The garden party

The Garden Party (dt. The Garden Party , translated in 1938 by Herberth E. Herlitschka ) is a short story of the New Zealand writer Katherine Mansfield , after the preliminary impression on February 4, 1922 in the Saturday Westminster Gazette and on 18 February 1922 in the corresponding week of release Weekly Westminster Gazette was published in book form in the anthology The Garden Party and Other Stories in America by Knopf Verlag in New York and in Collins Verlag in England in England . The story thematizes the experience of the fragility of the feeling of happiness in the confrontation of the young protagonist with death in a social milieu that is alien to her .

content

As in the other stories by Katharine Mansfield and in the short stories by James Joyce published twenty years earlier, the external plot of the story is rather simple or insignificant and mainly serves to create the framework for human encounters, whose impressions on the main character make a decisive change effect in their relationship to the environment.

Mrs. Sheridan, Laura, the main character , her two sisters and the house servants prepare a garden party when the weather is beautiful. Some workers have come to pitch a large tent for the celebration. On behalf of her mother, Laura gives the workers more precise instructions for setting up the tent in the garden. When talking to the workers, she finds them extremely nice and friendly. She regrets not having such friends, as her parents and her siblings had strictly forbidden her and her siblings to interact with people from such a socially inferior environment.

A florist brings a basket of pale red lilies that Mrs. Sheridan had ordered for the festival . Laura is amazed, the garden is in full bloom. While the cook is busy preparing the food for the celebration, a supplier brings the cream puffs that have also been ordered . He tells of a tragic accident with fatal outcome: the young wagoner Scott, who lived in a small, poor settlement along the road to the upper class Sheridan estate, fell miserably on the back of his head when his horse shied away from a tractor .

Confused about this death, Laura wants to cancel the garden party because it is not appropriate to celebrate a lively garden party with a dead person right in front of the door. To Laura's astonishment, however, both her sister Jose and her mother react coldly to this request; annoyed, they describe Laura as "silly" and "exaggerated". The mother only found out about the death by chance, so there was no reason to skip the celebration and it also does not show a lot of compassion to spoil everyone's fun, as Laura is doing now.

When her mother gives her a new hat to calm her down, Laura forgets about the death for the time being. After the successful completion of the garden party, Mr. Sheridan, who had returned in the meantime, mentioned the tragic accident again. Mrs. Sheridan then instructs Laura to bring the delicious leftover food from her celebration to the family of the deceased.

After some initial reluctance, the protagonist sets out on the way through the dark and smoky settlement to the meager huts of Scott family. At the insistence of Mrs. Scott's sister, she enters the house of the dead and sees the deceased lying on his death bed, apparently sleeping peacefully and dreaming. Laura feels the sight of him as wonderful and beautiful, but she still has to cry. On the way back she meets her brother Laurie, who accompanies her home.

Interpretative approach

Similar to James Joyce's The Dead , joyful festivity and death represent the two poles in a completely different social milieu, between which an initiation takes place, as it were ; the protagonist is introduced into a reality that makes her previous existence appear narrow and questionable.

As in other initiation stories, the plot breaks down into a chain of episodes in which each link is related to the change in the main character's attitudes. According to Fricker, Mansfield's narrative skill is evident in the fact that, on cursory reading , the reader is hardly aware of this connection, which forms the structural framework of the story.

The brief description of the wonderfully blooming garden at the beginning of the story forms the background and shows an important prerequisite for the success of the festival. Laura's brief conversation with the workers who put up the tent reveals her childlike impartiality towards members of another social class as well as her unspoiled sense for people as a whole, and at the same time prepares her later move to the poor workers' settlement.

So she states: “Oh, how extremely nice workers were [...]. Why could not she working as friends instead of having those silly boys with whom she danced, and the Sunday evening [sic] came to dinner? She would get along much better with men like that. [...] Everything is to blame for these absurd class differences. Well, as for her, she didn't feel it. Not a bit [sic], not a tiny bit [...] She felt like a working-class girl. " (P. 61f.)

In contrast, the class differences are a matter of course for both her mother and her older sister Jose that cannot be questioned. In perspective, as Durzak points out in his analysis of the story, “the great festival that is being prepared in the Sheridan's garden for the children and their friends, with a marquee, flowers, festive clothing and treats [...] is material wealth ahead of the way of life that most family members and especially the luxury- inclined Mrs. Sheridan perceive to be more or less natural ”.

The author carefully interspersed further references to, as Durzak calls it, " upper -class arrogance [...] permeated with Victorian self- confidence " in the world of the Sheridans. So lit u. a. the arrival of the splendor of flowers the meaning of the celebration for Mrs. Sheridan: She provides the pretext for the satisfaction of her own luxury needs as well as her extravagant whims. There is also talk of the “ gastronomic delicacies”, which Laura will later bring as a solution to the embarrassment like “crumbs from the rich man's table to the poor mourning family”.

In the same way, Laura's spontaneous social sympathy after the unfortunate news is opposed to the hard-heartedness and class consciousness of the sister ( "> Oh, Laura! <Jose was now really angry. [...] Her eyes became hard." , P. 70). Jose thinks Laura's sympathy is "exaggerated" and "silly" (p. 69). The mother reacts in the same way:

“But, my dear child, where is your common sense? We only found out about it by chance. If someone had died quite normally there - and I just can't imagine how they can stay alive in these narrow little holes at all - we would still celebrate our party, wouldn't we? " (P. 71)

Mrs. Sheridan is mainly occupied with trying out her new hat at the dressing table - a hat that is too youthful for her. She is relieved when she learns that the man "[d] och not in the garden" of the Sheridans had an accident. She dismisses Laura's sympathy with amusement as absurd, not to be taken seriously silliness:

“She just didn't take Laura seriously. ... "You're silly, Laura," she said coldly. > Such people don't expect us to make sacrifices. And it does not show a lot of compassion to spoil everyone's pleasure, as you are doing now. " (Pp. 71f.)

In the German translation by Heide Steiner, however, an essential structuring element of meaning from Katherine Mansfield's original version is lost in these passages. In the original text both Jose and Mrs. Sheridan describe Laura's reaction to the news of death several times in English as "absurd"

At these points, however, Steiner chose the term “silly” in the German version; in her transfer of the short story she overlooks Laura's feelings during her conversation with the workers in the garden, where the class differences in the original text also appear to be "absurd" (see above).

According to Fricker, who refers to the original English text in his analysis of the story, this very word "absurd", which is important for the veiled social "message" of the story, connects the three episodes of the story with one another and thus contributes to the artistic cohesion. Durzak and Staek also use the analysis of the original text to point to the simultaneous connection and delimitation of the two social opposing, but also parallel worlds in the text, which Mansfield artfully created .

If the class differences between rich and poor mean no difference to the protagonist in her experience, she gradually awakens “from the naive dream of childhood and the idea of a world in which everything is harmoniously in its place.” This is anticipated by the motif Song that her sister Jose practices at the piano for the garden party: "Life is sad when wishes linger, a dream-an adult ..." [sic] (p. 66); Scott, the wrecked carter, will also appear to Laura as "dreaming" on her deathbed. (P. 78)

Jose, who is already a copy of her mother, sings those verses "about a completely different life, to which grief and death belong, without any understanding"; for Laura they get their first meaning when she learns of the fatal accident.

At first, however, she remains trapped in the apparently idyllic , well-ordered, but socially isolated world of her family. When Mrs. Sheridan puts on her new hat Laura and it suits her very well, as she notices in her room in front of her self-image in the mirror ( "this lovely girl in the mirror, adorned with the black hat, the golden love-measure and a long velvet ribbon" , P. 72), she initially forgets about the death. When her older brother and the guests present tell her how “stunning” she looks with this “fabulous” hat (see p. 73), the memories of the death fade: “Oh, how lucky it is, to be together with lots of happy people [...] has never had such a delightful garden party [...] really successful ” . (P. 73)

The new hat has a symbolic secondary function in these scenes of the short story . According to Fricker, it can be interpreted as a sign of class as well as a symbol of vanity . Mrs. Sheridan would then be vanity in person or even an allegorical figure. Laura, on the other hand, shows a human or virtuous impulse in the conversation with the workers in the garden , but then also follows the lure of vanity and enjoys the compliments she receives for her lovely hat to the fullest.

The bread and butter in the opening part of the story can be seen as a counter-symbol to the elegant hat; it is also related to the delicacies with which Mrs. Sheridan entertains her guests and the remains of which Laura must later carry down to the poor. In her short story, Katherine Mansfield develops a dense motivic and symbolic network of relationships, which ensures artistic unity in the rather impressionistic narrative style, which limits the presentation of the actual event to the bare essentials. As Fricker writes in his analysis, "[...] the short episodes come together to form a whole from which no particle can be removed without [sic] creating a noticeable gap."

The first part is dedicated to the preparations for the garden festival and at the same time forms a kind of exhibition . The news of the death creates a "tangle"; the only hinted tension between Laura and her mother is prepared almost unnoticed in the conversation between Laura and the workers in the garden. The " conflict " is initially resolved by the hat motif, so that the garden party can apparently take a successful course. The turning point comes when, after the party, the father turns the conversation back to the tragic incident, and the mothers, without realizing it, with their embarrassment that Laura should carry the basket with the leftovers to the poor mourning family, to the " Disaster " at.

The catastrophe has the function of an initiation: Laura enters the house of the dead and faces the horror, but at the same time miracle of death, which is part of the larger, incomprehensible mystery of life. When Laura leaves the house of the dead and meets her brother crying on the way back, it turns out that the experience was too drastic for Laura to cope with it on her own: "'Isn't life," she stammered, "isn't life .. . <. But she couldn't explain what life was like. It didn't matter. He understood her. > Yes, isn't it, darling? <Says Laurie. " (P. 78)

The open ending of Das Gartenfest makes the reader pensive; like the protagonist, he sees himself “confronted with the riddle that forms the unreconciled juxtaposition not only of carefree wealth and ugly poverty, but above all of happy sociability and lonely death and ultimately of earthly and otherworldly happiness.” The word “happy”, used repeatedly “Connects the description of the garden festival with that of the dead like a bracket.

In terms of narration, the personal narrator ultimately feels completely at one with the child, from whose point of view he is portraying the entire event. However, Katherine Mansfield does not generally go as far as Henry James or James Joyce , in whose works the narrator and protagonist identify completely , if not even merge. There are only a few places in The Garden Festival in which an inner monologue takes place, which more or less directly records the course of consciousness.

For example, in the scene in her room in front of the mirror, Laura asks herself whether her mother is right after all and whether she is overstrained. (P. 72) The question triggers an impressionistic or associative chain of thought: The memory of the mourning family is awakened and faded at the same time, becomes unreal. The metaphorical comparison with the newspaper picture from 1920 illustrates both the indistinctness and the lack of commitment of the memory. A rapid change from dramatic and epic portrayal creates the impression of a now clear, conscious, now blurred, only half perceived sequence of thoughts and impressions.

The depiction of the scene at the death bed in the final part of the short story vividly depicts what moves the young girl on the threshold between childhood and adolescence , but which she cannot put into words: the superficial, purely physical happiness that the celebration of the rich conveys confronted with all the happiness that can also be bestowed on the poor in this world in death - and with it the riddle of human existence in its full depth.

“There was a young man lying soundly asleep, he was sleeping so deeply, so soundly, that he was far, far away from both of them. Oh, so remote, so peaceful. He dreamed. Never wake him up again. His head had sunk on the pillow, his eyes closed, they were blind under the closed lids. He was completely devoted to his dream. What do garden parties and baskets and lace clothes mean to him? He was far from all of these things. He was wonderful, beautiful. While they were laughing and while the band was playing, this miracle had come into the alley. Happy ... happy ... Everything is fine, said the sleeping face. Exactly how it should be. I am satisfied. ”(P. 78).

In this short story, Katherine Mansfield depicts the world as it presents itself to the minds and emotions of a sensitive girl on the border between childlike naivety and adolescence . The lower limit of Laura's age is indicated when, in the opening part of the short story, she runs away with bread and butter after receiving an order from her mother to take care of the placement of the tent in the garden. (P. 59f.) Her healthy self-confidence, her childlike carefree as well as her urge for the unconventional ( "> Laura, you are the artist among us" , p. 59) get a first damper when she tries to appear businesslike an affected tone in the voice - confronting the workers. (P. 60).

She likes the men, but when one of them thinks that the tent should be set up “where it really pops in the eye” (p. 61), her acquired sense of class is stimulated , because with his coarse colloquial choice of words the man supports her self-esteem come close, although she understands him well.

On the other hand, Laura is the one in the family who is the only one who finds the mother's suggestion, ironically described by the narrator as “one of her brilliant ideas”, to make the mourning family happy with the remaining delicacies of their garden party, as tactless and indecent. (P. 74f.). The story goes: “How strange, again she [Laura] seemed different from everyone else. Leftovers from their party. Would the poor woman really like that? " (P. 75)

The social criticism in The Garden Festival , cautiously indicated in this passage , emerges more clearly in the description of Laura's path into the house of the dead. In contrast to the initial description of the magnificent Sheridan estate, the alley in which the settlement is located is characterized as "dark and smoky" (p. 76). The short story goes on to say: “There was a faint humming from the poor little katen. In some of them there was a glow of light, like a crab, scurried past the window. ” The death house is described in a similar way: “ She [Laura] came into a small, low, poor kitchen that was lit by a smoky lamp. ” (P. 76)

At this point Laura is ashamed of her own social background and her completely inappropriate clothing in this situation: “Laura bowed her head and hurried on. She now wished that she had put on a coat. How her dress shimmered! And the big hat with the velvet ribbon - if only she had on another hat! ” (P. 76)

According to Durzak, Katharine Mansfield in Das Gartenfest as well as in her other short prose "perfected that subtly nuanced style of description that builds the social environment out of instantaneous impressions that are perceived as it were on the retina of language."

criticism

In 2007, in a collective review of the early short prose by Katherine Mansfield, the Berlin literary criticism emphasized the “perfection” that Mansfield values when writing. In the collections Das Gartenfest , Glück or Something Childlike, but Very Natural, there are stories in which “there is no comma, no interjection , no adjective too much or too little”. The author succeeds in writing stories that “touch”, “enchant”, “astonish” and “make the reader thoughtful or angry”.

In 2011, Bayerischer Rundfunk drew attention to The Garden Party as a “literary nibble”.

In an article on New Zealand literature in 2012, the Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung described Katherine Mansfield's Die Gartengesellschaft as a “masterful classic” of short stories.

Impact history

In the literary discussion of this short story, it is pointed out that The Garden Party is on par with the work of Chekhov or Joyce and further develops the tradition of short prose in a significant way.

Similar to Jane Austen in classical English literature, Katharine Mansfield in Das Gartenfest is about the literary design of the sensitive female way of seeing and feeling.

In recent English-language literature, The Garden Party is closest to the work of Virginia Woolf . In Das Gartenfest , Katharine Mansfield, in the literary form of an impressionistic short story, like Virginia Woolf in her women's novels, endeavors to capture the woman's attitude to life in existential moments of precarious happiness amid a world full of contrasts between harmony and disharmony with the help of a psychological - experimental narrative. Male characters only play a comparatively minor role with these two female writers, such as Laura's father or her brother Laurie, who appear only briefly in The Garden Party and are of no great importance.

Comparable to James Joyce's The Dead , Das Gartenfest is equally about the theme of the initiation of the main character between the extremes of happy festivity and sociability and lonely death in a completely different milieu.

In post-war German literature, Gabriele Wohmann ties in with the tradition of short prose and initiation story with her story The Birthday Society , first published in 1977 in the Böse Streich collection and other stories , thematically and motivically referring to The Garden Festival . In contrast to Wohmann's The Birthday Society , however, the immunization of the bourgeois world in Katherine Mansfield's Das Gartenfest is more resolutely lifted by perspective contrasts; Wohmann's story, on the other hand, as Durzak writes, shows the grotesque details of this way of life in a more pointed form.

In analyzing Mansfield's short prose, The Garden Party is assigned to its epiphany - or glimpse - tales . The literary term epiphany (from Greek: "epiphaneia", German: "appearance") goes back to a statement by James Joyce, which can be found in his early work Stephen Hero . Mansfield herself uses, as Silvia Mergenthal points out in her investigation of the short stories by Katherine Mansfield, “for this liminal experience of a sudden insight into unknown contexts” the expression glimpse (meaning “fleeting or brief insight ”). According to Mergenthal, this form of short prose in Das Gartenfest, as in other stories by Katherine Mansfield, is “ tightly organized texts [sic] that lead to a moment of cognition in which spatiotemporal laws appear suspended, and from this moment of cognition from characters like and readers to a retro prospects force revaluation of the previously happened. "

Others

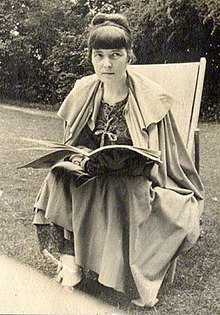

Katherine Mansfield wrote The Garden Party in 1922 at the age of 29, when she was already terminally ill. In 1917 she had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, but continued her old unsteady life and went on numerous trips, mostly to the Mediterranean, later on the advice of the doctors to Switzerland, sometimes with her husband from a second marriage, but more often with an old friend from youth.

She did not tolerate being alone. Her illustrious circle of friends included well-known writers such as DH Lawrence and his wife Frieda, Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard Sidney Woolf and the philosopher Bertrand Russell . On the background of her unhappy second marriage, she would have liked to enter into a closer relationship with this one and advertised with Russell, e.g. Z. with flattery and lies, for recognition and affection, was rejected.

In spite of her wide circle of friends and acquaintances, she basically felt isolated and lonely all her life. At the time The Garden Party was created , she was vacillating between the more realistic idea of being terminally ill and the hope of getting well again, living in the country and having children.

The siblings from the Sheridan family in The Garden Party had already appeared in the short story Her First Ball , written by Katherine Mansfield a year earlier and appearing in the anthology of the same name ( her first ball , translated by Heide Steiner in 1981). Laura, her sisters Meg and Jose and her brother Josie only play a minor role in Her First Ball .

The names of Meg and Jose as female figures are possibly taken from the girls' novel Little Women by the American writer Louisa May Alcott , published in 1868/1869 in two parts , which was very successful as a book for young people in the Anglo-American region and was particularly popular with young women has been.

Adaptations

In 1973, based on Katherine Mansfield's The Garden Party, a 25-minute short film directed by Jack Sholder with Maia Danziger, Jessica Harper and Michael Medeiros in the lead roles. The screenplay for the film was also written by Jack Sholder.

literature

- Manfred Durzak: The German short story of the present: author portraits - workshop discussions - interpretations. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , pp. 282-284.

- Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story. August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , pp. 203-213.

- Silvia Mergenthal: The Short Stories of Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield . In: Arno Löffler and Eberhard Späth (eds.): History of the English short story . Francke Verlag Tübingen and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-8252-2662-X , pp. 190-206.

- Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations. Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , pp. 67-96.

Web links

- Literature from and about "The Garden Festival" in the catalog of the German National Library

- The Garden Party . On: University of Pennsylvania Digital Library. Retrieved October 30, 2013 (original English text of the first edition from Knopf Verlag)

- Biography, Literature & Sources for Katherine Mansfield FemBio of the Institute for Women's Biography Research

Individual evidence

- ↑ On the history of the publication, cf. the information in WorldCat and in the "explanatory notes" by Dan Davin in the annotated collection he edited: Katherine Mansfield · Selected Stories. Oxford World's Classics, Oxford University Press, London 1953. After the first translation by Herlitschka, the story was translated into German again in 1968 by Elisabeth Schnack and in 1995 by Heide Steiner. a. also published as paperback, for example in 1980 by Münchener Taschenbuch Verlag , ISBN 3-423-09136-3 , 1988 and 1993 by Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag , ISBN 3-596-29269-7 , or 1995 and 1998 by Frankfurter Insel Verlag , ISBN 3- 458-33905-1 .

- ^ Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story. August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 205.

- ↑ Cf. Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 205, and similarly Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 281 f. Wolfgang Staek also interprets the garden party as a "story of initiation". See the same: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , p. 95 f.

- ↑ Cf. Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 205.

- ↑ Quoted from Katherine Mansfield: Das Gartenfest und other stories , translated and edited by Heide Steiner in Insel Verlag 1995, ISBN 3-458-33424-6 . Cf. on this interpretation Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 205, as well as Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Discussions - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3 -15-010293-6 , p. 282.

- ↑ Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 282. This aspect is also detailed with the indication of various textual references highlighted in Staek's analysis. See Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , pp. 86 and 89ff.

- ↑ Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , pp. 282f.

- ↑ See Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 206, and Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3 -15-010293-6 , pp. 282f.

- ↑ See more detailed on this interpretation approach Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 206. Likewise, Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , p. 88, and Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3- 15-010293-6 , p. 282.

- ↑ See e.g. B. the copy of the original text by Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , pp. 74f.

- ^ Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , pp. 206f.

- ↑ Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 282f, also detailed Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation Model interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , p. 88ff

- ↑ Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 282.

- ↑ Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 282.

- ↑ Fricker sees here in his interpretation references to “Mankind and Everyman” in medieval morality play . The garden party can then be compared with Vanity Fair in Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress , where Christian or Christ, the main allegorical figure, feels like a stranger in several places in his environment, just like Laura. See Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , pp. 206f. For the hat symbolism cf. also Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , p. 88.

- ^ Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 207f and on the symbolism of bread and butter p. 211f. On the motif-symbolic network in Das Gartenfest see also Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , pp. 89-95.

- ↑ Cf. Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , pp. 207f. See also Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 282.

- ^ On this interpretation, see Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 208f, as well as in detail the section Laura's Initiation in: Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , pp. 95f

- ↑ Cf. Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , pp. 208f. See also Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , p. 96.

- ↑ See in detail Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 209.

- ^ Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 210 f. See also the interpretation of this passage in Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations , Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 283, and Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , p. 96.

- ↑ See the interpretation as far as Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , pp. 210f. See also the brief description in Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations . Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , p. 9f.

- ↑ See also Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 213. See also Manfred Durzak: The German short story of the present: author portraits - workshop discussions - interpretations. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , p. 282.

- ↑ On the contrasting comparison in the description of the property of the wealthy Sheridans and the dwelling of the impoverished family of the deceased, cf. the section Contrasts and Parallels in the Two Worlds in: Wolfgang Staek: Stories of Initiation · Model Interpretations. Klett Verlag, Stuttgart 1979, ISBN 3-12-578430-1 , pp. 89-91.

- ↑ Manfred Durzak: The German short story of the present: author portraits - workshop discussions - interpretations. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , pp. 281f.

- ↑ Modern Souls in the Meat · Katherine Mansfield's early stories . In: Die Berliner Literaturkritik , July 5, 2007. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- ↑ Bites of literature: The Garden Party by Katherine Mansfield . On: Bayerischer Rundfunk , June 22, 2011. Accessed October 30, 2013.

- ↑ New Zealand presents itself at the book fair . In: Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung , October 5, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ↑ Cf. more precisely the information and evidence from Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): The English short story . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , p. 213.

- ↑ On these aspects of the history of the impact of The Garden Party, cf. in more detail the information and evidence from Robert Fricker: Karl Heinz Göller and Gerhard Hoffmann (eds.): Die Englische Kurzgeschichte . August Bagel Verlag, Düsseldorf 1972, ISBN 3-513-02222-0 , pp. 203f., 205, 208, 212f.

- ↑ Cf. Manfred Durzak: The German Short History of the Present: Author Portraits - Workshop Talks - Interpretations. Reclam-Verlag, Stuttgart 1980, 2nd edition 1983, ISBN 3-15-010293-6 , pp. 281f.

- ↑ Silvia Mergenthal: The Short Stories of Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield . In: Arno Löffler and Eberhard Späth (eds.): History of the English short story . Francke Verlag Tübingen and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-8252-2662-X , pp. 190–206, here pp. 190f.

- ↑ Silvia Mergenthal: The Short Stories of Virginia Woolf and Katherine Mansfield . In: Arno Löffler and Eberhard Späth (eds.): History of the English short story . Francke Verlag Tübingen and Basel 2005, ISBN 3-8252-2662-X , pp. 190–206, here pp. 190f. and p. 193

- ↑ The master of the short story . On: Deutschlandradio Kultur , October 7, 2012. Retrieved October 30, 2013. See also Martina Sulner's biographical background in her above-mentioned article New Zealand is presented at the book fair in the Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung on October 5, 2012.

- ↑ Her First Ball was first published by Sphere Verlag in London in 1921 and was later included in various anthologies. The German translation by Heide Steiner was first published in 1981 in the Katherine Mansfield Collection : Selected Works · Volume 1 , ed. by Wolfgang Wicht, published by Leipziger Insel Verlag and is u. a. also contained in the Katherine Mansfield collection , Das Gartenfest and other stories published by Steiner in various editions (cf. the information above).

- ^ The Garden Party (1973) . On: Internet Movie Database . Retrieved October 30, 2013.