Paper Print Collection

The Paper Print Collection ( German : collection of paper prints ) is a collection of contact prints of historic American movies on Bromidpapier mainly 1894-1912 for registration of copyright in the United States Copyright Office of the Library of Congress have been filed. Since more than 90 percent of the film production from this period are considered lost films , the paper prints obtained are of great film historical importance as film heritage . In individual cases, until 1940Paper prints submitted. Kemp R. Niver , who received an honorary Oscar for this in 1955 , developed special processes and devices for restoring paper prints on film material.

By 1967, Kemp Niver had copied all approximately 3000 completely preserved films onto 16 mm film , although there were significant quality losses. The restoration of the complete paper prints on 35 mm film and their digitization continue to this day. In addition, the collection also includes a sub-area of prints that represent only a fraction of films. This Paper Print Fragment Collection contains material from those films whose copyright has only been registered by submitting contact sheets of individual or a few individual images to short sequences of consecutive images. Although these fragments do not allow the restoration of entire films, they are nevertheless of great film historical value.

Paper Prints in the United States Copyright Office

First paper prints

1891 began with the development of Kinetographen and the Kinetoscope by the American inventor Thomas Alva Edison and his assistant William KL Dickson , the film history of the United States . The Copyright Law required at the time an application to be protected works and could not be applied easily to the new medium of film. In order to be able to claim copyright protection for films, a contact print of the film images had to be submitted on paper between 1894 and 1912.

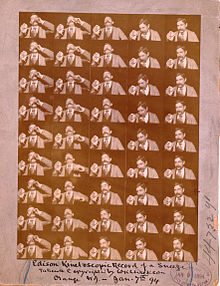

The first paper prints were submitted for registration in August 1893 by an employee of Edison Studios , presumably William KL Dickson. For these and all other paper prints , each of which contained numerous individual images, the registration was carried out as a single photograph - with a simple registration fee. The first paper prints are lost. As the oldest still existing paper print , Fred Ott's Sneeze was registered on January 9, 1894 under the title Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze, January 7, 1894 . In the following two decades, several thousand films were registered in this way.

Many of the films contained in the Paper Print Collection are the products of fraudulent machinations. So the film was The Great Train Robbery (The Great Train Robbery) of the American director Edwin S. Porter in 1903 with a Paperprint logged. In the following year, Siegmund Lubin registered a film with almost the same title (Great Train Robbery) , which is either an illegal copy of Porter's film or a detailed re-enactment of the film made scene by scene. Other films could be identified as works by Georges Méliès believed to be lost .

Full movies

In the years from 1894 to 1912, in most cases, complete films were copied onto strips of paper and submitted rolled up. However, there was no fixed limit, so in 1914 the American Film Manufacturing Company registered the copyright for two films by Lorimer Johnston , the film adaptations of the story Das Heimchen am Herd by Charles Dickens and A Child of the Desert , with the complete film being presented as a paper Print on.

The Paper Print Collection encompasses the entire spectrum of film production, both fictional works and documentaries of historical events and interesting incidents of all kinds. This includes images - partly in reenactments - of the Spanish-American War , the Russo-Japanese War , the execution of William McKinley assassin Leon Czolgosz on the electric chair and killing the elephant Topsy by electric current, from the damage of the Galveston hurricane and early commercials and pictures from world fairs. However, the collection is not a complete record of films made in the United States from 1894 to 1912 or any other period. Individual film studios waived the copyright. Others, like Edison Studios or the American Film Company , protected almost all productions.

The collection contains more than 3,000 complete films with a cumulative film length of more than 3,000,000 feet of paper on rolls. This corresponds to a demonstration duration of more than 300 hours. In addition, there is the Paper Print Fragment Collection with tens of thousands of individual images or short strips with which the copyrights of a further 2,474 films have been registered.

- Films reconstructed from the Paper Print Collection

Cattle in the Union Stock Yards , 1897

Advert for cigarettes, 1897

Replicated execution of the presidential murderer Leon Czolgosz , 1901

Killing the elephant Topsy , 1903

Re-enactment of the Battle of Chemulpo , 1904

Paper Print Fragment Collection

The Paper Print Collection has become known among film historians and those interested in film history because of its large inventory of 35 mm films completely copied onto paper rolls. In addition to these paper prints in the narrower sense, the collection also includes a part that was only perceived late by research as the paper print fragment collection . Most of them are single images or short strips of contact prints made after 1912, whereby the English term fragment does not refer to an isolated fraction of an originally complete film, but refers to the method of submitting short film sequences to the Copyright Office. Since the Copyright Law did not contain any provisions for films, the film studios managed to submit a large number of different materials, in addition to complete films on paper, films on celluloid, individual images in film format as copies on paper or celluloid, still images or enlarged individual images and flip books . Such single images or short sequences do not allow reconstruction of the whole movie and many American films are therefore despite logging copyright -lost films . Others, such as The Star of Bethlehem , have only partially survived.

The materials submitted for the application of copyright not only differed from studio to studio, but also changed over time within a studio. From October 1896, Edison Studios registered the copyright for almost all of their films. From October 1896 to August 1897 they submitted strips of celluloid film for each individual scene. Subsequently, until 1905, complete films were submitted as paper prints on rolls, then until 1911 only individual images and later no image material at all.

The registrations of the copyright were recorded chronologically by handwritten entries in the copyright record books, whereby the submitted documents were also indicated. This means that the extent of the consignments can still be traced today. The paper print fragments , however, have not survived as densely as the complete paper prints of earlier decades. After 1912, the studios submitted large numbers of complete copies on 35 mm celluloid film, which were stored together with the Paper Print Fragments . The chemical decomposition of the celluloid films therefore also affected numerous paper print fragments , which were irretrievably destroyed.

Townsend Amendment of 1912

With effect from August 24, 1912, the Copyright Law was extended to include films by the Motion Picture Amendment or Townsend Amendment . This opened up additional options for obtaining copyright protection for an entire film, such as storing scripts or individual images. Notwithstanding this, a few paper prints were still submitted until 1939 .

The filing of paper prints continued even after the copyright change in 1912, as the Library of Congress wanted to avoid the legally possible storage of the flammable celluloid film . There are all conceivable gradations between the minimum requirement of a single image of each scene and the delivery of complete films as paper print or on cellulose film. Occasionally, paper prints were submitted until the 1940s , only then did the Library of Congress have suitable storage rooms for celluloid film.

Alleged loss and "rediscovery"

In connection with the Paper Print Collection , the legend is spread that the collection was lost for decades. This description is not entirely true. In fact, there were likely at all times the Library of Congress staff who knew about the Paper Print Collection and its location. But they did not attach any importance to the collection. In particular, they were not aware that it contained several thousand mostly lost films. The files of the Library of Congress have an approximately 1937 or 1938 newspaper article entitled Early Movies Red In Cellar, Priceless Records of a Great Industry Filed Away in Dusty Obscurity down (German, mutatis mutandis: Early films rot in the basement Priceless certificates. of a great industry are forgotten in the dust ). However, this article has not yet been found.

When Archibald MacLeish was appointed head of the Library of Congress in 1939, he immediately began to tackle the unfinished business of his predecessors. He carried out a major restructuring of the Library of Congress, with which the previously 35 administrative units were combined into five departments. One of them was the Copyright Office. There one began with the creation of catalogs of the registrations, with the directory of the films was concerned among other Howard Walls . Walls was very interested in the paper prints and eventually got permission to catalog this collection in his spare time.

In the summer of 1942, Walls first had access to the storage room, a basement room in the main building of the Library of Congress. He later recalled that the lock could no longer be opened and had to be sawed open and that the room was filled to the ceiling with countless rolls of paper prints . The film critic Theodore Huff disagreed with Walls' version of the sole discovery of the "lost" material . Huff was an employee of the Museum of Modern Art Department of Film in the 1930s , but was fired by curator Iris Barry after persistent disputes with colleague Jan Leyda . Since 1941 he lived in Washington, DC and had a great interest in being involved in the processing of the inventory of paper prints . In letters to friends and acquaintances in 1942 and 1943, he presented himself as the real discoverer of the collection and claimed to have brought the National Archives and Records Administration and its optical printer into play. Huff's account finds no echo in Library of Congress publications that do not even mention him. In the spring of 1943, the contact between Walls and Huff seems to have completely broken off, but even years later, in private and professional circles, Huff made derogatory comments on Iris Barry and Howard Walls, and at the end of 1947 tried one last time with regard to Paper Print Collection to bring to business. Since Huff's correspondence shows detailed knowledge of the collection, his early involvement cannot be denied. The justification for the claims of Walls and Huff, who each give themselves priority in the discovery and development of the restoration process, is unclear.

The first catalogs of copyright entries for films appeared in 1951 (films registered from 1912 to 1939) and 1953 (films from 1894 to 1912). The volume with the registrations from 1894 to 1912 is the only one with the name of an employee responsible for the compilation, Howard Lamarr Walls.

Restoration of the paper prints

The Paper Prints were after decades of storage in a generally excellent condition. Most of the films, with the exception of a few outer layers, were protected by being rolled up so that air and moisture did not destroy the sensitive emulsion layer. However, the bromide paper had become brittle and severe wrinkling occurred when it was spread flat. The film restorer Kemp R. Niver compared the state of the image-bearing emulsion layer on the paper strips after decades of storage in a rolled-up state with the deep wrinkles on the inner surface of a relaxed hand. As the hand muscles are stretched, the strong wrinkles disappear. When the rolled-up film is spread flat, the emulsion layer of which is on the outside, the rolled-up, smooth image is distorted by the strong folds. The paper prints first had to be soaked in liquid and then dried again when laid flat. As a result, the substrate, which had become brittle, regained its elasticity, the image acquired a matt gloss and the quality of the image was also greatly improved.

The restoration of the films in the Paper Print Collection - in the sense of restoring complete films on motion picture film in various formats or in digitized form - began in the early 1940s and has not yet been completed. At least six phases of restoration can be distinguished, some of which overlapped, which comprised a differently large part of the collection, and whose processes were repeatedly surpassed and replaced by new technologies.

Howard Walls and Carl Gregory (1943–1945)

In early 1943, Howard Walls contacted Carl Gregory . It turned out that Gregory was already familiar with paper prints . In his youth he had worked for Edison Studios and his duties included making paper prints . Gregory was confident that retransferring to film would be possible. For this purpose he modified an optical printer used in the National Archives and Records Administration and developed by himself , which was originally intended for processing brittle and crumpled roll film. The results of the first tests presented Gregory and Walls on March 5, 1943 in New York City at a conference of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers. The following day, the New York Times reported on the restoration project, quoting Walls as having 5,000 films to be edited between 1897 and 1917.

In March 1944, the journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers published two articles by Howard Walls and Carl Gregory in which they gave details of the Paper Print Collection and the restoration process. In contrast to film material, it was not possible to shine through the image strip. The carrier material is opaque and must be illuminated and photographed from the image side. Gregory and later also Dunn countered the problem of the different transport holes with a self-developed transport system that allowed the processing of all 35 mm films . Different image formats of the original were countered with setting options on the optical printer, which could expose 35 mm roll film with and without soundtrack.

Richard Fleischer and Linwood Dunn (1943–1949)

At the time, RKO - Pathé had the very successful series Flicker Flashbacks in its program, in which historical silent films were accompanied by music and spoken text, mostly with comical content. The series was directed by Richard Fleischer , who had read the article in the New York Times and saw an opportunity to tap films for his series. Fleischer offered the Library of Congress for the granting of the performing rights to copy paper prints onto film and to give the library a copy.

The Library of Congress and Richard Fleischer agreed on the following procedure: Fleischer informed Howard Walls of the subject he wanted footage on. Walls made a list from which Fleischer could choose the titles he was interested in. He then sent an order to the National Archives and Records Administration and the Library of Congress, which in turn billed him for the effort. RKO-Pathé provided the unexposed roll film for the copies. This restoration phase lasted until around 1945, when NARA needed its technical equipment for its own tasks. Fleischer found an alternative solution as early as 1943, the paper prints were now sent to RKO-Pathé, where Fleischer's employee Linwood G. Dunn took care of copying with an optical printer he had developed himself. The restorations in cooperation with RKO-Pathé continued at least sporadically until the spring of 1949, then the flicker flashbacks were discontinued.

Howard Walls and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (1947–1953)

In the spring of 1945, Luther H. Evans , the new head of the Library of Congress, began to drastically upgrade the film department. When he asked Congress to expand the film department's staffing plan from 17 to 72 positions for the 1947/48 budget year, almost all funds were cut; In particular, there was no longer any money available for film restoration. In this situation, Howard Walls approached the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences with Evans' permission . Their managing director Margaret Herrick was quickly enthusiastic about Walls project and organized a dinner with Walls, herself and the board members Walter Wanger , Jean Hersholt , Donald Nelson , Sam Brown, Mary McCarthy and Michael Romanoff in Romanoff's Restaurant. Walls was offered the position of curator of the Academy's film collection, his main role being to oversee the joint venture with the Library of Congress. On October 15, 1947, a brief note appeared in Variety magazine reporting the plans. The fact that Walls was called the discoverer of the films and allegedly claimed to be the developer of the restoration process prompted Theodore Huff to intervene again. On November 11, 1947, he wrote a letter to Jean Hersholt, in which he denied the role of the "publicity-addicted opportunist" Walls. Notwithstanding this dispute, which ended the following year with Huff's legal defeat, the Academy signed the contracts with the Library of Congress on December 2, 1947.

In February 1948, the first 69 paper prints were sent to the Academy. As early as early summer, it became known that Walls was having difficulties obtaining the funds for the restoration project. In January 1950, the Library of Congress requested from Walls a report on the progress of the work. She was put off by Walls, referring to his efforts to finance and solve technical problems, and granted an extension of the loan period of six months. In July 1950, Walls wrote to the Library of Congress that he may with the Ford Foundation could cooperate in raising funds and that he was confident of 300,000 US dollars to obtain. The Library of Congress repeatedly asked for results and was concerned that Walls wanted more film to edit but was not returning copies of edited films. A start-up financing of 75,000 US dollars, which Walter Wanger had already promised in 1947, never arrived, and Margaret Herrick was also becoming increasingly impatient. In January 1951, sent Walls two edited movies at the Library of Congress, the frame by frame manually copied The Doctor's Bride of Lubin Manufacturing Company from 1909 and machine-copied Hash House mashers of Keystone Studios was from 1915. As expected, the hand copied film of significantly better quality. The poor results no longer helped Walls, he was pressured from all sides and rumors arose that some of the films he had been given had disappeared.

In 1952, the Academy hired the former police officer and private detective Kemp Niver , who had previously worked on their behalf, to recover the paper prints that Walls had sent to several locations and no longer verifiable . Niver succeeded quickly and was able to find the missing paper prints . Herrick gave Walls the choice of resigning himself or being fired. The then resigned Walls, however, was reinstated by the Academy in May 1953 with significantly reduced competencies and at a significantly lower salary in order to maintain the existing contact with the Library of Congress.

In the meantime, Kemp Niver had let the Academy know that he knew a little about photography and film technology. He had already traveled to Washington, DC with some of the recovered paper prints and had tried unsuccessfully to have them copied by various film laboratories. As a result, he developed and built a device for copying the paper prints . He was able to convince the Academy of a test that turned out to be everyone's satisfaction. Howard Walls resigned again on August 31, 1953 and Margaret Herrick announced that Kemp Niver could now take over the project.

Kemp R. Niver (1953 to 1967)

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offered the Library of Congress the opportunity to copy paper prints onto 16mm motion picture film at a cost of 32 cents per foot. The Library of Congress accepted the offer and the Academy signed a contract to this effect with Primrose Productions, founded by Kemp Niver for this purpose (from 1954: Renovare Film Company). The first twelve restored films were shown on November 30, 1953 by the Academy and the Library of Congress as part of a press screening. Large-scale restoration of the films began in early 1954. The Library of Congress Paper-Print Conversion Program was started by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and funded for two years. The United States Congress followed a bill by California Senator Thomas H. Kuchel and in 1958 provided additional funds with which the project could continue until 1964.

In 1953, cameras were used to photograph the paper prints , which were taken picture by picture individually and by hand. The decision to copy the mostly wider paper prints onto 16mm film was probably made out of the consideration that they would be shown on television. Copying onto narrower film was associated with a loss of quality, which was also evident at the time, but this was of no significance given the image quality on television, which was even worse at the time. In addition to the loss of quality due to the transfer to narrower film, the copies made by Kemp often do not correspond to the original because individual images that the operating staff perceived as defective were left out during the copying process.

By 1964, the restorers' equipment had been significantly improved. The copier systems used at that time were able to take 16,000 pictures in six hours. By 1967, all 3,000 paper prints had been transferred to 16mm film by Niver's company . The optical printer used by Kemp Niver was handed over to the Department of Photography and Cinema at Ohio State University in 1967, where it continued to be used for the restoration of historical films, namely for copying from celluloid film to security film .

University of California (from 1985)

In the mid-1980s, Kemp Nivers former assistant William Ault and others at the University of California at Los Angeles copied paper prints onto 35mm film. To do this, one of the optical printers that Niver had used was converted to 35 mm film. Since the results were unsatisfactory, an optical printer with computer control was soon used, which allowed the individual images to be adjusted electronically.

National Digital Library Program (from 1995)

Beginning in 1995, the Library of Congress also copied films from the Paper Print Collection onto 35mm film. For the first time, the picture frames were adjusted by computer to reduce flickering. Both the wider film format and the computer control of the manufacturing process produced copies of unprecedented quality. These copies were digitized and made available online as part of the National Digital Library Program .

In contrast to Niver's work from the 1960s, since the 1990s restoration work has been carried out strictly to ensure that it is faithful to the original. Individual images and entire sequences that were incorrectly exposed or damaged during storage are also copied.

M / B / RS Motion Picture Conservation Center of the Library of Congress (since around 2000)

The M / B / RS Motion Picture Conservation Center in Dayton , Ohio , part of the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress, began converting paper prints onto 35mm film in the late 20th century copy. These 35mm film copies formed the basis of a project that made 341 digitized films and 81 audio recordings from Edison Studios available on the Library of Congress website. Since opening in 2007, digitizing paper prints has been part of the job of the National Audio-Visual Conservation Center in Culpeper , Virginia . The aim is to digitize the entire Paper Print Collection, including the films that have only been preserved in fragments, and to make them available online.

Problems with the restoration

The restoration of the films encountered difficulties in individual cases, which at first seemed insurmountable and caused a considerable effort to solve the problem. In 1964 - ten years after the restoration work began - Kemp R. Niver named a number of 27 such problems, each of which could reappear on an unprocessed roll of paper. Of these, 13 had already been recognized in the first three weeks of the work, after two years 15 of these problems were known.

In the early decades of film production, there was no standard for the film format. Each film camera manufacturer followed what they thought was reasonable, and so the films were not compatible with each other. This also applied to the demonstration devices; Films from different producers each required their own projection technology. The differences concerned not only the width of the film or the dimensions of the individual images, but also the size, spacing and arrangement of the transport holes at the edges. Further aspects were that the photochemical properties of the films and the bromide paper for the production of the paper prints were subject to extreme fluctuations and that the individual working methods of the cameramen and the employees in the copy factories had a major influence on the appearance of film images and paper prints .

The short film Fred Ott's Sneeze , which was the first paper print to be registered and one of the first to be restored, presented several problems. No transport holes could be seen on the paper print , which are an important aid in synchronizing the image sequences, the print also had no recognizable dividing lines between the adjacent images and the image frequency was unknown. It was only during the restoration that it became clear that the film had been recorded with a much higher frame rate than the later usual 16 or 22 frames per second and that the paper print contained only a fraction of the frames of the complete film.

Unusual film formats were a common problem. For example, wide-angle lenses were unknown to the film pioneer Enoch J. Rector , for his film The Corbett-Fitzsimmons Fight he chose an unusually wide film format of 75 mm. The Mutoscope had similarly wide film , and the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company used a camera that exposed 68 mm film with no transport holes.

Another common problem was the diversity of the transport holes. The Edison Manufacturing Company had applied for patents on some of their developments , including the advancement of the film in cameras and projectors using a combination of transport holes in the film and a suitable transport mechanism. The patents were circumvented by numerous manufacturers of cameras and projectors by designing the transport holes differently from the Edison system. Because of the great variability of the transport holes at the edges of the films, the Renovare Corporation soon decided to dispense with transport holes as a control element in their processing.

From today's perspective, the restorations by Howard Walls, Richard Fleischer and Kemp Niver are no longer satisfactory. The Biograph Company films were shot on 68mm film and reduced to 16mm during restoration work in the 1940s to 1960s. This was associated with a considerable loss of quality, which later copies on 35 mm film were subject to to a lesser extent and which is largely avoided today with the option of digital processing.

Film historical significance

In many cases, the paper prints are the only survival of the films, as the early celluloid film was destroyed by chemical decomposition within a few decades. In addition, the film material was extremely flammable and not only triggered a large number of fire disasters in cinemas, but also caused the total loss of entire film archives. The Cinémathèque Française lost thousands of historically valuable films to fires in 1959 and 1980. A major cause of film loss has been the lack of interest in preserving them. Films were mass products and consumables. As soon as an economic benefit could no longer be derived from a production, its storage was expensive and dangerous. The material was occasionally used as a raw material for industry, for example a large part of the work of Georges Méliès in France . The registration of the copyright by depositing individual images of each film scene was the usual procedure in other countries. With the British Film Copyright Collection, there is an extensive collection of individual images from early British films, but these only prove the existence of a film and allow conclusions to be drawn about the title and producer. They do not allow the reconstruction of entire films.

The individual images and sequences of the Paper Print Fragment Collection can be used as reference material wherever film copies exist, but the sequence of the scenes does not correspond to the original version or where parts of a film have been lost. The value of the images received is increased by the registers of the Copyright Office, which often contain the intended sequence, image title or text annotations for the images.

The films in the Paper Print Collection made up the vast majority of the several hundred fictional films shown in 1978 in Brighton at the congress of the Fédération Internationale des Archives du Film (FIAF) . This event is considered a milestone in film history, because until then, film historians could only access films from the affected period from 1900 to 1906 from the memories of contemporary witnesses and incomplete archival material. Now they were able to work with the films themselves, which radically changed the image of the early silent film era.

The Paper Print Collection has been a cooperation partner of Dartmouth College in Hanover , New Hampshire since 2014 . There, the collection is being researched under various aspects as a pilot project within the framework of the media studies Media Ecology Project. The results have been published since 2015.

Use of the Paper Print Collection

American filmmakers such as Ken Jacobs , Hollis Frampton and Ernie Gehr have made extensive use of the restored films in the Paper Print Collection for their own film projects since the 1960s . In addition to the unique look into the history of the United States, the background is also the aspect of the public domain of almost all works. One example is Ken Jacobs' experimental film Star Spangled to Death , published in 2004, which was more than six hours long and consists almost exclusively of historical film documents and also includes a large number of films from the Paper Print Collection .

The American filmmaker and artist Bill Morrison , who also frequently uses historical footage in his films, shot his twelve-minute short film The Film of Her in 1996 . In it he uses the history of the Paper Print Collection as a framework for a fictional plot in which an archivist from the Library of Congress discovers and restores the collection. He is driven by his interest in a silent pornographic film , The Film of Her , which he saw as a boy. The connection between the unnamed protagonists of the film and Howard Walls and Kemp Niver is only created in the end credits.

The complete copying of the Paper Print Collection onto 16 mm film was completed in the mid-1960s. This meant that the films were basically available for screening. However, by 2017 only about 500 films from the inventory, that is less than 20 percent, had been digitized and made available online, although almost all of the material is in the public domain. For a long time, research into film history had to fall back on the copies in the Library of Congress and the interested public is largely excluded to this day.

literature

- Charles "Buckey" Grimm: A paper print pre-history . In: Émigré Filmmakers and Filmmaking , Special Edition of Film History 1999, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 204-216, JSTOR 3815323

- Carl Gregory : Resurrection of Early Motion Pictures . In: Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers 1944, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 159-169, digitized

- Patrick G. Loughney: A Descriptive Analysis of the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection and Related Copyright Materials . Ph.D. thesis, George Washington University, Washington, DC 1988

- Kemp R. Niver : From Film to Paper to Film. The Story of the Library of Congress Paper-Print Conversion . In: The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 1964, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 248-264, JSTOR 29781138

- Kemp R. Niver: Motion Pictures from the Library of Congress Paper Print Collection, 1894-1912 . University of California Press, Los Angeles 1967

- Kemp R. Niver: The First Twenty Years: A Segment of Film History . Artisan Press, Los Angeles 1968

- Kemp R. Niver: Early Motion Pictures. The Paper Print Collection in the Library of Congress . The Library of Congress, Washington, DC 1985 (catalog of all complete films)

- Claudy Op den Kamp: The Paper Print Collection: How Copyright Formalities and Historical Accidents Led to Film History . In: The University of Western Australia Law Review 2017, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp. 37–50, PDF (203 kB)

- Gabriel M. Paletz: Archives and Archivists Remade. The Paper Print Collection and "The Film of Her" . In: The Moving Image. The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists 2001, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 68-93, JSTOR 41167042

- Anthony Slide : Nitrate Won't Wait. A History of Film Preservation in the United States . McFarland 2013

- United States Copyright Office (Ed.): Catalog of Copyright Entries Cumulative Series. Motion Pictures 1912-1939 . Library of Congress, Washington, DC 1953, digitized

- United States Copyright Office (ed.): Motion Pictures 1894–1912. Identified from the Records of the United States Copyright Office by Howard Lamarr Walls . Library of Congress, Washington, DC 1953, digitized

- Howard L. Walls: Motion Picture Incunabula in the Library of Congress . In: Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers 1944, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 155-158, digitized

- Colin Williamson, Dana Driskel: Reclaiming "Lost" Films. The Paper Print Fragment Collection and the American Film Company . In: The Moving Image 2016, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 125-134, doi : 10.5749 / movingimage.16.1.0125

Web links

- Reclaiming American History From Paper Rolls by the Renovare Process . Film by Kemp Niver about the paper prints and their restoration, 1953 (18:32 minutes, English)

- Early Motion Pictures . Interview with Mike Mashon, Head of the Moving Image Section of the Library of Congress, about paper prints and early films (20 minutes, English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Kemp R. Niver : From Film to Paper to Film , pp. 248-250.

- ↑ a b c d e f Claudy Op den Kamp: The Paper Print Collection , pp. 39–41.

- ↑ Mike Mashon, Where It All Began: The Paper Print Collection , Library of Congress website , May 27, 2014, accessed February 6, 2019.

- ↑ a b Kemp R. Niver: From Film to Paper to Film , pp. 263-264.

- ^ Anthony Slide: Early American Cinema . Revised edition. Scarecrow Press 1994, ISBN 0-81082-722-0 , p. 17.

- ^ Scholar and Screen. Notes on the Motion Picture Collection of the Library of Congress . In: The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 1964, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 265-269, JSTOR 29781139 .

- ^ A b c Colin Williamson, Dana Driskel: Reclaiming “Lost” Films , pp. 126–129.

- ^ A b Early Motion Pictures Free of Copyright Restrictions in the Library of Congress , Library of Congress website, April 28, 2016, accessed February 6, 2019.

- ↑ Patrick G. Loughney: Thomas Jefferson's movie collection . In: Film History 2000, Vol. 12, No. 2, special issue Moving Image Archives: Past and Future , pp. 174–186, JSTOR 3815370 .

- ↑ a b c d e Kemp R. Niver: From Film to Paper to Film , pp. 250-253.

- ↑ Colin Williamson, Dana Driskel: Reclaiming “Lost” Films , pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Brett Abrams, Images of the Silent Era. The Library's Paper Print Fragment Collection . In: Library of Congress Information Bulletin 1997, Vol. 56, No. 16, accessed February 6, 2019.

- ^ A b Karen C. Lund: Inventing Entertainment: The Library of Congress Makes Edison Motion Pictures Available on the World Wide Web . In: Journal of Film Preservation No. 58/59, 1999, pp. 96-102, PDF, 1.14 MB .

- ↑ a b Kemp R. Niver: From Film to Paper to Film , pp. 259-260.

- ^ Charles "Buckey" Grimm: A paper print pre-history , pp. 204-205.

- ^ A b c Charles "Buckey" Grimm: A paper print pre-history , pp. 205-209.

- ^ A b Charles "Buckey" Grimm: A paper print pre-history , pp. 211-213.

- ^ A b c d Charles "Buckey" Grimm: A paper print pre-history , pp. 209–211.

- ^ Howard L. Walls: Motion Picture Incunabula in the Library of Congress

- ^ Carl Gregory : Resurrection of Early Motion Pictures .

- ^ Academy Mulls Plan to Preserve Old Pix . In: Variety , October 15, 1947, pp. 7 and 25, digitized .

- ^ Charles "Buckey" Grimm: A paper print pre-history , pp. 213-214.

- ^ A b c d e Charles "Buckey" Grimm: A paper print pre-history , pp. 214–215.

- ^ Charles Brackett : Project . In: Variety, January 6, 1954, p. 26, digitized .

- ↑ a b Kemp R. Niver: From Film to Paper to Film , pp. 258-259.

- ↑ Gabriel M. Paletz: Archives and Archivists Remade , p. 80 and footnote 18.

- ^ A b Andre Gaudreault, Jean-Marc Lamotte, Tim Barnard: Fragmentation and Segmentation in the Lumière "Animated Views" . In: The Moving Image 2003, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 110-131, here pp. 113-114, doi : 10.1353 / mov.2003.0004 .

- ^ Robert W. Wagner: Motion Picture Restoration . In: The American Archivist 1969, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 125-132, doi : 10.17723 / aarc.32.2.u773410561l5u6g0 .

- ↑ a b Gabriel M. Paletz: Archives and Archivists Remade , pp. 72–73.

- ^ Buckey Grimm: A Short History of the Paper Print Restoration at The Library of Congress , Association of Moving Image Archivists Newsletter 1997, No. 36, accessed February 6, 2019.

- ↑ Ken Weissman: The Library of Congress Unlocks The Ultimate Archive System , website CreativeCow.net, accessed February 6, 2019.

- ↑ a b Kemp R. Niver: From Film to Paper to Film , pp. 254-258.

- ↑ Paolo Cherchi Usai: Early Films in the Age of Content; or, “Cinema of Attractions” Pursued by Digital Means . In: André Gaudreault, Nicolas Dulac, Santiago Hidalgo (eds.): A Companion to Early Cinema , Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, MA and Oxford 2012, ISBN 978-1-4443-3231-5 , pp. 527-549, here Pp. 531-532 and pp. 538-539.

- ^ Regula Fuchs: Back to the future . Tagesanzeiger.ch, March 31, 2015, accessed on December 5, 2016.

- ^ State versus private - on the past and present of the Cinémathèque française: Cinema and Crisis . nzz.ch, June 30, 2003, accessed December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Liz-Anne Bawden, Wolfram Tichy (ed.): Rororo-Filmlexikon. Volume 5: People H – Q. Directors, actors, cinematographers, producers, authors (= Rororo. Pocket books 6232). Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Reinbek near Hamburg 1978, ISBN 3-499-16232-6 , Lemma "Méliès".

- ↑ Eileen Bowser: The Reconstitution of A Corner in Wheat . In: Cinema Journal 1976, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 42-52, doi : 10.2307 / 1224917 .

- ^ A b c Claudy Op den Kamp: The Paper Print Collection , pp. 43–45.

- ↑ Eileen Bowser : The Brighton project: An introduction . In: Quarterly Review of Film Studies 1979, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 509-538, here pp. 509-510, doi : 10.1080 / 10509207909361020 .

- ^ Mark Williams: The Media Ecology Project. Library of Congress Paper Print Pilot . In: The Moving Image. The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists 2016, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 148-151, doi : 10.5749 / movingimage.16.1.0148 .

- ↑ Gabriel M. Paletz: Archives and Archivists Remade , p. 70.