Battle of Lissa

| date | July 20, 1866 |

|---|---|

| place | Vis , Croatia |

| output | Austria's victory |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 28 ships | 26 ships |

| losses | |

|

2 ships |

no ship |

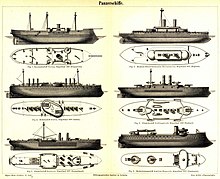

In the Third Italian War of Independence , the Imperial Austrian Navy on July 20, 1866 won by applying the Rammtaktik the naval battle of Lissa in today Croatia associated island Vis against the numerically and technically superior Italian fleet . Presumably it was the last naval battle won by using this tactic. This was also the first naval battle in which newly developed ironclads were used on a large scale .

Despite several victories over Italy, Austria lost the war on the northern front against Prussia, which was allied with the Italians ( Battle of Königgrätz ) and had to cede the province of Veneto to Italy in the Peace of Vienna .

The fleets

Austrian Empire

With the Peace Treaty of Campoformio in 1797, the provinces of Venice, Istria and Dalmatia came under Austrian rule and with them the entire Venetian fleet. Thus, since the end of the 18th century, the empire had a strong naval force in the Mediterranean. Of the 7,871 seafarers in the KK fleet, far more than 5,000 men were Venetians from the coastal areas of today's Croatia, which were then settled in Italy . Until the outbreak of World War I, it was considered the sixth largest in the world.

The equipment of the fleet was largely out of date by the time of the Battle of Lissa. Their ships were still equipped with muzzle-loading guns, while the Italians already had the most modern British-made breech-loading guns, rifled steel-hoop Armstrong guns. One still shot with solid spheres , but they were largely ineffective against the new, heavily armored ships. Therefore breech-loading guns were ordered for the fleet from the Krupp-Gussstahlfabrik . In the relevant literature one can read again and again that they were confiscated by the Prussian authorities, which is historically incorrect. Rather, the guns supplied by Krupp did not meet the expected requirements and were immediately sent back to the manufacturer. Tegetthof therefore instructed his artillery officers not to fire the classic broadside when fighting armored ships , but instead to concentrate the gunfire on a point of the enemy ship in order to permanently shake the structure of the ship's side . Five of the seven ironclad ships in the KK fleet were in the roadstead , neither overhauled nor equipped . The remaining two, the SMS Ferdinand Max and SMS Habsburg , were still in the shipyard of Trieste . The largest liner in the fleet, the SMS Kaiser , was considered totally out of date and unusable. In order to compensate for the lack of firepower, the ramming technique was also practiced and refined in the Austrian Navy. Tegethoff's flagship at Lissa, the SMS Ferdinand Max , was provided with a particularly reinforced bow that protruded forwards. Due to a lack of coal, these maneuvers often had to be practiced by the teams with smaller vehicles. In his need, Tegetthof resorted to another improvisation: he had the SMS Kaiser , as well as some frigates and corvettes , temporarily armored with railroad tracks and anchor chains on the bow and side walls before the battle of Lissa .

The Rear Admiral Wilhelm Freiherr von Tegetthoff , extremely popular with his subordinates, was considered one of the most experienced and creative naval commanders in Europe after the naval battle of Heligoland in the German-Danish War , especially when it came to compensating for the lack of combat strength of the Austrian fleet with emergency solutions. In addition, through his numerous initiatives in terms of repairing and organizing the fleet, he soon managed to spark patriotic enthusiasm and genuine fighting spirit among his men. However, the Austrian Navy had grown in its tasks over the centuries and its crews were very experienced. Their officers, in particular, enjoyed excellent training and were considered very self-confident.

Kingdom of Italy

The still young Kingdom of Italy began shortly after its foundation - from 1861 - to build up a modern naval force with the aim of driving the Austrians out of the Adriatic. The fleet was considered a prestige object in which a lot of money had been invested. The combat ships came from shipyards in Great Britain, France and the United States and were technically up to date. Their cannons fired HE shells and had a much greater range or penetration power. The speed of these ships was also higher. The Affondatore, which was launched in Great Britain in 1866 and is equipped with a nine-meter-long ram, was even considered the most powerful and unsinkable warship in the world. According to an article in the London Times, she was also able to single-handedly destroy the Austrian fleet if necessary. The heroic naming ( affondatore = sinker, terribile = terrible, formidabile = wonderful) should also emphasize their superiority. Their crews also had a good nautical reputation and were considered to be just as experienced and capable as those of their opponents. The officers in particular were well trained in the field of nautical science . The technical and numerical superiority, however, led the high command to a dangerous carelessness. The fleet commander Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano had a large-scale fleet maneuver carried out in the early summer of 1866 . On the other hand, everyday practical combat exercises, such as those carried out at the KK Marine without a break, were considered unnecessary.

prehistory

In June 1866 war broke out between Prussia and Austria . Italy, allied with Prussia in the alliance of April 8, 1866 , also declared war on Austria and allowed its troops to march into Lombardy . Although the Italian army outnumbered the Austrians, it was defeated on June 24th and forced to retreat. Since the Prussians defeated the Austrians in the Battle of Königgrätz (today: Hradec Králové ) on July 3, no political capital could be made from it. In order to provoke Italy, Austrian warships surprisingly and unhindered carried out a maneuver just two nautical miles from the Ancona naval base, which angered the Italian public especially against the commander of the Italian fleet, Admiral Carlo Conte di Persano , which now for this disgrace the final destruction of the Habsburg fleet demanded. But he preferred to wait for the affondatore to be delivered. This, the defeat of Königgrätz and the news that the Austrians had asked the Prussians for an armistice, finally forced the Italian Navy to act. On April 30, 1866, Rear Admiral Tegetthoff was therefore ordered to keep an eye out for the enemy fleet and ordered additional patrols for this purpose. On May 20 of the same year Italy finally officially declared war on Austria. The Italians wanted to take the Austrian territories on the Adriatic Sea in order to use them as a bargaining chip in the peace negotiations. Admiral Persano cruised on the latitude of Lissa from July 9th to 11th, but without attacking the Austrians. Persano's passive behavior was increasingly criticized, and the Minister of the Navy, Agostino Depretis , ordered some promising action to be finally taken. As a result, it was decided to take the island of Lissa (today: Croatian Vis ), the so-called “Gibraltar of the Adriatic” . The aim was to create a maritime base of operations in order to later be able to land Italian infantry in Dalmatia relatively safely . Subsequently, plans were made from there to fall in the rear of the Austrian Army in the South and then march on Vienna. Furthermore, the Austrian fleet was to be forced into a decisive battle and destroyed. The Italian fleet left Ancona on the afternoon of July 16 with the destination Lissa, but without having prepared a detailed operational plan.

development

Italian attack on Lissa

Persano's fleet crossed Lissa on July 17th, but was still too far away for the defenders to identify. The only one of his ships that approached the coast within sight was the reconnaissance ship RN Messaggero , which had the chief of staff of the fleet on board to scout the positions of the coastal batteries and fortresses. The next day the entire Italian fleet finally appeared before Lissa. At that time, 1,833 soldiers, stationed in some heavily armored forts and coastal batteries (Wellington, Bentainks, Magnaremi and Nadpostranje) and a total of 88 cannons, were available to defend the island . There was also a police station on the 585-meter-high hill of Hum, which was connected to the Dalmatian mainland by telegraph via the neighboring island of Lesina . The Austrian fortress commander, Colonel David Freiherr von Urs de Margina , was able to repel the first attacks by the Italians. Nevertheless, her victory was only a matter of time and Margina had to hope that the KK fleet would quickly come to his aid. Some of the Italians' ironclad ships were marched to the port of the neighboring island of Lesina in order to interrupt the telegraph connection Lissa-Lesina-Split. More ships were sent to the northwest for reconnaissance.

The majority of the Italian fleet attacked Lissa at 10:30 a.m. in three different positions. The first squadron under their commander Giovanni Vacca opened fire on the Austrian batteries near Komiža . The second squadron, under the command of Admiral Persano, attacked the port of Lissa, while the third squadron, consisting of the wooden frigates under the command of Giovanni Battista Albini, was ordered to destroy the batteries of Nadpostranje and the troops in the bay to set ashore from Rukavac . However, the coastal batteries (especially those in Komiža) were too high for the angle of fire of their guns. As a result, after a few hours of useless bombardment, the Italian ships withdrew and instead supported the second squadron in its attack on the port of Lissa.

At that time the imperial fleet was not anchored in the port of Pola, but in the Fažana Canal . This berth had the advantage that the ships could not be blocked by the enemy in the harbor basin. In order to attack the ships in the canal, the Italians would have had to split their fleet to block both exits, but would then have faced the entire Austrian fleet if they attempted to break out. On July 18, Tegetthoff received news of the Italian attack for the first time, but initially interpreted it as a diversionary maneuver to lure the Austrian fleet away from Istria and Trieste. On July 19, based on the news there was no longer any doubt that Persano intended the conquest of Lissa.

On July 19, Persano pulled together the entire Italian fleet in front of the port of Lissa and attacked again. The Italians received further support from the tower-equipped armored ship RN Affondatore and some troop transports. Although four ironclads were able to penetrate the port, it failed to break the stubborn resistance of the defenders.

Course of the battle

After the telegraph line between Lissa and Lesina had been interrupted by the Italians at the post office, the postmaster of Lesina, Bräuner, fled to the hills of Salbon with his telecommunications equipment and connected himself to the still intact line to Split. So he was able to pass on the observations of Pastor Plancic, who had correctly interpreted the events at sea, to Pola. Otherwise the alert to the Austrian fleet would have been too late.

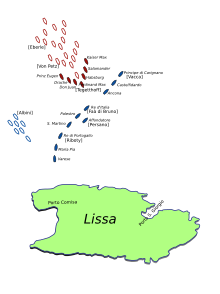

After receiving further telegrams from Lesina about the presence and activities of the Italian fleet, Tegetthoff decided to leave his safe position in the northern Adriatic with his squadre immediately in order to relieve the hard-pressed garrison on Lissa. The entire Austrian fleet, three divisions each consisting of seven combat ships, five escort ships and 7,800 crew members, left the Fažana Canal on July 19 at around 1 p.m. and headed south at full steam. The incompletely equipped tank frigates Ferdinand Max and Habsburg were also there . Even during the night Tegetthoff allowed Lissa to approach at full speed. A storm low from the west brought rain, wind and heavy swell, but in the early morning the storm subsided completely. At around 9 o'clock the silhouette of the island finally emerged from the fog, only a little later after the Italian fleet had gathered again north of Lissa for another attack.

On the third day of the siege, July 20, 1866, the position of the defenders of Lissa became increasingly critical. Two thirds of the cannons had been destroyed by the bombardment the day before and the Italians had been preparing to land their troops since early that morning. At the moment when the armored ships started the decisive attack on the port and the batteries and the wooden ships with 2,200 infantry were preparing to enter the bay of Rogačić , the lookout of the reconnaissance ship RN Esploratore spotted the Austrian fleet, which was rapidly moving north-west Direction approached. When Persano received this message, he had the landing operation aborted and brought his ships into position against the enemy fleet. His battle line-up was known to the Austrians in advance from the newspapers, since the Italian leadership, with their absolute certainty of victory, had not even ensured that their war plans were kept secret.

The Austrian fleet attacked in three wedge formations. The first attack wedge (under the orders of Admiral Tegetthoff) consisted of seven armored ships, the second (under the orders of the liner captain Commodore Anton von Petz ), about 1000 meters behind the first, consisted of seven wooden ships with screw drives, led by the two-row ship of the line SMS Kaiser , and the third wedge (under the orders of the frigate captain Ludwig Eberle), another 1000 meters behind the second, consisted of seven gunboats . A cleverly chosen line-up of the KK units, which should also contribute to their later victory. Immediately before contact with the enemy, Tegetthoff had "The enemy run to make them sink!" Another command should have followed “Must be a victory for Lissa!”. But only the signal “must” ran along the line. At 10:30 am, when the two fleets were already very close, Tegetthoff ordered the speed to be increased again and signaled "Close distances - ram the enemy" . The wooden screw frigates were supposed to support the ironclad.

The plan of the Italians was to surround the Austrian fleet and then separate the wooden ships from the ironclad. Allegedly, when Admiral Persano saw the enemy running towards his fleet, he mockingly exclaimed: "Ecco i pescatori!" (“Well, the fishermen!”), But this quote has not been historically proven. Because of the ongoing preparations for landing and the protection of the troop transports, he was only able to use ten armored ships against Tegetthoff at the beginning of the battle. The RN Formidabile , badly damaged during the attack on the port of Lissa, returned to Ancona at all , the Terribile fell behind the Komitza , and the wooden ship flotilla was still busy picking up the landing forces and their equipment.

Persano drove towards the Austrians with three armored ships in each squadron in line formation, but decided because of a rudder damage to quickly change his ship before the meeting. He disembarked the RN Re d'Italia and went to the RN Affondatore , which was supposedly safer for him , but was still outside the combat formation and fatally only had a vice admiral flag but no admiral flag. By his crossing, which lasted a quarter of an hour, he caused great confusion among his commanding officers, which soon opened a gap between the vanguard and the center of the Italian battle line-up. Tegetthoff immediately recognized his chance and broke through the enemy line at 10:50 a.m. at this point. This action was decisive for the later outcome of the battle, as the Austrians could now use their ramming tactics more quickly. It was supposed to disperse the enemy and not give him the opportunity to use his far superior artillery massively against the KK ships.

The imperial ironclad immediately turned to starboard and attacked the center of the Italian formation. The ship of the line and the wooden frigates of the second wedge threatened the Italians from aft , while the gunboats of the third wedge had to turn north again after they were in turn violently attacked by the Italian vanguard, pursued by some Italian ships. The Italian wooden frigates under the command of Captain Albini stayed out of the fight. When the 2nd division met the enemy, SMS Novara alone received 47 hits in the fire fight. Their captain, Erik af Klingt, was killed in one of them.

The battle soon broke up into individual skirmishes (so-called melee ) due to the communication made difficult by the thick coal and powder smoke . In powder smoke, often only the color of the hull made it possible to distinguish between friend and foe. So Tegetthoff gave his officers the order “When battle comes, everything that is gray rams.” The focus was still the center of the Italian line, where Tegetthoff and his seven ironclads attacked four Italians. The thick smoke caused additional confusion on the battlefield and helped him to implement his risky plan of wrestling the Italians, especially in close combat . Artillery fire was only opened on the enemy ships when the opportunity was appropriate, mostly when they emerged from the billows of smoke, sometimes at a distance of less than 50 meters.

Most of the ships involved in the fight, especially the Austrian ones, tried to give their opponent a final ramming thrust. Tegetthoff's flagship , the SMS Archduke Ferdinand Max , stood out in particular . Although from an unfavorable angle, she rammed the gunboat Palestro at the stern with such force that some of her sailors were thrown against the bow of the Ferdinand Max . Tegetthoff wanted to use this opportunity to encourage his men to do a hussar piece by asking: “Who wants to have the flag ?!” . Thereupon the Croatian officer candidate and helmsman Nikola Karkovic swung himself to the stern of the Palestro, tore the cloth and got back safely to his ship despite violent defensive fire. This flag was the most important Austrian trophy in this battle.

At the same time, the stern of the Kaiser was under heavy enemy fire from the Italian flagship RN Affondatore . The emperor's team - which the Italians mistakenly believed to be Tegethoff's flagship - was able to avoid being rammed by the affondatore twice and finally fired a well-aimed broadside at him from a short distance. Even though the cadence of the Kaiser’s cannons was much lower than that of their opponent and could not penetrate its armor, some of the projectiles still did considerable damage to the Affondatore . The ship of the line also survived the battle with the Re di Portogallo , after which the badly damaged Kaiser had to retreat to the port of Lissa.

The Re d'Italia was also under heavy fire and the Palestro tried to come to her aid. However, after it was rammed by the Ferdinand Max , it suffered numerous other hits from artillery. Fire broke out and she withdrew from the battlefield around the same time as the emperors . Two other Italian ships towed the burning Palestro , and its crew was to be evacuated from the ship in boats. However, Captain Capellini stopped the evacuation of his ship and stayed with the crew on board to fight the fire.

Meanwhile the battle reached its climax. Since the rudder of the Re d'Italia was damaged, it had to make a full stop. Tegetthoff did not escape this and at 11:30 he ordered to run at full speed (11.5 knots) towards the Re d'Italia and rammed her on her port side . The ship leaked immediately, sank over the bow in just three minutes, dragging 381 of its sailors with it.

Admiral Persano now obviously lost track of the battle because he kept sending contradicting flag signals such as: "The fleet should chase the enemy, free maneuvering, free sailing", "Every ship that is not fighting is not in its position" , “Follow your commander in line formation”. However, many of his captains disregarded the signals, as they did not know about Persano's move to the Affondatore.

At around 12:15 p.m. the hot phase of the battle was over. The Austrian ships separated again from the Italians and ran in three parallel lines to the north, towards the port of Lissa. The Italians rallied in two lines west of the Austrian position. Individual gun salvos were exchanged until 2:00 p.m. local time, after which the fire was completely stopped. Half an hour later, the Palestro exploded after fire reached its ammunition chamber. Only 19 of its original 250 crew members survived this disaster.

Neither of the two opponents tried to resume the fight in the afternoon. Still outnumbered but demoralized by the losses and without sufficient coal and ammunition, the Italians left the battlefield at sunset and retreated back to Ancona. In the certainty of their ultimate victory, the Venetian crew members of the imperial ships threw their caps in the air and shouted “Viva San Marco !”.

losses

The Italian casualties were 612 dead, 38 wounded and 19 prisoners. The Austrian fleet had 38 dead and 138 wounded. Among them are the liner captains Moll and Erik af Klint from Sweden . In the foreign press it was repeatedly alleged that the liner SMS Kaiser was sunk, but this was not true. Several ironclads on both sides were slightly damaged. The sinking of the Affondatore off Ancona - three days later - was also caused by the damage in the course of the battle. Because of the Prussian victory at Königgrätz, Austria had to cede Veneto to Italy in the Peace Treaty of Vienna (October 12, 1866). However, the victories of Custozza and Lissa prevented Austria from having to give up the coastal region (Trieste, Istria), Dalmatia and South Tyrol.

epilogue

The Austrian fleet was able to win this battle because the decisive orders were given without delay, the battle plan was well prepared and thought out and, above all, its crews were excellently trained. A significant part of the success was also made possible by Tegetthoff's determined and unconventional approach.

The Battle of Lissa was the first naval battle in European war history to use ironclad ships and influenced the development of new naval tactics in the second half of the 19th century. However, too much attention was paid to the ramming tactic in battle. Only a few ships were specially equipped for this, and only some of the ramming attempts during the battle actually had the desired success. With the development of even more powerful and long-range cannons that could sink ships while they were still approaching the enemy for ramming, this tactic soon proved to be obsolete. The Italians had more numerous and better ships than the Austrians, but could not use this to their advantage. Their brave and virtuoso fighting sailors had also been poorly led, which was also decisive for the outcome of this battle.

Consequences

The defeat was viewed by the Italians as a national tragedy. Admiral Persano was dismissed from office and dishonorably dismissed from naval service. Tegetthoff, on the other hand, was promoted to Vice Admiral by Emperor Franz Joseph for his mission - still on the battlefield, so to speak . A short time later he was also awarded the Maria Theresa Order with a command clasp. He was declared an honorary citizen in Vienna and numerous other cities of the monarchy. He also received an exuberant letter of congratulations from his former superior, who is now Emperor of Mexico, Ferdinand Maximilian . The postmaster of Lesinar, Bräuer, was also awarded a medal for his services. Pastor Plancic received a valuable monstrance donated to his church.

Commemoration

In the naval hall of the Army History Museum in Vienna, the naval battle near Lissa is documented in detail on the basis of ship models , including two of the SMS Archduke Ferdinand Max , numerous paintings, photographs and memorabilia.

In 1866, the Lissagasse in Vienna- Landstrasse (3rd district) was named after the naval battle of Lissa. A cross street of Lazarettgasse in the Gries district of Graz, the Lissagasse , is also intended to commemorate this memorable event in Austrian military history.

Every year around July 20th, a commemorative event in honor of those who died in the naval battle at the Reichsbrücke takes place in Vienna , at which high-ranking officers of the Austrian Armed Forces are always represented. On July 17, 2016, to mark the 150th anniversary of the battle, a memorial event with dignitaries, a seaman's choir and a history lecture was held in Graz's Barmherzigenkirche .

In the Museo del Risorgimento in the Italian national monument in Rome , a painting, an Austrian lifebuoy and half a rudder of the Austrian ship Laudon are shown in memory of the sea battle . However, there was a ship of this name in the Austrian Navy only from 1873.

literature

- Heinrich Friedjung: Custoza and Lissa . Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1916 ( Austrian Library No. 3)

- Agnes Husslein (Ed.): Anton Romako. Tegetthoff in the sea battle near Lissa . Catalog for the exhibition in the Austrian Gallery Belvedere , Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-901508-79-0

- Christian Ortner : The sea war in the Adriatic Sea 1866 , in: Viribus Unitis , Annual Report 2010 of the Army History Museum. Vienna 2011, pp. 100–124, ISBN 978-3-902551-19-1 ( online in the HGM knowledge blog ).

- AE Sokol: Austria's naval power. The Imperial and Royal Navy 1382–1918. F. Molden, Vienna 1972.

- AE Sokol: The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. United States Naval Institute, Annapolis 1968.

- Johannes Ziegler: The events on Lake Garda, the Italian attack on the island of Lissa and the sea battle at Lissa. In: Archives for marine life. Self-published, Vienna 1866.

- Helmut Neuhold: Austria's heroes at sea . Pp. 125-134. Styria Verlag, Vienna-Graz-Klagenfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3-222-13306-0 .

- Igor Grdina: Wilhelm von Tegetthoff and the sea battle near Lissa from July 20, 1866. Translated from the Slovenian by Urška Črne and Hubert Bergmann. Maribor: Umetniški kabinet Primož Premzl, 2016. ISBN 978-961-6055-46-8 .

- Renate Barsch-Ritter: Austria on all seas. History of the K. (below) K. Navy 1382 to 1918. Graz, Vienna, Cologne 1987.

- HH Sokol: The emperor's sea power. Almathea, Vienna 1980.

Web links

- Picture collection ( Memento from March 17, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- The Battle of Lissa on the Italian Navy website (Italian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Basch-Ritter 1987, pp. 61-62.

- ^ ORF documentary, Myth History: The Emperor's Sea Hero: Admiral Tegetthoff, 2016.

- ↑ HH Sokol 1980.

- ^ Army History Museum / Military History Institute (ed.): The Army History Museum in the Vienna Arsenal . Verlag Militaria , Vienna 2016, ISBN 978-3-902551-69-6 , p. 155.

- ↑ Archived copy ( memento of the original from August 15, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Remembrance of Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, commemorative event on the occasion of 150 years of the Battle of Lissa, City of Graz, July 18, 2016, accessed July 20, 2016. - Photo report, around 100 participants.