Olympic Congress

The Olympic Congress is an assembly organized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) of personalities united in common action for the Olympic movement . The objective of the congress is to integrate the Olympic movement into the changing structure of society and to ensure the continued existence of the Olympic Games .

The first Olympic Congress took place from June 16 to 23, 1894 at the Sorbonne in Paris and is seen as the founding assembly of the IOC and the birth of the modern Olympic Games. The last Olympic Congress to date was held from October 3rd to 5th, 2009 in Copenhagen .

Development phases of the Olympic Congresses

To date, 13 Olympic Congresses have been held. With the exception of the founding congress, the following congresses can, without diminishing their respective importance, be divided into three development phases, which are based on their thematic focus and are staggered in time:

- Olympic Congresses from 1897 to 1913 , which served to consolidate the still new and strange idea of the Olympic Games and claimed the right to educational, psychological and medical aspects of sport to fathom and in the society to integrate.

- Olympic congresses from 1914 to 1930 , at which predominantly topics that were directly related to the program and the implementation of the Olympic Games came to the fore, and at which a number of important resolutions were passed, which in addition to administrative matters primarily the technical regulations and its implementation.

- Olympic congresses since 1973 , which were continued after an interruption of 43 years with a different objective. The congresses had lost their decision-making function. Each congress received a guiding principle that was directly related to the Olympic movement, which was presented and discussed. The role of an advisory forum was thus assigned to the Olympic Congress .

List of Olympic Congresses

| year | place | Main topic or motto | |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. | 1894 June 16-23 |

Paris | Definition of amateur status for athletes, resuscitation of the Olympic Games |

| II. | 1897 July 23rd to 31st |

Le Havre | Health, education, history, etc. issues related to physical fitness |

| III. | 1905 June 9-14 |

Brussels | Sports and physical education |

| IV. | 1906 May 23-25 |

Paris | Inclusion of the visual arts in the Olympic Games and in everyday life |

| V. | 1913 May 7-11 |

Lausanne | Psychology and Physiology of Sport |

| VI. | 1914 June 15-23 |

Paris | Standardization of the Olympic regulations and the conditions for the participants |

| VII. | 1921 June 2-7 |

Lausanne | Modification of the Olympic regulations and the conditions for the participants |

| VIII. | 1925 May 29 to June 4 |

Prague | Double congress: 1st Int. Olympic Pedagogical Congress, and Olympic Technical Congress |

| IX. | 1930 May 25-30 |

Berlin | Modification of the Olympic regulations |

| X. | 1973 September 30th to October 4th |

Varna |

Sport for a World of Peace Redefining the Olympic Movement and its future relationships between the IOC, international federations and the National Olympic Committees |

| XI. | 1981 September 23-28 |

Baden-Baden |

United by and for Sport The future of the Olympic Games and the Olympic Movement |

| XII. | 1994 August 29th to September 3rd |

Paris |

Centennial Olympic Congress, Congress of Unity Contribution of the Olympic Movement to Modern Society |

| XIII. | 2009 October 3rd to 5th |

Copenhagen |

The Role of the Olympic Movement in Society Olympism and Youth |

prehistory

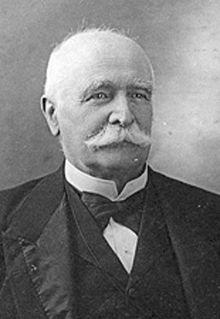

The Olympic Congress is closely linked to the Olympic movement, which the founder of the modern Olympic Games, Pierre de Coubertin , developed as a basic idea and spread throughout his life. Holding a congress was of particular importance to him as a suitable instrument for dissemination . With this he not only achieved public attention. He particularly hoped to arouse the interest of the invited, often high-ranking specialist audience.

First sports congress in 1889

Coubertin, who thought liberally and was interested in social issues, recognized a humiliated society and unstable political conditions in his home country France after the defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71 . As a pedagogue , he saw the causes in an outdated educational system. With determination he took the view that only a changed and completely redesigned upbringing could remedy the situation.

On the study trips to England undertaken since 1883 , Coubertin was impressed by the educational methods practiced there, the roots of which arose from the ideas and ideas of the pedagogue and theologian Thomas Arnold . The pupils of the public schools learned to be independent and responsible, mainly when doing sport in dealing with one another. From then on Coubertin was convinced of the educational and socializing effects of sport, which he tried to spread in his home country.

With the Comité pour la propagation des exercices physiques dans l'éducation (Committee for the Dissemination of Physical Exercises in Education) , which he founded in 1888 and led as General Secretary, Coubertin organized a Congrès des exercices physiques (Congress for physical exercises) in June 1889 . To better convey his ideas, sporting performances accompanied the congress. He chose the World Exhibition in Paris as the venue . Well-known personalities were invited.

The commitment with which Coubertin turned to the organization of this congress was indicative of later activities. The thoroughly successful course of the congress gave him the confidence to take this path for his future plans.

Origin of the Olympic Movement

The first sports congress organized by Coubertin did indeed get him the intended attention. The French Ministry of Education sent him to North America that same year , where he was supposed to get an impression of the educational system there in the United States and Canada . When visiting several universities, he was impressed by the sporting activities of the students. In November 1889 Coubertin was given the opportunity to give a lecture on his ideas about physical education at a sports convention in Boston .

After his return, Coubertin realized that educating young people to respect social relationships, to liberate mental readiness and to develop character through physical training should not be restricted to activities within the borders of his home country. He envisioned that an international competition with honorable intent could be a powerful stimulus for national identity and individual self-esteem. In this context, a passion that Coubertin had developed at a young age acquired new meaning: his enthusiasm for the history of antiquity . In particular, the ancient site of Olympia had awakened his longing. The ancient Olympic Games have always fascinated him.

Coubertin was certain that with advancing industrialization , through which science and culture of peoples were brought into a faster and better exchange, the time had now come to use the ideals of sport for international understanding. In addition, he saw these ideals threatened by the increasing professional practice of certain sports. He bundled all of these thoughts into a remarkable project, the restoration of the Olympic Games.

USFSA Jubilee Congress 1892

The Union des sociétés françaises de sports athlétiques (USFSA), founded in 1887, held a congress to mark its fifth anniversary in May 1892. One of the key speakers was Coubertin, who had been Secretary General of the USFSA since 1890. He recognized the opportunity that Congress offered him and called for the Olympic Games to be resurrected. Since John Astley Cooper had advocated the Pan-British Olympic Games (and with it the exclusion of France from these events) in London a year earlier and Astley Cooper committees had been founded all over the Anglo-Saxon world, he opposed the truly international Olympic Games . So that his appeal would be heard, he put his request at the service of peace among the peoples.

The message did not (yet) reach the congress participants. Coubertin saw the problem in the insufficient knowledge of the audience. Nonetheless, he remained determined and worked to seize the next opportunity that presented itself to him.

First Olympic Congress 1894

preparation

Coubertin took on a problem on which there were different points of view within the USFSA, namely the approach of an amateur in sport. At the time, this was a topic of fundamental importance for sports competitions, which was also of international interest. For Coubertin it was obvious to discuss and draft common and binding principles for this at a congress. The USFSA then decided to hold the Congrès international de Paris pour l'étude et la propagation des principes de l'amateurisme (Paris International Congress for the Study and Dissemination of Principles of Amateurism) in June 1894 . Even if the Congress is remembered today mainly because of the establishment of the Olympic Games, at that time a standardization of the amateur rules was an indispensable prerequisite for international sports traffic. The student rowers Coubertins were allowed to z. B. not take part in the English regatta in Henley , but the English students not in Hamburg, where the French were allowed to start. It was almost impossible for Australians to take part in competitions outside of their own country, as they were fed by the association during the long voyage and lost their amateur status due to the considerable monetary benefits.

Coubertin had cleverly had la possibilité du rétablissement des jeux olympiques (the possibility of reviving the Olympic Games) included as the last of eight items on the program . He was also appointed Secretary General of the USFSA to organize the Congress. This enabled him to have a not inconsiderable influence on the process, in which, according to his will, the main focus should be on the revival of the Olympic Games.

In support of his goals Coubertin made a trip to the United States in November 1893 and to London in February 1894 to secure the support of influential sports officials whom he had met on his previous trips. In January 1894, on behalf of the USFSA, he was already sending out invitations to congress to numerous national and international associations. In an accompanying circular he wrote, he saw the aim of the congress in the preparation of international understanding through the resurrection of the Olympic Games. In May 1894, the name Congrès international de Paris pour le rétablissement des jeux olympiques (International Congress of Paris for the Revitalization of the Olympic Games) finally appeared on the event schedule and the official invitations .

Congress participants

In order to attract the largest possible international number of participants, the Olympic Congress was held during the Paris race week (with the derby ). 78 delegates from 37 sports associations were sent to the actual congress . 58 of them were French and represented 24 sports clubs or organizations. The only 20 foreign delegates represented 13 sports associations and came from eight countries:

- United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland , 8 delegates

- Belgium , 4 delegates

- Sweden , 2 delegates

- Spain , 2 delegates

- Greece , 1 delegate

- Italy , 1 delegate

- Russia , 1 delegate

- United States , 1 delegate

What is striking here is that no representative from the German Reich was present. The Franco-Prussian War still weighed heavily on relations between the two countries. Large parts of the sports movement in Germany took a negative stance against the Olympic idea revived by a French. The mood in France was similar. The French sports associations, which in any case showed little interest in Coubertin's plans, threatened to withdraw if the German Reich were to participate. So it was obvious that Coubertin could not or would not contribute anything to relaxation.

Other participants in the congress in addition to the delegates mentioned were the 10 members of the organizing committee, among them Baron Alphonse Chodron de Courcel , from 1881 to 1886 French ambassador to the German Empire, who was given the presidency, and Coubertin as general commissioner of the organization. Sports journalist Frantz Reichel was an additional extraordinary member of the committee as a press representative.

Coubertin had drawn up a list of 50 honorary members for Congress. In addition to aristocrats, diplomats, parliamentarians and presidents of important sports associations, these included personalities from the international peace movement , such as Frédéric Passy , who was awarded the first Nobel Peace Prize in 1901 . It is unclear who of the honorary members was actually present. Independently of this, the personalities on this list testify to the considerable importance Coubertin wanted to attach to this congress. This list also shows that Coubertin, who attentively and with his own remarks followed the founding of the Interparliamentary Union in 1889 and the other, numerous activities of the peace movement in those years and maintained personal contacts, with the reintroduction of the Olympic Games not least also the goal of an international one Understanding and a peace between nations (paix des nations) intended.

procedure

The congress was opened on June 16, 1894 in the auditorium of the Sorbonne in Paris in front of an audience of nearly 2,000 with a speech by President Baron de Courcel. The central point of his speech was the call for the revival of the ancient ideal of balance between body and mind. This was followed by a solemn ceremony at which the Homeric Hymn to Apollon , composed by Gabriel Fauré , was premiered. Coubertin hoped from the undoubtedly pathetic mood that none of those present would deny the resurrection of the Olympic Games afterwards.

The second day, a Sunday, was reserved exclusively for some sporting performances. The sessions on the individual congress topics began on the third day of the congress, June 18, 1894. For this purpose, two commissions were formed which dealt with the two topics of the principles of amateurism and the revival of the Olympic Games . The former commission examined in several meetings the interpretation of the amateur status that had existed in the various sports associations and clubs. The different views contained a high potential for conflict and gave rise to critical debates. Amateurs practicing sports at that time were predominantly people of high social status . The Commission delegates found the rules of the influential English rowing association , the Amateur Rowing Association , to be discriminatory, according to which any worker who has ever used his hands to work cannot be considered an amateur. Accordingly, efforts were made to work out a definition that would overcome this class consciousness .

The Commission for the Olympic Games met under the chairmanship of the Paris-based Greek businessman Demetrius Vikelas , who attended the congress as a delegate of the Athens Panhellenic Society of Gymnastics . The commission had drawn up its proposals in just three meetings. Essentially, these were thoughts and suggestions from Coubertin that only had to be converted into workable resolutions. On the last day of the congress, all recommendations of both commissions were unanimously adopted in the final assembly of the plenary .

The Congress concluded on June 23, 1894 with a banquet in the Jardin d'Acclimatation , part of the Bois de Boulogne . On that occasion, some of those present were awarded the Ordre des Palmes Académiques , among them William Milligan Sloane , who was later appointed by Coubertin, representing the United States, to be a founding member of the International Olympic Committee.

Results

The congress succeeded for the first time in a consensual definition of the amateur athlete in coordination with national and international sports federations, which had the following wording (literal translation of the French original text):

- Those persons are regarded as amateur athletes who have neither participated in a competition open to everyone, nor in a competition for cash prizes or for money, from whatever source, even if it may be entry fee, or in competitions with professional athletes, and who have not participated in any Have received a salary as a physical exercise teacher or trainer throughout their lives.

In addition to this definition, regulations had been made that provided detailed information on eight points about the recognition and withdrawal of amateur status, the assessment of winning prizes and special cases.

The decisions of the Congress to reinstate the Olympic Games were described in seven points (verbatim translation of the original French text):

- There should be no doubt as to the benefits that the reintroduction of the Olympic Games will bring, either from an athletic point of view, or from a moral and international point of view, these Games should be reintroduced on the basis and in accordance with the conditions that meet the needs of modern times Correspond to life.

- With the exception of fencing, the Olympic competitions should only be organized for amateurs.

- The International Committee responsible for organizing the Olympic Games has to include a clause in its rules and regulations which gives it the right to exclude people from the competition who, through previous actions, could undermine the reputation of the institutions.

- No country has the right to be represented at the Olympics by anyone other than its own nationals, and qualifying competitions should be held in each country before the start of the Games in order to bring out the true champions in each sport.

- The following sports should, as far as possible, be carried out at the Olympic Games: athletics in the literal sense (running and competitions), water sports (rowing and sailing regattas, swimming), athletic games (soccer, lawn tennis, paume etc.), ice skating, fencing, Boxing, wrestling, equestrian sports, polo, shooting and gymnastics, cycling. In addition to athletics, a comprehensive championship called the Pentathlon (pentathlon) should be introduced. In addition, a price for mountaineering is to be awarded at the Olympic Games for the most important ascent since the previous Games.

- The Olympic Games are held for the first time in Athens in 1896 and for the second time in Paris in 1900 and then every four years in other cities around the world.

- If the Olympic Games cannot succeed without government support, the International Committee will take all necessary steps to obtain their official support from the authorities.

The decision to host the first Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 was made at the suggestion of Demetrius Vikelas, who was able to convince Pierre de Coubertin that his actual plan to hold it in Paris in 1900 was problematic due to the long waiting period of six years would.

The resolutions contained no statement regarding the modalities for the formation of the so-called Comité international (International Committee) . There are no other records of this either. Only the first edition of the Bulletin du Comité international des Jeux Olympiques , published one month after the congress, spoke of the establishment of the committee by the Congrès de Paris (Paris Congress) and contained a list of 13 members. These were chosen and named personally by Pierre de Coubertin. He justified this with a required elbow room for many conflicts that would inevitably arise.

Historical meaning

The Congrès de Paris , as the first Olympic Congress was initially called, was no doubt owed to the perseverance of Pierre de Coubertin. However, the public paid little heed to his ideas. The focus was less on the reintroduction of the Olympic Games and more on the agreement of a uniform definition of the amateur term. But even this was not binding on the national associations. The festivities in connection with the congress were the real highlights. They gave the event a framework that made attendees feel important without knowing what fundamental decisions they had made.

From today's perspective, the first Olympic Congress in 1894 is of fundamental importance to the history of sports. A sporting event has been created with the world's greatest attention and unprecedented continuity. Pierre de Coubertin's ideas about the Olympic Games were subject to social change over time, but his ideals continued with the Olympic movement. The subsequent congresses should also make their contribution to this.

Olympic Congresses from 1897 to 1913

After the successful first Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 , Pierre de Coubertin was confronted with a new strength awakened national pride of the Greeks, who called for the Games to be held in Greece all the time. This would mean that the recently created Olympic movement and the right to exist for the International Olympic Committee would already be at an end. At that moment it became clear how much Coubertin valued the importance of an Olympic Congress. He saw no other realistic means better suited to instantly give the International Olympic Committee an opportunity for self-affirmation and to display its outward-looking activity.

Coubertin, who had a decisive influence on the Olympic Congresses until 1930, used a congress as an effective tool to illustrate his ideas and to find active support for his plans in influential political and social circles.

II. Olympic Congress 1897

For the second Olympic Congress in 1897, Pierre de Coubertin had two goals in mind: the decisions made in 1894, in particular the venues for the Olympic Games, which change every four years, should not be called into question, and the activities of the International Olympic Committee should not be allowed to join deal with purely organizational and technical tasks in sport, rather one also has to deal with theoretical and educational questions.

With the outbreak of the Turkish-Greek War for Crete on February 15, 1897, the Greeks' demand for permanent Olympic Games in their country, which was well supported by personalities from international sports associations, became irrelevant before the opening of the Congress. Nevertheless, the decision to hold the second Olympic Games in Paris in 1900 at the Congress in 1894 was not yet secured. Resistance in one's own country and especially in the direction of the Paris World Exhibition in 1900 had to be overcome. Coubertin tried to exert influence by cleverly choosing the venue for the congress. Le Havre was the residence of the then French President Félix Faure , who also spent the summer months there. Coubertin, who himself took over the presidency of the congress, was also able to win Faure as patron . This alone drew enough attention to the Congress that the Olympic Movement could be consolidated without further addressing the resolutions of 1894 and the legitimacy of the International Olympic Committee was reinforced.

The Olympic Congress thus primarily dealt with the educational and health aspects of sport. However, the resolutions drawn up on this did not bring any significant progress. There was even disagreement among the few IOC members present. Critical voices said that Coubertin's discussion of physical fitness as one of the educational foundations would not affect the questions of the Olympic movement. Coubertin showed himself to be consistent in this regard, however, and always left this topic a wide scope at the following Olympic Congresses.

III. Olympic Congress 1905

The second Olympic Games in Paris in 1900 were extremely disorganized. The reason for this was also the lack of uniform rules and evaluation criteria for the games. Individual members of the International Olympic Committee therefore called for a congress to introduce uniform standards and a sports code . Coubertin took advantage of the visit of the Belgian King Leopold II in 1901 to Paris, whom he was able to convince to hold an Olympic congress in Brussels in 1903 and to take over the patronage.

Coubertin was of the opinion that rules for the Olympic Games should not be decided authoritatively by the IOC, but that the task at best would be to harmonize and merge existing rules. To do this, it was necessary to use a questionnaire to research the different customs of the various sports associations in several countries. The response was disappointing. After the congress had to be postponed to the year 1905 for organizational reasons and the third Olympic Games had already taken place in St. Louis in 1904 , Coubertin saw the topic as obsolete. So he seized the opportunity to give the congress a thematic twist and put it under the motto of sport and physical education , the central concern of Coubertin. The result of the congress were numerous recommendations for the introduction of sport into society.

At an IOC meeting during the congress, Coubertin had to submit to an unpopular matter. At this meeting he tried to overturn an earlier decision of the IOC, according to which the IOC had approved the hosting of the Olympic Intermediate Games in Athens, which had been decided by decree in Greece . Coubertin was faced with allegations, which had the bad organization of the games in 1900 in Paris and 1904 in St. Louis. His position was so weakened that he had to accept the games in Athens.

IV. Olympic Congress 1906

The 1906 Olympic Congress held at the Comédie-Française in Paris dealt with a matter close to Coubertin's heart, the integration of the fine arts into the Olympic Games. In his mind, architecture , sculpture , painting , literature and music were essential to restore the Olympic Games to their original beauty. Suggestions were made as to how this could best be implemented and how the various works should be assessed and recognized. In fact, from 1912 to 1948, art competitions were held at the Olympic Games based on proposals from Congress.

The date of the congress offers plenty of scope for speculation, as it took place just a few weeks after Coubertin's unintentional interludes in 1906 in Athens, which are still not officially recognized by the IOC. At least it can be said that Coubertin was able to use the date of the congress to offer an excuse why he was not present in Athens. In contrast, the majority of IOC members considered the Congress to be of secondary importance, focusing on the Athens Games.

V. Olympic Congress 1913

The 1913 Olympic Congress in Lausanne was again dominated by theories of sports psychology and educational theory by their most ardent advocate, Pierre de Coubertin. Years before, he recognized developments in sport that were of little help to his original concern. The pursuit of steadily increasing physical performance, which was reinforced by two successful Olympic Games in 1908 and 1912 , aroused criticism from educators, psychologists and medical professionals. According to Coubertin, the congress was supposed to bring about an exchange of the opinions of these experts, which gave sport in general the right to a scientific debate. As with other events, Coubertin also added value to the congress by not being present. B. Former American President Theodore Roosevelt , who gave a positive written statement. Coubertin later described the Olympic Congress in Lausanne as the birth of the psychology of sport .

The conference venue Lausanne was chosen by Coubertin with a special motive. According to Coubertin, the international importance of the city was underestimated. The location offers every imaginable opportunity for sport. The university with its unusual architecture exudes freshness and splendor of the youth and has an honorable position in the academic world, even without playing a leading role. For Coubertin the ideal place for the construction of the administrative headquarters of the Olympic movement. Hosting an Olympic Congress was the first step on the way there.

Olympic Congresses from 1914 to 1930

A discussion of the standards and rules for the Olympic Games was planned for the 1905 Congress, but this failed due to the lack of interest from national sports associations. With the end of the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm , however, their attitude changed. In the meantime, 32 National Olympic Committees had also been founded and the number of national and international sports associations was steadily increasing. In preparation for the 1916 Summer Olympics in Berlin , the IOC therefore saw the need to deal with these issues at the anniversary congress planned for 1914.

This thematic orientation, which differed fundamentally from the previous congresses, was to determine the Olympic congresses until 1930. This development was not necessarily in Coubertin's interest, but he could no longer avert it. As a result, he slowly withdrew from work that could no longer be reconciled with his original ideas of the Olympic concept.

VI. Olympic Congress 1914

The decision to hold an Olympic Congress to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Olympic movement was already taken at an IOC meeting in 1911. The congress was to take place on the anniversary of the First Olympic Congress of 1894 and at the same location, the Sorbonne in Paris. A separate committee was formed for the program and organization. Numerous festivities created a festive atmosphere. The highlight of this was the presentation of the motif of the Olympic rings . Specially designed for this celebration, they were presented to the guests in a ceremony on a flag with a white background. This was the baptism of the most important symbol of the Olympic Games up to the present day.

The main task of the working sessions was to define a sports program for the Olympic Games. The 32 National Olympic Committees now in existence and a large number of international professional associations demanded a say in this matter, which the IOC could not ignore if it did not want to lose its leadership position. The result of this was that the various proposals of the NOC and the professional associations could not be rejected without further ado and that a large number of sports had to be included in the program of the Olympic Games. These were divided into compulsory and optional sports. As a result, criticism of this program grew louder.

Another issue was the participation of women in the Olympic Games. Coubertin was an advocate of the ancient tradition that held the Olympic Games as a recurring ceremony of male athleticism that was rewarded with applause from the ladies. At the congress there had previously been a fundamental decision that in the medal table, which was still official at the time, the medals of women should have the same value as those of men. Here Coubertin (together with the USA) already belonged to the outvoted minority. He was reassured (he was ready to resign), since the selection of the disciplines would be left to the respective international professional associations, which decided according to their tradition. In Coubertin's interventions in this regard, however, he was overruled several times. In the official report to the congress published by Coubertin in 1919, only the sports swimming and tennis had been included as competitions open to women because he chaired the meeting and wrote the minutes. However, the Australian sports newspaper Referee reported extensively on the Congress every day. The congress officially ended on June 23, 1914. This was followed by five days of further festivities for the congress participants in Reims . The last day, June 28, 1914, was the day of the assassination attempt in Sarajevo . The following First World War brought the Olympic movement to a temporary standstill. Minutes of the 1914 Congress were never published. It was not until 1919, at the first IOC meeting after the war, that the resolutions of the Congress were taken up again, some points were revised and published.

VII Olympic Congress 1921

In 1915 the headquarters of the IOC had been relocated to Lausanne, and understandably the first congress took place here after this change. It was supposed to pick up where one had to stop in 1914. For the numerous and varied questions that were raised not least by the Olympic Games in Antwerp in 1920 , recommendations had to be drawn up in three preparatory conferences. The meanwhile 19 international sports associations , whose importance was steadily increasing, saw their participation in this as too little. Their participation in Congress was necessary to strengthen the Olympic movement, which was seen to be threatened by a wave of games of a patriotic and religious character.

The original task of the congress was to work out a clearly structured and reduced program for the Olympic Games. The international sports federations, however, claimed for their part to determine the competitions to be held themselves. So it was not surprising that there were hardly any changes to the existing program.

The congress also dealt with the integration of winter sports into the Olympic Games. As early as 1908 there was figure skating at the Olympic Games and in 1920 there were also Olympic ice hockey tournaments for the first time . As early as 1911, at an IOC meeting, the first proposals were made to integrate the Nordic Games , which had been held in Scandinavia since 1901, into the program of the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm. This met with strong opposition from the Swedish organizers. At the congress, the French finally submitted a proposal to hold an IOC-supported winter sports week in Chamonix in 1924 . The motion met with approval, as it could reduce the Scandinavian countries' sole entitlement to games of this kind. It was only two years later that the IOC officially confirmed these games as the first Olympic Winter Games .

Looking back on the only recently ended First World War, Coubertin had also planned an exchange of ideas for the Congress on the advantages of sport in overcoming social barriers and creating social peace. The absolute restriction to technical and administrative questions about the Olympic Games, which could not be avoided through the involvement of the international sports associations, had now, however, completely led to a turning away from Coubertin's preferred discussion of educational content at the Olympic Congresses.

VIII Olympic Congress 1925

In 1925 an earlier demand was met for the first time to hold the Olympic Congress in regular succession, if possible one year after the Olympic Games. It was also now regulated that the convening of a congress and the setting of the agenda could only be carried out by the IOC.

One day before the start of the Congress, the new IOC President Henri de Baillet-Latour was elected . Pierre de Coubertin had announced his retirement after 39 years in this office. The congress was intended to provide a worthy setting for Coubertin's farewell. The congress location Prague was made for this, because Coubertin has always had a particular fondness for this city. Jiří Guth , Coubertin's only remaining companion from the founding years of the Olympic movement, took over the organization.

For the first time a double congress was held, a technical Olympic congress and an educational Olympic congress, which met independently of each other. The Pedagogical Congress was also a recognition of the work of Coubertin, who was particularly committed to this topic throughout his life. He was accordingly committed, developed proposals for the program and took an active part in the meetings. The Pedagogical Congress received little attention even among the delegates and the resolutions passed had no practical impact. Coubertin was understandably deeply disappointed about this.

The Technical Congress, in which the NOC and international sports associations were now firmly integrated, continued the content of the two previous congresses. This time the focus was on the problem of the amateur term. The international sports federations claimed a definition of their own amateur rules. The conflicts led to a compromise, according to which the international associations enforced their claim, but had to accept minimal preconditions from the IOC for an amateur to participate in the Olympic Games. This also meant that a participant was not allowed to receive reimbursement for loss of earnings while participating in the Olympic Games. There were numerous detailed debates on issues for which the Olympic Congress was not the appropriate place. Nevertheless, they were held so as not to put any further strain on the already tense relationship between the IOC and international sports associations.

IX. Olympic Congress 1930

Relations between the IOC and international sports federations were at a low point at the time of the 1928 Summer Olympics in Amsterdam . The reason for this was the different definitions for and ideas about an amateur athlete. In particular, the financial expense allowance practiced by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) contributed to the fact that this should be discussed again at an Olympic Congress that was convened in Berlin in 1930 . However, the debates did not result in any changes in the IOC's position on amateur status. The problem was passed on to the newly established Permanent Council of Delegates of the International Olympic Federations (permanent council of the delegates of the international sports federations of Olympic sports) . This advice was a concession by the IOC to the associations so that the Olympic Congresses, freed from conflict, could devote themselves to the elementary tasks of spreading the Olympic movement.

Nevertheless, some organizational issues were also dealt with at the congress. So one dealt again with the Olympic sports program, which was changed slightly. The number of participants in individual competitions was also limited. Most of the resolutions, however, were of minor importance.

The congress was of particular importance for Berlin and the German Reich. Efforts were made to give the participants a positive impression, because Berlin had applied for the 1936 Summer Olympics . The festive accompanying program included excursions, visits to the opera, receptions and numerous gala dinners. All conference participants were given an application. In 1931 Berlin was finally awarded the contract for the 1936 Games by the IOC.

Olympic Congresses since 1973

The Council of Delegates, founded in 1930, simplified the work between the IOC and international sports associations considerably, so that there was initially no demand for an Olympic Congress. Even before the outbreak of the Second World War, discussions were held about holding a congress to be held in Riga . The war prevented these plans.

In the first years after the war, the IOC continued its activities unabated to revitalize the Olympic movement and the Olympic Games. A wide variety of commissions were formed and regular meetings were held with various sports organizations. The Olympic Congress had served its purpose as a communication organ and the article contained specifically for this purpose in the Olympic Charter was even removed for a time.

With the election of Avery Brundage as IOC President in 1952, the fronts hardened. The meetings turned out to be increasingly difficult, also because Brundage saw the IOC as the only institution responsible for Olympic sport. Brundage vehemently opposed calls by the NOC and international sports associations to enable their representatives to become members of the IOC. After a long period of dissonance and a hardening of the fronts, in 1968 the Olympic Congress was used as an instrument in order to re-establish contacts out of responsibility towards society.

Xth Olympic Congress 1973

The congress originally planned for 1971 in Sofia was postponed to 1973 for reasons of better preparation, the congress location moved from the Bulgarian capital to Varna . The new date made it possible to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the Bulgarian National Olympic Committee during the congress. Avery Brundage, who was always skeptical about a resumption of the Olympic Congress, had meanwhile handed over the presidency of the IOC to Lord Killanin . Killanin had previously been President of the Tripartite Commission , which brought together representatives from the IOC, the NOC and international sports federations, and was set up in preparation for the Olympic Congress. As a result, Killanin had a much more open-minded attitude towards cooperation between the IOC and other sports organizations.

The relationship between the IOC, NOC and international sports federations was only one of the important issues. The serious social and political changes since the last congress led to completely new questions that dealt with the rights of women in sport, the doping problem, the gigantism of the games and again with the amateur status. As a result, the Congress produced countless speeches and short presentations with a wealth of suggestions. Discussions and votes were not planned, however, especially since the decision was made in preparation for the congress that no more specific resolutions should be passed.

The results of the Congress have been summarized in two statements. That of the delegates comprised specific recommendations, such as the maintenance of the Tripartite Commission as a permanent body for cooperation, the admission and inclusion of women in all national and international sports organizations and an improvement in relations with the athletes. For the first time ten Olympic champions were invited as observers to the congress in Varna, but they did not have the right to speak. The second declaration by IOC President Killanin was a call to all athletes in the world to instill the spirit and principles of peaceful games among the world's youth when they participate in the Olympic Games, so that the international trust and benevolence practiced in this way lead to peace in the world could.

Increasing political influence on sport became apparent at the congress. Numerous delegates from countries of the Eastern Bloc and the Third World were high-ranking politicians. Her speeches often contained one-sided agitation on sports politics. However, there was no direct confrontation with the IOC, partly because the Soviet delegation in Varna expressed the wish to host the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow .

XI. Olympic Congress 1981

The Olympic Congress held in the Baden-Württemberg spa town of Baden-Baden in 1981 was the result of a resolution to hold regular congresses every eight years. However, it remained the only Congress that actually complied with this regulation.

The congress took place in an environment of extreme political tension, which also had serious effects on sport and the Olympic Games. The Olympic boycotts of 1976 and 1980 led the Olympic movement to the edge of its existence. The IOC President Killanin, who acted discouraged in this crisis, was replaced in 1980 by Juan Antonio Samaranch . He tried to explain to leading sports officials on the one hand and politicians on the other that the influence of politics on sport would be the end of the Olympic Games and, moreover, the end of all international sporting relations. The IOC made it very clear that the invitations sent out for the Olympic Congress only served the purpose of dealing intensively with the affairs of sport and athletes. The motto of the congress United by and for Sport clearly expressed this.

Those who doubted the success of the congress were taught otherwise. The multitude of topics relevant to the future of the Olympic Games and the Olympic Movement led to a wealth of views, despite a tight program that often allowed delegates only five minutes to speak. All those involved succeeded in defining clear and uniform recommendations, which subsequently led to significant decisions, such as the formation of an athletes' commission or the admission of the first two women, Pirjo Häggman from Finland and Flor Isara Fonesca from Venezuela , to the IOC.

Another reason for the success of the congress is the inclusion of radio, television and print media as almost equal partners within the Olympic family . The direct broadcast of the opening ceremony on television and the observer status of all media contributed to attracting a broad public to the congress for the first time and conveying the content to them. This also laid the foundation for the public marketing of the Olympic Games. As a consequence, the amateur rules were largely abolished.

XII. Olympic Congress 1994

The IOC revoked the eight-year rhythm for Olympic congresses, which had only been adopted in 1973, when the congress scheduled for 1990 in Tokyo was canceled. Attention was drawn to 1994, the year of the 100th anniversary of the International Olympic Committee. The Congress of the Century took place in Paris, where he was born, accompanied by numerous festivities. An Olympic flame, lit especially at a historical site in Olympia , was carried by a team of prominent athletes from the Eiffel Tower , past the Sorbonne, the conference location from 1894, to the new conference location Palais Omnisports in Bercy . A sport climber descended from the Eiffel Tower with the Olympic flag. Furthermore, several sporting events and exhibitions accompanied the congress.

The three elementary organizations of the Olympic movement (IOC, NOC and international sports federations) were not only responsible for discussing the topics of the congress; representatives of radio, television and print media were given responsibility for a separate topic under the guiding principle of sport and the mass media . The IOC saw in this direct involvement a consistent continuation of the connection between the Olympic movement and its dissemination through the press, which had existed since the founding congress. Pierre de Coubertin was an avid writer and enthusiastic writer.

From the multitude of topics, one thing stood out in particular: sport and the environment . It became clear that the environmental protection that everyone is talking about could not be excluded from sport. Only an intact nature can offer those who do sports, like everyone else, the basis for a healthy and carefree life. Therefore it is necessary that sport takes responsibility for the environment through its actions. To anchor this attitude, environmental protection was declared a basic goal of the Olympic movement and was included in the Olympic Charter.

XIII. Olympic Congress 2009

The congresses of 1981 and 1994 had already led to an expanding cooperation between the IOC and the mass media . With the increasing importance and spread of the internet since the congress in Paris over the past 15 years , it was in the nature of things that a new congress had to deal with this topic.

For 115 years it has been the task of the Olympic Congress to spread, shape and shape the idea of the Olympic movement created by Pierre de Coubertin. In 2009, the Internet made it possible for the general public to participate in this process for the first time. A virtual Olympic Congress gave every Internet user the opportunity to speak and debate the topics planned for the congress on an Internet platform provided by the IOC between October 2007 and February 2009. The contributions were evaluated and incorporated into the discussion basis of the Olympic Congress.

The actual topics of the congress did not differ significantly from those of the previous congresses. The focus was primarily on their orientation and further development for the society of the new millennium. The flood of recommendations, summarized in 66 points of the final report, were passed on to the various commissions, committees and expert bodies. From this, they develop quorum facts that lead to concrete decisions primarily at the IOC sessions.

Milestones in the history of the Congress

- I. Congress 1894

- Establishment of the International Olympic Committee (IOC)

- Decision on the resurrection of the Olympic Games

- First standardization of the definition of an amateur athlete.

- II Congress 1897

- Confirmation of the International Olympic Committee as the lead organization for the holding of the Olympic Games

- Decision on the holding of regular meetings every year, which subsequently represent the highest body of the IOC from a legal point of view as an IOC session

- IV Congress 1906

- Introduction of art competitions at the Olympic Games

- 5th Congress 1913

- Naming of the city of Lausanne , located on the Swiss shore of Lake Geneva , the conference venue, with the intention of establishing the administrative headquarters of the IOC and the center of the Olympic movement here in the future.

- VI. Congress 1914

- First definition of the sports, separated according to mandatory and optional competitions, which are to comprise the program of the Olympic Games.

- Presentation of the motif of the Olympic rings in connection with the Olympic flag as a symbol of the Olympic Games.

- VII Congress 1921

- First participation of international sports associations with voting rights at the congress

- Decision on the first introduction of winter sports weeks in 1924 under the supervision of the IOC, which were later legitimized as the Olympic Winter Games

- VIII Congress 1925

- Introduction of regular independent Olympic Winter Games

- The duration of the Olympic Games was set at two weeks including three Sundays.

- IX. Congress 1930

- Establishment of a permanent council of delegates from the international sports federations of Olympic sports

- X Congress 1973

- Setting up a standing commission for the IOC to work with the NOC and international sports federations

- First participation of athletes in the Olympic Congress with observer status

- XI. Congress 1981

- Appointment of the first women as IOC members

- Establishment of an athletes commission

- Inclusion of radio, television and print media in Congress as official observers

- XII. 1994 Congress

- The protection of the environment was declared a further basic goal of the Olympic movement and was included in the Olympic Charter

- XIII. Congress 2009

- First direct involvement of the public and the inclusion of modern digital media by holding a Virtual Olympic Congress , the results of which served as an additional basis for discussion at the Olympic Congress

Structure of the modern Olympic Congress

The IOC has recorded the subject of the Olympic Congress in the Olympic Charter, Chapter 1, Rule 4, and has drawn up three articles for this rule, which the committee is obliged to observe within the framework of its own legal system. However, these essentially only include the administrative matters of the Congress.

Convocation

The first article in Rule 4 of the Olympic Charter deals with convening (verbatim translation of the original English text):

- The Olympic Congress is convened by the President by resolution of the IOC session and organized by the IOC at a location and on a date determined by the IOC session. The President chairs the meeting and determines the procedure.

This stipulates that the Olympic Congress is not an event that recurs at regular intervals. At the congresses of the early years, various attempts were made to give the congress a certain degree of continuity. The current regulation, however, gives the Congress a special meaning, because it is only convened when necessary, whereby the circumstances for this are solely subject to the assessment of all IOC members.

composition

The second article on rule 4 of the Olympic Charter deals with the composition (verbatim translation of the original English text):

- The following will take part in the Olympic Congress: Members, honorary presidents, honorary members and external honorary members of the IOC, delegates representing the international sports federations and the NOC, including representatives of organizations recognized by the IOC. In addition, take part in the Olympic Congress: athletes and personalities who are invited because of their individual or representative performance.

The number of official participants in the Olympic Congresses has increased considerably as a result of the regulation. In 2009, 1249 people attended the congress. By comparison, there were only about 60 participants at the 1897 Congress. This comparison does not diminish the importance of the respective congress, but rather reflects the social status of the Olympic movement over time. The participation of personalities from different groups also illustrates their meanwhile equal position within the Olympic family .

Program and organization

The third article in Rule 4 of the Olympic Charter deals with the program (verbatim translation of the original English text):

- The IOC Executive Board sets the agenda for the Olympic Congress in consultation with the international sports federations and the NOC.

In contrast to the early years of the Olympic Congresses, the program is no longer exclusively determined by the IOC. For the congresses in the period between the two world wars, the international sports federations and NOC asserted their claims to play a decisive role in determining the topics to be dealt with. Ever since these organizations were incorporated into the Olympic movement through the Olympic Charter (Chapters 3 and 4), they have even been obliged to support the Olympic movement.

The IOC forms various commissions and committees for all administrative tasks related to the implementation of the congress and draws up appropriate regulations. These also contain a precisely planned schedule of the congress.

procedure

The process is not subject to any special regulation. It corresponds to the practice of a normal congress that begins with an opening event. The opening speech will be given by the IOC President, followed by speeches from special invited guests.

The topics on the agenda are discussed within a given time frame in plenary sessions with simultaneous translation. The discussion of the individual topics assigned to each topic begins with the presentation by the speakers of the committee formed for this purpose. The moderator of the respective committee is then responsible for ensuring that all participants are given the opportunity to give their opinion on the topics in the subsequent discussion.

The congress ends with a closing event, at which the IOC president usually gives an acceptance speech. The opening and closing events are usually framed by numerous artistic performances. Actions accompanying the congress are intended to bring the content of the Olympic movement closer to the public.

An official final report summarizes the procedure and recommendations of the congress. It forms the basis of the further work of the IOC and its affiliated institutions.

Goal setting

Some excerpts from the welcoming speech given by IOC President Jacques Rogge at the opening event at the 2009 Olympic Congress in Copenhagen clearly illustrate the objectives of the Olympic Congress (literal translation of the original English text):

- We are here to share ideas on ways to maintain and strengthen our movement and Olympic values in this new millennium. The overarching theme of the congress is "The Olympic Movement and Society". ... We use the joy of sport to promote physical and mental health and to spread the universal values of mutual understanding and peace, solidarity, advantages, friendship, respect and fair play. … We have a special obligation to put our values into practice on behalf of athletes and young people - athletes because they are the heart of our movement, young people because they are our future. ... It is now up to us to look to the future. We are here to ensure that the Olympic movement continues to nurture athletes, the world's youth, and society as a whole for decades to come.

The remarks made it clear that the Olympic Congress has a rather profound task. The interim importance as an administrative organ has been completely given up. The orientation is based on the former Coubertinian values, which are subject to different conditions over time. As a result, the Olympic Congress will continue to be used in the spirit of Pierre de Coubertin as an organ to spread the Olympic ideals.

See also

literature

- Norbert Müller: One Hundred Years of Olympic Congresses 1894-1994 . Ed .: International Olympic Committee. Schors Verlag, Niedernhausen 1994, ISBN 3-88500-119-5 , p. 224 .

- Pierre de Coubertin : Olympic memories . Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-548-35612-5 , pp. 237 .

- Karl Lennartz : The Olympic Games in Athens 1896, explanatory volume . AGON Sportverlag, Kassel 1996, ISBN 3-928562-91-6 , p. 170 .

- Karl Lennartz, Walter Teutenberg: II. Olympic Games 1900 in Paris. Presentation and sources. AGON Sportverlag, Kassel 1995, ISBN 3-928562-20-7 , p. 238.

- International Olympic Committee (Ed.): XIII Olympic Congress - Proceedings . Lautrelabo S.à rl, Belmont-sur-Lausanne, Switzerland 2010, ISBN 92-9149-132-2 , p. 255 (English).

Web links

- International Olympic Committee (English)

- Videos and texts of the speeches and recommendations of the XIII. Olympic Congress 2009 (English)

- Historical digital sports archive (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ founding congress. (No longer available online.) Olympic Museum, 2010, archived from the original on November 14, 2009 ; accessed on September 10, 2010 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Olympic Charter. (PDF; 2.6 MB) International Olympic Committee, 2010, accessed on September 9, 2010 (English).

- ^ Yves Pierre Boulogne: La vie l'oeuvre pédagogique de Pierre de Coubertin , Ottawa 1975, p. 15 (French)

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Pierre de Coubertin (translated and edited by Bernd Wirkus): Twenty-one years of sports campaigns (1887–1908) . Aloys Henn Verlag, Ratingen 1974, ISBN 3-450-02000-5 , pp. 194 .

- ↑ Pierre de Coubertin: L'Éducation en Angleterre , Hachette, Paris, 1888, 327 pages (French)

- ↑ Pierre de Coubertin in Revue Olympique, 1914, No. 97, pp. 4–8: Un congrès oublié. (PDF; 128 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, accessed on September 10, 2010 (French).

- ^ Isabel Barrows: Physical Training. A Full Report of the Papers and Discussions of the Conference held in Boston in November 1889. , Press of George H. Ellis, Boston, 1890 (English)

- ↑ Carl Diem : The Olympic thought - speeches and essays , Carl Hoffmann, Schorndorf, 1967, 133 pages

- ^ Arnd Krüger : The role of the amateur question at the Olympic Congress 1894, in: Sportzeiten 4 (2004), 2, 49 - 68.

- ^ A b c Karl Lennartz : The Olympic Games in Athens in 1896, explanatory volume . AGON Sportverlag, Kassel 1996, ISBN 3-928562-91-6 , p. 170 (illustration on page 36).

- ↑ Arnd Krüger: Nothing Succeeds like Success . The Context of the 1894 Athletic Congress and the Foundation of the IOC, in: Stadion 29 (2003), 47-64.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Pierre de Coubertin: Mémoires Olympique , Bureau International de Pédagogie Sportive, Lausanne, 1932, 218 pages (French)

- ↑ Dietrich Quanz in OLYMPIKA: The International Journal of Olympic Studies Volume II, 1993, pp. 1-23: Civic Pacifism and Sports-Based Internationalism. (PDF; 84 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, accessed on September 10, 2010 (English).

- ↑ Pierre de Coubertin: L'Éducation de la Paix , in La Réforme sociale, 2e série, tombe VII, September 16, 1889, pages 361–363 (French)

- ↑ Dietrich Quanz in Citius, Altius, Fortius - Journal of Olympic History, Vol.3, No.1, pp. 6-16: Formatting Power of the IOC Founding. (PDF; 49 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, accessed on September 9, 2010 (English).

- ↑ a b c d Norbert Müller: One Hundred Years of Olympic Congress 1894-1994 . Schors Verlag, Niedernhausen 1994, p. 224 .

- ↑ a b c Pierre de Coubertin in Revue Olympique, 1894, No. 1, pp. 3-4: Les Travaux du Congrès. (PDF; 314 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, accessed on September 13, 2010 (French).

- ↑ Pierre de Coubertin in Revue Olympique, 1894, No. 1, pp. 1-4: Bulletin du Comité international des Jeux Olympiques. (PDF; 314 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, p. 4 , accessed on September 13, 2010 (French).

- ^ IOC, Congrès International de Sport et d'Éducation physique , Auxerre, 1905, 249 pages (French)

- ↑ Arnd Krüger: Neo-Olympism between nationalism and internationalism, in: Horst Ueberhorst (Hrsg.): Geschichte der Leibesübungen , Vol. 3/1, Berlin: Bartels & Wernitz 1980, 522-568.

- ^ Norbert Müller in Olympic Review, 1997, Vol.26, No.16, pp. 49-59: The Olympic Congress in Lausanne. (PDF; 1.0 MB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, p. 10 , accessed on September 14, 2010 (English).

- ↑ Revue Olympique, 1913, No.8, pp. 119–120: L'emblème et le drapeau de 1914. (PDF; 129 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, p. 2 , Retrieved September 16, 2010 (French).

- ^ Revue Olympique, 1914, No.7, pp. 100–110: Les fêtes olympiques de Paris. (PDF; 185 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, p. 11 , accessed on September 16, 2010 (French).

- ↑ Pierre de Coubertin in Revue Olympique, 1912, No. 79, pp. 109–111: Les femmes aux Jeux Olympiques. (PDF; 220 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, accessed on September 10, 2010 (French).

- ↑ Ana Maria Miragaya in Revue Olympique, 1912, No. 79, pp 109-111: The process of inclusion of women in the Olympic Games. (PDF; 2.1 MB) Library Network of Western Switzerland, 2009, accessed on September 18, 2010 (English).

- ↑ a b IOC: Congrès des Comités Olympiques Nationaux tenu à Paris Juin 1914 , Lausanne 1919, 9 pages (French)

- ↑ Arnd Krüger: The 6th IOC Congress of 1914, in: E. BERTKE, H. KUHN & K. LENNARTZ (eds.): Olympically moved. Festschrift for the 60th birthday of Prof. Dr. Manfred Lammer . Cologne: DSHS 2003, 135 - 144.

- ↑ Revue Olympique, 1914, No.7, pp. 110–111: Les fêtes olympiques de Reims. (PDF; 185 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2009, p. 2 , accessed on September 16, 2010 (French).

- ^ Otto Schantz: The Olympic Ideal and the Winter Games. (PDF; 243 kB) (No longer available online.) Le Comité International Pierre de Coubertin - CIPC, 2006, p. 19 , archived from the original on May 5, 2013 ; accessed on September 20, 2010 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Henri de Baillet-Latour in Official Bulletin of the International Olympic Committee, 1926, No.1, pp. 15-17: Decisions taken by the Technical Congress at Prague. (PDF; 128 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 21, 2010 (English).

- ↑ Bulletin of the International Olympic Committee, 1930, No.16, pp. 17-20: Meeting of the IOC (PDF; 98 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 22 2010 (English).

- ↑ Bulletin of the International Olympic Committee, 1930, No.16, pp. 20-24: Olympic Congress of Berlin. (PDF; 101 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 22, 2010 (English).

- ^ Karl Wilhelm von Drigalski: Berlin. The sports capital of Germany. Dedicated to the 1930 Olympic Congress. , Berlin 1930, p. 44.

- ↑ Aija Erta in Journal of Olympic History, 1930, Vol.7, No.1, pp. 36-37: Mr. Janis Dikmanis. (PDF; 118 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 23, 2010 (English).

- ^ A b IOC Newsletter, 1968, No.15: Extract of the 67th Session. (PDF; 103 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 23, 2010 (English).

- ↑ a b Olympic Review, 1978, No. 125, pp. 161-166: Statement from the Tripartite Commission. (PDF; 39 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 24, 2010 (English).

- ↑ International Olympic Committee: 10th Olympic Congress. Official Report , Lausanne 1974, 171 pages (English and French)

- ↑ Olympic Review, 1981, No. 165, pp. 413-418: The XIth Olympic Congress - The Program. (PDF; 108 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 25, 2010 (English).

- ↑ Barbara L. Drinkwater: Women in Sport: Volume VIII of the Encyclopedia of Sports Medicine . Blackwell Science Ltd, Oxford 1999, ISBN 0-632-05084-5 , pp. 661 (English) .

- ^ Arnd Krüger: The Unfinished Symphony. A History of the Olympic Games from Coubertin to Samaranch, in: James Riordan & Arnd Krüger (Eds.): The International Politics of Sport in the 20th Century. London: Spon 1999, 3-27.

- ^ Norbert Müller in Olympic Review, 1994, No.321, pp. 333-337: Twelve congresses for a century of Olympism. (PDF; 664 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 27, 2010 (English).

- ↑ Olympic Review, 1994, No. 321, p. 327: Themes. (PDF; 143 kB) LA84 Foundation (formerly Amateur Athletic Foundation of Los Angeles), 2007, accessed on September 27, 2010 (English).

- ^ A b c International Olympic Committee: XIII Olympic Congress - Proceedings. (PDF; 23.8 MB) The Olympic Movement, 2010, accessed on September 22, 2010 (English).

- ↑ International Olympic Committee: IOC Members. (PDF; 69 kB) The Olympic Movement, 2010, accessed on September 22, 2010 (English).

- ↑ International Olympic Committee: 2009 Olympic Congress Regulations. (PDF; 94 kB) The Olympic Movement, 2008, accessed on September 22, 2010 (English).