Vision (religion)

A vision (from the Latin visio "appearance, sight") is a subjective pictorial experience of something imperceptible to the senses, which, however, appears to the experiencing - the visionary - as real and, in the religious sense, is attributed to the influence of some otherworldly power. In addition, auditory impressions often occur, mostly as spoken words.

Sometimes the visionary receives impressions that seem to come from other sense organs. When it comes to a pure listening experience, one speaks in religious studies of “audition” (from Latin audire “to hear”), but colloquially the difference between imageless inner perceptions and pictorial experiences is hardly taken into account.

Concept and concept history

The term visio was common in the Latin hagiographic literature (life descriptions of saints) in the Middle Ages and there was also a vision literature as a separate literary genre. In the early 14th century, the word was adopted from the (Middle) Latin language into German. It was partly Germanized ( visiôn , visiûn , visiûne ), partly it was left in its original form as visio and it was also declined in Latin in German texts, which occurred until the end of the 17th century. The oldest evidence of Germanization can be found in Meister Eckhart († 1327/1328). A synonym already in use in Middle High German was “face” (plural “faces”, meaning “seen”).

Since the number of fundamental skeptics increased sharply in the early modern period and the visions in the Age of Enlightenment were largely denied an objective meaning, the term "vision" was also given the connotation "illusion", "delusion", "(fever) dream image" , "Imagination", "imagination".

Because many visions refer to the future, the word was given the general meaning “vision of the future” in the sense of a wishful thinking (rarely feared) or a utopia that is considered feasible . Outside of religious contexts, one speaks of “visions of the future”. What is meant are mostly bold, in some cases fantastic concepts, drafts and ideals whose realization is planned and which arouse enthusiasm in receptive circles. In this sense, especially in politics and business, there is talk of visions, such as the vision of a united Europe. An often-cited example is the speech I Have a Dream by Martin Luther King , given in 1963 , in which he developed his vision of a united and just society of blacks and whites. This secularized concept of vision, for its part, has an effect on the use of religious language, for example when speaking of visions of a future ecumenical movement .

The expression “visionary” as well as the associated adjective “visionary” was taken from French ( visionnaire ) into German. The word was Germanized in the 18th century. The connotation “dreamer”, “enthusiast”, “fantastic” was present from the start. Today the term is often used non-religiously to denote people who - as politicians or inventors - formulate and implement courageous, groundbreaking ideas.

Types of visions

A vision can also be received in a dream, then one speaks of a dream vision . Their distinction from ordinary dreams is made in a religious context analogous to the distinction between waking visions (visions in the waking state) and hallucinations. The claim to truth associated with dream visions is often judged more skeptically in religious circles in which the possibility of “real” visions is affirmed than with waking visions.

Revelation (Latin revelatio ) is a special form of vision . In a visionary experience of revelation, the visionary thinks he is receiving a message with which divine truth is revealed, usually with the instruction to proclaim it. With some visions, the visionary believes that past, future or spatially distant events can be perceived optically and acoustically, as if they were taking place in his presence. If the claim is made that something future will be revealed in the vision, then it is a prophetic (seeric) vision which is expressed verbally as prophecy . Divination differs from ordinary divination in the specifically religious concern that forms the core of the message. Often it is about the future of the Church or of the visionary's own order or about the future fate of all humanity or of certain peoples. But prophecy about the fate of individual personalities also plays a major role. In addition to the prophetic vision, the teaching vision is a special type. It is primarily aimed at teaching and imparting knowledge or moral commandments. Therefore the pictorial elements take a back seat to the auditory ones.

As a rule, only one person, the visionary, is directly affected by a vision, none of the others have direct access to the experience. In some cases, however, entire groups claim to have perceived the visual phenomena of the vision at the same time. This is especially the case with some Marian apparitions .

Interpretation and exploration

As very widespread cultural-historical phenomena, visions and their traditional religious interpretations are an important subject of religious studies, ethnological , historical and literary history research. Historians ask in particular to what extent religious or political ideas, wishes, fears and goals of the visionaries and their environment have influenced the traditional representations and interpretations of the visions. They also examine how visions have been instrumentalized for political and religious purposes.

In a religious context, if a vision is viewed as "real" (not a hallucination ), it is traced back to a real external cause. A positive interpretation of the experience is a deity or an entity acting on behalf of the deity (for example an angel or saint ), and a negative interpretation is a demon or devil . It is assumed that the originator of the vision wants to send a message to the visionary and about him to a certain group of people or to humanity. Reports on visions often serve to legitimize or confirm religious worldviews or to authenticate and reinforce individual religious doctrinal statements and instructions. Such a religious interpretation of a vision experience is often justified by the fact that a message was conveyed in the vision, the extraordinary and extraordinarily impressive content of which exceeds the level of knowledge and everyday horizon of the visionary and can hardly be explained in a normal way, which speaks for authenticity. In addition, visionaries describe the type of perception during the vision as so stirring, moving and shocking that, from their point of view, only a power with superhuman abilities comes into consideration.

Since religious visions are subjective experiences that are only known from the descriptions given by the visionaries afterwards, they largely elude scientific investigation. However, it is possible to compare the experiences described and accompanying physical and mental symptoms with visual and acoustic hallucinations of mentally ill people and with phenomena in deliberately created exceptional states (intoxication, ecstasy ). Psychological interpretations are based on such comparisons, the representatives of which deny the visions or psychosomatic phenomena an objective correlate. Skeptics and opponents of religious worldviews regard the visions as pathological illusions, delusions or inventions for the purpose of deliberate deception. Defenders of a religious interpretation of the visions counter this that any similarities with psychopathological phenomena are only apparent or external and that they are in reality incomparable, since the visionaries do not suffer from any mental illness.

CG Jung defined the vision as a process that is like a dream but takes place in the waking state. It emerges from the unconscious next to conscious perception and is “nothing more than a momentary break in of an unconscious content into the continuity of consciousness”. As in dreams and hallucinations, the emergence of autonomous complexes of the psyche is clearly recognizable in visions. From this it can be seen that the psyche as a whole is not an indivisible unit, but “a divisible and more or less divided whole”.

Religious Traditions

For many peoples of North America and regionally South America, the conscious search for visions is an important spiritual practice of the respective ethnic religions .

Hinduism

Numerous visionary accounts have come down to us in the religious literature of Hinduism. These are mainly visions of gods. Detailed descriptions of visions of the hereafter can be found in the epic Mahabharata , especially in the Bhagavadgita . The visionaries are mostly ascetics . Ramakrishna was an influential visionary of the 19th century who was also known outside of India .

Judaism

In the Tanach visionary seeing is expressed with the verbs rā'āh and ḥāzāh . The corresponding nouns for " seer " are also used, and there is a name for the religious vision (ḥāzôn) , which is synonymous with prophecy. Often a prophet legitimized himself through a calling experience that included vision and audition. A special form of the calling vision was the throne room vision, in which the heavenly councilor appears to the visionary.

Christianity

In the New Testament , visions are of central importance in several places. The Revelation of John expressly reports several visions, e.g. B. in ( Rev 1,10 EU ) which extend over the entire book. In the other writings of the New Testament, visions often occur at turning points in the narratives: Joseph flees to Egypt after a vision with Mary and Jesus ( Mt 2.13 EU ). Ananias of Damascus searches for a vision of Saul in Acts 9 : 10-17 EU . Peter justifies with a vision that he not only preached the gospel to the Jews, but also to the Gentiles, Acts 11 : 5-18 EU . Paul travels to Macedonia on a nocturnal vision, Acts 16: 9-10 EU . In his second letter to the Corinthians ( 2 Cor 12 : 1–6 EU ) Paul reports on a visionary ascension into heaven that one of his fellow campaigners experienced.

The desert fathers of late antiquity often saw visions in which the soul of a deceased saint was seen ascending to heaven. Visions of the devil and demons were also widespread.

In the Middle Ages, it was above all the extremely popular dialogues of Gregory the Great , which contain an abundance of visions, that contributed to the spread of the conviction that it was always to be expected that otherworldly powers would make themselves known through visions. The Dialogi were exemplary for the literary genre of medieval narratives of visions of the afterlife . But there were also skeptical voices who warned against gullibility and pointed out that supposed heavenly appearances could also be deceptions of demonic origin or products of the imagination. In 1401 the theologian Jean Gerson wrote De distinctione verarum visionum a falsis (On the distinction between real visions and false ones ) . He called for critical examination, but said that certainty could not be achieved with it.

From the end of the 13th century, the number of recorded vision reports from German nunneries increased. They contained statements not only on theological, but also on political and social issues. In this way, among other things, attempts were made to establish or legitimize certain customs and to justify certain exercises of piety. The visionary Christine Ebner made a claim to truth for her convictions, which she justified with her vision experience and to which she wanted to hold on uncompromisingly even against the contradiction of scholars and priests.

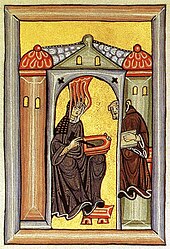

The most famous Christian visionaries of the Middle Ages include Dominikus , Gertrud von Helfta , Hildegard von Bingen , Juliana von Norwich , Juliana von Lüttich , Lutgard von Tongern , Mechthild von Hackeborn , Mechthild von Magdeburg and Katharina von Siena . In modern times u. a. Bernadette Soubirous , Margareta Maria Alacoque , Mirjam von Abelin , Teresa von Ávila and Baba Wanga received a lot of attention. The Marian apparitions are a particularly widespread type of vision .

In Catholicism, from the church's point of view, visions that took place after the revelation of Christ are “ private revelations ”; the possibility of a new public revelation binding for all believers is denied. The church teaching office has to decide on the authenticity of a vision . The decision is made by the responsible bishop. A central criterion here is that there must be no discrepancy between the content of the vision and the Church's teaching. If a vision is recognized by the church, it does not mean that the church vouches for the divine origin of the vision, but only that the Magisterium does not raise any objection to the possibility of authenticity.

See also

Source collection

- Peter Dinzelbacher (ed.): Medieval vision literature. An anthology . Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1989, ISBN 3-534-01229-1 (Latin and vernacular texts with translation)

literature

Overview representations

- Pierre Adnès: Visions . In: Dictionnaire de spiritualité , vol. 16, Beauchesne, Paris 1994, col. 949-1002

- Marco Frenschkowski , Norbert Mette : Vision . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Volume 35, de Gruyter, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-017781-1 , pp. 117-150 (deals with visions in a number of religions, mainly in Judaism and Christianity)

- Felicitas D. Goodman : Visions . In: Lindsay Jones (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Religion , 2nd Edition, Vol. 14, Thomson Gale, Detroit a. a. 2005, ISBN 0-02-865983-X, pp. 9610-9617

- Karl Hoheisel u. a .: Vision / vision report . In: Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart , 4th edition, Vol. 8, Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-16-146948-8 , Sp. 1126–1134

- Peter Dinzelbacher u. a .: Visio (n), literature. In: Lexikon des Mittelalters , Vol. 8, LexMA, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-89659-908-9 , Sp. 1734-1747

Overall representations

- Ernst Benz : The vision. Forms of experience and world of images . Klett, Stuttgart 1969

Studies on individual epochs

- Peter Dinzelbacher : Vision and vision literature in the Middle Ages. Hiersemann, Stuttgart 1981, ISBN 3-7772-8106-9 ; 2nd, revised and significantly expanded edition there 2017 (= monographs on the history of the Middle Ages. Volume 64)

- Hans Joachim Kamphausen: Dream and Vision in the Latin Poetry of the Carolingian Period . Peter Lang, Bern 1975, ISBN 3-261-00997-7

- Bart J. Koet (Ed.): Dreams as Divine Communication in Christianity: From Hermas to Aquinas . Peeters, Leuven 2012, ISBN 978-90-429-2757-5

- Sabine Tanz , Ernst Werner : Late medieval lay mentalities as reflected in visions, revelations and prophecies. Peter Lang, Frankfurt a. M. 1993, ISBN 3-631-44099-5

Representations from a Catholic theological point of view

- Ulrich Niemann , Marion Wagner: Visions. Work of God or Product of Man? Theology and human sciences in conversation. Pustet, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7917-1954-8

- Karl Rahner : Visions and Prophecies. On mysticism and the experience of transcendence. Herder, Freiburg 1989, ISBN 3-451-21462-8 (new edition of the 2nd edition from 1958)

iconography

- Liselotte Schütz: Visions . In: Engelbert Kirschbaum (Ed.): Lexicon of Christian Iconography , Vol. 4, Herder, Rom / Freiburg 1972, ISBN 3-451-14494-8 , Sp. 461-463

Web links

Remarks

- ↑ Hans Schulz u. a. (Ed.): German Foreign Dictionary , Vol. 6, Berlin 1983, pp. 217–220.

- ↑ Matthias Lexer : Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuch , Vol. 1, Stuttgart 1974 (reprint of the Leipzig edition 1872), Col. 913.

- ↑ See the article Vision, apparition in the Encyclopédie , Vol. 17, Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1967 (reprint of the 1765 edition), p. 343 and the examples in Hans Schulz et al. a. (Ed.): German Foreign Dictionary , Vol. 6, Berlin 1983, pp. 218–220.

- ↑ Examples from Hans Schulz u. a. (Ed.): German Foreign Dictionary , Vol. 6, Berlin 1983, pp. 218–220.

- ↑ Norbert Mette: Vision VI. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. 35, Berlin 2003, pp. 148–150.

- ↑ Hans Schulz u. a. (Ed.): German Foreign Dictionary , Vol. 6, Berlin 1983, pp. 221f. (with receipts)

- ↑ See also Ernst Benz: Die Vision , Stuttgart 1969, pp. 104–130.

- ↑ See Ernst Benz: Die Vision , Stuttgart 1969, pp. 131–149.

- ↑ Ernst Benz: Die Vision , Stuttgart 1969, pp. 150–162.

- ↑ Examples from Gottfried Hierzenberger, Otto Nedomansky: Apparitions and Messages of the Mother of God Maria. Complete documentation through two millennia , Augsburg 1997, p. 38, 250–260.

- ↑ See, for example, the relevant monograph by Paul Edward Dutton: The politics of dreaming in the Carolingian empire , Lincoln 1994, and Roland Pauler: Visionen als Propagandamittel der Gregors VII. In: Mediaevistik 7, 1994, pp. 155–179.

- ↑ Wilhelm Pöll: Religionspsychologie , München 1965, pp. 413–437, 441–444, 486–496 offers a description of the psychology of religion.

- ^ Peter Dinzelbacher : Visions. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 1447 f.

- ↑ See for the controversial discussion of this topic Ernst Benz: Die Vision , Stuttgart 1969, pp. 85–88; Marco Frenschkowski: Vision. I. Religious history . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. 35, Berlin 2003, pp. 117–124, here: 122 (and bibliography p. 124).

- ↑ Carl Gustav Jung: The dynamic of the unconscious (= Collected Works , Vol. 8), Zurich / Stuttgart 1967, p. 347f.

- ^ Walter Hirschberg (founder), Wolfgang Müller (editor): Dictionary of Ethnology. New edition, 2nd edition, Reimer, Berlin 2005. pp. 398–399.

- ^ Marco Frenschkowski: Vision. I. Religious history . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. 35, Berlin 2003, pp. 117–124, here: 120.

- ^ Marco Frenschkowski: Vision. II. Old Testament. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. 35, Berlin 2003, pp. 124–128; Hans F. Fuhs: rā'āh . In: Heinz-Josef Fabry, Helmer Ringgren (Hrsg.): Theological Dictionary to the Old Testament , Vol. 7, Stuttgart 1993, Sp. 225–266, here: 260–263; Alfred Jepsen : ḥāzāh . In: Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren (Hrsg.): Theological dictionary to the Old Testament , Vol. 2, Stuttgart 1977, Sp. 822-835.

- ^ Marco Frenschkowski: Vision. IV. New Testament. In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie , Vol. 35, Berlin 2003, pp. 133-137.

- ↑ See also Ernst Benz : Paulus als Visionär (= treatises of the Academy of Sciences and Literature. Humanities and social science class. Born 1952, Volume 2).

- ^ Pierre Adnès: Visions . In: Dictionnaire de spiritualité , Vol. 16, Paris 1994, Col. 949-1002, here: 961-963.

- ^ Pierre Adnès: Visions . In: Dictionnaire de spiritualité , Vol. 16, Paris 1994, Sp. 949-1002, here: 967f.

- ^ Pierre Adnès: Visions . In: Dictionnaire de spiritualité , vol. 16, Paris 1994, col. 949-1002, here: 980.

- ^ Siegfried Ringler : Vites of grace from southern German women's monasteries of the 14th century - writing vitals as a mystical doctrine. In: Dietrich Schmidtke (ed.): Minnichlichiu gotes discernusse , Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt 1990, pp. 89-104, here: 94-101.

- ^ See on the dogmatic and canonical handling of visions Marion Wagner: The phenomenon of vision in theological view . In: Ulrich Niemann, Marion Wagner: Visionen , Regensburg 2005, pp. 11–59, here: 24–48.

- ↑ See Dieter Kremers : Review. In: German Dante Yearbook. Volume 64, 1989, pp. 173-178.