Simon Studion

Simon Studion (born March 6, 1543 in Urach , † between 1608 and 1610 in Maulbronn ) was a Württemberg poet, regional historian, regional archaeologist and author of religious-political writings. He is known as the “father of Württemberg antiquity” and provided the basis for the Roman lapidarium of the Württemberg State Museum . His writings are in Latin and have not been printed or translated.

His poetry has been forgotten, and his archaeological and regional historical works are only of cultural and historical value. His main and life work, the apocalyptic “Naometria” of around 2000 pages, is a work full of mystical calculations and bold prophecies, based on the interpretation of biblical quotations. The Naometria also had no major aftereffects, apart from the influence it had on the secret society of the Rosicrucians .

Life

Early years

Simon Studion was born on March 6, 1543 in Urach, the first of four sons. His father was the cook Jakob Studion, who was probably employed at the court in Urach after immigrating from Hesse. Simon Studion grew up in Urach and probably attended Latin school there and then the Herrenalb convent school . In the year Simons was born, his father got a job as a cook at the ducal court in Stuttgart. The family later also moved to Stuttgart.

Education

From 1561 to 1565, Simon Studion studied theology at the University of Tübingen on a scholarship from the Tübingen Abbey . He obtained his bachelor's degree in 1562 and completed his studies in 1565 under the classical philologist and historian Martin Crusius with a master's degree . He put the focus of his studies on mystical arithmetic , probably under the influence of the professor of ethics Samuel Heyland . "This was not only an excellent mathematician, but also enjoyed a great reputation as an astronomer and even more as an astrologer."

job

Simon Studion was denied the desired pastoral profession due to a speech impediment. From 1565 to 1572 he worked with moderate pay as a collaborator (assistant teacher) at the pedagogy in Stuttgart.

In 1572 he switched to the Latin school in Marbach am Neckar , where he filled the well-paid position of a preceptor (teacher) until 1605 . The Latin school was housed in a large building over 30 meters long on the city wall at Untere Holdergasse 4, where Simon Studion also lived with his family and took in foreign students as boarders.

The Latin school staff consisted of the Preceptor Simon Studion and two collaborators, of which he was the superior. From 1597, one of the two collaborators was Simon Studion's son Johann Stephan Studion. At the annual visitations by the church authorities, the Preceptor and his collaborators were commended for their impeccable work. Towards the mid-1580s, the positive assessment of Simon Studion's activity as a teacher was mixed with complaints about his “immodesty and drinking pleasure”. He was also accused of repeatedly starting quarrels with his immediate superior, the town pastor, and the Marbacher Vogt.

In the 1590s he repeatedly neglected his official duties, sometimes only appearing sporadically to class and leaving the work to his collaborators. In addition, the Stuttgart consistory could not endorse the theories of its “Naometria” for theological reasons. Despite all the concerns and complaints, the Duke seems to have held his protective hand over Simon Studion for a long time. Finally, in 1605, Simon Studion was dismissed. The Duke granted him a modest annuity and banished him to Maulbronn Monastery , where he spent the last years of his life in the benefactor's house.

In addition to his job, Simon Studion worked as a poet and regional historian and researched Roman antiquities in the country. In the twelve years from 1592 to 1604 he created his main and life work, the apocalyptic "Naometria".

Relationship with the court

Simon Studion had a good reputation with Duke Ludwig von Württemberg . He owed this to the wedding poem , in which he described the history of the Württemberg ruling house, and the seven Roman stone monuments that he had given the duke for the exhibition in Stuttgart.

After Ludwig's death in 1593, Duke Friedrich von Württemberg became his successor. Simon Studion was able to win him over in 1597 to initiate excavations in Benningen am Neckar . His work on the Roman stone monuments in Württemberg and the history of the Württemberg royal houses, which he published in the same year, was warmly received by the Duke. Since he had a great fondness for secret sciences and alchemy, Simon Studion also hoped for the support of the duke for his "Naometria" published in 1596. However, the Duke's initial interest, especially in the prophecies in the Naometria, soon fizzled out. Even the revised new version of the work from 1604 did not find the desired echo, neither with the duke nor with the public.

Retirement

Simon Studion's insubordination towards his Protestant church superiors, to whom the Naometria seemed largely intolerable, and the contentious behavior that he displayed at the Latin school and against his fellow citizens, led to his forced retirement in 1605 by an order from Duke Friedrich von Württemberg from 19. February 1605. Although he received a pension, he was banished to the former benefice house of the Maulbronn monastery . The year of death is not known, he probably died between 1608 and 1610 in Maulbronn.

family

Simon Studion's father Jakob Studion (1517–1589) was born in 1517 in Flechtdorf , a district of the North Hessian community of Diemelsee, the son of a farmer. In 1534 he emigrated to Württemberg and settled in Urach , where he was probably employed as a cook at the court. Jakob Studion's first marriage to a woman from Urach had three sons:

- Simon Studion, the eldest son.

- Jakob Studion (? -1629), 1594 Magister in Tübingen, 1595 provisional in Cannstatt, most recently from 1604 until his death city pastor in Rosenfeld .

- Bartholomäus Studion, from 1573 Preceptor (teacher) in Hagenau .

In 1543, the year Simons was born, his father got a job in Stuttgart as a cook at the ducal court. The family later also moved to Stuttgart and lived in their own house in the northern suburbs. Simon's mother died in 1571, and in 1572 his father married Katharina, the widow of Ambrosius Burkhard von Lauingen . The marriage resulted in a son who was employed in court service and moved to Ansbach in 1571 . After the death of her husband in 1589, Katharina married Gregorius Koch called Glaeri in Stuttgart in the same year.

Simon Studion married Anna Dieterich from Stuttgart in 1566. This marriage resulted in five children, three of whom were born in Stuttgart. The son Johann Stephan Studion (1570–1626) was employed by his father as a collaborator (assistant teacher) from 1597, and from 1605 he was successively the preceptor in Blaubeuren , Waiblingen and Cannstatt . The two youngest children were born in Marbach am Neckar.

plant

Simon Studion wrote over a dozen occasional Latin poems, some of which were considerable. As a writer, he published a work on Roman antiquities in Württemberg and the Württemberg state history as well as his main and life work, "Naometry", an apocalyptic work that, in the general doom and gloom at the turn of the century, helped people prepare for the coming end times should. All works (with the exception of the funeral strategy for Johannes Brenz) remained unprinted and are only available as manuscripts and copies. None of his works have survived the times, they are only of cultural and historical interest, especially the Naometria, which had a certain influence on the secret society of the Rosicrucians.

poetry

Between 1564 and 1583, Simon Studion wrote at least 15 festival and mourning poems in Latin, mostly in the form of distiches , including some of imposing length. Only the funeral elegy for Johannes Brenz was printed, the other poems are only available as manuscripts. They are kept in the Württemberg State Library and the Main State Archives in Stuttgart . Three poems are presented here: a funeral elegy, a wedding poem, and a mockery poem.

Funeral strategy

The mourning elegy for the Württemberg reformer Johannes Brenz , made up of 78 elegiac distiches , appeared in 1570 as an appendix to Jakob Heerbrand's funeral speech on Johannes Brenz. Walter Hagen's verdict on the poem: “The first, more or less official, recognition of his poetry came in 1570, when Jakob Heerbrand added his mourning delegation for the death of Johannes Brenz to the appendix to Oratio funebris. There it is emblazoned in the midst of many similar effusions ... It seems that this elegy is the only poem Studion has ever printed. "

Wedding poem

Simon Studion created a wedding poem for the wedding of Duke Ludwig von Württemberg . The marriage took place in 1575, but the poem was not completed until 1579 and given to the duke, who then increased Studion's salary. According to Walter Hagen, it is a “monster poem”, “a kind of epic of over ten thousand hexameters , which contains a history of the Wirtemberg rulers with a family tree.” The poem shows “in-depth historical studies by the author,” which he wrote for his historical- Archaeological work on the Württemberg ruling house and Württemberg stone monuments could continue to use.

Ridicule poem

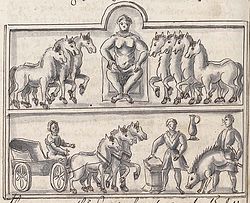

Simon Studion's mocking poem based on an Alpirsbach mockery is the interpretation of a stone image that was present in the monastery church in Alpirsbach at the time of Simon Studion and depicted a caricature of papacy and monasticism (according to Simon Studion, “a picture that depicts the divine service of the Roman pontiff ").

Antiquity and regional history

See also: Vera origo, stone monuments .

In the age of humanism in the 16th century, the exploration of antiquity experienced a new heyday. After a copy of the Germania of Tacitus was discovered in 1455 , the Germanic past of the Germans also became an object of investigation.

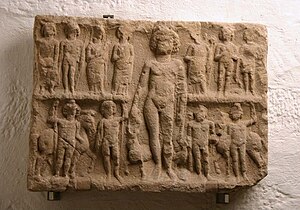

In this intellectual climate, in 1579 the historically interested Simon Studion, who had been employed at the Latin school in Marbach since 1572, found a Roman altar in the neighboring town of Benningen am Neckar . Gradually he collected more finds from Roman times in Marbach and the surrounding area and in 1583 sent seven sculptures and inscription stones as a donation for Duke Ludwig von Württemberg to Stuttgart, who had them installed in his pleasure garden and from 1593 in the newly built New Lusthaus . These stone monuments became the basis of the Roman lapidarium in the Württemberg State Museum .

In 1597 Simon Studion was able to win Duke Friedrich von Württemberg to have the first scheduled archaeological excavations carried out in Württemberg in Benningen . The remains of a Roman fort were discovered.

In the same year, Simon Studion published under the title "Vera origo illustrissimae et antiquissimae domus Wirtenbergicae" two manuscripts with identical content on Roman antiquities in Württemberg and the history of the Württemberg region. The first part of both manuscripts contains detailed explanations of the illustrations of the Roman antiquities collected by Studion and others. In the second part follows a story of the princely families who once lived in the state and the House of Württemberg. The second version of the work differs from the first mainly in a more extensive dedication and a restriction in the listing of the family members of the Württemberg dynasty.

According to the Württemberg historian Karl Pfaff , Simon Studion is not lacking in historical criticism, he attaches great importance to documents and inscriptions, but is often misguided by his predilection for speculative assumptions. The librarian and historian Wilhelm Heyd judges: “Only from this archaeological perspective does our code still have some value”.

|

|

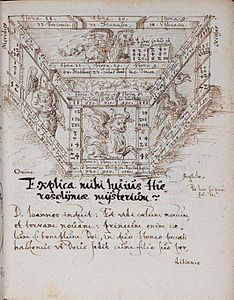

Naometry

Simon Studion's main and life work was created in the general doom and gloom around the year 1600. The apocalyptic work was intended to help people prepare for the coming end times. In 1596, after four years of work, Simon Studion completed the "Naometria", of which he presented a completely revised version in 1604 with the "Naometria Nova" (New Naometry). Both versions appeared in manuscript and were not printed, but were circulated in copies. In addition, Studio's occult work was difficult to access because massive calculations and a “jumble of the most adventurous prophecies” overgrown the work. "You feel like you are in a labyrinth from which you can see no way out."

The term Naometria means temple mass art and refers to a passage in the 11th chapter of the Revelation of John . Another passage in the book of Ezekiel , chapter 9, the author referred to himself and believed that he was (figuratively) the man who was to walk through the holy city and make the sign of the cross on the foreheads of all the men who came from him divine judgment should be spared.

In the book he announced to the reader that "he would try to explain all the secrets of the Holy Scriptures, especially with Ezekiel , Daniel and the Apocalypse , in a wonderful way by numbers". The author further claimed that he was able, through the grace of the Holy Spirit, to give an introduction to the knowledge of the sacred mysteries, combined with an exploration of the course of all times in the Church of God and its condition.

As a “prophet” he felt himself entitled to make the most daring prophecies because of his numerical speculations. In one of his predictions he claimed that Pope Clemens VIII would be the last to ascend the throne of Peter and would be crucified in 1613 with the help of Duke Friedrich von Württemberg , but Pope Clemens died of natural causes as early as 1605. Simon Studion also announced the coming of the millennium in 1621.

In his Magnum opus, Studion referred to Joachim von Fiore , a 12th century abbot, and his apocalyptic ideas. He himself influenced the later Rosicrucian movement, for example Johann Valentin Andreä and Tobias Hess . Walter Hagen judges the effect of Simon Studion's naometry:

- “His archaeological achievements have earned him lasting recognition. In contrast, the Latin poet and. the historian Studion was rightly forgotten. In a certain sense this is also true of the apocalyptic and chiliast ; but it must not be overlooked that a good part of the thoughts that he absorbed and processed by Joachim von Fiore and Paracelsus were passed on through him via Johann Valentin Andreä and his circle of friends ... The apocalyptic has finally overgrowed everything for him, including that, what he once wanted to proclaim in the general doom and gloom as a way out and salvation. "

|

|

List of works

poetry

- Simon Studion: [poem on an Alpirsbach mock picture], without place and date, handwriting, folio, 13.5 pages, poem in Latin distiches , supplement: pencil drawing “Anno dom. 1481 renovata est haec structura “[This stone statue was renewed in 1481]. Original: Württemberg State Library, copy: Registry in Alpirsbach.

- Simon Studion: Elegia. In: Jakob Heerbrand : Oratio funebris De Vita Et Morte… Ioannis Brentii… Accesserunt epicedia quaedam virorum doctissimorum. [Funeral sermon on life and death ... by Johannes Brenz ... With some mourning poems by highly learned men.] Tübingen 1570, Quarto, pages 104-109, online .

- Simon Studion: Carmen in nuptias… Ludovici ducis Wirtenbergici… et Dorotheae Ursulae filiae Caroli marchionis Badensis… [poem for the wedding… of Duke Ludwig von Württemberg… and Dorothea Ursula, daughter of Margrave Karl von Baden…]. Marbach am Neckar 1575, manuscript, quarto, 175 sheets, Württemberg State Library, call number: Cod.poet.fol.45.

Antiquity and regional history

- Simon Studion: Vera origo illustrissimae et antiquissimae domus Wirtenbergicae… Cum venerandae antiquitatis Romanis in agro Wirtenbergico conquisitis et explicatis monumentis: industria et labore M. Simonis Studione praeceptoris apud Martisbachenses. [Real origin of the noble and venerable house of Württemberg ... In addition to a treatise on venerable Roman monuments found on Württemberg soil, carefully and carefully selected and explained by Magister Simon Studion, Preceptor in Marbach.] [Marbach am Neckar] 1597, manuscript , Folio, 196 sheets, Württemberg State Library, call number: Cod.hist.fol.57, online . - With the dedication date September 1, 1597.

- Simon Studion: Ratio nominis et originis antiquissimae atque illustrissimae domus Wirtenbergicae fideliter inquisita anno nostre salutis 1597, authore Simone Studione Uracaeo apud Marpachenses praeceptore. [Faithful investigation and justification of the name and origin of the venerable and illustrious House of Württemberg, in the year of salvation 1597, by Simon Studion from Urach, Preceptor in Marbach.] [Marbach am Neckar] 1597, manuscript, 224 sheets, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, signature: Cod.hist.fol.137. - With the dedication date December 21, 1597.

Naometry

- Simon Studion: Naometria seu Introductio ad Mysteriorum sacrorum cognitionem. [Naometry or introduction to the knowledge of the sacred secrets.] [Marbach am Neckar, around 1596], manuscript, folio, 951 pages, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, call number: Cod.theol.et.phil.fol.34, online .

New naometry

-

Simon Studion: Naometria… In cruciferae MILITIAE Evangelicae gratiam. Authore Simone Studione, inter Scorpiones. Pars Prior. Intercollocutores Nathanaël Cleophas. Anno 1604. [Naometry… Dedicated to the Crucifera Militia Evangelica. From Simon Studion, among Scorpions. First part. Interlocutor: Nathanaël, Cleophas. In the year 1604.] [Marbach am Neckar] 1604, manuscript, quarto, 205, 877 pages, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, call number: Cod.theol.et.phil.qt.23, a, online .

- Illustrissimi Principi ac Domino, Domnino Friderico Duci Wirtembertgico… [Dedication to Duke Friedrich I of Württemberg].

- Corollarium Naometricum de Friderico secundo, Romanorum imperatore… [treatise on Emperor Frederick II].

- Naometriae novae et prognostici pars prior. Authore Simone Studione, inter Scorpiones. Anno 1604. Intercollocutores Nathanaël Cleophas. [New Naometry and Prophecies, Part 1, ...].

- Simon Studion: Naometriae novae et prognostici pars posterior. In cruciferae MILITIAE Evangelicae gratiam. Authore Simone Studione, inter Scorpiones. Anno 1604. Authore Simone Studione, inter Scorpiones. Intercollocutores Nathanaël Cleophas. Anno 1604. [New Naometry and Prophecies, Part 2, ...]. [Marbach am Neckar] 1604, manuscript, quarto, pages 878–1936, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, call number: Cod.theol.et.phil.qt.23, b, online .

reception

Simon Studion's impact on his contemporaries was limited as his works were not printed and only circulated as transcripts. The claim of some authors that he had a significant influence on the development of the secret society of the Rosicrucians is not supported by evidence. Only two monographic essays deal with his life and work:

- “Magister Simon Studion. Latin poet, historian, archaeologist and apocalyptic ”by the Benninger pastor Walter Hagen from 1957, and

- "The Marbach Latin school teacher Simon Studion (1543-16?) And the beginnings of Württemberg archeology" by Ludwigsburg grammar school teacher Eberhard Kulf from 1988.

In 1957, Walter Hagen made a very critical, but also understanding judgment of Simon Studion:

- “Studion has never been completely forgotten in his home country, yes, the Württemberg archaeologists revere in him the“ real father of Roman antiquity and care ”... Others saw him only as an adventurous man, an enthusiast and a crossheaded. After all, it was recognized early on that he was a man of extensive knowledge who could claim some merit for himself. "

- “It must be said, however, that Studion's historical endeavors were not primarily concerned with the study of history as such, as serious as he was about it. Rather, he amassed the extensive historical material in order to be able to use it for his main work and to base decisive theses and prophecies on it. "

- “But how difficult it was Studion made it for his contemporaries, and especially for us today, to see these positively intended thoughts of salvation and salvation in his work at all! They are almost completely covered by a jumble of the most adventurous prophecies ... "

- “His archaeological achievements have earned him lasting recognition. In contrast, the Latin poet and. the historian Studion was rightly forgotten. In a certain sense this is also true of the apocalyptic and chiliast; but it must not be overlooked that a good part of the thoughts that he absorbed and processed by Joachim von Fiore and Paracelsus were passed on through him via Johann Valentin Andreä and his circle of friends ... The apocalyptic has finally overgrowed everything for him, including that, what he once wanted to proclaim in the general doom and gloom as a way out and salvation. "

30 years later, in 1988, Eberhard Kulf gave a similar judgment on Simon Studion's life and work:

- “Studion is the product of the Renaissance, Reformation and Humanism. He saw himself as a humanist. ... His knowledge, which is by no means contemptible, gives him the rank of scholar. He supports the growing and sometimes already excessive national feeling of his time and tries to give it justification and confirmation. The contempt and hatred of papal Rome connects him with many greats of his time. Even in his quarrelsome and dogmaticness one could compare him with some humanist colleagues and not even the average. But with anything comparable, we must not overlook the fact that his field of activity is narrower. Thematically, his work revolves in tight circles around the history of the House of Württemberg; Even what seems to go further turns out to be closely linked in terms of content on closer inspection. Roman history is also at the service of German and Württemberg history for him. We notice a specialization and narrowing of the field of vision and miss the great breath of the humanists from the first half of the century. Without a doubt, Studion belongs to the 'Kärrner' generation, but who often have the self-confidence of kings. Studion was certainly not your average talent. The tragedy of his life was probably the breakdown of his career and thus the narrowing into everyday school life in the city of Marbach, whose residents had so little understanding for him. ... The low success of his work, which with one exception were not even printed, has probably driven him on the path of opinionatedness and argument. The awareness of his mission, which hardly anyone around him took seriously, made him inaccessible and also haughty; This arrogance certainly found nourishment in the long benevolence of the duke. Studion regarded his prophecies as his main merit - time has passed; perhaps he witnessed the refutation. His archaeological work seems to have been less important to him - but it is precisely these that are the reason why he is still mentioned today. "

Digression

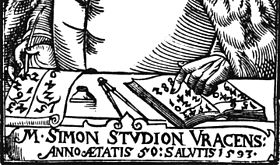

Number mysticism

According to the prophet Ezekiel's prophecy, before the coming divine judgment is held, God will choose a man who would save the strict men from destruction. According to his calculations, Simon Studion believed that this chosen one must have been born in 1543, and "this year he was born in Urach, he who was repeatedly haunted by visions and at the same time was able to reveal the future with the most sober calculations". Studion's year of birth therefore plays an important role in his numerical speculations.

The woodcut with Simon Studion's portrait (see cover picture and excerpt on the right), which was certainly made under his guidance, shows two breakdowns of numbers on the desk for his year of birth 1543:

- On the scroll (left) the numbers 15 and 43, the two halves of the year, are shown as sums: the number 15 is the sum of 2 + 4 + 9, and the number 43 is the sum of 6 + 12 + 25.

- In the open book (right) the number 1543 is shown as the sum of 220 + 441 + 882. The terms of this ingenious number series are formed according to the formula 2 n × 220 + n for n = 0, 1, 2.

These tricky, trivial dissections are intended to point to Simon Studion's life's work, the Naometria.

etymology

Just as Simon Studion liked to juggle numbers and especially years, he also loved the speculative derivation of names. In his opinion, the place name of Benningen was derived from the name of the goddess Venus (probably because of the similarity of Benn- and Ven-). A stone monument from the Marbach area, on which the name Venus appeared, should serve as evidence. Today it is assumed that the place name could go back to an Alemannic clan leader Bunno from the 3rd century. In the first documentary mention in 779 the place was called Bunninga.

Studion considered the name of Benningen's neighboring town Marbach , based on earlier interpretations, to be a combination of the name of the god of war Mars (genitive: Mart-is) and the god of wine Bacchus , according to which the residents of Marbach were (in Latinized form) "Mart-bach- enses ". A relief of the twelve gods that Studion had found in Marbach should support his thesis, because in his opinion it was consecrated to Bacchus. In fact, Bacchus is not shown in the middle of the relief, but the god Mercury, whose typical attributes he bears, for example the snake staff. Studion suppressed these attributes in his drawing of the relief. It is unclear what drove him to this fake.

At least he had further proof up his sleeve: He found that the Marbachers had "elegantly expressed" the origin of their city name in the Wilder Mann, the shield bearer of the Marbach coat of arms. Studion recognized him as a hybrid of Mars and Bacchus, equipped with the club of the god of war and the vines of the god of wine. Today it is assumed that the place name Marbach goes back to the name Markbach for Grenzbach.

Studion's etymological deductions seem to us today as adventurous and curious, after all, he at least tried to back up his claims with evidence. Studion's speculations were by no means unusual for his time. Eberhard Kulf quotes “an almost unbelievable example, which is not atypical”: Martin Crusius , who studied with Studion in Tübingen, constructed “from three abbreviations of an inscription LEG., ANT., STAT., Which in the original are separated by further words are separated ... the ancient origin of the name Cannstatt ”.

Count Ulrich's bedchamber

Simon Studion's work "Vera origo" on archaeological Württembergica and the history of the Württemberg ruling house also contains a brief biography of Count Ulrich V , the "much-loved". It begins with a description of the count's bedroom in Marbach Castle, which was destroyed in the town fire in 1693.

Copies of four wall paintings characterize Ulrich as a god-fearing man and a passionate hunter. In a twelve-line block of inscriptions, the content of which is reproduced by Simon Studion, Ulrich laments the unfortunate outcome of the Palatinate War and affirms his honorable intentions which “forced” him into this war.

The outside of the bedroom door had the humorous saying “This room is called the Paradeis. My lord, who sleeps, yawns softly '”. Another saying on the inside of the door shows that Ulrich was a head of his own: "Whoever gives this life for eternal life, he has cheated himself and is making a rainbow", a saying that is usually (and politically correct) accurate opposite read.

A detailed description of the wall paintings and inscriptions can be found in the inscription book of the Ludwigsburg district.

|

|

1. Count Ulrich in armor prays kneeling in front of a crucifixion group. 2. Count Ulrich with an inserted lance and a pack of dogs on the bear hunt. |

Studionstrasse

The Studionstraße in Benningen is named after Simon Studion. The 230 meter long street begins in the northwest at the railway underpass on Ludwigsburger Strasse and ends in the southeast at the northwest corner of the former fort. The street leads past the town hall, where some replicas of Studion's finds are displayed.

In the area around Studionstraße there are also some streets that owe their names to the ancient Romans: Am Römergraben, Römerstraße, Kastellstraße, Koortenweg, Terminusstraße, Marsstraße and Merkurstraße.

In Roman times a road ran from Cannstatt to Benningen over the dead straight Ludwigsburger Strasse (with the Roman roundabout), further over the Römerstrasse, past the southeast facade of the town hall and then along the street Am Römergraben. It led to the road to Walheim, which ran from the fort across the current cemetery. The stretch of street at the town hall was reconstructed over a length of six meters.

Terminusstrasse is reminiscent of a find by Simon Studion, an altar for the patron goddesses of the parade ground ("Campestres"), which a farmer had found while plowing in the area of the fort ("Auf der Bürg"). Studion interpreted the word "terminus" in the inscription on the altar as the Latin word for boundary stone. The classical scholar August Friedrich Pauly, born in Benningen (Paulystraße is named after him), found out more than two centuries later that it was the name of the founder Publius Quintius Terminus.

literature

life and work

Newer literature

- Juliane Fuchs; Veronika Marschall: Tübingen epices on the death of the reformer Johannes Brenz (1570). Frankfurt am Main 1999, pages 149–156.

- Albrecht Gühring: History of the city of Marbach am Neckar, Volume 1: Until 1871. Ubstadt-Weiher 2002, especially pages 52–53, 153-154, 251, 269, 280-282.

- Walter Hagen: Magister Simon Studion. Latin poet, historian, archaeologist and apocalyptist. In: Schwäbische Lebensbilder , Volume 6, 1957, pages 86-100. - With literature list.

- Eberhard Kulf: The Marbach Latin school teacher Simon Studion (1543-16?) And the beginnings of Württemberg archeology. In: Ludwigsburger Geschichtsblätter , year 42, 1988, pages 45–68.

- Thomas Schulz: The former Latin schools in the Ludwigsburg district: their history up to the beginning of the 19th century. Ludwigsburg 1995, pages 167-170, 244.

- Joachim Telle : Studion, Simon. In: Walther Killy (founder), Wilhelm Kühlmann (editor): Killy Literature Lexicon: Authors and Works of the German-Speaking Cultural Area, Volume 11: Si – Vi. Berlin 2011, pages 370–371, online . - With literature list.

Older literature

- Ludwig Fischlin: Memoria Theologorum Wirtembergensium, Volume 3: Supplementa. Ulm 1710, pages 204-208, online .

- Christian Gottlieb Jöcher : Allgemeine Gelehrten-Lexicon, Volume 4. Leipzig 1751, Column 904, online .

plant

- Johanne Autenrieth: The manuscripts of the Württembergische Landesbibliothek Stuttgart. Row 2, Volume 3. Codices iuridici et politici (HB VI 1 - 139). Fathers (HB VII 1 - 71). Wiesbaden 1963, page 39, online .

- Martin Brecht: Chiliasm in Württemberg in the 17th century. In: Pietismus und Neuzeit , year 14, 1988, pages 25–49, here 30-32. - Tobias Hess as a supporter of Simon Studion and his Naometria.

- Reinhard Breymayer : The "royal instrument". A religiously motivated metrological utopia with Andreas Luppius (1686), its roots with the early rose cruiser Simon Studion (1596) and its aftermath with the theosophist Friedrich Christoph Oetinger (1776). With the neglected fragment of a letter from Johannes Kepler . In: Martin Kintzinger (editor): Perceiving the other. Contributions to European history. Dedicated to August Nitschke on the occasion of his 65th birthday. Cologne 1991, pages 509-532, here 529-531.

- Wilhelm Heyd : The historical manuscripts of the royal public library in Stuttgart, 1. The manuscripts in folio. Stuttgart 1891, number 57, 137, online .

- Michael Klein: The manuscripts of the J 1 collection in the main state archive in Stuttgart. Wiesbaden 1980, especially pages 73-74, online .

- Karl Pfaff : The sources of the older Wirtemberg history and the oldest period of Wirtemberg historiography. Stuttgart 1831, pages 31-32, online . - About #Studion 1597.1 .

- Theodor Schmid: A literary find from the Alpirsbach monastery [ridiculous poem on Pope and monasticism by Simon Studion]. In: Blätter für Wuerttemberg Church History , year 18, 1914, pages 85–94, online . - With a translation of the poem.

- Anneliese Seeliger-Zeiss; Hans Ulrich Schäfer: The German inscriptions. 25: Heidelberg series; 9. The inscriptions of the Ludwigsburg district. Wiesbaden 1986, number 99, panel XVII, online .

Antiquity

- Rainer Braun: Early research on the Upper German Limes in Baden-Württemberg. Württembergisches Landesmuseum, Stuttgart 1991, pages 15-16.

- Philipp Filtzinger : Hic saxa loquuntur: Roman stone monuments in the Lapidarium Stiftsfruchtkasten and in the exhibition "The Romans in Württemberg" in the Old Castle = This is where the stones talk. Aalen 1980.

- Ferdinand Haug ; Gustav Sixt : The Roman inscriptions and images of Württemberg. On behalf of the Württemberg History and Antiquity Association. Stuttgart 1900, pages VIII-IX, XII, numbers 107, 112, 165, 211, 242, 249, 251, 252, 300, 320, 322-324, 326, 327, 331, 335, 337, 403, 404, 504 , online .

- Michael Nick: "Prove how far the Romans are in power ..." 500 years of Roman research in Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart 2004, pages 18-20.

- Simon Studion and the beginnings of the Roman lapidary. In: Nina Willburger; Christiane Herb: The Roman Lapidarium as an extracurricular place of learning, Landesmuseum Württemberg , pages 3–4, 40 numbers 8–9, online .

Archives

-

Main State Archives Stuttgart .

- J 1 No. 1: #Studion 1597.1 #Studion 1579 , occasional poems.

- J 1 No. 1a: #Studion 1597.1 .

Web links

- Rosicrucian page with a biography of Simon Studion

Footnotes

- ↑ Since Simon Studion's work is difficult to classify, various authors have assigned him a whole series of other epithets: archaeologists, hobby archaeologists, local history researchers, Latin teachers, apocalyptists, chiliast , esotericists, early Rosicrucians, mystics, humanists, renaissance humanists, pansophists , prophets, theologians .

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 86.

- ↑ Exception: funeral strategy for Johannes Brenz.

- ↑ For the wedding of Jacobus Mercator on February 7, 1564, Simon Studion wrote a poem in which he describes himself as "a former student". Jacobus Mercator acquired his master's degree at the University of Tübingen on February 1, 1559 and was employed as the 2nd Preceptor in the Herrenalb Monastery on February 9, 1560 and as a Preceptor in Stuttgart on May 20, 1564. As a result, Simon Studion was a student at Herrenalb Abbey on August 1, 1561 before he enrolled at the University of Tübingen. See: Genealogy Johann Ernst Kaufmann , page 15, wedding poem for Jakob Mercator .

- ↑ #Hagen 1957 , page 86-87.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , pp. 87-88.

- ^ The pedagogy was a forerunner of the Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium .

- ↑ #Kulf 1988 , page 50, # Hagen 1957 , page 88, # Gühring 2002 , page 280-282.

- ↑ In a wedding poem in 1584, Simon Studion referred to himself as " Pädagogarch in Marbach" (Rector), a somewhat grandiose name for the head of a three-person teaching staff. See: Wedding poem for Melchior hunters .

- ↑ In the title of his “Naometria”, Simon Studion is targeting pastor and Vogt in particular when he claims that he lives among scorpions in Marbach.

- ↑ # Schulz 1995 , pp. 167-170.

- ↑ #Studion 1597.1 , #Studion 1597.2 .

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , pp. 97-99. - According to research by the Marbach city archivist Albrecht Gühring, Simon Studion was still alive in 1608, while his wife is described as a widow in an official note in 1610 ( Elke Evert about Simon Studion ( Memento of the original from July 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: Der Archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note. ).

- ↑ #Studion 1604.2 , pages 1170-1171, # Hagen 1957 , pages 86-88, # Schulz 1995 , page 244.

- ↑ # Klein 1980 , pp. 73-74.

- ↑ #Studion 1570 .

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , pp. 88-89.

- ↑ #Studion 1579 .

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 89.

- ↑ #Studion 1597.1 .

- ^ # Studion-Alpirsbach , #Schmid 1914 , page 87.

- ↑ #Kulf 1988 , page 47, 52-54.

- ↑ #Studion 1597 , page 75v-82r.

- ↑ #Studion 1597.1 and #Studion 1597.2 .

- ↑ #Studion 1597.2 .

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , pp. 90-92, # Heyd 1891.1 , number 57, 137.

- ↑ #Pfaff 1831 .

- ↑ # Heyd 1891.1 , number 57. - Codex: Handwriting “Vera origo”.

- ↑ #Studion 1596 .

- ↑ #Studion 1604.1 and #Studion 1604.2 .

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 93.

- ↑ For the text see, for example: Luther Bible 1912 .

- ↑ For the text see, for example: Luther Bible 1912 .

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 96.

- ↑ From the Latin: #Fischlin 1710 , page 205th

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 92.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 94, 96-97.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 93.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 99.

- ↑ #Schmid 1914 .

- ↑ #Fuchs 1999 , pp. 152–156.

- ↑ #Autenrieth 1963 , page 39, # Klein 1980 , page 73.

- ↑ # Heyd 1891.1 , number 57.

- ↑ # Heyd 1891.1 , number 137.

- ↑ Crucifera Militia Evangelica: perhaps the name of an existing or to be founded order, literally: "Army of those marked with the cross of the Gospel".

- ↑ Studion calls his Marbach opponents scorpions.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 86.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 92.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 94.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 99.

- ↑ #Kulf 1988 , pp. 66-67.

- ↑ # Hagen 1957 , page 96.

- ↑ There may be mystical meanings hidden behind the individual terms of the sums.

- ↑ #Kulf 1988 , page 58.

- ↑ # Gühring 2002 , pp. 52–53.

- ↑ #Studion 1597 , pages 31–34, museum-digital .

- ↑ # Gühring 2002 , pp. 52–55.

- ↑ #Kulf 1988 , page 58, #Studion 1597 , page 26.

- ↑ #Kulf 1988 , page 54.

- ↑ #Studion 1597.1 , 153r-155r.

- ↑ #Studion 1597.1 , 151r-153r.

- ↑ # Seeliger-Zeis 1986 , number 99, # Gühring 2002 , pages 153-154.

- ↑ # Seeliger-Zeis 1986 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Studion, Simon |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German poet, historian, archaeologist and apocalyptist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 6, 1543 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Bad Urach |

| DATE OF DEATH | between 1608 and 1610 |

| Place of death | Maulbronn |