Wilhelm Lubosch

Wilhelm Lubosch (born March 28, 1875 in Berlin , † February 16, 1938 in Gundelsheim (Württemberg) ) was a German anatomist (physician and zoologist) and morphologist .

Career and performance

After graduating from high school, studying medicine in Berlin (his dissertation with Heinrich Wilhelm Waldeyer dealt with the comparative anatomy of the roots of the 11th cerebral nerve) and three years as assistant to Carl Hasse at the University of Breslau , Lubosch worked as an assistant to Friedrich Maurer (1859-1936) Jena, u. a. zu Albert von Kölliker , Hermann Braus and Ernst Haeckel , completed his habilitation (private lecturer, 1902) and became titular professor here in 1907. As such, he moved to Würzburg in 1912 , where he was appointed associate professor in 1916 (still “in the field”) and full professor of topographic anatomy in 1921 (succeeding Oskar Schultze ) - and remained until his death. From 1925 Lubosch was head of the department for topographical and applied anatomy. From then on, Hans Petersen worked with him at the Würzburg Anatomical Institute.

Lubosch's name is particularly associated with the seven-volume handbook of the comparative anatomy of vertebrates , which he shared with Louis Bolk (Amsterdam; 1845–1930), Ernst Göppert (Marburg; 1866–1945) and Erich Kallius (Heidelberg; 1867–1935), under Collaboration of numerous German and foreign experts, published (Berlin and Vienna (Urban & Schwarzenberg) 1931-39; new printing Amsterdam (Asher) 1967; total 6380 pages) - whereby he was the spiritus rector of this company (the last attempt at a comprehensive overall Illustration) - and that used up his strength prematurely, so that he died of heart failure at the same time as it was completed (especially since the most recently completed (V) volume contained the most extensive contribution by Lubosch himself, on the head muscles (1938) the index volume appeared posthumously). But the political situation in Germany probably also played a role in this, which anti (neo) Darwinists like him were not beneficial. The (3rd) German Reich promoted a special “German science”, but in the field of biology one was definitely in the Darwinian waters, one sees once from the folk- social Darwinian race theory (“people without space” etc.) and fought against all (in the broadest sense) “ Lamarckist ” dissenters who were so common among German biologists (e.g. Hans Böker ). And Lubosch held z. B. Between individual and average anatomy (1924a) apparently nothing of a “racial anatomy” ( going back to the anatomists Camper and Soemmering at the end of the 18th century ). That's why (?) He only got an obituary long after the war (in the "Anatomische Nachrichten").

Lubosch made a. a. important contributions to the microanatomy of the musculoskeletal system (1910, 1937); the system of the joints is essentially due to him. The essence of the muscles is "omnisience" (the all-round approach) - the movement of two skeletal parts towards each other is something derived. The medical floor plans and auxiliary books he published enjoyed great popularity for a long time, but were valid abroad e.g. T. as top-heavy.- Thanks to his constant interest in the theoretical foundations of comparative anatomy, he dealt with morphology as a science that reveals regularities without causal analysis. Goethe could have accentuated this, whom Lubosch never denied as a role model (cf. Lubosch 1918a, 1919; one also reads his beautiful “History of Comparative Anatomy” in Volume I of the manual , 1931: 3-76). Hence Lubosch's advocacy of “humanistic” education, especially for natural scientists (1920c): Antiquity as a model for scientific thinking without the predominance of the causality principle, which has long been considered the only valid one - and not just because of the technical terms that can be traced back to Latin and Greek. However, all of the “last morphologists” such as Jan Versluys and Wilhelm Marinelli never clearly systematized their positions - Marinelli, for example, only mentioned the matter occasionally in a lecture. Rupert Riedl (2006) was the only one today who felt the loss of this morphology and regretted it shortly before his death.

Lubosch's theory problems

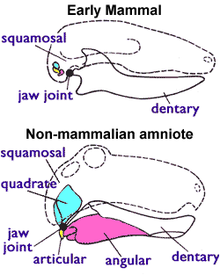

As a comparative anatomist, Lubosch was preoccupied with some questions for almost his entire life - one of them was: How did the squamosodental joint in mammals come about ? All other vertebrates, if they have jaws , have their jaw joint between the quadratum and the articular (this joint still exists, but in humans in the middle ear ). Lubosch believed that the new joint might have already appeared in “fish-like mammalian ancestors”, first between pieces of cartilage on the lower jaw in the ligamentum primordiale (= ligamentum maxillomandibulare posterius ), which Lubosch had with regard to the 'origin' ( primordium ) of the so named the new temporomandibular joint. This theory was wrong, but we owe it to a number of important publications on the trigeminal nerve muscles in bony fish (culminating in 1929). Lubosch (1923a) also discovered streptognathy in sea parrots (which have an additional intramandibular joint between the dentate and articular joint ) as an apparent support of the theory - it is thus evident that a movable lower jaw can also be used for powerful biting. However, Lubosch did not go into the functional details that would have shown him the untenability of his theory - with the explanation: "There are a lot more forms than functions anyway." Whoever thinks this way cannot, of course, gain too much from Darwinism - he understands the living nature as the area of the undirected luxurizing of purposeless creative forces . But Lubosch was neither a declared vitalist nor an orthogeneticist ; He expressly rejected the holism (Hans Bökers), which was still widespread at the time, with the apt sentence “The whole really exists; but it is only recognizable in the relations of its parts ”, even if (with Aristotle )“ the whole is before the parts ”.

The question of the genesis of the secondary temporomandibular joint already preoccupied idealistic morphologists; on the other hand, the following problem emerged only as a result of Darwin's doctrine of descent. In the three preliminary publications (partly as a result of being called up) on the trigeminal muscles of fish, Lubosch (especially 1917) mentions his new, completely opposite view of the relationship of taxa : through " polyphyly ". He had scooped "suspect" probably already at work on the dissertation, as the shapes of the accessory nerve of Willis could not be reduced to a simple primitive shape. And in his myological examinations he repeatedly came across features that are commonly interpreted as convergences . But since he disregarded functional differences anyway, he came up with the idea, which today seems almost absurd, that these “convergences” must be indications of a real relationship (common descent). As far as is known, there has recently been no evidence or evidence of phyletic “cross-related kinship”, but this possibility can be expected for certain past times, even if we still cannot understand why it was caused. In such “mutation periods” (times when species become unstable), the possibility of fertile crossbreeding is still to be assumed despite the already “initiated” hereditary separation [isolation] of groups of individuals [populations] of the species. These crossings, from which a progeny with manifold new, constant combinations of characteristics would grow, could explain “the phenomena observed so often in the animal kingdom that the same characteristic is found in different kinds and orders and that one kind or order has characteristics in itself combined that occur in isolation in other species "(Lubosch 1920a)

In this way, Lubosch wanted to interpret the occurrence of "shark features" in Teleosts or B. the muscle portion A 1 β in the masticatory muscles of Zoarces , which he counted among the Blennioids, while the muscle is otherwise only to be found in Gadoids. The well-known phenomenon that insect larvae sometimes another taxonomy "follow" as the associated imagines , belong equally here. Lubosch (1920a) wanted to systematically prove his new theory, which - in contrast to Darwin's theory of descent - he provocatively called "the theory of ascendency " by means of a study on the Steinheimer snails. This is a rich material of small celestial snails ( Gyraulus ) from the fossil lake of the Steinheim meteorite crater, which has existed for several hundred thousand years and can therefore offer phylogenetic series. Here everything depends on the interpretation - after all, Franz Hilgendorf (1866) had already provided the first “proof” of the theory of descent on the same material ! (In formal terms, Lubosch justifies his "ascendency" quite illogically with the backward increase in the number of physical ancestors in powers of two per generation, which "must" automatically lead to species boundaries being exceeded very soon.)

In 1929 the "kinship over the cross" or [real] polyphyly (in the case of the bony fish) is still being discussed, after which it apparently took a back seat as a result of the editing work on the manual - but whether Lubosch has ever given it up remains uncertain. To this day it is discussed among esotericists and opponents of Darwinism.

honors and awards

In 1912 Wilhelm Lubosch received the Carus Prize from the Leopoldina .

Fonts (selection)

Only a select few of the publications in journals are included.

- The comparative anatomy of the accessorius origin.- Berlin (Schade) 1898 (dissertation) .- Extended version: Comparative anatomical studies on the origin and phylogenesis of the N. accessorius Willisii.- Archive for microscopic anatomy 54 (1899): 514-602

- About the nucleolar substance of the ripening triton egg together with considerations about the nature of the egg ripening - Jena (G. Fischer) 1902 (Habilit. -schrift)

- On the sex differentiation in Ammocoetes.- Verh. Anat. Ges. 17 (1903).

- The development and metamorphosis of the olfactory organ of Petromyzon and its significance for the comparative anatomy of the olfactory organ.- Jena. Z. Naturwiss. 40 (1905): 95-148

- Over the meniscus in the temporomandibular joint of the human - Anat. 29 (1906a): 417-431

- On variations in the articular tuberosity of the human temporomandibular joint and their morphological significance.- Morph. Jb. 35 (1906b): 322 ff.

- Comparative anatomy of the sensory organs of vertebrates.- Leipzig (Teubner) 1910a

- Construction and formation of vertebrate joints: a morphological and histogenetic study.- Jena (G. Fischer) 1910b

- Some considerations about the value of morphological training for the medical practitioner.- Sonderdr., (Münchn. Mediz. Wochenschr .; Lehmann) 1912

- About the Würzburg anatomist Ignaz Döllinger, introduced and concluded by discussions about Schopenhauer's evolutionism, - Yearbook of the Schopenhauer Society IV (1915): 105-127

- The jaw muscles of the bony fish: maxillomandibular ligament. Essence of streptognathy and genesis of the squamosodental joint. (Comparative anatomy of the jaw muscles of vertebrates in five parts: II.) - Jena. Z. Naturwiss. 54: 276-332 (1917)

- The academy dispute between Geoffroy St.-Hilaire and Cuvier in 1830 and his guiding thoughts - Biological Zentralblatt 38 (1918a): 357 ff.

- New results in research into the structure of the trigeminal muscles - Würzburg (Kabitzsch) 1918b.

- What does comparative anatomical science owe to the work of Goethe? - Weimar (Verl. D. Goethe-Ges.) 1919

- The problem of animal genealogy. In addition to a discussion of the genealogical connection of the Steinheim snails - Arch. Mikrosk. Anat 94 (1920a): 459-499

- The problem of form as an object of anatomical science and the task of reforming anatomical teaching - Jena (G. Fischer) 1920b

- The importance of humanistic education for the natural sciences. Lecture given in the local group of Würzburg of the Association of Friends of the Humanistic Gymnasium - Jena (G. Fischer) 1920c

- Reflections on the nature of the German universities. Ignaz Döllinger [1819]. - Würzburg (Kabitzsch & Mönnich) 1920d

- Obituary for Oskar Schultze, held in the memorial session of the Physical-Medical Society in Würzburg on December 2, 1920.- In: Negotiations of the Physical-Medical Society in Würzburg. New series, Volume 46, 1921, pp. 19-45.

- Average anatomy and individual anatomy (lecture) .- Jena (G. Fischer) 1922a

- Carl Gegenbaur.- CVs from Franconia II: 144-157 (1922b)

- Emil Selenka, a commemorative sheet for the eightieth anniversary of his birthday on February 27th, - Naturwissenschaften 10 (1922c): 179-181

- Oskar Schultze: Atlas and brief textbook of topographical and applied anatomy - Munich (JF Lehmanns Verl.) - 3rd revised. Edition by Wilhelm Lubosch, 1922d. archive.org 4th edition 1936.

- The jaw apparatus of the scarids and the question of streptognathy.- Anatomischer Anzeiger 57 (1923a) Suppl .: 10–29

- Normal development history of the female genital organs in humans. In: Biology and Pathology of Women. Edited by Halban and Seitz, Volume I.- Berlin (Urban & Schwarzenberg) 1923b

- The Formation of the Marrow Bone in Chickens and Mammals and the Nature of Endochondral Ossification from a Historical Perspective.- Morph. Jb. 53 (1924a): 49-93

- August Rauber. His life and works.- Anat. Num. 58 (1924b): 129-138, 142-148, 170-174

- Outlines of scientific anatomy for students of biology and medicine, designed to supplement the usual textbook teaching, in Leipzig (G. Thieme) 1925, for use next to every anatomy textbook for students and doctors. - London (Bale) 1928. 400 pp.)

- (Comparative anatomy of the mastication muscles of the vertebrates. II. Part, end.) The mastication muscles of the Teleosteer.- Morph. Jb. 61 (1929): 49–220

- Alfred Brauchle: Outline of normal histology and microscopic anatomy.- Leipzig (G. Thieme) 1925, ed. by W. Lubosch. - 2nd improved. Ed. by W. Lubosch 1930.

- Investigations into the visceral muscles of the Sauropsiden.- Morph. Jahrb. 72 (1933): 584-666.

- Muscles and tendons - Leipzig (Akad. Verlagsges.) 1937

- General questions following my presentation of the visceral muscles in the Handbook of Comparative Anatomy of the Vertebrates (Volume V, 1938). Morph. Jb. 83 (1939): 163-174

Remarks

- ↑ data: Prof. U. Hoßfeld, pM; Katharina Kayßer: Johannes Sobotta (1869–1945) - life and work with special consideration of his time in Würzburg - Diss. Univ. Würzburg 2003. http://www.opus-bayern.de/uni-wuerzburg/volltexte/2004/928/pdf/DokarbKaysser_LS1_0Sig.prn.pdf ( Memento from October 23, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (p. 49). Place of death according to the German Biographical Encyclopedia.

- ↑ at the Königsstätter grammar school in 1893.

- ↑ Würzburg was the birthplace of Carl Gegenbaur , who made Jena the center of idealistic, d. H. had not made causally oriented morphology and which Lubosch emulated - he dedicated a warm life picture to him (1922b) - in 1912 Lubosch received the prosecution from Oskar Schultze - and the Carus Medal of the Leopoldina.

- ↑ He died while he was about to recuperate in the Schloss Horneck sanatorium , leaving behind his wife Else and a son (* 1912).

- ↑ Uwe Hoßfeld : From racial studies, racial hygiene and biological inheritance statistics to the synthetic theory of evolution: a sketch of the biosciences. In: Uwe Hoßfeld et al. (Hrsg.): "Combative Science" - Studies at the University of Jena in National Socialism. Weimar (Böhlau Verlag) 2003, pp. 519-574. Google Books

- ↑ Lubosch was, as they said at the time, a highly cultivated man. He also commented on philosophical (e.g. Schopenhauer's evolutionism) and aesthetic questions in magazines. When in 1905 the sample number of a medical and sexological journal was sent to him, he indignantly refused it - see p. http://www.horntip.com/html/books_&_MSS/1900s/1904-1922_anthropophyteia_(HCs)/1905_anthropophyteia_vol_02/

- ↑ Kornelia Grundmann: The Race Skull Collection of the Marburg Museum Anatomicum as an example for the craniology of the 19th century and its development up to the time of National Socialism. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 13, 1995, pp. 351-370; here: p. 351.

- ↑ cf. on the other hand, for example, Anton Johannes Waldeyer's dissertation "On the individual and racial anatomy of the human larynx" (1925) - Waldeyer studied in Würzburg, but he wrote and published this dissertation at Munich University and placed it in Würzburg, where he also received his doctorate (1927 ) another work on the histology of the aorta of sauropsids .

- ^ Rupert Riedl: The collapse of the morphology. Vienna (Seifert) 2006 (= The loss of morphology)

- ↑ Streptognathy is already mentioned by Meckel in 1833 as a certain mobility between the dentals and articulars of a number of fish (limited by the flexibility of Meckel's cartilage); They are now even known as real joints from several fish families. In this context, Lubosch believed to have discovered a completely new muscle, the "Musculus quadratomandibularis internus" , which, however, only represents a division of the intramandibular M. adductor mandibulae , Aω.

- ↑ It is well known that the genesis of the secondary temporomandibular joint in mammals has to be interpreted differently: Because of the enlargement of the brain, the dental ancestors came into contact with the skull on the side of the primary joint, not in front of it - the two joints then had a common axis, so that it was possible to dispense with the interior without mechanical problems.- It is always striking that Lubosch's neglect of the results of paleontological research is evident. See evolution of mammals

- ↑ In the assessment of Darwinism, Lubosch, coming from Gegenbaur's idealistic morphology, ultimately remained undecided. Lubosch (1931) could not and would not deny that Darwin had surpassed the “pure”, idealistic morphology with the selection.

- ↑ This can of course also be seen as a misinterpreted premonition of the chromosomal crossing-over within populations.

- ↑ This muscle portion is now known from a number of families of more primitive barnacles, whose relationship has not yet been clarified.

- ↑ s. about http://www.wfg-gk.de/glacialkosmos30.html

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lubosch, Wilhelm |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German anatomist (physician and zoologist) and morphologist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 28, 1875 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 16, 1938 |

| Place of death | Gundelsheim (Württemberg) |