Stosch stone

The Stochsch's stone is an Etruscan scarab from the early 5th century BC. It is a gemstone made of carnelian , on which five heroes are depicted with name inscriptions from the legend of the seven against Thebes . The gemstone comes from the collection of the archaeologist Philipp von Stosch and is now in the antiquities collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin . It is one of the most important works of art in Etruscan glyptics .

description

The gem is made of carnelian, a mostly opaque orange variety of chalcedony . The stone is elliptical in shape and has a length of 1.6 cm and a width of 1.2 cm. Its thickness varies between 0.2 and 0.5 cm. A group of people is cut into the carnelian. The image field is surrounded by a decorative border.

Pictured are five partially armed warriors, three of whom are sitting on stools in the foreground and two are in the background. The two standing warriors each wear a spear , a shield , a breastplate and a helmet with a crest . The middle of the seated figures is holding a spear, the other two are depicted without weapons or protective clothing . The middle seated person is apparently wrapped in animal skin that covers the arms but not the shoulders. The second seated person is wearing a cloak and has bared one shoulder. Both keep one knee bent. The third seated person is completely wrapped in a cloak and holds one knee with both hands, which is thereby lifted slightly.

The depicted are divided into a group of three and two by two vertical lances. This group formation is canceled again, as new groups of three and two result from the heads leaning towards each other. Four of the five people seem pensive, three of them keep their heads down. Only a warrior shows a certain degree of activity by turning away from the head-tilted group of three and grabbing the lance and swinging the shield as if ready to leave.

The figures are not cut deeply into the stone like a gem , but rather the background of the picture motif was cut away so that the figures protrude from the stone like a relief . Gemstones made in this way are known as cameos . Since gems are also used as a generic term for all cut gemstones and gemstones, gemstones like these can also be referred to as gems. Such gems were also used as sealing stones in ancient times . These often had the shape of beetle-shaped ring stones, which are therefore also known as scarabs . Scarabs of this species have been around since the late 6th century BC. Made from carnelian by Etruscan stone cutters and often decorated with images from the Greek myth . This type of signet ring , which is widespread in Etruria, seems to have been a genuinely Etruscan achievement that later found widespread use throughout central Italy.

The style of the representation clearly shows Etruscan peculiarities. These include the large heads in relation to the body and the design of the sometimes archaic long, striped hair. The naming of the figures by inscriptions is also an Etruscan peculiarity that can also be found on Attic vases, but not on Greek gems. On the other hand, owner names or signatures, in contrast to Greek glyptics, do not appear.

In the 18th century the beetle was cut off and the remaining gem was set as a ring.

Inscriptions

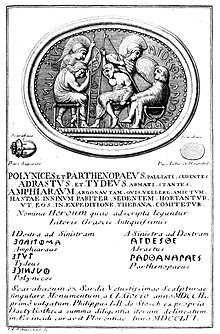

The inscriptions show that five heroes from the legend of the seven against Thebes are depicted on the scarab . Two of the inscriptions are written in mirror-inverted letters from right to left , in accordance with Etruscan writing habits . The other three follow the writing direction from left to right without mirroring the letters. However, if you press the seal into a soft material such as clay , a mirror-inverted imprint is created with two inscriptions in the usual writing direction and three mirror-inverted according to the Etruscan writing habits. Most of the engravings from the 18th century depicted the imprint of the seal.

- Inscriptions from left to right: PARTHANAPAES ( Parthenopaios ), ATRESTHE ( Adrastos )

- Inscriptions from right to left: AMPHIARE ( Amphiaraos ), TUTE ( Tydeus ), PHULNIKE ( Polyneikes )

The tragedy of the Seven against Thebes is the last part of the Oedipus - trilogy of Greek playwright Aeschylus tells the battle of the brothers Eteocles and Polynices for power in Thebes . Polynices attacks Thebes and his allies, including Hippomedon and Capaneus , who are not shown on the scarab. Both brothers perish in battle. In the same way, all attackers except Adrastos lose their lives. The seer Amphiaraos foresaw this end.

interpretation

The Etruscans adopted Greek myths and often developed new scenic representations in the visual arts . Here the seer Amphiaraos sits in the middle of the allies, to the left and right of him Parthenopaios and Polynices, behind him standing Adrastus and Tydeus. Two heroes are missing for no apparent reason. Those present are apparently depressed because Amphiaraos prophesied their fate. Only Adrastos is ready to leave. He will eventually lead the heroes to battle and be the only one to return home. No comparable scenery is known in Greek art for this representation . It is conceivable that the Etruscan stone cutters used templates on Attic vases , as could be deduced for Etruscan bronze mirrors.

In the Greek legend, Amphiaraos refused to take part in the war campaign because of his vision and thus frightened everyone else. With the help of the Eriphyle , the wife of Amphiaraos, Amphiaraos could still be persuaded to take part in the war and fate took its course. Perhaps the ring was intended to warn and protect the wearer of disastrous family disputes.

The legend of the seven against Thebes was just as popular with the Etruscans as the legend of the Trojan War , as seers appear in both stories with Amphiaraos and Teiresias . The proclamation of divine messages ( prophecy ) and the interpretation of the signs of the gods ( divination ) played an important role in the Etruscan religion .

Provenance

The scarab was created between 500 and 480 BC. And later found in Perugia , which was located in ancient Etruria and is now the capital of the Umbria region . The gem came into the possession of Conte Vincenzio Ansidei, who was a collector of antiquities and exhibited his pieces in his own museum. Ansidei was a member of the Accademia Etrusca , founded in 1726 , a learned society for the study of the culture of the Etruscans, which still exists today and has its seat in Cortona . Baron Philipp von Stosch (1691–1757), who was living in Italy at the time, was one of the most important collectors of antiquities of the 18th century and by the middle of the century had put together the largest collection of gems of his time. To thank him and to supplement his collection, Ansidei bequeathed him the Etruscan scarab in the name of the Accademia Etrusca in 1755. Another valuable gemstone was in the Stosch collection: the Etruscan scarab with Tydeus . After the Baron's death in 1757, his adopted nephew Heinrich Wilhelm Muzel inherited the collection and sold it in full to King Friedrich II in 1764. The collection later became one of the foundations of the Berlin Collection of Antiquities . The scarab is now in the Altes Museum on Berlin's Museum Island .

Art history background

Antonio Francesco Gori (1691–1757), an Italian archaeologist who has made a particular contribution to the study of Etruscan art , received permission from Conte Vincenzio Ansidei in 1742 to inspect the Etruscan scarab with the seven against Thebes in his museum in Perugia to take and make a drawing. In 1749 he published the volume Storia antiquaria etrusca , in which he also dealt with the Etruscan scarab and presented a wood engraving as an illustration . Since he also dealt with the Etruscan script, he was able to decipher the inscriptions almost perfectly and correctly assign them to the Greek models.

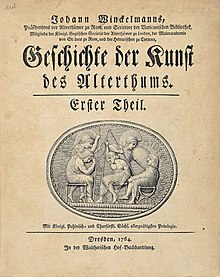

After Philipp von Stosch received the scarab in 1755, he commissioned Johann Adam Schweickart (1722–1787) to draw the gems in his collection and to make copperplate engravings . Among the artifacts shown was the scarab, the illustration of which quickly spread and was highly valued for its quality. Von Stosch finally also planned the publication of his gem collection and wanted to win over the art writer and antiquarian Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717–1768) for the publication. After his death, his heir Heinrich Wilhelm Muzel implemented the project. Between 1758 and 1759 Winckelmann scientifically evaluated the collection of antiques and published his results in Florence in 1760 under the title Description des pierres gravées de feu Baron de Stosch .

In this gem catalog Winckelmann provided the first apt descriptions of Etruscan works of art, which can hardly be surpassed in terms of esteem. In the descriptions of the Etruscan gems one finds first considerations on the Etruscan style of the figures, on the proportion and composition. Winckelmann also came to the modern realization that the archaic stone cutters had great care and finesse and had already perfected their artistic technique. Winckelmann went into detail about the Etruscan scarab under catalog number 172 and recognized it as an important work of art from the early Etruscan period. He also mentioned Gori's short treatise and regretted the poor quality of the wood engraving, which was apparently unsuitable for the delicacy of the subject.

The work on the gem collection became a preparatory work for Winckelmann's main work History of Ancient Art from 1764. The title page shows the copper engraving of Stosch's stone by Johann Adam Schweickart as the title vignette . Winckelmann distinguished three art styles among the Etruscans, an archaic, a subsequent and a last, which had improved under the influence of Greek art. He believed that he could delimit the art style that followed archaicism by means of mannered-looking stylistic features that he had recognized on the gems in Stosch's collection.

In his late work Monumenti antichi inediti from 1767, Winckelmann again dealt in detail with the problem of the dependence of Etruscan art on Greek art and revised some positions. More clearly than in the history of ancient art , he emphasized the independence of the Etruscan style and now found that the Greek influence had significantly changed Etruscan art, but not improved it. Not least because of his in-depth investigations into the gems, Winckelmann, contrary to the prevailing view at the time, moved the heyday of Etruscan art to the 6th and early 5th centuries BC. The copper engraving by Schweickart is also shown in this work and reflects the outstanding importance of this gem for the appreciation of Etruscan art.

literature

- Peter Zazoff : The ancient gems. CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 9783406088964 , pp. 12-16, 226, 240-242.

- Maria Elisa Micheli: Lo scarabeo Stosch: due disegni e una stampa. In: Prospettiva. No. 37, 1984, pp. 51-55. ( online )

- Max Kunze : Style and Utopia of History. Winckelmann's discovery of the Etruscan. In: Scientific journal of the Humboldt University in Berlin. Vol. 40, 1991, No. 6, pp. 69-73. ( online )

- Erika Zwierlein-Diehl : Antique gems and their afterlife. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 9783110194500 , pp. 82–84.

- Jean MacIntosh Turfa (Ed.): The Etruscan World. Routledge, New York 2013, ISBN 9781134055234 , pp. 502-504.

- Ulf R. Hansson: Stosch, Winckelmann, and the Allure of the Engraved Gems of the Ancients. In: MDCCC 1800. Vol. 3, 2014, pp. 13-33. ( online )

Web links

- Etruscan scarab, so-called Stosch's stone on the website of the German Digital Library

- Winckelmann, Firenze e gli Etruschi. Il padre dell'archeologia in Toscana. Parte Prima on the Letteratura artistica page

- Winckelmann, Firenze e gli Etruschi. Il padre dell'archeologia in Toscana. Part Seconda on the Letteratura artistica page

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Willmuth Arenhövel, Christa Schreiber: Berlin and the ancient world: catalog. German Archaeological Institute, Berlin 1979, p. 62.

- ^ Antonio Francesco Gori: Storia antiquaria etrusca. Florence 1749, p. 133. ( online )

- ^ Johann Joachim Winckelmann: Description of the pierres gravées de feu Monsieur le baron de Stosch. Florence 1760, p. 344. ( online )

- ^ Johann Joachim Winckelmann: History of the art of antiquity. Dresden 1764. ( online )

- ^ Johann Joachim Winckelmann: Monumenti antichi inediti. Volume 1, Rome 1767, p. 234. ( online )