Robert de Clifford, 1st Baron de Clifford

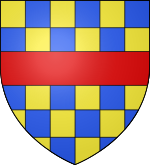

Robert de Clifford, 1st Baron de Clifford (April 1274 - June 24, 1314 near Bannockburn ) was an English magnate and military.

Origin and youth

Robert de Clifford came from an old Anglo-Norman noble family who were among the most powerful barons of the Welsh Marches . His father was Roger de Clifford and his mother was Isabella de Vieuxpont . Through his father's marriage to Isabella, who together with her sister Idonea inherited the northern English rule of Westmorland , the Cliffords rose to become one of the most important northern English barons. When Robert was eight years old, his father was killed in 1282 during King Edward I's second campaign against Wales in the Battle of Menai Strait . Guardianship for the boy was apparently given to Edmund, 2nd Earl of Cornwall , a cousin of the king, but ultimately his mother remained responsible for him. This gave her son for education to the powerful Gilbert de Clare, 6th Earl of Gloucester . After the death of his grandfather Roger de Clifford in 1286, Robert became his heir. After his mother died in 1291, Edmund of Cornwall took over again the guardianship. In 1294, Clifford is said to have been a ward of King Edward I , and in the spring of 1295 he accompanied the king in Wales, where he put down a Welsh rebellion . His inheritance was transferred to him on May 3, 1295, but more than fifteen years later he was still litigating properties that had fallen into strange hands during his long minority.

War against Scotland

Clifford's efforts to obtain his full legacy were hampered by the long war against Scotland . As a knight of the royal household, he took part in numerous campaigns against Scotland, in addition to which he held numerous offices in occupied Scotland and in northern England. At the beginning of the war in 1296 he accompanied the king to Scotland. After a widespread Scottish revolt against English rule in the spring, the king appointed him in July 1297 as the commander of the royal castles in Cumberland . Together with Henry Percy , he had drawn up a contingent in the northern English border counties and with this army quickly moved through Annandale and Nithsdale to Ayr . At Irvine , James the Stewart and William Douglas surrendered . He and the Scottish Treasurer Hugh Cressingham refused a further advance , instead they waited for reinforcements under the command of the governor Earl Warenne . After Warenne's defeat at the Battle of Stirling Bridge , Clifford led a destructive Chevauchée to Annandale in late 1297 . There his cavalry was caught in a Scottish ambush, in which they suffered heavy losses, but could defeat the Scots. During the Chevauchée, the English burned ten villages. During another Chevauchée in February 1298, he burned Annan down. On July 22, 1298, Clifford fought as Knight Banneret of the Knights of the Royal Household in the Battle of Falkirk . In gratitude for his support, the king had appointed him administrator of Nottingham Castle and judge of the royal forests north of the Trent on July 7, 1298 . On September 26, 1298 he received the Scottish Caerlaverock Castle from the king and the possessions of William Douglas, who died in English captivity. However, this led to a feud between the Cliffords and the Douglas that lasted for over 100 years. On November 25, 1298, the king appointed him royal representative in north-west England and in the Scottish border areas of Roxburghshire , which Clifford remained until at least July 1299.

On 29 December 1299 the King Clifford appointed by a Writ of Summons in the parliament , making it the title of Baron de Clifford received. From now on he regularly took part in parliamentary sessions, the last time in November 1313. In 1300 he accompanied the king on the campaign against Caerlaverock Castle. He also fought in Scotland in the winter of 1301 to 1302. When he again accompanied the king on a campaign to Scotland in 1304, he took part in a successful attack on the leaders of the Scottish rebellion at Peebles around March 1 . Later that year he was among the troops of the heir to the throne with whom he besieged Stirling Castle . From 1302 to 1303 and from 1305 to 1307 he administered the vacant Diocese of Durham . In the winter of 1303 to 1304 he led together with John Seagrave and William Latimer another Chevauchée to Lothian , where they beat a Scottish troop under William Wallace and Simon Fraser . In March 1306 he administered the Scottish Selkirk for the king . Shortly thereafter, the king made him one of the commanders who attacked the rebellious Robert the Bruce . In the spring of 1307, in Galloway , Clifford pursued Robert the Bruce , who had risen to be King of the Scots. However, he could not prevent James Douglas , the son of William Douglas, recaptured Douglas Castle and slaughtered the castle crew left behind by Clifford.

Expansion of his own possessions

Despite his extensive service to Edward I, whom he served loyally, Clifford managed to further expand his own position in northern England. In May 1306 he was handed over by the King Hart and Hartlepool in the Diocese of Durham, which had previously been possessions of Robert the Bruce. In February 1307 the king gave him the confiscated lands of Sir Christopher Seton in Cumberland. The focus of his possessions, however, remained Westmorland. There he had already been able to expand his estates in 1298 by purchasing the estate of Brough Sowerby . In addition, he managed to build a loyal following among the local gentry . Several Westmorland nobles served repeatedly under his leadership in the wars against Scotland. In 1300 King Edward I visited him with his entourage, and Clifford demonstrated his power with the expansion of Brougham Castle , for which the king gave him the right to fortify in 1309. Through the marriage of his daughter Idonea to Henry , a son of his brother-in-arms Henry Percy, 1st Baron Percy, Clifford consolidated his position within the northern English nobility.

Confidante of Edward II.

As a confidante of Edward I, Clifford was one of the four leading barons whom the king asked on his deathbed in July 1307 to crown his son Edward as his successor as soon as possible; the king presumably commissioned him to return the exiled pier Gaveston , the friend and favorite of the heir to the throne, to prevent England. The heir to the throne greatly valued Clifford's military experience and appointed him Marshal of England . In this position he was responsible for Eduard's coronation, which took place on February 25, 1308. However, on January 31, he had been a signatory to the Boulogne Agreement , a letter of protest addressed to the king, and on March 12, 1308, he was replaced as Marshal, administrator of Nottingham Castle and judge of the Forests north of Trent. Still, he is unlikely to lose the King's favor, as on August 20 he was appointed Military Commander and Chief Guardian of Scotland . To this end, with the support of the king, he concluded negotiations with his aunt Idonea and her second husband John Cromwell on October 13, 1308 , which led to the reunification of Westmorland, which had been divided since the 1260s. Presumably the king wanted to strengthen Clifford's position in northern England in the face of growing Scottish resistance. Between March and September 1310 he received the Honor of Skipton and Skipton Castle in Yorkshire through three royal grants . As a result, Clifford had Skipton Castle expanded.

Clifford continued to serve regularly in Scotland under Edward II. On October 26, 1309 he was appointed administrator of the Scottish Marches at Carlisle , and on December 20, 1309 he was appointed Warden of Scotland , including 100 men in arms and 300 foot soldiers. He gave up this office on April 1, 1310, but in July he was again in Scotland. In December 1310 he negotiated with Robert the Bruce in Selkirk. On April 4, 1311 Edward II appointed him administrator of Scotland south of the Forth .

Involvement in the aristocratic opposition to the king

However, due to his increasing involvement in the dispute over the royal favorite Piers Gaveston, he neglected his duties in Scotland. The king had given his favorite, who had returned to England against the wishes of the late Edward I, the Honor of Penrith in Cumberland in December 1310 . Clifford may have feared that Gaveston might become a rival in northern England, but presumably he was also an opponent of Gaveston mainly because of King Edward I's last wish and the general rejection of Gaveston by the barons. Although he was not one of the Lords Ordainers who tried to restrict the rule of the king, when Gaveston illegally returned from his renewed exile, contrary to an express prohibition, Clifford was one of the barons who hunted him. In the spring of 1312 he and Henry Percy, the Earl of Warwick and the Earl of Pembroke besieged Scarborough Castle , where Gaveston had withdrawn. In pursuit of Gaveston, however, he had presumably taken jewels and valuables in Newcastle that Gaveston and the king had left behind on their flight and which were only returned to the king after Clifford's death. After Gaveston was executed on June 19, 1312 by a group of magnates led by the Earl of Lancaster , Clifford was one of the negotiators who negotiated a settlement between the king and the magnates under Lancaster. On October 14, 1313, the King pardoned Lancaster and the other barons involved in Gaveston's execution, and two days later Clifford was pardoned for persecuting Gaveston.

Death in the Battle of Bannockburn

After the king had superficially settled the domestic political crisis, he undertook a large-scale campaign against Scotland in the summer of 1314. On June 10, 1314, Clifford joined the royal army in Berwick. During the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, on the first day of the battle, he led a unit of selected knights with Henry de Beaumont who tried to relieve the besieged Stirling Castle . The mounted attack was repulsed by the Scottish Schiltrons , and Clifford's failure against the Scottish infantry was viewed as shameful. Perhaps to restore his honor, therefore, he was part of the vanguard on the second day of the battle and was killed in battle. Clifford's body was recovered by the Scots and first brought to Carlisle. Clifford had been considered one of the most experienced and bravest knights and had a good reputation among the Scots too. The victorious Scottish King Robert the Bruce did not demand a ransom from Clifford's family for the body. His body was probably buried in Shap Abbey in Cumberland, where he had donated a chapel for the salvation of his parents' souls.

The Scottish poet John Barbour praised Clifford as a valiant knight, and the Song of Caerlaverock , which Clifford himself may have commissioned, praises him as a wise, wise, and honorable baron.

Family and offspring

In 1295 Clifford had married Maud de Clare , the eldest daughter of Thomas de Clare, Lord of Thomond , the brother of the Earl of Gloucester, with whom he grew up. Clifford had several children with his wife, including:

- Roger († 1322)

- Robert († 1344)

- Margaret († 1382) ⚭ Peter Mauley, 3rd Baron Mauley

- Idonea ⚭ Henry Percy, 2nd Baron Percy

Since his sons were minors when he died, Sir Bartholomew de Badlesmere became the guardian of his eldest son and heir Roger. His widow Maud was forcibly kidnapped in 1315 by Jack the Irishman, the administrator of Barnard Castle , but was freed by other knights. She married Robert de Welle, one of her liberators, for the second time.

Web links

- Henry Summerson: Clifford, Robert, first Lord Clifford (1274-1314). In: Henry Colin Gray Matthew, Brian Harrison (Eds.): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , from the earliest times to the year 2000 (ODNB). Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-861411-X , ( oxforddnb.com license required ), as of 2004

Individual evidence

- ^ Michael Prestwich: Edward I. University of California, Berkeley 1988, ISBN 0-520-06266-3 , p. 153

- ^ Geoffrey WS Barrow: Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland . Eyre & Spottiswoode, London 1965, p. 119.

- ^ Michael Prestwich: Edward I. University of California, Berkeley 1988, ISBN 0-520-06266-3 , p. 477

- ^ Geoffrey WS Barrow: Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland . Eyre & Spottiswoode, London 1965, p. 135.

- ^ Geoffrey WS Barrow: Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland . Eyre & Spottiswoode, London 1965, p. 220.

- ^ Michael Prestwich: Edward I. University of California, Berkeley 1988, ISBN 0-520-06266-3 , p. 499

- ^ Michael Prestwich: Edward I. University of California, Berkeley 1988, ISBN 0-520-06266-3 , p. 557

- ^ Michael Altschul: A baronial family in medieval England. The Clares. The Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore 1965, p. 47

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Clifford, Robert de, 1st Baron de Clifford |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Clifford, Robert de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English magnate and military |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 1274 |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 24, 1314 |

| Place of death | at Bannockburn |