Opiza

Opiza ( Georgian ოპიზა ) is the ruin of the oldest monastery of the medieval Georgian kingdom of Tao-Klardschetien in what is now the northeastern Turkish province of Artvin . It was founded around 750 AD and lasted until the beginning of Ottoman rule in the 16th century. Here was the cultural center from which the monk Grigol Chandsteli began to revive the Georgian Orthodox monasteries in Tao-Klardschetien at the beginning of the 9th century after the retreat of the Muslim Abbasids . The few remaining remains in today's village of Bağcılar can hardly be assigned to the former St. John's Church, which received its last form at the beginning of the 10th century, and the monastery outbuildings.

location

Coordinates: 41 ° 13 ′ 25 ″ N , 42 ° 2 ′ 7 ″ E

From Hopa on the eastern Black Sea coast , expressway 10 leads in a south-easterly direction in the Çoruh valley inland. About ten kilometers after Artvin , the road leaves the Çoruh, turns northeast and follows the Berta Suyu (Georgian Imerchewi ), a tributary of the Çoruh, to Şavşat in an increasingly narrow and steeper gorge. The ruins of the churches of four Georgian monasteries have been preserved along this route on the right (northern) bank of the river. The first branch leads to Dolisqana in Hamamlıköy village. A narrow dirt road branches off about 20 kilometers to the east, which initially runs parallel to the expressway on the slope and only gradually increases in height. After five kilometers a fork in the road is reached, from which it is now two kilometers in serpentines uphill to Opiza. From this fork, the path runs straight ahead at approximately the same height on the rocky slope above the valley floor for another seven kilometers to the ruins of Porta, which is identified with the Chandsta monastery . The Tbeti Cathedral just before Şavşat ends the series. About 30 kilometers south of the Berta-Suyu, in the side valley of the Ardanuç Çay (Georgian Artanudschistskali ), the ruins of Yeni Rabat have been preserved near the small town of Ardanuç . The former Schatberdi monastery was probably located here.

The place Bağcılar consists of a few farms scattered far on the slope of the Imerchewi Mountains (Turkish Imerhevi Deresi ). The rugged rocky mountains represent the southern drop of the Karçal Mountains ( Karçal Dağları ), the highest peak of which reaches a height of 3415 meters just under 20 kilometers to the northwest. The remains of the monastery cannot be seen from the path. On the outside of a sharp left curve is a small mosque from 1964 ( Bağcılar Köy Camii ) with benches and a washing area in front of it. The one-room school attached behind it was no longer in operation at the end of 2012. The school building is adjacent to the monastery ruins.

history

The first Georgian monasteries were founded in the Kartlien region in the late 5th or early 6th centuries . When south-western Georgia, which today belongs to Turkey, was practically depopulated after the campaigns between Georgians and Arabs at the end of the 8th century, the inaccessible, steep and rocky side valleys in northern Tao-Klardschetien provided suitable places for the monks to found Here, far from the Arab emirate of Tbilisi in eastern Georgia, a new monastic life emerged, which produced an independent cultural tradition. In the 9th and 10th centuries, numerous churches and monasteries were built in Tao-Klardschetien. At the end of the 10th century, the Bagratiden king Bagrat III. Tao-Klardschetien with three other principalities to the Kingdom of Georgia .

One source on Georgian history is the collection "The Life of Georgia" ( Kartlis chovreba ), in which writings from the end of the 10th to the middle of the 13th century, the "Golden Age" of Georgia are summarized. This corpus informs that the Iberian King Vakhtang I. Gorgassali (r. 452–502) instructed his stepbrother Artawaz, the prince of Artanuji , to build a fortress in Artanuji, a monastery in Opiza and churches in three other places. Obviously, however, the name Opiza was added later, which is why a first monastery foundation in the second half of the 5th century cannot be proven.

According to more reliable sources, Opiza was the oldest monastery in Tao-Klardschetien and was founded in the middle of the 8th century. The monk Grigol Chandsteli (759-861), about the Giorgi Mertschule from the Chandsta monastery in his 951 hagiography "The Life of Grigol Chandsteli" reported, came to Tao-Klardschetien around 794. He is said to have lived initially in Opiza and from here at the suggestion of King Ashot I (r. 813-830) founded three monasteries and two nunneries in the 830s and 840s. This can also be found in another publication entitled “The Life of Serapion of Sarsma ” about the monk Serapion , who died around 900 . Medieval scribes referred to the miraculous power of John the Baptist, which Grigol is said to have inspired in his work. Other monasteries were founded by Grigol's pupils in the following decades. It is thanks to all of them that the valley of Berta Suyu became the center of the "Georgian Sinai ". Monks from Opiza are said to have helped build the Chandsta monastery. That was at a time when there was no other monastery in the area. At another point in “The Life of Serapion of Sarsma” it is mentioned that when Grigol arrived with Amba Giorgi, the third abbot presided over the monastery. From this a foundation by the abbot Samuel can be calculated around the middle of the 8th century. The stonemasons involved in the construction were named after this source Amona, Andrea, Petre and Makari.

Aschot's son Guaram Mampali († 882) restored or expanded the Opiza monastery and was buried there , according to another chronicler gathered in Kartlis chovreba . The construction work must have taken place shortly before his death. The monastery church was rebuilt on an even larger scale shortly before the middle of the 10th century. According to inscriptions, the refectory (dining room) was built in this third construction phase and the previous basilica was converted into a cross-domed church. Interpreted to confirm the dating Djobadze in the inscription, which is below a poorly preserved rulers painting on the wall of Südarms was ( "Ashot kouropalates , the second builder of Opiza and this holy church"), the name of the king as Ashot II. ( reg. 941-954). He was the only one among the numerous namesakes who, next to Aschot I, bore the title of Kuropalates. Other historians read the ruler as Aschot I and thus started the conversion to a cross-domed church a good 100 years earlier.

In the scriptoria of many monasteries, monks copied illuminated manuscripts that are of great importance for historical research. The Opiza monastery became a well-known religious center thanks to its training center. Among other things, the monks copied the “Tetra Evangelium of Opiza” dated 913 , which is now kept on the Greek peninsula of Athos . In addition, the Schatberdi collection of writings stands out from the year 973 because it enables the new building of the Barhal monastery church (in Georgian Parchali ) to be dated, which must have taken place a few years earlier. In Tbilisi there is a Parakliton ( liturgical text which may contain hymns and musical notations).

Goldsmiths were also employed in the monastery, who made the implements required for worship such as beakers, communion chalices , host bowls and crosses. Remained a from King David III. (Kuropalates, reg. 961–1000) commissioned processional cross made by a goldsmith named Asat, high-quality metalwork by Besken and Beka, which both worked in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, as well as artistically designed book covers from this period.

When it was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, the monastery was abandoned and the buildings were left to their own devices. The nobleman and general in the service of the Russian army Giorgi Kazbegi (1840-1921) came in 1874 as part of a reconnaissance mission in the Georgian areas under Ottoman rule. In his travel notes, he first described the churches there. We owe a description from 1879 to the Georgian historian and archaeologist Dimitri Bakradze (1826–1890). In 1888 the Russian architect Andreĭ Mikhailovich Pavlinov (1852–1898) visited the place and in 1904 the linguist Nikolai Jakowlewitsch Marr came . All stayed for only a few hours or a day, but in the short time they managed to copy some Georgian inscriptions . A photo from 1903 shows the church with the dome completely intact. Nicole and Jean-Michel Thierry were the first art historians who were allowed to undertake research trips to the previously inaccessible northeast of Turkey after the Second World War. In photos that they took in 1959, the church can be seen with the drum but the collapsed folding roof. The Georgian art historian Wachtang Djobadze visited the church in 1965 and found only thickly overgrown ruins, which he cleared from the bushes. In 1990 the visit “only for experts” was worthwhile.

architecture

Following the example of traditional residential buildings ( darbasi ), central buildings were built in Georgia from the middle of the 6th century , which later reached a monumental size. Its layout in the form of a Greek cross formed the basis of the Georgian church building. The dome above the central church space is raised by a windowed drum and the west nave is often lengthened by combining it with the basilica-style floor plan . The predecessor buildings of the cruciform monastery churches preserved as ruins in Tao-Klardschetien were single-aisled hall churches or three aisled basilicas built at the end of the 8th or beginning of the 9th century .

The remains that exist today in Opiza along a road branching off to the east no longer allow an idea of the original building structures. In addition to a long wall along the way, there are some fragments of the wall on the hill above. The description is based on what was available until the middle of the 20th century. The cross- domed church had an unusually long west arm , which protruded from the central domed room in the same width as the east apse . The total length of the church was 27.25 meters inside, between the south and north cross arm it was 11.5 meters inside. The barrel vault of the nave was divided into five segments by four belt arches that rested on pilasters along the long walls . The apse was semicircular inside and lay within the straight east wall. It was flanked by two rectangular adjoining rooms ( pastophoria ) measuring 2.5 × 1.9 meters , which had access to the nave but no direct connection to the apse. Basically, the basic plan corresponds to that of the neighboring monasteries Dolisqana and Chandsta (Porta), with the difference that there the cross shape is hidden in an outer rectangle. In Opiza and Haho, however, the northern and southern cross arms protrude beyond the rectangular base.

The dome towered over a drum that was round on the inside and twelve-sided on the outside. Four zygomatic arches arranged in a square carried the tambour and transferred their load to the inner wall corners. As in Yeni Rabat, pseudotromps represent the transition between the square and the circular shape of the drum, i.e. gussets composed of pendentives and trumpets . Of the twelve wall fields on the outside of the drum, bordered by double columns and round arches, six were pierced by window openings. Corinthian capitals with stylized acanthus tendrils crowned the pillars. The same structure was adopted in a simpler way for the inner wall of the drum: Flat arches and simple half-columns surrounded the twelve fields. A folded roof rose above the dome in the zigzag shape of a half-open umbrella.

The walls were made of uniformly large sandstone blocks with roughly hewn surfaces in almost flat layers. In contrast, the vault of the main nave consisted of blocks neatly joined and smoothed with a thin layer of mortar. According to Marr's description, the vaults of the two aisles, as well as the upper round apse and the dome, were partly made of bricks. The use of bricks was widespread in the 10th century, and some barrel vaults were also made of bricks in neighboring Dolisqana. On the inner west walls of the two cross arms there were niches 2 meters high and 0.9 meters wide, the purpose of which is unclear, but which appear similarly in the monastery churches of Öşk Vank , Haho and Barhal .

The second largest building with 20.8 × 15 meters was the refectory, which was added during the expansion phase in the 940s. It stood as a three-aisled, rectangular hall in the southwest of the church. The barrel vaults, divided by girders, were supported by a double row with three pillars each and corresponding wall brackets. The size of the dining room suggests a large monastic community.

Building sculpture and painting

In Opiza, pseudotromps and other architectural decorations were introduced into the region, which, along with structural improvements, were subsequently used in other churches. However, some of the innovations tried out in the church in Chandsta, which was built between 918 and 941, were adopted during the later renovation phase in Opiza.

The window reveals on the drum were painted with geometric patterns such as rhombuses and spirals, the blind niches there were filled with prophets in long robes who held scrolls in their hands.

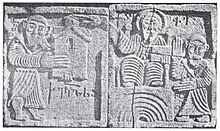

The only figurative relief was once attached to the south facade, today it is in the National Museum in Tbilisi . The left figure on the sandstone shows, according to the old Georgian inscription ( mrgvlovani ), King Ashot in bas-relief, as he, with the model of a cruciform church in his hands, humbly moves to the right, where Christ awaits him. Aschot can be seen in a strict frontal view, he is wearing a festive coat with a raised collar and a belt that is decorated with metal plates and hanging cords. On the second relief stone, Christ sits on the throne in heaven as the ruler of the world. According to 1 Kings 10, 18–20, this throne stands in the seventh heaven, above the lower six heavenly spheres, which are indicated here as semicircles. Christ holds an open book in his left hand, and extends his raised right hand over the model of the church in a blessing. To the left of Christ is a David, also marked by an inscription, who is dressed like Ashot. The figures are schematic, linear and dispense with harmonious human proportions. According to a tradition that emerged in the 9th century, a ruler depicted in this way is usually the most famous of the Georgian kings, Ashot I († around 830), who, according to legend, relates his origin to the biblical prophet David . In order to reinforce this historical myth , which is essential for the Georgian people , the two were often depicted together. In this case, however, it seems more likely that it is Aschot II (r. 941-954) and his brother David II. (R. 923-937). For the prophet, this David would have been a little too small compared to Ashot and the clothes would not have been appropriate. A very clear indication of this ascription is the church model, because it shows the cross-domed church after the renovation and not the previous basilica.

literature

- Wachtang Djobadze: Early Medieval Georgian Monasteries in Historic Tao, Klardjetʿi and Šavšetʿi. (Research on art history and Christian archeology, XVII) Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1992, pp. 9–18

- Volker Eid : East Turkey. Peoples and cultures between Taurus and Ararat . DuMont, Cologne 1990, p. 201, ISBN 3-7701-1455-8

- Thomas Alexander Sinclair: Eastern Turkey: An Architectural and Archaeological Survey. Vol. II. The Pindar Press, London 1989, pp. 21f

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hacik Rafi Gazer : Georgian Orthodox Church. In: Bernd Schröder (Ed.): Georgia - Society and religion on the threshold of Europe. Röhrig Universitätsverlag, St. Ingbert 2005, p. 60

- ↑ Djobadze, p. 15f

- ↑ Sinclair, Jan.

- ↑ Heinz Fähnrich : Grammar of the old Georgian language. Buske, Hamburg 1994, p. 7, ISBN 978-3875480658

- ↑ Tbilisi, Institute of Georgian Manuscripts

- ^ Georgia. ( Memento from January 25, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) International Research Center For Traditional Polyphony Of Tbilisi State Conservatory

- ↑ Djobadze, p. 17f

- ^ Bruno Baumgartner: Unknown and less known Georgian monuments in northeast Turkey. ( Memento of February 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (PDF; 8.5 MB) In: Vakhtang Beridze (Ed.): 1st International Symposium of Georgian Culture. 21.-29. June 2008, p. 183

- ↑ Djobadze, p.9

- ^ Oath, p. 201

- ^ Edith Neubauer: Old Georgian architecture. Rock towns. Churches. Cave monasteries. Anton Schroll, Vienna / Munich 1976, p. 32f

- ↑ Djobadze, p. 14f