Galveston Hurricane (1900)

| Category 4 hurricane ( SSHWS ) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Migration path of the hurricane | ||

| Emergence | August 27, 1900 | |

| resolution | September 12, 1900 | |

|

Peak wind speed |

|

|

| Lowest air pressure | 936 mbar ( hPa ; 27.7 inHg ) | |

| dead | 6,000-12,000 | |

| Property damage | $ 20 million (1900) | |

|

Affected areas |

Puerto Rico , Dominican Republic , Haiti , Cuba , southern Florida , Mississippi , Louisiana , Texas (especially Galveston ), Midwest , Great Lakes Region , Atlantic Provinces of Canada | |

| Season overview: Atlantic hurricane season 1900 |

||

The Galveston Hurricane is the name given to the hurricane that destroyed the Texas city of Galveston on Saturday, September 8, 1900 . With average winds of over 200 kilometers per hour and gusts of up to 300 kilometers per hour, the Galveston hurricane was a category 4 storm on today's Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale .

The hurricane claimed a high death toll, some sources estimate 6,000 and others up to 12,000. Most official reports assume 8,000 fatalities. This makes the Galveston hurricane the third largest Atlantic storm, after the so-called Great Hurricane of 1780 and Hurricane Mitch in 1998. In the USA, the Galveston hurricane is one of the natural disasters alongside Hurricane Katrina in 2005 which claimed the most human lives and wreaked the greatest havoc.

Unlike today's hurricanes, the 1900 hurricane was not given an official name. But it is known under the name Galveston Hurricane of 1900 or Great Galveston Hurricane ( Great Galveston Hurricane in the English-speaking area). Older sources sometimes refer to the natural disaster as the Galveston Flood .

The city of Galveston

Geographical location

The special geographical location in the Gulf of Mexico of Galveston ( 29 ° 17 ′ N , 94 ° 50 ′ W ) contributed significantly to the catastrophe that took place on the Texan coast in September 1900 . The city is located on an elongated, narrow island off the coast, which also formed the southern border of Galveston Bay. The highest point on the island was in the middle of the city on Broadway in 1900 and was only 2.6 m above sea level . Most of the island areas, however, only rose a little more than 1.3 meters above sea level. If the sea level rose by 30 cm, as is usual with a normal high tide , the sea water washed over more than 300 meters of the width of the beach.

The island was connected to the mainland by road bridges and three railway bridges. However, the railway connection in the direction of Beaumont also used ferries onto which the trains and passengers were loaded.

The main Texan port

The city of Galveston was a prosperous city towards the end of the 19th century with a population of 38,000. There was a tram , three concert halls for art lovers, and the city already had electric light. 20 hotels of all categories had rooms available for visitors. In addition to local and international telephone traffic, there were two telegraph companies . From today's perspective, the number of inhabitants indicates a rather insignificant, medium-sized city. However, Galveston was the most important Texan trading center at the beginning of the 20th century and even outperformed Houston, 80 kilometers further north, in terms of economic power .

In the ranking of the US American ports , Galveston was in third place - in no other US American port was more cotton handled. Sixteen consulates had their headquarters in the city: Russia and Japan , among others, were represented. The city owes its economic supremacy on the one hand to the natural harbor of Galveston Bay, but to a certain extent also to the decline of the port city of Indianola, 200 km southwest on Matagorda Bay . 25 years earlier, Indianola had been a serious competitor for Galveston for economic supremacy in the region. The throughput in the port there was only slightly lower than that in the port of Galveston. In 1875, however, a hurricane destroyed Indianola to a large extent. The city was rebuilt after the first destruction. A second hurricane in 1886 caused similar damage. The city of Indianola was then abandoned by its residents. A second reconstruction was not carried out.

Storm hazard

A number of Galveston residents had concluded from the destruction and decline of Indianola that Galveston was also threatened by storm. The city of Indianola had been destroyed by the hurricane, although it was located in one of the protected sections of the Texan coast and a series of offshore islands should have mitigated the force of a storm coming from the direction of the Gulf. However, the storm drove a huge tidal wave through Indianola and transformed the prairie behind it up to thirty kilometers inland into an open water landscape. When the wind turned, these water masses flowed away again through Indianola at great speed and washed away the last remaining houses. In order to avoid a fate comparable to Indianola, a number of the Galveston residents demanded a protective wall that should protect Galveston from a comparable tidal wave. Their concern was not shared by the majority of Galveston residents.

The city of Galveston had weathered several strong storms without major damage since it was officially established in 1839. Many residents were therefore convinced that future storms would pass in Galveston without storm surges. An official meteorological report also contributed to the reassurance of the residents . This was published in the Galveston News in 1891 by Isaac Cline , director of the National Weather Bureau . Isaac Cline argued that the location of the city made it unlikely that a very strong hurricane would cause major flooding in the city. The mainland beyond Galveston was lower than Galveston. Water driven from the Gulf by a storm will first flood the Gulf.

The protective wall was never erected because of this report. As it turned out in September 1900, on the other hand, building developments that were carried out on the island had significantly increased the vulnerability of the city to possible storms. Sand dunes along the coast had been removed in the last decade of the 19th century to fill the lower parts of the island with this sand. With that, the city of Galveston had lost the little protection these natural barriers afforded it from the waves from the Gulf of Mexico .

Emergence

Due to the limited possibilities of weather recording in 1900, the location of the storm that destroyed Galveston on September 8th has not been definitively determined.

Reports from ships were still the only reliable source of storms brewing over the sea at the beginning of the 20th century. And since wireless telegraphy was just beginning to develop, these reports were not passed on until the ships docked in a port.

Today it is believed that the Galveston Hurricane, like most Atlantic storms, originated off the West African coast. Ship reports that observed an area with “unstable weather” on August 27, 1900 at 19 degrees north latitude and 48 degrees west longitude, halfway between Cape Verde and the Antilles , are seen as harbingers of the approaching storm .

Three days later, Antigua was hit by a violent thunderstorm, followed by a humid, warm and windless weather period, such as those that occur more often after a tropical cyclone has passed through . On September 1, US weather observers reported a medium-intensity storm southeast of Cuba .

September 2nd to 7th

| rank | hurricane | season | victim |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Galveston" | 1900 | 8000-12000 1 |

| 2 | "Okeechobee" | 1928 | > 2500 1 |

| 3 | Katrina | 2005 | 1836 |

| 4th | "Cheniere Caminada" | 1893 | 1100-1400 1 |

| 5 | "Sea Islands" | 1893 | 1000-2000 1 |

| 6th | "Florida Keys" | 1919 | 778 |

| 7th | "Georgia" | 1881 | 700 1 |

| 8th | Audrey | 1957 | 416 |

| 9 | "Labor Day" | 1935 | 408 |

| 10 | "Last Island" | 1856 | 400 1 |

|

1 estimated, total Source: NOAA |

|||

1900 had gone well for Galveston City up to that day in September. On April 21, the Texan Heroes Monument was inaugurated in memory of the Battle of San Jacinto . In May, the Galveston News published plans to expand the port, which would finally secure Galveston's economic supremacy, the cotton harvest had started on September 1st and Galveston was the port where the largest amount of cotton was handled in Texas. The Labor Day on September 3, was celebrated with a parade of dockworkers and cotton shippers. In its September 8th issue, the Galveston News proudly announced that the city's population has increased by 30 percent over the past decade.

On September 4, the Galveston branch of the National Weather Bureau received a message from headquarters in Washington, DC that a tropical storm was passing through Cuba. On September 5, Washington headquarters were certain that this moderate storm, accompanied by heavy rainfall, would move up the Atlantic coast and that the storm foothills would be felt as far as Norfolk , Virginia . It was also hoped the storm would end the long hot spell that had raged east of the Mississippi River for weeks in the United States , which had resulted in a number of heat deaths . The meteorologists of Cuba - despised by the meteorologists of the US National Meteorological Office for their interpretive weather forecasts - published in Cuban newspapers that the low pressure area of a hurricane was north of Cuba. One of the Cuban meteorologists took the view that the storm would hit the Texan coast and affect as far as San Antonio .

On Thursday, September 6th, the storm was reported northeast of Key West , Florida - a false report, but which confirmed the forecasts of the National Weather Bureau and to which all further reports were adjusted. It was believed that the tropical storm had moved from Key West to Tampa, Florida. In reality, a high pressure area blocked the hurricane's path north. The increasingly stronger storm was therefore diverted towards Galveston, which was 1,288 kilometers from Key West. The storms seen in Florida were just the offshoot of the emerging hurricane.

Only the ships that fought against their sinking from Thursday afternoon in the Gulf of Mexico could have corrected the misjudgment of the National Meteorological Office. The steamship Louisiana was launched from Port Eads in Louisiana in the direction of New York and was overtaken by the storm in the Gulf of Mexico. While the ship was shaken by gusts with an estimated wind speed of 240 kilometers per hour, Captain Halsey recorded the unusually low pressure of 973 hectopascals on the barometer - at sea level the pressure is normally 1013 hectopascals. Captain Simmons on the Pensacola read only 967 hectopascals. The storm was no longer a medium tropical storm - it had grown in strength very quickly over the heated Gulf of Mexico and was now clearly a hurricane. The ships fighting their sinking in the Gulf of Mexico, however, had no way of reporting their situation to the mainland, and the ships could only land after Hurricane Galveston had already destroyed.

On Friday morning, the day before the disaster struck Galveston, the headquarters of the National Weather Bureau corrected its assumptions about the course of the storm. It was becoming increasingly clear that the storm was still in the Gulf of Mexico area. The direction of the storm was still assumed to be north-westerly. Ships have already been missing on the western coast of Florida.

The regional meteorological offices were only allowed to publish weather warnings after consultation with the headquarters in Washington, and the headquarters in Washington now issued instructions to the branch in Galveston and the neighboring regions to hoist the storm flags so that the departing ships could anticipate unsettled weather point out in the Gulf of Mexico. The ship's captains, who asked the weather department about the expected weather, received different and sometimes reassuring messages from the staff there. The Cuban meteorologists, on the other hand, repeated their view in the Cuban newspaper La Lucha that a strong storm was moving towards Texas.

September 8th

On the morning of September 8th, the Galveston News appeared as usual: On page 10 there was a notice that the National Weather Bureau saw signs that the storm was about to sweep the Gulf of Mexico. But even the residents of Galveston, who read this hidden message, could not have concluded that there was any danger:

- The Meteorological Bureau employees do not expect any dangerous disturbance, but they cannot yet assess the extent of the storm or how it will develop when it reaches Texas. (Communication from Galveston News, September 8, 1900, quoted from Larson, p. 183)

The approaching hurricane drove the water in the Gulf of Mexico in front of it. While ships were stranded in Florida, the sea level in the western part of the Gulf rose significantly: In the course of the morning, sea water was already in the lower streets of Galveston. The residents still reacted calmly - the low-lying island had already survived many floods, and most of the houses were built on pillars. At the same time it was raining heavily and there was a strong north wind that drove the water out of Galveston Bay towards the island. In the course of the morning, possibly not until noon, Isaac Cline decided to issue a hurricane warning without authorization and without the consent of headquarters in Washington. However, very many people do not seem to have reached this point. From the eyewitness accounts, one can conclude that until the early afternoon - when corpses had long since drifted in the water near the beach and the massive bathhouses had been smashed by the waves - many residents of Galveston had no idea that a hurricane might be approaching their city . The inadequate communication options were fatal. Fathers of families were unsuspectingly eating lunch in the city's business district, while their wives and children, only two or three kilometers away, were desperately trying to escape from their homes near the beach.

The last train to reach the mainland from Galveston on September 8th left the station at 9:45 a.m. The train coming from Houston in the direction of Galveston arrived at the bridges to the island around twelve o'clock. At that time, the water almost reached the tracks. Nevertheless, the train continued its journey cautiously - on the island, however, the track bed was in places already so washed away by waves that the passengers had to get off halfway and wade through the water for a kilometer to change to a replacement train from the opposite direction . This replacement train was also only able to continue its journey slowly because the waves had washed flotsam onto the tracks. When they reached the Galveston station building, the first floor was already under water.

The 95 passengers who wanted to travel from Beaumont to Galveston were already in a less fortunate position at this point. When they arrived on the Bolivar Peninsula, the ferry that was supposed to cross the train and them to Galveston was no longer able to dock in the port due to the high waves. The engine driver tried to return to Beaumont by train, but found the tracks were already so badly flooded by the flood that the return journey was impossible. Ten of the train passengers sought refuge in the port's lighthouse together with the 200 residents of Port Bolivar . The rest of them stayed on the train, which over the next few hours became a deadly trap for each of them. When the passengers finally realized that the train, which looked so stable, offered no protection from the hurricane, the waves were already too high and the current too strong for them to be able to flee to the lighthouse.

The last message that reached the outside world from Galveston that day was released by the weather bureau. At 2:30 p.m., a telegraph sent a message to headquarters in Washington DC that half of the city's streets were under water. After that, the telegraph lines failed.

The report that the Galveston Meteorological Office was still able to telegraph to Washington DC painted an overly optimistic picture of the situation. The streets near the beach were no longer passable at that time, and there was no street on the island that did not have water. The higher the water level, the stronger the current was. Because of this current and the debris floating in it, roads were very quickly no longer passable. Those who were still able to leave their house fled into town and sought protection, especially in the houses, whose stone walls seemed to be able to withstand the ever stronger winds. In Isaac Cline's small stone house, 50 people took shelter from the wind and the tides. 32 of them died when the waves lifted the house from its pillars later that evening and overturned it like a ship.

The main work of destruction of the storm took place between 5:15 p.m. and 8:00 p.m. At 5 p.m. the Galveston Weather Bureau was already recording regular gusts of hurricane force; at the same time the air pressure began to drop rapidly. The lowest recorded air pressure that evening was 958 hectopascals. In the meteorological office, wind speeds of 160 kilometers per hour were measured; then the wind tore the anemometer off the roof. Investigations later concluded that winds of at least 190 kilometers per hour were constant between 5:15 p.m. and 7:00 p.m., and that the lowest air pressure was likely only 930 hectopascals. Gusts of up to 300 kilometers per hour rushed through the city. The wind tore away the ships moored in the harbor, lifted roofs, crushed house walls, carried away one floor after the other in multi-storey houses and threw bricks, shingles and boards through the air. A meter-long and 15 cm wide wooden board was hurled against the English steamer Comino by the wind with such force that it pierced the centimeter-thick iron plates of the ship's hull. In the streets, people were beheaded by shingles or badly injured by splinters of wood.

The tidal waves were even more devastating than the wind. During the twenty-four hours before the Galveston hurricane struck the city, Galveston had had north winds. This strong north wind had driven the water from the sixty-square-kilometer bay beyond Galveston onto the island. In the city of Galveston, therefore, two floods collided: the water driven out of the bay towards the gulf and the currents due to the rise in the water level in the gulf. At the same time, the prevailing north wind throughout Saturday morning held back most of the tidal wave from the Gulf on the sea. Erik Larson , who dedicated a book to the Galveston disaster in 1999, compared the situation in the Gulf to a compressed spring. If the north wind changed its direction, this tidal wave would roll towards the city. That happened around 6:30 p.m. when the water level rose by 1 to 1.20 meters within a few seconds.

- Closer to the beach… the sea had piled up a wall of rubble three stories high and several kilometers long. It consisted of houses, parts of houses, and roof ridges that floated on the water like the hulls of de-masted ships; In addition, there were landauers, singles, pianos, toilets, red velvet curtains, prisms, photographs, parts of wicker chairs and of course corpses - hundreds, maybe thousands. The wall was so high, so massive that, like a kind of quay wall, it absorbed the direct impact of the huge waves rolling in from the gulf. These pushed the rubble wall to the north and west. It moved slowly but inexorably, and where it came it devoured all buildings and all life. (Larson, pp. 235f).

The hurricane hit Galveston at an angle of 90 degrees. Because of this direction, he directed the onshore current directly into the city. When the sea level rose so quickly, there were no more escape routes for many residents.

The storm had passed Galveston that night. He moved on to Oklahoma and then Ohio . Its gusts reached hurricane strength in Chicago and Buffalo , and so many telephone poles were destroyed in the entire Midwest and northern third of the United States that all communications in these parts of the country collapsed.

On September 12, the storm was over the region north of Halifax , Nova Scotia and turned from there in the direction of the North Atlantic. With wind speeds that still reached more than 110 kilometers per hour, he haunted Prince Edward Island .

The extent of the destruction

"Washington, DC

Sept. 9, 1900

To: Manager, Western Union

Houston, Texas

Do you hear anything about Galveston?"

Chief, US Weather Bureau

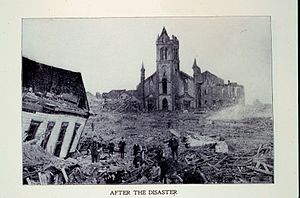

In 1900 the highest natural elevation on the island was just 2.6 meters above sea level. The tidal wave that the hurricane winds drove out of the gulf in front of them was 4.6 meters high and washed over the entire island. The buildings, which the wind had not destroyed, were lifted from their foundations and pillars and shattered by the waves. Over 3,600 houses in the city were destroyed. On the morning of September 10, a long, high wall of rubble lined the ocean shore.

With the bridges and telegraph lines destroyed, the outside world learned only very gradually of the magnitude of the disaster that had struck Galveston. One of the few undestroyed ships in the port of Galveston landed with six emissaries on Sunday morning at eleven o'clock in the small town of Texas City on the western side of Galveston Bay, from where they traveled on to Houston . Sixteen hours later, at three a.m. the next day, they sent a brief message from the Houston Telegraph Office to Texas Governor Joseph D. Sayers and US President William McKinley : I have been deputized by the mayor and Citizen's Committee of Galveston to inform you that the city of Galveston is in ruins. (I have been assigned by the Mayor and Galveston City Council to inform you that Galveston City has been destroyed). The news put the death toll at 500 - in Houston, the number was thought to be an exaggeration.

The victims

Even without the Galveston envoys, Houston policy-makers were aware that a severe storm had raged the coast. As early as Sunday morning, soldiers were sent to Galveston as rescue workers by rail and ship. The trains returning after the rescue workers had dropped off brought the first news of the natural disaster to Houston. At 11:25 p.m. on Sunday, September 9, the local head of the Western Union telegram sent Willis Moore, the head of the US National Meteorological Office, to inform:

- First news of Galveston received by trains - Trains cannot approach the Galveston Bay coast more than six miles as prairie is littered with debris and dead bodies. Two hundred bodies counted from the train. Big steamship stranded two miles inland. There was nothing to be seen of Galveston. To fear high numbers of victims and severe destruction. Clear and sunny weather with a light southeast breeze.

When the rescue workers couldn't get any further by train, they requisitioned the few lifeboats and sailing ships that were still in use and used them to cross over to the island of Galveston. They had to make their way through a waterway in which countless corpses were floating. They found a hundred corpses alone in the tops of a small cedar grove on the island. Mountains of rubble covered most of the urban area.

How many people fell victim to the hurricane could no longer be clarified. Most official reports assume 8,000 victims - one in five residents on Galveston Island would have died. Most of them drowned or were slain by the rubble that drove the sea. Many survived the hours of the hurricane and died over the next few days trapped in rubble where the inadequately equipped rescue workers could not reach them.

The number of victims was so numerous that normal burials were not possible. A strong smell of putrefaction hung very quickly over the city, which experienced daytime temperatures of up to 38 ° C in the days after the storm. Initially, ships took the bodies out to sea and sank them there. However, the current of the gulf carried the dead back to the beach, so it was finally decided to cremate the dead. Pyres were set up where the dead were found. The last pyre burned until the end of September.

The Galveston hurricane of 1900 thus cost more lives overall than the three hundred hurricanes that historically struck the United States together.

After the storm

Many of the storm survivors used US Army tents as first makeshift shelters. They erected them along the beach, and their number was so great that it was called the White City on the Beach . Some began to build so-called storm lumber houses, using the recyclable materials from the rubble washed up on the beach.

On September 12th, mail reached Galveston for the first time. The next day a basic supply of water was ensured, and Western Union was able to ensure a minimum of telegraphic service again. After just three weeks, the port was cleared and repaired enough to start handling cotton again.

Before September 8, 1900, Galveston was considered one of the most beautiful cities in the United States. The city was called the New York of the South . Galveston was well positioned before the storm to become one of the largest cities in the United States. After the destruction, economic forces increasingly shifted to Houston, which also benefited from the beginning oil boom over the next few years . A canal dug into Houston between 1909 and 1914 buried city residents' hopes that Galveston could regain significant economic strength due to its port. Galveston, whose population had grown by nearly 30 percent in the 10 years from 1890 to 1900, stopped growing.

Today Galveston is an insignificant city Houston residents like to spend their weekends in or where they keep their beach houses. The author Erik Larson referred to today's Galveston as the Houston bathing area . The houses that weathered the storm have been renovated and now give the city a Victorian touch that is appreciated by tourists.

The National Meteorological Office, which consistently underestimated this storm and did not react to the warnings of the Cuban colleagues, emerged largely unscathed from this incident. Isaac Cline, the head of the local meteorological office, who issued a hurricane warning on September 8th and who in his report to the National Meteorological Office claimed to have warned thousands of people in the immediate vicinity of the beach of the coming hurricane (which at least his biographer Erik Larson doubts ), was considered one of the heroes of the storm. He was promoted from the National Weather Bureau.

Protective measures

In order to avoid future storm damage from comparable hurricanes, a number of construction measures have been taken on the island. In 1902, work began on building the first 4.8 kilometers of a 5.2 meter high protective wall, the so-called Galveston Seawall . A storm-proof bridge connected the island to the mainland.

In addition, it was decided to raise the city's soil level. Sand was used to raise the city a total of 5.2 meters. 2,100 buildings were moved in the process, including the 3,000-ton St. Patrick's Church. The ramparts and the lift kit of the city was by the 2001 American Society of Civil Engineers for "National Historical Civil Engineering Landmark" appointed.

In 1915, the city was hit again by a hurricane , both in strength and in course of the 1900. Even though 215 people lost their lives in this storm, the new protective wall in particular proved its effectiveness. The dam that exists today is 16 kilometers long and has long since become a tourist attraction. It still has a protective function; However, it is above all the current possibilities of weather forecasting that ensure that the city can better prepare for a storm and is no longer hit to such an extent. Even so, Galveston is still considered to be one of the cities that could suffer great damage from a strong hurricane.

In September 2005 it was feared that Hurricane Rita , the strongest cyclone ever observed in the Gulf of Mexico , could hit Galveston with full force. However, Rita passed Galveston and reached the coast on September 24, 2005 at 2:38 am local time on the Texas-Louisiana border near the town of Sabine Pass. As Rita passed in the east, the north wind prevailed, which made for a weak, two-meter high tidal wave. The existing dyke wall held up. At the beginning of the hurricane, a fire broke out in the city center, but the fire department was able to put it out before it continued to spread.

Aftermath

| rank | hurricane | year | Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Great hurricane of 1780 | 1780 | 22,000+ |

| 2 | Hurricane Mitch | 1998 | 11,000-18,000 |

| 3 | Galveston Hurricane 1900 | 1900 | 6,000-12,000 |

| 4th | Hurricane Fifi | 1974 | 8,000-10,000 |

| 5 | San Zenon Hurricane | 1930 | 2,000-8,000 |

| 6th | Hurricane flora | 1963 | 7,186-8,000 |

| 7th | Pointe-à-Pitre | 1776 | 6,000+ |

| 8th | Newfoundland hurricane | 1775 | 4,000-4,163 |

| 9 | Okeechobee hurricane | 1928 | 3,375-4,075 |

| 10 | San Ciriaco hurricane | 1899 | 3,064-3,433 + |

| Ranking according to the highest assumed number of victims. | |||

The short film Searching Ruins on Broadway, Galveston, for Dead Bodies, made in 1900, shows the search for the dead after the hurricane.

Almost a hundred years after the destruction of Galveston, Erik Larson published Isaac's Storm: A Man, A Time, and the Deadliest Hurricane in History - published in German under the simpler title Isaacs Sturm . This so-called factual novel processes numerous eyewitness reports, has won several awards and has been translated into numerous languages. At the center of his story was Larson Isaac Cline, the head of the local weather bureau, who for him was the symbol of the era when “ hubris made people believe that they could defy nature itself”. He equates the catastrophe of the city of Galveston with the sinking of the Titanic , which happened only a few years later, mainly due to human overestimation.

The folk song Wasn't That A Mighty Storm (author unknown) is about the Galveston Hurricane. He was made famous by Eric Von Schmidt and Tom Rush and is still part of the repertoire of the singer / songwriter James Taylor (including on the album Other Covers (2009)).

literature

- Erik Larson: Isaac's Storm: The Drowning of Galveston 8th September 1900. Random House, New York 1981, ISBN 978-0-375-72475-6 .

- German translation: Isaacs Sturm . Translated from the American by Bettina Abarbanell . Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2000. ISBN 3-596-50644-1 .

- Patricia Bellis Bixel, Elizabeth Turner: Galveston and the 1900 Storm. University of Texas Press, Austin 1992, ISBN 978-0-292-70883-9 .

- Patricia Bellis Bixel, Elizabeth Hayes Taylor: Galveston and the 1900 Storm: Catastrophe and Catalyst. University of Texas Press, Austin 2000. ISBN 0-292-70883-1 .

- Casey Edward Greene, Shelly Henley Kelly (Eds.): Through a Night of Horrors: Voices from the 1900 Galveston Storm. Texas A&M University Press, College Station 1900, ISBN 978-0-89096-961-8 .

- Barbara Büchner: Hurricane , 2007. ISBN 978-3-86506-185-0 .

- Al Roker: The Storm of the Century: Tragedy, Heroism, Survival, and the Epic True Story of America's Deadliest Natural Disaster: The Great Gulf Hurricane of 1900. William Morrow & Company, New York 2016, ISBN 978-0-06-236466 -1 .

Web links

- NOAA : Interactive map of the storm's track

- NOAA: Map of the peak levels of the storm flood

- NOAA: Transcripts of original documents (Clines official report of 23 September 1900 to the Weather Bureau and formal recognition)

- Galveston and Texas History Center (archival department) of the Rosenberg Library: online exhibition on the effects of the storm, including many photographs and manuscripts

- Texas State Historical Association: Galveston Hurricane of 1900. From: The New Handbook of Texas.

- Galveston County Daily News: Website for Hurricane of 1900 (Engl.)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The deadliest, costliest and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts) ( English , PDF) In: NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6 . National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. August 10, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2017.