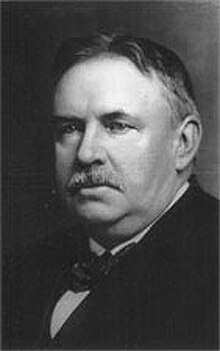

William Milligan Sloane

William Milligan Sloane (born November 12, 1850 in Richmond , Ohio , † September 12, 1928 in Princeton , New Jersey ) was an American philologist and historian . As a founding member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), he made a significant contribution to the revitalization of the modern Olympic Games through his efforts to spread the Olympic movement in the United States .

Adolescent years and vocational training

The son of James Renwick Wilson Sloane, a professor of theology in the American Presbyterian Church , William Milligan Sloane grew up in an upscale environment. In 1868 he completed his first degree in linguistics at Columbia College, Columbia University in New York City . The next four years to 1872, he taught classical languages at Newell Institute in Pittsburgh ( Pennsylvania ), a Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church, also held at the same time his father lectures.

At the age of 22 he went to Berlin , where he studied linguistics for classical and Semitic languages at the philological faculty of the Humboldt University . Theodor Mommsen and Johann Gustav Droysen were among his teaching professors . During this time he worked as a research assistant and private secretary for George Bancroft , envoy of the United States in Berlin and observer at the Reichsgericht in Leipzig . Here at the University of Leipzig concluded Sloane in 1876 his studies with a PhD doctor of letters from.

In 1877 he worked initially as an assistant professor of Latin, from 1883 as a professor of history at the College of New Jersey , now Princeton University . The reformed Anglo-American education system of that time was no longer based exclusively on traditional values, but included modern subjects from science, foreign languages and sport. So it was not surprising that Sloane, who did hardly any sport himself, took over the leadership of a sports committee (Faculty Committee of Outdoor Sports) in Princeton in 1884 .

Sloane and the Olympic Movement

Sloane, whose specialty was French history, made several trips to Europe , particularly to France , for his research and literary studies . In 1888 he stayed for several months in Paris , where he was a frequent guest of Hippolyte Taine , a French philosopher who aroused intellectual circles with his theories of the essence of man, supported by psychological studies of Napoléon Bonaparte . Even Pierre de Coubertin , founder of the modern Olympic Games, was acquainted with Taine. Sloane and Coubertin first met at a meeting at his home.

The common interest in educational issues and Coubertin's special interest in the Anglo-American education system formed the basis for their long-term relationships and later friendship. Sloane paved the way for Coubertin's first trip to the United States in 1889 by giving him access to major universities in the country and introducing him to politicians, including Theodore Roosevelt , who became President of the United States in 1901 .

Coubertin's second trip to the United States in 1893 was already influenced by the idea of reviving the Olympic Games. In Sloane he hoped to meet someone who supported his ideas. The cosmopolitan Sloane, always striving for an international exchange of ideas, enthusiastically accepted Coubertin's idea. He was convinced by the passion of his countrymen for the sport, and as if to prove he took Coubertin on Thanksgiving at a football game of the Ivy League with that in New York City between the university teams from Princeton and Yale was held. 25,000 spectators at Manhattan Field Stadium celebrated Princeton’s first win over Yale in over 10 years. Coubertin was so enthusiastic about the enthusiasm of the spectators and the subsequent celebrations with fireworks and parades that he spoke of a true scenery of the modern Olympic idea .

Sloane gave Coubertin the promise to take part in an international sports congress at the Sorbonne in Paris in 1894 , which would later go down in history as the first Olympic congress . There he took over the deputy chairmanship of the commission that dealt with the definition of amateur status . Sloane von Coubertin was also accepted as a founding member of the International Olympic Committee, which was actually founded on the last day of the Congress.

In the same year Sloane founded the American Honorary Committee for the Olympic Games in 1896 , a forerunner of today's National Olympic Committee of the United States, the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) , which has only had this name since 1961. He tried to get many universities and politicians to join the committee so that they could create a financial basis for sending as large a number of athletes as possible to the Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 . In reality, however, there was no funding and the participation of the 14 athletes who eventually took part in Athens was at great risk. The New York Times , which had a special donation account, wrote on March 18, 1896 that a generous friend of the college found themselves at the last minute and made the necessary donation to cover the high costs for the team. Although the name of the donor was not given, it was obviously Sloane, who had already bought tickets for his wife and himself, but neither of them were present in Athens.

According to the original regulations of the IOC, the presidency should be transferred to a member with the nationality of the country in which the upcoming Olympic Games would take place. For 1904, the Games were scheduled to be held in the United States, so Sloane was offered to succeed Coubertin at the 1901 IOC session in Paris. After the Games in Athens he had taken over the presidency from Demetrius Vikelas because the II. Olympic Games in 1900 took place in Paris. Sloane refused, however, and suggested that Coubertin be given the presidency permanently. Coubertin accepted on condition that he assumed the presidency for only 10 years.

Sloane's negative attitude was tactical. The IOC found itself in a crisis after a kind of competition to the IOC, the International Union for Olympic Games , was founded in the United States with the support of some foreign sports officials , under whose leadership the 1901 Olympic Games were to be held in Buffalo . Sloane feared that the US-American would not have the necessary distance to bring about an arbitration in the expected conflict. So Sloane remained a rather inconspicuous IOC member until 1925, the year in which Coubertin also resigned his presidency. However, his loyalty and friendship to Coubertin made him the strong man in the background.

Literary and professional life

Sloane's historical research and literary activity culminated in his four-volume edition Napoléon Bonaparte published in 1896, arguably the most complete and most autobiographical work on the life of the French Emperor. Together with other books on the French Revolution learned Sloane great recognition as a historian, he that as President of the "American Historical Society" (American Historical Association) was appointed and the leadership of the "American Academy of Arts and Letters" ( American Academy of Arts and Letters ) and in 1895, as co-editor of the American Historical Review, took over the leading article of this scientific journal, which still exists today.

His outstanding works include:

- Life and Work of James Renwick Wilson Sloane (1888)

- The French War and the Revolution (1893)

- The Life of Napoléon Bonaparte (4 volumes 1896; extended edition 1911)

- Life of James McCosh (1896)

- The French Revolution and Religious Reform (1901)

- Party Government in the United States of America (1914)

- The Balkans (1914)

In 1912 Sloane had returned to Berlin for a long time, where he lectured at Humboldt University as part of the Theodore Roosevelt Professorship of American History , an exchange program between the two universities established by Columbia University for university professors. During this time he supported Carl Diem in his preparations for the 1916 Olympic Games in Berlin, which fell victim to the First World War . He also had a lively exchange of views with Kaiser Wilhelm II to introduce him to the advantages of the American party system.

Sloane has received a number of awards and honors in his life.

- Peace Medal of the Association for International Conciliation

- Order of the French Legion of Honor

- Commander of Swedish North Star Order

- Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1913)

Individual evidence

- ↑ John A. Lucas: Early Olympic Antagonists: Pierre de Coubertin Versus James E. Sullivan. Stadium 3 (1977), 258-272.

- ↑ Arnd Krüger : Neo-Olympism between nationalism and internationalism, in: Horst Ueberhorst (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Leibesübungen , Vol. 3/1, Berlin: Bartels & Wernitz 1980, 522-568

- ^ William M. Sloane: History and Democracy. The American Historical Review. 1 (Oct., 1895), 1, pp. 1-23.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sloane, William Milligan |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American philologist and historian, founding member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 12, 1850 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Richmond , Ohio |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 12, 1928 |

| Place of death | Princeton , New Jersey |