jaintia Mountains, since 2012 divided into the districts of West Jaintia Hills and East Jaintia Hills

- the Bhoi settle in the northeast on the border with Assam , in the district of Ri-Bhoi

- the War settle in the south on the border with Bangladesh (differentiated into War-Khasi and War-Jaintia)

- the Lyngngam settle in the west on the Garo Mountains (Garo Hills)

The 2011 Indian census identified 1,431,300 speakers of the Khasi: 1,038,000 speak Khasi, 319,300 speak Pnar / Synteng (Jaintia), 51,600 speak War, 11,600 speak Lyngngam and 10,900 other dialects.

The Christian missionary Joshua Project lists the Khasi in early 2019 with 1,470,000 members in Meghalaya; for the subgroups are given: 333,000 Bhoi, 77,000 War, 34,000 Lyngngam and 17,000 Khynriam. For the neighboring state of Assam 42,000 Khasi are recorded, in neighboring Mizoram 1000, in Nagaland 1,100, in West Bengal 1,400 as well as smaller groups in other states. A total of 1,518,000 Khasi are given for India, 83.5% of which are Christian. For Bangladesh, which borders on Meghalaya to the south, 85,000 Khasi are given, 84.3% Christian, about 48,000 in the border region to Meghalaya in the Sylhet district and 30,000 in the capital Dhaka .

The Khasi have close ties to the neighboring large matrilineal Garo people with almost 900,000 members throughout the western part of Meghalaya - together they established their own state in 1972 ( see below ). 15 other tribal populations are represented in Meghalaya (2011): Hajong (39,000 members), Raba (33,000), Koch (23,000), Karbi (19,000) and other smaller ones such as the Synteng (1,600; an independent group in the east and in Assam). The 17 tribal peoples together made up 86.1% of the total population in 2011, the Khasi alone 47.6% and the Garo 27.7% (compare demography of Meghalaya ). In 2001 the Khasi and Jaintia were 13th of the largest tribal peoples in India with 1.1 million members , the Garo 22nd with 0.7 million.

Village communities

The 2011 Indian census counted 6,450 villages in Meghalaya (380 uninhabited). 20% of the total population live in the 22 cities, a quarter of them at 1,500 m in the capital Shillong (143,000). Many Khasi also live here, because parts of the large city district belong to their ancestral area; in comparison, only 78% of the Khasi live in rural areas. The 1,411,800 Khasi make up around 48% of the population (2,966,900) and 55% of the state-protected tribal population ( Scheduled Tribes : 2,555,900). Since 2001 the number of Khasi has grown by 26% and the population by 28%.

In 2001 5780 villages were counted, 80% of the 2.3 million inhabitants lived in rural areas, as in 1991 when there were 5500 villages and 1.8 million inhabitants in Meghalaya. The proportion of the recognized tribal population was already over 90% when the state was founded in 1972.

Since 1981 with around 4900 villages and 1.3 million inhabitants, the population of Meghalaya has more than doubled to around 3 million in 2011, a population explosion of +122%, combined with extensive conflicts ( see below ). Nevertheless, Meghalaya, with a population density of only 132 per square kilometer, is one of the most sparsely populated states in India, like other of the " Seven Sister States " in northeast India (compare the basic data for the states / territories ). In 2001 this density was 102 inhabitants per km².

Since there are only a few flat areas in the whole of Meghalaya and hardly any wide river valleys, most of the approximately 3000 villages of the Khasi are located a little below hilltops, in small depressions, protected from the sometimes violent winds and storms and from strangers and animals. All the houses are close together, connected by narrow paths. As far as possible, every house has a small kitchen garden with fruit, vegetables and ornamental plants attached or nearby. In the villages there is no division into richer and poorer families, they live mixed together, with pigs, chickens and dogs roaming free in between. There are villages, one part of which is 100 meters higher than the other. The larger villages have a public building, a simple, sometimes only one-room primary school and a church; the Christian village priest and his family live in their own house, as does the clan chief if he comes from the village. In the past, several villages would occasionally come together to defend themselves together; all villages that are not connected are now integrated into the public administration. Many women run a small shop or a tea room with a kiosk in their village. One or two healers (nong ai dawai kynbat) live in each village ; The Khasi know hundreds of medicinal plants , 850 are listed for Meghalaya, over 370 medicinal plants are regularly used as folk medicine by three quarters of the population , mostly collected from the wild. In front of each village there is a small place for the weekly market, depending on the area by a river or under a group of trees. Adjacent is a spacious area with the family graves and in some places very large memorial stones to honor the ancestors ( see below ).

Houses

The typical Khasi house is quite simple and rectangular, with a grass or corrugated iron roof in shell shape and three rooms: the porch ( veranda : shynghup ), the bedroom (rumpei) and in between the larger room for cooking and sitting (nengpei) . Traditionally the Khasi build wooden houses on stilts, nails are undesirable, they are considered taboo ; a leaning wooden ladder leads to the raised entrance area. In addition, a house should have a maximum of three stone walls and the altar in the center may only consist of one type of metal. The buildings of richer Khasi are more modern, with sturdier metal roofs with chimneys, glass windows, and sturdy doors; some have western style houses and facilities .

In the center of every house is the kitchen stove, the lucky location of which is determined with an egg oracle even before a house is built: The shell parts of thrown eggs indicate where the stove should be and whether the whole building project will turn out favorably or not. The hearth forms the social center of the family in the evening, accompanied by stories, songs and music (compare social and religious meanings of the hearth ). In the cool winter time with temperatures around 5 degrees the stove provides the only warmth.

As soon as a house is ready and the family moves in, the house blessing of the ka Shad-Kynjoh Khaskain begins after the ceremony : a ritual initiation dance that lasts from sunset to sunrise.

Village as a community

According to the Khasi tradition, each village sees itself as a community , as an independent social, political and economic unit that administers itself in the village council (through consensus finding ). Village self-government is widespread in India (compare the Panchayati Raj system : self-government by five councilors), but in the tribal state of Meghalaya it has a state-recognized form: Here, each village community usually includes members of four to six different clans (associations of large families ) who see themselves together as an in- group , with a strong sense of togetherness and sometimes their own language dialect and traditions. Village leaders usually become men (see below on village political structures ). If possible, marriage takes place within the village, but in any case outside of one's own clan (see below on marriage rules ). Most of the Khasi live in their village for life, most of the villages have existed for centuries, and their location is very rarely changed. Village solidarity often precedes clan solidarity; as a community , farming, irrigation or trade projects are implemented; earlier could also to military raids or assaults (raids) unloved neighboring villages belong.

"Cleanest Village in Asia"

Khasi villages have a reputation for being some of the cleanest in Asia; the residents keep them well-kept and return frequently in the dry season (November – February). They refer to the Khasi tradition, according to which purity comes its own beauty. The wild growing " broom grass " is widespread across the country in the mountains and hills , some Khasi villages practice the traditional (art) craft of broom binding and cultivate various suitable plants.

The small mountain village of Mawlynnong 90 km south of Shillong in the southeastern Khasi Mountains received the award as “cleanest village in Asia” and in 2005 as “cleanest village in India” (by the travel magazine Discover India ); In 2004 a report by National Geographic made the village famous. The Khasi tribe of the War-Jaintia, who are also famous for their root bridges over jungle rivers, live in this area near Bangladesh . In the allegedly 500 year old village, each of the almost 100 households has running water with their own toilet. In front of each house there is a handmade funnel-shaped waste paper basket made of bamboo, which has become a village symbol. Mawlynnong sees himself as "God's own garden" (God's own Garden) , plastic bags and throwing away garbage and smoking are prohibited, recycling is part of everyday life. The entire village community participates in a state funding program for rural areas , the incomes of the ancestral families have doubled in 15 years, reading skills have increased to 94% (Khasi average: 77%). Besides betel nut palms (areca nuts) and betel leaves ( paan ), broom grass is also harvested and processed here; daily sweeping is part of the village project; As in many Indian villages, the paths between the well-kept houses are made of weatherproof concrete sidewalks. They form a contrast to the stone-paved jungle path that meanders to the centuries-old root bridge.

Names sung

About 30 km north of Mawlynnong is the Khasi mountain village of Kongthong , which is about the same size and is known for its peculiarity of giving each baby a melody as an additional "name". An abbreviated version is used to address the person and can be heard as a sung call throughout the village. The members of the around 100 ancestral families communicate accordingly in the surrounding jungle forests when the air is filled with the sounds of nature during the rainy season. This centuries-old tradition is dedicated to the mythical founder of the respective clan and is called Jingrwai Lawbei : "Song of the Great Mother" of the clan (see below for the worship of the clan founder Lawbei-Tynrai ). This custom can also be found in eleven neighboring villages (see below for peculiar Khasi names ).

Sacred forests

More than 100 Khasi villages have set up a sacred forest in their area, often with memorial stones for the ancestors and places of worship for the protective deities of the village (compare sacred grove , burial forest ). These forests are protected and preserved as an expression of the closeness to nature of the religion Niam Khasi , any extraction of forest products is forbidden and annoys the local deities and nature spirits . 105 sacred groves are officially recognized in Meghalaya under local names such as Law Niam (religious), Law Lyngdoh (priestly) or Law Kyntang (village), [List:] almost all of them are in the Khasi area (with other names in the Jaintia area) . The holy forests have 58 springs , important for the village or urban water supply; Dozens of other forests are waiting to be registered. In the last decades the village communities have been trying to enlarge these natural forest reserves with growing environmental awareness , combined with the demand for financial support for the urgently needed reforestation . The holy Khasi forests are internationally respected as soil improvement ( melioration ) and as species protection for the many native plant and animal species and their migratory corridors ( biotope network ). But with a total of 10,000 hectares , the small forests form only tiny patches within the already two-thirds deforested area of Meghalaya.

In addition to the hundreds of medicinal plants that the Khasi garden, collect and regularly use (850 are listed for Meghalaya), there are many plants that are used in religious ceremonies. A study from 2017 lists 35 different plants with their meaning and exact use in religious activities and emphasizes the species-protective effect of the respect for plants by the Khasi. Many of these plants are grown in the kitchen gardens close to the house, most of them grow naturally in the sacred forests and preserve biological diversity ( biodiversity ).

Root bridges

The long-lasting and very productive monsoon rains cause a huge swelling of mountain streams and rivers in the up to 2000 meter high mountains between March and November, temporarily preventing them from crossing and individual villages are cut off from the exchange of goods for months. A tribe of the Khasi in particular has found solutions for these changing water levels in order to build on the forces of nature with little effort: The War-Jaintia of the southern Khasi mountains let the aerial roots of the Indian rubber tree (Ficus elastica) through bamboo poles or hollowed trunks of the betel nut palm grow from one side of the narrow gorge to the other. After 15 years, the plants begin to form a stable connection across the water. Sticks, stones and pounded earth are tied into the growing network of roots in order to obtain a “ living bridge ” that will endure centuries (compare the research field of building botany ). Continuously nurtured and strengthened, these elastic structures withstand the violent storms and occasional earthquakes in the region without major damage. They also offer wild animals opportunities to move around and are said to last for up to 500 years. The two-story bridges in places, together with the highest waterfalls in India, are among the sights of the southeastern Khasi and Jaintia mountains in the border area with Bangladesh.

Khasi economy

Most Khasi extended families ( iing ) work in the manner of a family business and form overarching associations in the manner of agricultural cooperatives , especially in the village communities ( see above ). Around 1800 documents of the British East India Company describe the Khasi as a very experienced market-oriented people, with a stable economy consisting of the three elements of land ownership, field work with production and trade in the many local markets.

Many families do farming as demand economy ( subsistence ) and use different types of traditional field construction ( Pflanzbau ) and can be combined manageable livestock with some pigs, native cattle, goats, chickens or bees and perhaps a small village shop. The main food of the Khasi is cooked rice, vegetables and eggs, meat or (dried) fish; Legumes and nuts are not common. There are some food taboos , so cow or goat milk may not be drunk. The main vegetables grown are potatoes, sweet potatoes , cabbage and, increasingly, tomatoes, while the fruit is mainly the sweet khasi mandarins , pineapples and bananas, distributed in different altitudes. On the plateau, the kitchen gardens with vegetables, spices, medicinal plants and orchids are protected by small walls and hedges. There are a few villages with small industries such as cutlers, otherwise there is very little industrial production in the Khasi area. The proliferation of the sewing machine has made it possible to mass-produce garments at home, but increasingly cheap plastic is replacing traditional weaving.

Land ownership

The entire land of a village and its individual extended families is regulated in the manner of a cooperative or cooperative and administered by the village community or its village council: There are around 30 different types of land ownership in a village, some relate to common areas and common areas (village land) or collective and co-ownership , other land areas are inherited only within individual family lines ( see below ) and others relate to newly developed or privately acquired properties. Over the centuries, locally different systems with stable traditions have developed in order to guarantee the well-being of the resident families and to hold together the basis of economic activity for the entire village (compare agricultural community ). All villagers have equal access to the cultivation of the communal land (for self-sufficiency ), not differentiated according to social prestige or wealth. The village community can lease land or rights of use to outsiders (transfer of use), for example for a private plantation or animal farm or for the extraction of mineral resources. In 2011, around 82% of all houses in Meghalaya were owned by the owner, only 16% were rented out. A 2003 government survey of household land ownership in India found that the Scheduled Tribes owned slightly more households than the Indian average, and that each tribal household owned slightly more land than the average (0.70 hectares at 0.56 per household).

Conflicts:

- A comprehensive study of 2007 on the question of social security within the Meghalaya tribes came to the conclusion that the way in which Khasi land is dealt with is changing noticeably: Increasingly, parts of the village and family land are becoming private property, especially Khasi men are becoming new landowners (non-indigenous people are prohibited from buying land in Meghalaya). This weakens the economic foundations of the families and villages, in addition to the overexploitation of the remaining common land (compare the tragedy of the commons - the tragedy of the anti-commons ). Many families see themselves being forced by the privatization to switch to less productive areas, which in turn increases the harmful effects of their slash-and-burn agriculture ( see below ). As the owners of the (family) land, women are exposed to growing social insecurities; Increasingly, women cannot offer a desired husband any social security to start a family, which in turn increases the desire of men to own their own land. Across India, too, the proportion of land ownership fell among the 705 registered tribes (Scheduled Tribes): in 2001 45% of tribesmen worked on their own land, in 2011 it was only 35%, while the proportion of tribesmen who worked on foreign land , with 46% remained the same.

Fishing

In the southern foothills of the mountain ranges, the monsoon water masses run off in numerous small and large rivers and at times form crystal clear lakes, the network of water bodies is very rich in fish and species. The village communities have always drawn up binding rules for their area, set catch quotas and issue fishing bans during the spawning season in order to preserve the sustainability of the economic basis of their community . Meghalaya's government has set up funding programs and banned chemical and blasting aids that were used in other places.

In the southern Khasi Mountains, the Khasi tribe of the War use their own traditional methods of fishing with techniques and devices for different types of water, seasons and animals for self-sufficiency. For the war, edible fish and other aquatic animals are the main source of their protein , along with meat ; if the catch is dried within hours, it can be stored for a few days. Edible aquatic plants are also collected or harvested at the appropriate time. There are six different plants that are used to stunning animals, so a juice of berries, which is poisonous for fish, is put into the running water of a river, then the stunned fish are collected downstream (compare fishing with plant poisons ). Eleven plants are used as bait for different types of trapping, differently woven bamboo baskets serve as traps , and some frog species are caught. These traditional and cooperative forms of management protect the fish population and demonstrably preserve the biological diversity of the many bodies of water.

Farming

The Khasi Mountains consist of many chains of hills with a large plateau crossed by valleys and gorges at 1500 m , on which Shillong is also located. In the south this open, very humid plateau drops steeply towards Bangladesh, accompanied by many waterfalls. For up to nine months between March and November, tropical monsoon rains soak the wet and rainforests of the mountains and hills. The jungle merges into extensive areas with shrubbery and scrub , on the plateau there are smaller grassland areas.

The Khasi cultivate four different types of land:

- extensive forest and jungle areas in the hills to collect, for traditional agroforestry and for alternating slash and burn shifting cultivation (shifting cultivation)

- Local grassy areas on the plateau, especially for corn and millet ( food crops for self-sufficiency)

- Moist areas, especially for private rice cultivation, mainly in the southeastern neighboring Jaintia area ( cash crops for sale)

- small field and kitchen garden areas near the house for mixed cultivation (various fruit, vegetable, aromatic and ornamental plants )

Accordingly, the village communities have specialized in the management of their respective natural surroundings and thereby developed differences in way of life and traditions, right up to their own language dialects (compare ecosystem people ). At the same time, the differences in cultivation have led to intensive trade, even between distant villages, which forms one of the three pillars of the Khasi economy (alongside land ownership and field work).

Conflicts:

- There is a sustained population explosion in Meghalaya (annual increase of over 2.5%), so the total population grew from 1.33 million in 1981 to just under 3 million in 2011 (+122%). This led to major problems early on because the available cultivation areas in the mountain and hill areas are limited; Hardly any more can be developed and new jobs can be created. Agriculture accounts for 70% of the overall economy, but more and more Khasi families can no longer get (new) land ownership; their relatives have to seek their happiness in wage labor, mostly low paid. Already in 2001 poverty had risen considerably in the whole of Meghalaya, whereas the government set up appropriate subsidy programs; In 2011, 11% of the total population lived below the statistical poverty line . The growth rate of the population in the six Khasi administrative districts corresponded to the national average of almost 3% annually, 78% of the Khasi lived in the countryside; the share of the Khasi in the population had fallen from 56% in 2001 to 48% (see table of population data ). The population of Meghalaya is expected to grow to 3.77 million in 2020.

Broom grass

In the mountains and hills grows the " broom grass" , a sweet grass of the Amriso species (Thysanolaena maxima) , which can be found at altitudes of 1,800 meters and which holds together the most varied of soils with its dense roots. Amriso is also funded by the International Climate Initiative (IKI) as an adaptable, promising plant, the German Environment Ministry supports an initiative in the nearby mountainous state of Nepal , which is similarly endangered by landslides and frequent earthquakes . Harvesting, planting and selling of the broom grass has been promoted by the Meghalaya government since 1995, after corresponding products were presented at a trade fair in India's capital and were in great demand. In 2000, an initial survey showed that 40,000 families benefit from the broom grass and its processing. Although the buying middlemen earn the same amount from the products, the broom grass enables the families to earn additional income, especially in the low-income winter season. It also offers an alternative to harmful hiking slash and burn ( see below ) and is increasingly being grown on a plantation basis as cash crops for sale. The traditional (art) craft of broom binding is widespread and is pursued by whole Khasi villages and specifically cultivating various suitable plants. Across India, 250 million households buy two new brooms every year, preferably made from broom grass.

Slash and burn

In the wooded hills, the field construction of the Khasi conditionally changing fire clearance for the acquisition of new acreage ( hiking Pflanzbau ), in Asia generally considered jhumming known (see the trunks of Jumma ) or slash and burn cultivation (Hack-and-fuel cultivation ). To this end, at the beginning of the four-month dry season in November, the entire village community decides to cut down a limited area, sometimes an entire hilltop or flank. Mostly the areas are on steep mountain slopes. All vegetation is chopped off and left for a few weeks so that it can dry out in the sun before the remains are burned off in a controlled manner. The remaining trees and rhizomes are also set on fire. The ash provides minerals to the soil and makes it more fertile. Without plowing beforehand , the seeds are sown at the beginning of the new rainy season in March, which means that no irrigation is necessary. The cultivation by the individual families follows the division of the land as determined by the village community. Normally, an area with annual crop rotation is used for three or four years, then it remains fallow land for various slow-growing crops and a new jhum area is opened up ("hiking cultivation"). 40% of the area of Meghalaya is cultivated by shifting cultivation .

The jhumming requires many hours of work, the effort can only be done collectively; in Meghalaya around 52,000 families depend on it. For centuries, this farming method has preserved the protective vegetation of the hills and mountain flanks because the village communities did not want to "exploit" their own lands, but wanted to cultivate them sustainably. The shifting cultivation is the optimal local adaptation to the violent monsoon rains meant affected hilly areas to organic pure a variety of crops for self-sufficiency to grow (sometimes up to 30 simultaneously). Slash-and-burn clearing is generally decreasing because its yield decreases, because the damage caused has lasting effects on the entire habitats ( biomes ) of the village communities.

Conflicts:

- The time intervals between clearing and slashing in the same place used to be 15 years or more, during which the soil and its protective vegetation could recover - the change is becoming increasingly shorter, sometimes to less than 5 years. For decades, this overexploitation has led to severe soil erosion ( soil degradation ) because there is no vegetation to protect the soil and to store the monsoon rain masses ; the running water washes the fertile topsoil down into the valley, while other watercourses seep away . To counteract this, university-trained Khasi have successfully introduced new cultivation methods, including stationary terrace cultivation. The government programs recommend above all a switch from shifting cultivation to plantation-like cash crops for sale, for example broom grass, which with its strong roots can hold together even eroded and depleted soils and very quickly produces a lot of biomass . Plantation cultivation, however, requires a fundamental change from traditional, mixed cultivation methods to monocultures , with all the known disadvantages such as high investment costs, the inevitable use of chemical fertilizers and poisons and the elimination of self-sufficiency. Increasing plantations also do not replace the necessary protective vegetation and prevent the possibilities of traditional, mixed agroforestry . In addition to cash crops, the government supports the establishment of protected areas and sacred forests modeled on the Khasi ( see above ).

- The Garo Mountains to the west are particularly affected by deforestation , where international projects with alternatives to slash and burn are running with the willing participation of the village communities. In the Garo Mountains, it is the wildlife that suffers, the number of elephants living in the wild has fallen to less than 1000 (in 2008 there were still 1811 elephants in Meghalaya), and the number of gibbon apes has more than halved. Here the matrilineal Garo adopt the Khasi tradition of natural forest reserves ; these should also ensure the elephants' migration corridors .

trade

At the beginning of the influence of the British East India Company from 1750, the Khasi still conducted extensive trade with their neighboring peoples, in the east as far as Cambodia - their Mon- Khmer language is related to Cambodian , from which their original origin is assumed ( see below ). Some time later, as part of their advancing conquests, the British imposed a comprehensive boycott of all Khasi goods, which led to growing resistance from the chiefs in the border areas. In the peace negotiations that began in 1860, the chiefdoms were granted tax exemptions and self-government, and the Khasi’s extensive trade flourished again. The British colonial rulers were impressed by the economic and trading skills of the Khasi, but they were dependent on cross-border exchanges. Even today, almost all of the extended Khasi families trade in excess crops or specially made products, are middlemen or intermediaries, or run a shop.

Conflicts:

- The nationwide Khasi trade is limited in the south by the generally closed border with Muslim Bangladesh (420 km long); around 100,000 Khasi also live there in the large Sylhet district . Until 1971, an extensive trade network spanned between the Brahmaputra River in the north, the Khasi Mountains and the large area of the Ganges in the south, mainly via markets along the main highway between Calcutta via Shillong to Guwahati , still built by the British occupiers (cf. the National Highway 40 ). The third Indo-Pakistani war brought this network to a standstill. In 1972 the state of Bangladesh split off and became independent, border traffic was hardly possible any more, and the whole of northeast India was cut off from access to the Indian Ocean . The exchange of goods remained difficult for decades, and the Khasi could no longer trade their coveted khasi mandarins (original type), betel nuts (areca nuts) and betel leaves ( paan ) as well as their rich mineral resources (coal and limestone ) to the south. Although the border is still impermeable, around 90% of the export of khasi mandarins went to Bangladesh in 2015, while trade connections to northern India are generally low and only run through a narrow bottleneck via West Bengal .

- The abundant uranium deposits in the southwestern Khasi Mountains (9 million tons) have been withdrawn from trading because the valuable metal is only exploited by the Indian government, without any influence on the part of the authorities (India is a nuclear power ). This fact and the widespread environmental damage caused by toxic uranium mining have become a public issue in Meghalaya, which the three most important Khasi organizations also use ethno-centered arguments under the heading of “foreign infiltration” ( see below ). In 2018, the dispute over illegal coal mining in the form of "rat hole mining" on the Khasi area also played an important role in the election and the subsequent formation of a new government (see coal mining in Meghalaya ).

Weekly markets

Markets take place alternately in the many villages, on a specially prepared market place on the edge of the village near the memorial stones . The frequent weekly markets fulfill not only economic but also important social tasks, they enable the constant exchange of information, serve as a marriage market and sometimes organize sporting competitions. The most popular is archery, of which the Khasi are particularly proud of its distinctive tradition (see below for archery ). The largest market is in the middle of the Khasi area in the capital Shillong (at 1500 m ): Police Bazar occupies an entire district, is open daily and attracts visitors and traders from the wide plateau and the surrounding Khasi mountains.

Gender specific data

Meghalaya is the only ( federal ) state in the world with an officially matrilineal society (maternal lines), both the Meghalaya government and the Indian Union government emphasize this matrilineal society , whose parentage rule and family affiliation is anchored in the constitution. In 2011 the Khasi had a share of 47.6% of the total population, the Garo 27.7% (together 75.3%). Both are recognized as Scheduled Tribes and together made up 87.4% of the 17 tribal peoples in Meghalaya, who in turn made up 86.2% of the total population; In India there were a total of 705 recognized Scheduled Tribes in 2011, with a share of 8.6% of the population of India (1,210,855,000).

The following lists from 2011 compare the data from Khasi, Garo, Meghalaya, Scheduled Tribes and all of India - broken down by women and men and their proportions in the total group. For example reading ability: 77% of the Khasi can write, for women it is 79% (all ♀ from 7 years), for men only 76% (all ♂ from 7 years); There are 448,600 female alphabets and 411,200 male alphabets, so the total number is divided into 52.2% women and 47.8% men: 4.4% more Khasi women than men can write. This breakdown is calculated below for the employment rates, gender distributions and literacy rates. Then various metrics for wealth and gender equality are listed.

Employment rate

86.1% of the inhabitants of Meghalaya 55.2% are Khasi (48% of the inhabitants) 32.1% are Garo (28% of the inhabitants)

Nowadays, Khasi are increasingly pursuing a modern career or studying at one of ten universities such as the North Eastern Hill University in Shillong, founded in 1973 (about 150,000 inhabitants). Their families keep a few animals for self-sufficiency and cultivate their own garden areas ( horticulture ). Since 82% of all houses in Meghalaya are owner-occupied and all villagers have equal rights of use to the community land ( see above ), there is only a low official unemployment rate of 4.8%. In 2012, 11.9% of the population in Meghalaya lived below the poverty line (less than 890 Indian rupees per month in the countryside or 1150 in cities), while it was 21.9% throughout India (816 rupees per month in the countryside, 1000 in cities ).

2011, the official calculated employment rate in India the ratio of the number of employed persons (workers) to all other residents:

| Employment rates 2011 | |

|---|---|

| Khasi (48% of the population, 55% of the tribes) | Garo (28% of the population, 32% of the Tribes) |

|

40.2 % , of which 59% in agriculture ♀ 34.4% of women: 43.5% of those in employment |

40.0 % , of which 72% in agriculture ♀ 35.4% of women: 44.1% of the employed |

| Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (86% of the population) | ST in India (705 recognized: 9% of all population) |

|

40.3 % , of which 64% in agriculture ♀ 34.9% of women: 43.6% of those in employment |

48.7 % , of which 79% in agriculture ♀ 43.5% of women: 44.4% of those in employment |

| Meghalaya (3 million inhabitants) | India (1.21 billion inhabitants 2011) |

|

44.3 % (2001: 49%) ...% of women: ... |

39.8 % , of which 55% in agriculture ♀ 25.5% of women: 31.1% of the employed |

The Tribes employment rate in Meghalaya was the 4th lowest of the 29 states in India at 40% .

Worldwide, the rate is calculated the proportion of workers from all working people in the age of 15-64 years, in 2018 the average of the 36 member states was the OECD at 68.3% (60.8% in women and 76.0% for men ), in India 2012: 53.3% = 27.3% for ♀ and 78.5% for ♂ (compare India in the list of global employment rates ).

Sex ratio

Number of male babies up to 1 year in relation to 100 female

Meghalaya: ≈ 104 ♂ to 100 ♀

The gender distribution in India was officially calculated in 2011 according to the number of women in relation to 1,000 men; among the Khasi this was ♀ 717,000 to 695,000 = 1,033 women to 1,000 men. The Khasi have no relation to gender preference, which is practiced through abortion of female embryos in large parts of India and China - this shows the number of girls under 7 years in relation to 1000 boys (together 21%):

| Gender relations 2011 (2001, 1991) | |

|---|---|

| Female relatives per 1000 males | Girls per 1000 boys (together ≈ 20%) |

| 1033 ♀ with the Khasi (1017) | 971 ♀ with the Khasi (979) |

| 988 ♀ with the Garo (979) | 976 ♀ at the Garo (...) |

| 1013 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (1000) | 973 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (974, 991) |

| 990 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in India (978) | 957 ♀ at Scheduled Tribes in India (972, 985) |

| 989 ♀ in Meghalaya (972; 1901: 1036) | 970 ♀ in Meghalaya (973, 986) |

| 943 ♀ in India (933) | 914 ♀ in India (927, 945) |

| 984 = global average | 935 = global average |

In 2011 Meghalaya was 6th in India, 1st: Kerala with 1,084 females to 1,000 males; for children, Meghalaya was in second place with 970, behind Arunachal Pradesh with 972 girls to 1000 boys.

The sex ratio of male to 100 female residents is measured worldwide; in 2015 it was 102 ♂ (107 ♂ babies to 100 ♀), in India: 107.6 males, at birth: 110.7 boys per 100 girls .

Literacy rate

Meghalaya | Women | Men | Card

all: 74.4% 72.9% 76.0% Khasi: 77.0% 78.5 % 75.5% Garo : 71.8% 67.6% 76.0%

Meghalaya | Women | Men

2001: 62.6% 59.6% 65.4%

1991: 49.1% 44.9% 53.1%

1981: 43.2% 38.3% 47.8%

1971: 35.1% 29 .3% 40.4%

1961: 32.0% 25.3% 38.1%

1951: 15.8% 11.2% 20.2%

The reading ability was calculated in India in 2011 for all persons aged 7 years. Among the Khasi, the 3% higher reading rate rate among women compared to men (4.4% more women can read) clearly stands out from the national and India-wide differences between the sexes. The rate shows how much girls' schooling is valued by the Khasi - also in contrast to the neighboring matrilineal Garo, although they have a particularly balanced gender ratio (50.3% of the 820,000 Garo in Meghalaya are male), but 6, 4% more men than women can read, the female literacy rate is 8.4% lower than the male:

| Literacy rates 2011 (2001) | |

|---|---|

| Khasi (48% of the population, 55% of the tribes) | Garo (28% of the population, 32% of the Tribes) |

|

77.0 % (66%) ♀ 78.5% of women: 52.2 % of the alphabets

♂ 75.5% of men: 47.8%

|

71.8 % (55%) ♀ 67.6% of women: 46.8% of the alphabets |

| Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya (86% of the population) | ST in India (705 recognized: 9% of all population) |

|

74.5 % (61%) ♀ 73.6% of women: 50.0% of the alphabets |

59.0 % (47%) ♀ 49.4% of women: 41.8% of the alphabets |

| Meghalaya (3 million inhabitants) | India (1.21 billion inhabitants 2011) |

|

74.4 % (63%; 1951: 16%) ♀ 72.9% of women: 48.8% of the alphabets |

73.0 % ( 65% ; 1951: 18%) ♀ 64.6% of women: 43.0% of the alphabets |

Worldwide reading ability is measured from the age of 15; in 2015 it was 86.3% (82.7% for women and 90.0% for men), in India: 71.2% = 60.6% for ♀ and 81.3% at ♂ (compare India in the list of global literacy rates ).

Indices

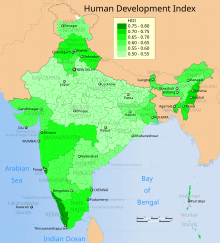

HDI India: 0.605

Meghalaya : 0.629 (see map)

2006 - United Nations values :

HDI India: 0.544

Meghalaya: 0.543 ( HDI list of the UNDP )

per capita in India ( world list )

Meghalaya low 2014: Meghalaya in 20th place

Human and Gender Development

As a benchmark for prosperity and gender equality in the countries of the world, the United Nations Development Program UNDP calculates several statistical indices annually (key figures with values from a low 0.001 to an optimal 1,000):

- HDI Human Development Index " Human Development Index " = average life expectancy , years of schooling and purchasing power per capita (officially from 1990)

- GDI Gender Development Index " Index of gender-specific development " = HDI values of women and men in relation to one another (officially from 1995)

- GEM Gender Empowerment Measure " Women Participation Index " = political and economic participation and income, separated by gender (1995-2014)

- GII Gender Inequality Index " Index of gender-specific inequality " = reproductive health of women, proportion of women in parliament as well as school education and labor force participation in a gender comparison (from 2010)

Both the Meghalayas government (planning department) and the Indian Union government (ministry for women's and child development) have made their own calculations based on UNDP calculation methods, some with different values. They serve as a planning basis for improvement programs; the respective ranking can refer to the 29 states of India or also include the 7 union territories . The HDI of the total of 705 Scheduled Tribes is calculated as a low 0.270 (unchanged since 2000).

- 1991: HDI from Meghalaya in 18th place with 0.464 (India: 0.432)

- According to Meghalaya's government: Rank 24 with 0.365 (India: 0.381) , and the former

- GDI Gender Disparity Index: Rank 7 with 0.807 (India: 0,676).

Both governments cite the matrilinearity of society (“due to matrilineal society”) as the reason for this gender improvement compared to the average for India .

- 2006: HDI from Meghalaya in 22nd place with 0.543 (India: 0.544)

- The Union government states: 17th place with 0.629 (India: 0.605) , and the

- GDI Gender Development Index: 14th place with 0.624 (India: 0.590), as well as the

- GEM Gender Empowerment Measure: Rank 28 with 0.346 (India: 0.497) .

- UNDP's GII Gender Inequality Index in 2011 for all of India: 0.617 at 129th place (out of 146 countries)

- 2017: HDI of Meghalaya in 19th place with 0.650 = comparable to Guatemala or Tajikistan (compare also Meghalaya in the India-wide list according to gross domestic product )

- HDI of all Scheduled Tribes remains at just 0.270

- India ranks 130th in the world with 0.640 (2016: 129th) , comparable to Namibia , in the group of countries with " medium human development"

- GDI Gender Development Index: Rank 149 with 0.841 ( HDI 0.575 ♀ to 0.683 ♂ )

- GII Gender Inequality Index ranked 127 with 0.524

In terms of gender, the large Indian state with its more than 1.3 billion inhabitants has low values, mainly due to the low employment and political participation of women (GDI and GII are not known for Meghalaya).

Femdex (2015)

The index called Femdex ( Female Empowerment Index : comparable to the earlier GEM) was calculated by the McKinsey Global Institute in 2015 for the 28 Indian states and the 3 largest of the Union territories. Meghalaya came second with 0.69 (behind Mizoram with 0.70; India: 0.54) , comparable to Argentina , China and Indonesia - while the neighboring Assam had the third lowest Femdex in India with 0.47 (comparable to Yemen or Chad ). Gender equality with regard to work was significantly more pronounced in Meghalaya and Mizoram with 0.56 than in the other states, whereby women in Mizoram were socially better off with 0.87 than in Meghalaya with 0.82 (rank 1: Chandigarh with 0.92) .

Social organization

The Khasi people consists of several tribes and sub-tribes, listed in the 2011 census as "Khasi, Jaintia, Synteng, Pnar, War, Bhoi, Lyngngam" (1,412,000 in Meghalaya state, 48% of the total population). Each tribe is made up of independent clans , each clan consists of many extended families who see themselves as related to one another. These clans form over 60 chiefdoms in the Khasi and Jaintia area (see below for the political structures ).

Large matrilineal families ("houses")

The smallest independent social and economic unit of the Khasi is the 3- generation family, called iing (house, family), respectfully and lovingly referred to as shi iing "a house": a woman with her children and the children of her daughters, that is the extended family of a grandmother with grandchildren . All members of the iing live together or close together in the village community , including the (unmarried) sons and grandsons. This family is managed by the grandmother, in coordination with all adult relatives (cooperative). Often a brother or uncle lives with the grandmother, sometimes a sister or aunt, preferably with offspring.

The following diagram shows an example of an iing , founded by the "mother", to which the family names are related (grandmother from the point of view of her grandchildren):

|

Master mother foremothers (grandmother) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mother brother (great uncle) social father |

" Mother " (Grandmother) Age: 33 ~ 55 |

Mother sister (great aunt) ... has only sons |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sons social fathers |

Youngest heir daughter |

Daughter ... without children |

Daughter elder |

Nephews (cousins) → marriage ban |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grandsons | Granddaughter youngest |

Granddaughters older |

Granddaughters | Grandson ... social father |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... great-grandchild | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Real estate: The house and land, the rights of use and the assets of a large family are exclusively in the competent hands of the "mother", usually managed by her older brother ("mother brother") or her uncle (her social father ), in consultation with everyone adult members of the iing in the form of a cooperative or cooperative as a community of solidarity . The “mother” started her iing with her own kitchen garden and residential house as well as land use rights, for which her descendants developed or earned additional land and rights of use within the village community (see above on village land management ). Your youngest daughter will inherit all of this and in turn pass it on to her youngest daughter (see below for succession by youngest daughters ). If a woman has no daughter, she cannot start an iing because the family would not continue; the woman stays with her mother (perhaps with sons) or joins a sister and her children to support them.

| Data |

|---|

A Khasi woman asks questions at an information event on the measures of Bharat Nirman , the state support program for rural areas (Tynring, eastern Khasi Mountains , Meghalaya, 2013)

|

| Matrilinearity |

|

Northeast India: Khasi, Garo Linearity of all 1267 ethnic groups worldwide: (1998)

1300 ethnic groups are recorded worldwide (2018). |

| Matrilocality |

|

164 matrilineal ethnic groups worldwide - their marital residence after marriage:

1 patri- linear ethnicity out of 584 lives in matri- local. |

| Matrifocality |

|

Matrifocality = "matrifocussed, matrix-centered" " Matriarchy " = Latin. "Rule of the mother" History of matriarchal theories = |

| Matriarchy? |

-

Identical descent: All shown relatives are related by blood , they are all descendants of the same woman: the mother of the "mother" (from the grandchild's point of view: the great-grandmother ). In their understanding of consanguinity, the biological fathers of the relatives play no role, they do not belong to the iing . This extended family also does not include the children of brothers, sons or grandchildren - like biological fathers, all children of male family members belong to the extended families of their own mothers. The family shown is therefore not a whole, but half an extended family (only 1 of the 2 parental lines of descent ): The sons of all generations inherit the family and clan names from their mother, but cannot inherit them, and sons cannot pass them on Inheriting property, title or privilege from her mother (and neither from her father).

This restriction to the parentage is technically called matrilinearity : "in the line of the mother", and is found in around 160 ethnic groups and indigenous peoples worldwide . Such a line of mothers goes back over the biological foremothers to an ancestral mother (sometimes just to say " haft" ), who is revered as the founder of the entire line ( see below ). In contrast, there are families of other peoples who derive their descent only from the father and his forefathers ( patrilinearity : “in the line of the father”); with some peoples children inherit certain affiliations and positions only from the mother-side, others only from the father-side ( bilinearity , example: Jewish religion from the mother - Jewish ethnicity from the father).

The Khasi also know forms of joint adoption : After adopting an unrelated person “as a child”, this person becomes a member of the family of the adopting mother and receives her clan membership.

- Social fathers: All brothers care for the children and grandchildren of their sisters, in all generations (see below for the meaning of mother brothers and their social fatherhood).

- Husbands: With the women of the iing "married" husbands can live as supporters of the whole family - but they are not members of the "house" because they are the sons of other iing to whom they belong. The married men of the family (brothers, sons, grandchildren) are absent, they live in the families of their wives, as married supporters; their biological children also belong there (see below on the place of residence with the mother ). Since all husbands are also social fathers for their own siblings, the biological children of a husband always have a social father, often several (see below for the family roles of men ).

Advantages of the matri- linear extended family:

- The “mother” first took care of her children and does the same for the children of her daughters (the eggs of the daughters have already arisen in the womb of the “mother”). With the accumulated economic assets of the family, the “mother” now also ensures that her grandchildren can raise their needs and can look after them. This support of a mother by her mother is seen as a human evolutionary advantage because it measurably improves the survival chances of the grandchildren - in comparison to other primate species and also to the patrilineal families, in which the wives live fundamentally separate from their mothers and often from the mother of the husband must subordinate (compare findings on the importance of the maternal grandmother ).

- The power of disposal over the economic assets in the hands of only one group mother guarantees the protection of all relatives, including those unable to work: children, the sick, the disabled, the disabled and the elderly of several generations. This means that all men and women are covered as members of their mother or sister family. All of your interests in this social security act as a control over the group mother and her advisory brother or uncle not to endanger the group's assets through stubborn decisions or interests. The extended Khasi family sees itself as a community of solidarity in the form of a “ social insurance ” to which all relatives “pay” their available labor and income.

Matrilinear lineages ("bellies")

At the latest with the birth of the “great-grandchild” indicated in the diagram, his grandmother (the “older daughter”) will consider moving out. With her husband, a brother or uncle as well as her children and the husbands of her daughters, she will now found her own iing , a new “house” (compare also aristocratic / ruler “house” and differences between “house, family, family gender ” ). Then the “mother” “produced” a new, independent extended family from her own womb : a grandmother with granddaughters. She is now great-grandmother, probably about 50 years old, and has as an experienced family manager her family successfully managed - in close cooperation with the many other branches of the family of their line and the other clan families in their community.

With the departure of the "older daughter", the remaining extended family has grown to become the next largest social unit of the Khasi, a self-confident kpoh , literally "belly, womb", technically lineage : a "single lineage group" with at least 4 living generations, followed by the Khasi tracing back to the line of her mother, her mother, and so on (mother line). Worldwide there are individual families with 6 generations, the Guinness Book names 7 as a world record: a line through 6 generations of women from 109-year-old great-great-great-great-grandmother Augusta Bunge to her newborn biological great-great-great-great-grandchild in the USA in 1989 (compare generation names ). The diagram of a living Khasi great, great, great grandmother would show over 200 members of her 6 successor generations.

This lineage, respectfully referred to as shi kpoh “one belly” (one lap, united, united), is continued by the heir and then her youngest daughter, and with each “older daughter” in each generation, new iings are found. The extended family of the older daughter, who moved out, will in turn grow into a kpoh a generation later , a lineage of its own (also known as a “subclan”). Khasi women are generally not viewed as inferior if they have no children, or only sons, or if they do not feel called to start their own home - their support and security are welcome in a sisterly household.

The designation of such large family groups as " clan " is imprecise and out of date, it refers to the old Germanic tribes ; The designation as “ gender ” (succession according to the “ male line ”) is also reserved for the patri- linear large families . The designation of a lineage as a “clan” is also wrong, because such a group sees itself as a superordinate association of many individual lineages, which derive their commonality from ancestry, a local origin or other identity-creating references (compare also totemistic clans ).

Ancestor worship

The original founder of a kpoh is revered as "the old grandmother": ka Lawbei tymms . This ancestral mother is asked for protection against suspected external negative influences on the whole family with ceremonies and offerings . The worship of ancestors, or ancestral cult in technical terms , is a natural part of the Khasi 's worldview: The foundress' remembered powers extend to the present day and are often implored to ward off unwanted forces from the surrounding nature or from other people. For her part, the kpoh founder is seen as a blood-related descendant of the original "Basic Great Mother" of the entire line, the ka Lawbei-Tynrai (lawbei: great mother; tynrai: fundamental; see above about sung names ). In the course of centuries hundreds of blood-related lineages may have outgrown the ancestor's "belly" (kpoh) - she will be honored in memory by all of her descendants. This presence of the common ancestors has the effect that all of these descendants feel that they are “siblings” with one another and share a solidarity that distinguishes them from the descendants of the other Khasi ancestors (see culture of remembrance ). They see themselves as members of a large family and form a “ clan ”, in the manner of an interest group , with all kpoh members as “subclans”.

In addition to the respective kpoh ancestral mother, her (then) husband is also honored and asked for assistance: u Thawlang , as “the first father”, can provide spiritual help, especially in disputes within the family. The eldest brother of the ancestral mother is even more venerated than u Suid-Nia: “the first uncle” (mother's side). It is often found as the largest of the three upright memorial stones (mawbynna) , some of which can be several meters high (comparable to megaliths ). The upright stones represent the male ancestors who protect their sisters and nieces lying down. There are no tombs , but memorials of honor that are visible from afar, comparable to the old European menhirs (see pictures ).

Residence with the mother

Khasi follow their traditional marriage rules , which prohibit marriage within their own clan and can punish them with the final repudiation of the couple (see below on the religious incest taboo ). This general rule of exogamy (outside marriage) initially prevents incest , since all groups of ancestry within a clan ( kpoh , iing ) are blood related to one another through branching maternal lines - or at least are considered to be physically related. Proceeding serve exogamous marriage regulations' need genetic mix by systematically avoiding similar heritage within his own clan. In addition, marriages between clans often serve to promote social fraternization or the political alliance of clans (formation of alliances). Most clans around the world only marry members of other clans, some of them were formed solely for this reason. Marriage partners must be sought in the extended families of other Khasi clans, including the children of the mother's brother or mother's uncle, because these cousins do not belong to their own clan, but to the clans of their mothers (compare the ethnological term of cross-cousin marriage ). Before a planned marriage, the mothers of the bride and groom will check carefully whether the two had a common ancestor in the distant past . This rule of exogamy is restricted by opposing endogamous do's and don'ts (internal marriage): Marriage within the Khasi village community is welcome ; In many clans, non-Khasi spouses are not welcome, and in recent times men have even threatened to punish them ( see below ). In the border areas there is a tolerated exchange of marriage partners with neighboring indigenous people ( see below ).

In the middle of the last century, Khasi women mostly married between the ages of 13 and 18 and men between 18 and 35; now there is a legal minimum age of 18 for women and 21 for men. In 2001 the census of marriages among Khasi (with Jaintia) and the small group of Synteng (1,300 members) showed :

- 63.4% unmarried (highest rate of Scheduled Tribes in Meghalaya)

- 30.9% married (lowest rate of tribes)

- 3.2% widowed

- 2.5% divorced / separated (highest rate of tribes)

- 1.4% of the girls under the age of 18 had married (lowest rate of Tribes; highest: 1.8% for Synteng)

- 1.3% of men under the age of 21 had married (1.5% among the Synteng: highest rate)

In order to choose a husband, a woman must either offer social security as an inheritance daughter through the property of her mother family, or as an “older daughter” the possibility of being supported by her mother family. The youngest daughter will never move out of her mother's house, the future daughter must move in with her; older daughters have more freedom and can, in the course of time, set up a new residence with their husband near the mother's house.

In general, the desire for contact is made by the women, and the local weekly markets also serve as a marriage market . The young men like to come here or they proudly present themselves to the assembled ladies at the monthly celebrations and festivals of the Khasi calendar. At wedding celebrations , ritual gifts are exchanged between the two families, such as the widely appreciated betel nuts and betel leaves . Bride price payments or a morning gift from the husband do not exist with the Khasi, nor does the dowry system of dowry , which is widespread throughout India , in which husbands demand high dowry from the bride's parents (compare dowry murder ). The spouse's clan is respectfully referred to as kha (comparable to a brotherhood ), while one's own clan is affectionately referred to as kur . According to both the Khasi tradition and its Christianization, the Khasi lead marital relationships monogamous (“unmarried”). A divorce was traditionally quite easy and could be initiated by the woman, even today the divorce rate among the Khasi is slightly above the Indian average. There are hardly any “ single parents ” Khasi mothers and the problems associated with them, since at least female family members live in the house, and the older brother or uncle is important for the mother and her child.

The chosen husband has so far supported his own mother family and worked for her - now the wife expects that he will move in with her and her extended family and support her and the planned children. This choice of marital residence is technically called matrilocality : “at the place of the mother”. In the evaluation of all around 1,300 data sets on ethnic groups and indigenous peoples worldwide, matrilocality is found in a third of the around 160 matrilinear cultures, even more prefer an avunculocality : the marital choice of residence with the wife's mother's brother (her maternal uncle). In the case of a wife who is not entitled to inheritance, a place of residence “in a new location” ( neolocal ) has recently been increasingly considered, whereby job opportunities in cities play a role.

Since a wife is normally covered by her mother's family, she is not necessarily dependent on the presence and work of her husband, in some cases the husband is mainly with his own extended family, both spouses remain "at the place of their birth" ( natolokal ) . Earlier ethnologists ( ethnologists ) reported observations made by the Khasi tribe of the Jaintia ( Synteng / Pnar), that the husband stayed at his mother's place of residence and visited his wife only occasionally, mostly overnight. In 1952, the German priest and ethnologist Wilhelm Schmidt advocated the thesis of a “ visiting marriage ” as an “even older form of maternal right ” (compare also the small southern Chinese people of the Mosuo ). In fact, Khasi husbands often do not bring all of their work into the wife's household or leave their partner (temporarily); this is balanced out by the unmarried male members of the extended family living with them and by the support of the wife's mother (grandmother of the children).

After a birth, a Khasi mother in her extended family is not only supported by her mother and other experienced relatives, but also by her social father (uncle), her favorite brother, and - if desired (and known) - the child's biological father .

Succession of the youngest daughter (ultimagenitur)

To this day, almost all Khasi cling to their traditional way of life within a matri- linear and matri- local social order (technical language matrifocality : "matricentriert, matrifocusiert"), in which the maternal lineage, choice of residence and succession predominates: the children are assigned to the mother and Goods, rights, privileges and duties are inherited from mothers to their daughters, preferably the youngest. The male descendants within an extended family also receive the family and clan name, are assigned to the entire lineage and live at their mother's place (as long as unmarried), at an advanced age with a sister and her children. However, they cannot pass this membership on to their biological children, because they are descended from their mother, not from her (compare rules of descent on descent). Therefore men do not inherit goods from their mother; they would be taken from family property without offering any benefit to the extended family. In the Jaintia tribe, a man's (motherly) clan can even claim his private property as clan property. A Khasi man cannot bequeath anything to his children except personal things, because the inherited goods would change from his mother's clan to the clan of the mother of his children. Such a change of property and land between clans is impossible and only possible in mutual mutual exchange (in earlier times sometimes also warlike).

The land and buildings belong to the group mother, mostly managed by her brother or her social father (uncle). The income from work, agriculture, production and trade of the family members also goes to the mother. In earlier times, the Khasi had no distinct private property apart from their personal jewelry , land owned by a large family is still mostly managed in the form of a cooperative or cooperative (see above on the large family as social insurance ).

Ultimagenitur

The youngest daughter of a Khasi mother has an official title: ka Khadduh (“the custodian” of the ancestral property), bestowed by the mother when she does not want another child. According to tradition, the last-born is the mother's chief heir and will inherit the family's house and land (compare heir daughter ). She will cherish her mother's jewelry, which may have been accumulated for generations. Older sisters expect a small share of the inheritance, especially when they are about to start their own “house” ( iing ) . Sons rarely get an inheritance share, maybe some movable property like animals, but no land. In the case of the War-Khasi tribe (in the southern border area) the inheritance is divided equally between daughters and sons.

The succession to the youngest child is technically called Ultimogenitur (lastborn right), in the case of the youngest daughter Ultim a genitur (“the lastborn as succession”) - in double contrast to Primogenitur as the right of inheritance of the firstborn son in patrilineal families. In some Khasi areas, the youngest daughter receives the best school education right from the start; Schooling is generally encouraged, but women have 3% more reading skills than men (see above on the literacy rate ). In contrast to the Khasi, among the matrilineal people neighboring to the west, the Garo prefers to inherit the eldest daughter (the firstborn as heir daughter: Prim a genitur). With them the position of the village director (nokmas) is only taken over by a youngest daughter.

The following diagram shows the succession of the youngest daughter:

| " Mother " | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sons |

youngest = heir |

older daughter |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Grandsons |

(youngest) granddaughter |

(youngest) granddaughter |

Grandsons | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After the death of the “mother”, her youngest daughter inherits most or all of the economic assets and family land and becomes the new head of the extended family ( iing ) or the larger lineage ( kpoh ) . She could very well be a grandmother herself. She also inherits the ka bat ka Niam , the religious, spiritual responsibility for the extended family (see below on the religion of Niam Khasi ), as well as the ka ling-seng , the group ceremony (iing: house, family; seng: united). The understanding of the united Khasi extended family as a managed cooperative requires constant coordination with all adult family members, including the more experienced and respected elders, from the heiress . She will in turn pass on the management and the entire property to her youngest daughter; In this form, the Lineages have held their country together for many centuries, but have always supported the newly emerging family branches with a house and a small field. The youngest daughter of an “older daughter” also inherits their property and jewelry, if they have already been accumulated; in any event, she inherits responsibility for her siblings and her sisters' children (her nieces and nephews).