Battle of Sissek

| date | June 22, 1593 |

|---|---|

| place | Sisak , then Austria |

| output | Victory of the Austrians |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

Ruprecht von Eggenberg |

Setting Hassan pacha † ( Beylerbey Bosnia) |

| Troop strength | |

4,300–5,800 soldiers

|

12,000-16,000 soldiers |

| losses | |

|

Dead: 500 |

Dead: 8,000 killed or drowned |

Sissek - Călugăreni - Mezőkeresztes - Schellenberg - Mirăslău - Guruslău

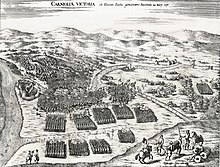

In the Battle of Sissek , also the Battle of Sisak ( Croatian fortress near today's Sisak ) at the confluence of the Save and Kupa rivers , Habsburg troops under the three commanders Ruprecht von Eggenberg , Andreas von Auersperg and Toma Erdődy met Ottoman troops on June 22, 1593 Troops under Telli Hassan Pascha , the Beylerbey of Bosnia .

In 1591 and 1592 there had already been two failed attempts by the Ottomans to take the fortress Sisak, but in 1592 they managed to conquer the strategically important fortress Bihać . From June 15, 1593, Hassan Pascha and his army crossed the then border river Kupa without a formal declaration of war and besieged the fortress Sisak again. The garrison in Sisak was commanded by Blaž Đurak and Matija Fintić, both sent from the Archdiocese of Zagreb .

A relief army under the command of Ruprecht von Eggenberg had been hastily assembled to lift the siege. He was subordinate to Croatian troops under the command of the Ban of Croatia Tamás Erdődy and larger troop contingents from the Duchy of Carniola and the Duchy of Carinthia under the command of Andreas von Auersperg . On June 22nd, they finally launched a surprise attack on the besiegers. The resulting battle ended in a catastrophic defeat for the local Ottoman forces and sparked the Long Turkish War .

background

Although neither the government of the Ottoman Empire nor that of the Habsburg Monarchy were interested in any major conflict, the peace between the two empires was extremely fragile. The peace of 1547 , originally concluded for only 5 years , had already been renewed four times, but larger raids on the other national territory took place again and again. The 1592 peace treaty of Adrianople did little to change that. Ottoman Akıncı (irregular, light cavalry, German also Renner and Brenner ) on the one hand and Christian Uskoks (irregular light infantry) carried out raids and raids again and again. Even on the Croatian military border , despite the peace treaty, there were repeated minor armed clashes. The Habsburg part of Croatia at that time consisted of only 16,800 km² with around 400,000 inhabitants.

The constant conflicts on the border bleeding the country to the core, but at the end of the 16th century Croatian fortresses were mostly able to withstand Ottoman advances. Ottoman troops repeatedly crossed the Una and the Save to raid fortresses and cities in the Habsburg part of Croatia. On October 26, 1584, a smaller Ottoman force was wiped out in a battle near Slunj , and on December 6, 1586 at Ivanić-Grad . The frequency of the Ottoman raids increased, however, and the Croatian nobles fought largely without the support of the Habsburgs.

Prelude

Already in August 1591 Telli Hassan Pascha, the Ottoman vizier and Beylerbey of Bosnia, had invaded Habsburg Croatia without a declaration of war, had reached the fortress of Sisak, but was turned away there after a four-day battle. Thomas Erdödy , the Habsburg ban of Croatia, then carried out an attack in the Moslavina region in the Ottoman part of Croatia. Hassan Pasha attacked again in the same year and captured the town of Ripač on the Una River. This advance caused Erdödy to convene the Croatian parliament in Zagreb on January 5, 1592 and to declare a general mobilization for the defense of the country. In view of the 9-year peace treaty of Adrianople concluded in 1590, the attacks by Hassan Pasha seem to have been against the interests and goals of the Ottoman central government in Constantinople and are more likely to have had the purpose of looting and stealing booty, and possibly also of the raids to end the Christian Uskoks.

In June 1592, Hassan Pascha captured Bihać and set out for Sisak a second time. The capture of Bihać caused fear in Habsburg Croatia, as this fortress had defended the border with the Ottoman part for decades. On July 19, 1592, Hassan Pascha attacked and set fire to a military camp in the Croatian village of Brest Pokupski near Petrinja , which Ban Erdödy had built there a few months earlier. The camp had a crew of 3,000 men, while the Ottomans were able to muster 7,000–8,000 men. From July 24th, the Ottomans again besieged Sisak, but they had to break the siege 5 days later after fighting and heavy losses and to withdraw from the Turopolje region . All of these events ultimately encouraged Emperor Rudolf II to make greater efforts to stop the Ottomans. At first, the winter ended all further actions.

The battle

In the spring of 1593, Beylerbey Telli Hassan Pascha gathered a large army near Petrinja , crossed the border river Kupa again and made his third attempt to conquer Sisak. His army consisted of 12,000 to 16,000 men from the Sanjaks of Klis , Lika , Zvornik , Herzegovina , Požega , Orahovac and Pakrac . The crew of the Sisak Fortress consisted of a maximum of 800 men under the command of Matija Fintić, who however died on June 21 and was replaced by Blaž Đurak, both sent by the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Zagreb. The fortress was fired at with heavy artillery and a request was made to Ban Erdödy. The Habsburg relief army under Eggenberg, Erdödy and Auersperg arrived near Sisak on June 21. It consisted of about 4,000 to 5,000 cavalry and infantry. The Ottoman historian Mustafa Naima writes that after all preparations for the battle had been completed, Hassan Pasha ordered his Gazi Hodscha Memi Bey to cross the river and explore the opposing forces. He reported that the battle would end in defeat given the superiority of the Habsburgs (presumably because of the larger amount of cannons and ammunition). Naima wrote that Hassan Pasha, who was known as a fearless leader and was playing chess at the time , exclaimed in response: Curse you, you despicable villain! To be afraid of numbers: get out of my sight! . Then he mounted his horse, mobilized his troops and let them cross the newly built bridges.

On June 22nd, between eleven and twelve o'clock, the combined forces of Erdödy and Auersperg attacked the Ottomans. Erdödy's troops made up of Croatian hussars and infantry attacked first. The first attack could be repulsed by the Ottoman cavalry. But then Auersperg's and Eggenberg's troops intervened and forced the Ottomans to retreat to the Kupa River. Hassan Pasha's force was eventually trapped in a corner between the Odra and Kupa rivers when Habsburg-Croat troops from Karlovac took the Ottoman bridge over the Kupa. The garrison of Sisak under Blaž Đurak carried out a sortie and attacked the Ottoman besiegers of Sisak. Trapped between the Austrian armies, the Ottomans' retreat turned into chaotic flight. Many tried to reach their camp by swimming through the Kupa River. Most of the Ottoman forces, with almost all of their leaders, were eventually gutted or drowned in the river.

The battle lasted about an hour and ended in a total defeat for the Ottomans. Among the Ottoman leaders who perished was Mehmed, the bey of the Sanjak Herzegovina, a nephew of Sultan Murad . In addition, the beys of the Sanjaks from Pakrac, Zvornik (Hassan Pascha's brother), Požega, Orahovac and Klis died. Only the bey of the Lika sanjak escaped. The total losses were approximately 8,000 drowned or killed Ottomans. The winners captured 2,000 horses, 10 Ottoman war flags, as well as cannons and ammunition. The Austrian losses, on the other hand, were small. A report by Andreas von Auersperg of June 24th, 1593 to Archduke Ernst of Austria names only 40–50 dead among his troops.

Aftermath

Ban Thomas Erdödy wanted to use the victory to conquer Petrinja , where the remnants of the Ottoman army had fled. But Commander-in-Chief General von Eggenberg was of the opinion that the provisions of his army were insufficient and so the attack was not carried out.

Europe reacted delighted to the reports of the victory at Sissek. Pope Clement VIII praised the Christian military leaders and sent a letter of thanks to Ban Erdödy, while King Philip II of Spain made him Knight of the Order of Santiago . The Archdiocese of Zagreb had a memorial chapel built in the village of Greda near Sisak and decreed that a thanksgiving mass should be held in Zagreb every June 22nd. Hassan Pasha's mantle was given to Ljubljana Cathedral . Blaž Đurak, the commander of the garrison in Sisak Fortress, was rewarded by the Croatian Parliament for his contribution to the victory.

When news of the defeat reached Constantinople, high military leaders and the Sultan's sister, whose son Mehmed had died in battle, demanded vengeance. Although Hassan Pasha's actions had not been coordinated with the Sublime Porte and also ran counter to its interests and policies, the Sultan was of the opinion that such a shameful defeat, even by a subordinate who had acted on his own, would not be accepted unpaid could be. In the same year, Sultan Murad III declared. Emperor Rudolf II launched the war, which finally went down in history as the Long Turkish War and took place mainly in the areas of Croatia and Hungary. The Sultan died in 1595, but the war dragged on through the terms of office of his two successors, Mehmed III. (1595-1603) and Ahmed I. (1603-1617).

During the Long Turkish War, the Ottomans finally managed to take Sisak. On August 24, 1593, they took advantage of the absence of large Habsburg forces and besieged the fortress, which at that time was only defended by about 100 men. After heavy cannon fire, they managed to break through the walls by August 30th, after which the fortress surrendered. Sisak was liberated on August 11, 1594 when Ottoman forces fled and set the fortress on fire. The Long Turkish War finally ended on November 11, 1606 with the peace of Zsitvatorok , which also marked the first stop of Ottoman expansion towards Central Europe since the battle on the Krbava field and stabilized the border for almost half a century. Inner Austria with the duchies of Styria , Carinthia , Carniola and the county of Gorizia remained free from Ottoman rule. Croatia was also able to maintain its independence and even managed to make even smaller territorial gains after the peace treaty, such as B. Petrinja , Moslavina and Čazma . It is also important to mention that this first severe Ottoman defeat in the northwestern Balkans also shook the faith of the Christian Orthodox subjects in their Ottoman rulers. Serbs and Wallachians , in particular , emigrated to Habsburg-controlled areas or even rose up to open rebellion .

Since the battle took place in Croatia and Croatians also provided a large part of the soldiers, the battle also plays an important role in the history of Croatia. For example, the Croatian government B. 1993 a commemorative stamp with the title "Victory at Sisak 1593" (Croat. Pobjeda kod Siska 1593) out. The traditional ringing of the small bell of the Zagreb Cathedral at 2:00 p.m. is a token of the commemoration of this battle, as the Archbishop had also borne a large part of the costs of building the Sisak fortress.

Since many soldiers from neighboring Carniola also took part in the battle, it also plays a role in Slovenian history . On June 22, 1993, the Slovenian government issued three commemorative coins and one commemorative token commemorating the 400th anniversary of the Battle of Sissek.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Vjekoslav Klaić : Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća , Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 496

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein : Sisačka bitka 1593 , Zagreb, 1994, p. 104

- ↑ a b c d Ive Mažuran: Povijest Hrvatske od 15. stoljeća do 18. stoljeća , p. 146

- ↑ a b c d e Ferdo Šišić : Povijest Hrvata; pregled povijesti hrvatskog naroda 600 - 1918 , p. 305-306, Zagreb ISBN 953-214-197-9

- ^ A b Oto Luthar: The Land Between: A History of Slovenia (Peter Lang GmbH, 2008), p. 215

- ^ A b Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall , History of the Ottoman Empire. Vol.4: From the accession of Murad the Third to the second dethronement of Mustafa the First 1574–1623 , Budapest: CA Hartleben, 1829, p. 218 including footnote with references to strongly differing numbers in Turkish sources

- ↑ József Banlaky , A Magyar nemzet hadtörténelme; A sziszeki csata 1593 június 22.

- ↑ Klaus-Peter Matschke: The cross and the half moon. The history of the Turkish wars. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2004, ISBN 3-538-07178-0 , p. 292 f.

- ↑ a b Alexander Mikaberidze : Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia , 2011, p. 188

- ↑ Gábor Ágoston, Bruce Alan Masters: Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire , Infobase Publishing, 2009, p. 164

- ↑ a b Nenad Moačanin: Some Problems of Interpretation of Turkish Sources concerning the Battle of Sisak in 1593 , in: Nazor, Ante et al. (ed.), Sisačka bitka 1593 ( Memento of the original from July 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Proceedings of the Meeting from June 18-19, 1993. Zagreb-Sisak (1994); pp. 125-130.

- ^ Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća , Knjiga peta, Zagreb 1988, p. 480

- ^ Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća , Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 483-486

- ↑ Hivzija Hasandedić: Muslimanska baština u istočnoj Hercegovini (Muslim heritage in eastern Herzegovina) . El-Kalem, Sarajevo, 1990, p. 168.

- ↑ Mustafa Naima: Annals of the Turkish Empire from 1591 to 1659 of the Christian Era . Oriental Translation Fund, 1832, pp. 14-15.

- ^ A b Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća, Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 494-495

- ^ Radoslav Lopašić: Spomenici Hrvatske krajine: Od god. 1479-1610, Zagreb, 1884, p. 179-180

- ^ Radoslav Lopašić: Spomenici Hrvatske krajine: Od god. 1479-1610, Zagreb, 1884, p. 182-184; General Andrija Auersperg izvješćuje nadvojvodu Ernsta o porazu Turaka pod Siskom.

- ^ Oto Luthar: The Land Between. A History of Slovenia. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-57011-1 , p. 215.

- ^ A b Vjekoslav Klaić: Povijest Hrvata od najstarijih vremena do svršetka XIX. stoljeća , Knjiga peta, Zagreb, 1988, p. 497

- ↑ Ivo Goldstein: Sisačka bitka 1593 , Zagreb, 1994, p. 73

- ↑ a b Ive Mažuran: Povijest Hrvatske od 15. stoljeća do 18. stoljeća , p. 148

- ^ Stanford J. Shaw, History of the Ottoman empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. 1: Empire of Gazis , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976, p. 184; ISBN 0-521-29163-1 .

- ↑ Alexander Mikaberidze: Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, 2011, p. 152-153

- ^ Trpimir Macan: Povijest hrvatskog naroda , 1971, p. 207

- ^ Ferdo Šišić: Povijest Hrvata; pregled povijesti hrvatskog naroda 600 - 1918, p. 345, Zagreb ISBN 953-214-197-9

- ↑ HRVATSKE POVIJESNE BITKE - POBJEDA KOD SISKA .

- ↑ Bruno Sušanj, Zagreb - Tourist Guide, Zagreb: Masmedia Nikola Štambak, 2006, p. 22nd

- ↑ "400 years anniversary of the battle at Sisak" , bsi.si (1993); Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ Pošta Slovenije: 1993 Stamps - 400th anniversary of the Battle of Sisak , June 22, 1993; Retrieved June 22, 2014.