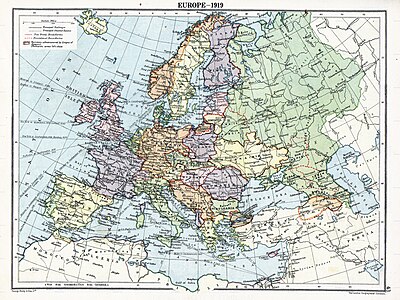

Aftermath of World War I

The fighting in World War I ended when an armistice took effect at 11:00 hours on November 11, 1918. In the aftermath of World War I the political, cultural, and social order of the world was drastically changed in many places, even outside the areas directly involved in the war. New countries were formed, old ones were abolished, international organizations were established, and many new and old ideas took a firm hold in people's minds.

Blockade of Germany

Throughout armistice the Allies maintained the naval blockade of Germany begun during the war. As Germany was dependent on imports, it is estimated that 750,000 [1] civilians had lost their lives during the war, and more died from starvation afterwards.

The continuation of the blockade after the fighting ended, as Robert Leckie wrote in Delivered From Evil, did "torment the Germans… driving them with the fury of despair into the arms of the devil". Terms of the Armistice did allow food to be shipped into Germany, but Allies required that Germany provide the ships. The German government was required to use its gold reserves, being unable to secure a loan from the United States. [2]. Some historians have argued that the slow food shipments in early 1919 was one of the primary causes of World War II; others have advocated the Allies should have been even harder on Germany.

The blockade was not lifted until late June of 1919 when the Treaty of Versailles was signed by most of the combatant nations.

Treaty of Versailles

After the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the signing of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28 1919 officially ended the war. Included in the 450 articles of the treaty were the demands that Germany officially accept responsibility for starting the war and pay heavy economic reparations. Germany itself was not included in the negotiations of the treaty and was forced to sign it (the alternative was continuing the war which would have probably led to a total occupation of Germany), which caused humiliation in the German people as the blame was shifted on them. The treaty was only concerning Germany, other treaties were made for different countries soon after. The treaty also included a clause to create the League of Nations. The US Senate never ratified this treaty and the US did not join the League, despite President Wilson's active campaigning in support of the League. The United States negotiated a separate peace with Germany, finalized in August 1921.

Influenza pandemic

A separate but related event was the great influenza pandemic. A virulent new strain of the flu first observed in the United States but misleadingly known as "Spanish Flu", was accidentally carried to Europe by infected American forces personnel. One in every four Americans had contracted the influenza virus. The disease spread rapidly through both the continental U.S. and Europe, eventually reaching around the globe, partially because many were weakened and exhausted by the famines of the World War. The exact number of deaths is unknown but about 50 million people are estimated to have died from the influenza worldwide,[1] [2] several times the victims of the World War. In 2005, a study found that, "The 1918 virus strain developed in birds and was similar to the 'bird flu' that today has spurred fears of another worldwide epidemic". [3]

Geopolitical and economic consequences

Revolutions

Perhaps the single most important event precipitated by the privations of World War I was the Russian Revolution of 1917. A socialist and often explicitly Communist revolutionary wave occurred in many other European countries from 1917 onwards, notably in Germany and Hungary.

As a result of the Mensheviks' failure to cede territory, German and Austrian forces defeated the Russian armies, and the new communist government signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918. In that treaty, Russia renounced all claims to Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland (specifically, the formerly Russian-controlled Congress Poland of 1815) and Ukraine, and it was left to Germany and Austria-Hungary "to determine the future status of these territories in agreement with their population." Later on, Lenin's government renounced also the Partition of Poland treaty, making it possible for Poland to claim its 1772 borders. However, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was rendered obsolete when Germany was defeated later in 1918, leaving the status of much of eastern Europe in an uncertain position.

Germany

- See: German Revolution

On the 28th of June, 1919, Germany was summoned to sign the Treaty of Versailles. Seeing as Germany accepted the blame for starting the war, they had to pay £6.6 billion in reparations. Germany had also had to reduce its army to 100 000 men, without tanks and was not allowed an air force. Germany lost land to France, Denmark, Czechoslovakia and Poland. There was a socialist revolution which lead to the brief establishment of a communist Germany, the resignation of the Kaiser and the birth of the Republic

Russian Empire

Russia, already suffering socially and economically, was torn by a deadly civil war that killed more than 55 million people in one way or another and devastated large areas of the country. During the Russian Revolution and subsequent civil war, many non-Russian nations gained brief or longer lasting periods of independence. Finland, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia gained relatively permanent independence, although the Baltic states were annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939.

Romania was initially formed from the union of Wallachia and Moldova and later gained Bessarabia from Russia. Additionally, the countries of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan were established in the Caucasus region. However, in 1922 these countries were invaded by the Soviets and proclaimed Soviet Republics. Similar events happened in Central Asia. After World War I, the Soviet Union was fortunate that Germany had lost the war as it was able to reject the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Had the Soviets not been able to do so, huge portions of rich territory and population would have been lost to them.

Austro-Hungarian Empire

With the war having turned decisively against the Central Powers, the peoples of the new Austro-Hungarian Empire lost faith in their allied countries, and even before the armistice in November, radical nationalism had already led to several declarations of independence in September and October 1918. Originally the Allies had hoped to maintain Austria-Hungary (although reduced) as a counterbalance to German power in central Europe and had interpreted the Woodrow Wilson's 14 points within the framework of a federal Austria-Hungary. However, due to progress of the war and lobbying by separatists from within and outside the Empire the Allied powers slowly began to recognise its nations as distinct entities.

The resolution of borders and governments in south-central Europe in the time after November 1918 was not easy. As the central government had ceased to operate in vast areas, these regions found themselves without a government and many new groups attempted to fill the void. During this same period, the population was facing food shortages and was, for the most part, demoralized by the losses incurred during the war. Various political parties, ranging from ardent nationalists, to social-democrats, to communists attempted to set up governments in the names of the different nationalities. In other areas, existing nation states such as Romania engaged regions that they considered to be theirs. These moves created de-facto governments that complicated life for diplomats, idealists, and the western allies.

The western allies were officially supposed to occupy the old Empire, but rarely had enough troops to do so effectively. They had to deal with local authorities who had their own agenda to fulfill. At the peace conference in Paris the diplomats had to reconcile these authorities with the competing demands of the nationalists who had turned to them for help during the war, the strategic or political desires of the Western allies themselves, and other agendas such as a desire to implement the spirit of the 14 points.

For example, in order to live up to the ideal of self determination laid out in the 14 points, Germans, whether Austrian or German, should be able to decide their own future and government. However, the French especially were concerned that an expanded Germany would be a huge security risk. Further complicating the situation, delegations such as the Czechs and Slovenians made strong claims on some German-speaking territories.

The result was treaties that compromised many ideals, offended many allies, and set up an entirely new order in the area. Many people hoped that the new nation states would allow for a new era of prosperity and peace in the region, free from the bitter quarrelling between nationalities that had marked the preceding fifty years. This hope proved far too optimistic. Changes in territorial configuration after World War I included:

- Establishment of the new republics of Austria and Hungary, disavowing any continuity with the empire and exiling the Habsburg family in perpetuity.

- Borders of newly independent Hungary did not include two-thirds of the lands of the former Kingdom of Hungary, though it did include most of the areas where the ethnic Magyars were in a majority. The new republic of Austria maintained control over most of the mostly German-dominated areas, but lost various other lands.

- Bohemia, Moravia, Opava Silesia and the western part of Duchy of Cieszyn, Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia formed the new Czechoslovakia.

- Galicia, eastern part of Duchy of Cieszyn, northern County of Orava and northern Spisz was transferred to Poland.

- The South Tyrol and Trieste were granted to Italy.

- Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Slovenia, and Vojvodina were joined with Serbia to form the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later Yugoslavia.

- Transylvania and Bukovina became parts of Romania.

These changes were recognized in, but not caused by, the Treaty of Versailles. They were subsequently further elaborated in the Treaty of Saint-Germain and the Treaty of Trianon.

The new states of eastern Europe nearly all had large national minorities. Millions of Germans found themselves in the newly created countries as minorities. One third of ethnic Hungarians found themselves living outside of Hungary. Many of these national minorities found themselves in bad situations because the modern governments were intent on defining the national character of the countries, often at the expense of the other nationalities.

The interwar years were hard for the Jews of the region. Most nationalists distrusted them because they were not fully integrated into 'national communities.' In contrast to times under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, Jews were often ostracized and discriminated against. Although anti-semitism had been widespread during Habsburg rule, Jews faced no official discrimination because they were, for the most part, ardent supporters of the multi-national state and the monarchy. Jews had feared the rise of ardent nationalism and nation states, because they foresaw the difficulties that would arise.

The economic disruption of the war and the end of the Austro-Hungarian customs union created great hardship in many areas. Although many states were set up as democracies after the war, one by one, with the exception of Czechoslovakia, they reverted to some form of authoritarian rule. Many quarreled amongst themselves but were too weak to compete effectively. Later, when Germany rearmed, the nation states of south- central Europe were unable to resist its attacks, and fell under German domination to a much greater extent than had ever existed in Austria-Hungary.

Ottoman Empire

At the end of the war the Ottoman government collapsed completely and the Ottoman Empire was divided amongst the victorious Entente powers with the signing of the Treaty of Sèvres on August 10, 1920. The fall of the empire led to the creation of the modern Middle East. The League of Nations granted France mandates over Syria and Lebanon and granted the United Kingdom mandates over Iraq and Palestine (which comprised two autonomous regions: Palestine and Transjordan). Parts of the Ottoman Empire on the Arabian Peninsula became part of what is today Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Italy and Greece were also given parts of Anatolia. At the suggestion of Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic Republic of Armenia was to be expanded into present-day eastern Turkey as reparation for the Armenian Genocide.[3] An autonomous area for the Kurds was also promised.

However, Turkish revolutionaries led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk rejected the terms regarding the patitioning of Anatolia at Sèvres and forced out the Greeks and Armenians while the Italians failed to establish themselves. The revolutionaries also suppressed Kurdish attempts to become independent in the 1920s. After Turkish resistance gained control over Anatolia, the Sèvres treaty was superseded by the Treaty of Lausanne which formally ended all hostilities and led to the creation of the modern Turkish republic. The new Lausanne treaty formally acknowledged the new League of Nations mandates in the Middle East, the cession of their territories on the Arabian Peninsula, and British sovereignty over Cyprus. It also cemented Turkey's new northeastern frontier with the Soviet Union which was determined in the Treaty of Kars. The Kars treaty established that the Bolsheviks would cede the former Armenian and Georgian provinces of Kars, Iğdır, Ardahan, and Artvin to Turkey in exchange for Adjara. The treaty was ratified in Yerevan on September 11, 1922 after the remainder of Armenia became part of the Soviet Union.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, funding the war had a severe economic cost. From being the world's largest overseas investor, it became one of its biggest debtors with interest payments forming around 40% of all government spending. Inflation more than doubled between 1914 and its peak in 1920, while the value of the Pound Sterling (consumer expenditure [4]) fell by 61.2%. Reparations in the form of free German coal depressed the local industry, precipitating the 1926 General Strike.

British private investments abroad were sold, raising £550 million. However £250 million new investment also took place during the war. The net financial loss was therefore approximately £300 million; less than two years investment compared to the pre-war average rate and more than replaced by 1928.[4] Material loss was "slight": the most significant being the sinking by German U-boats of 40% of British merchant fleet. Most of this was replaced in 1918 and all immediately after the war.[5] The military historian Correlli Barnett has argued that "in objective truth the Great War in no way inflicted crippling economic damage on Britain" but that the war "crippled the British psychologically but in no other way".[6]

Less concrete changes include the growing assertiveness of Commonwealth nations. Battles such as Gallipoli for Australia and New Zealand, and Vimy Ridge for Canada led to increased national pride and a greater reluctance to remain subordinate to Britain, leading to the growth of diplomatic autonomy in the 1920s. These battles were often decorated in propaganda in these nations as symbolic of their power during the war. Traditionally loyal dominions such as Newfoundland were deeply disillusioned by Britain's apparent disregard for their soldiers, eventually leading to the unification of Newfoundland into the Confederation of Canada. Colonies such as India and Nigeria also became increasingly assertive because of their participation in the war. The populations in these countries became increasingly aware of their own power and Britain's fragility.

In Ireland the delay in finding a resolution to the home rule issue, partly caused by the war, as well as the 1916 Easter Rising and a failed attempt to introduce conscription in Ireland, increased support for separatist radicals, and led indirectly to the outbreak of the Anglo-Irish War in 1919.

United States

In the USA, disillusioned by the failure of the war to achieve the high ideals promised by President Woodrow Wilson, the American people chose isolationism and, after an initial recession enjoyed several years of unbalanced prosperity until the 1929 Stock Market crash. However, American commercial interests did finance Germany's rebuilding and reparations efforts, at least until the onset of the Great Depression. The close relationships between American and German businesses became an embarrassment following the Nazi rise to power in Germany in the early 1930s.

France

France annexed the Independent Republic of Alsace-Lorraine, the country which had been established in the wake of Kaiser Wilhelm II's abdication, corresponding to the region which had been ceded to Prussia during the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. At the 1919 Peace Conference, president Clemenceau's aim was to insure that Germany would not seek revenge in the following years. To this purpose, the Chief commander of the Allied forces, Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, had demanded that for the future protection of France the Rhine river should now form the border between France and Germany. Based on history, he was convinced that Germany would again become a threat, and, on hearing the terms of the Treaty of Versailles that had left Germany substantially intact, he observed with great accuracy that "This is not Peace. It is an Armistice for twenty years."

The destruction brought upon the French territory was to be indemnified by the reparations negotiated at Versailles. This financial imperative dominated France's foreign policy through-out the twenties, leading to the 1923 Occupation of the Ruhr in order to force Germany to pay. However, Germany was unable to pay, and obtained support from the United States. Thus, the Dawes Plan was negotiated after President Raymond Poincaré's occupation of the Ruhr, and then the Young Plan in 1929.

Also extremely important in the War was the participation of French colonial troops, including the Senegalese tirailleurs, from Indochina, North Africa, and Madagascar. When these soldiers returned to their homelands and continued to be treated as second class citizens, many became the nucleus of pro-independence groups.

Furthermore, under the state of war declared during the hostilities, the French economy had been somewhat centralized in order to be able to shift into a "war economy," leading to a first breach with classical liberalism.

Finally, the socialist's support of the National Union government (including Alexandre Millerand's nomination as Minister of War) marked a shift towards the SFIO's turn towards social-democracy and participation in "bourgeois governments," although Léon Blum maintained a socialist rhetorics.

Italy

After the war, Italy failed to annex Dalmatia (which had been promised by Britain and France in the Treaty of London to induce Italy to join the war), and had to fight some more years to annex the city of Fiume, which had an Italian population, and this led several Italian politicians to speak of a "mutilated victory".

Indeed, it should not have been difficult to see how, among the Allied Powers, Italy had been the one which benefited the most from the outcome of the war. Whereas Britain and France still faced a Germany which had kept about 80 percent of her industrial and economic potential and thus could attempt a revanche in a matter of years, Italy had definitively gotten rid of her century-old enemy: instead of the Austro-Hungarian Empire there were now a number of smaller states, none of which could pose a credible threat, and some of them could even fall within the Italian sphere of influence.

With the annexation of Trento, Triest, South Tyrol, Friuli, Istria, Zara and some Dalmatian islands, Italy had completed her territorial expansion and could now rely on secure borders. Furthermore, Italian sovereignty over Rhodes and the Dodecanese had been officially recognized, as well as the Italian special interests in Albania. However, a Yugoslavian state was created in order to limit Italian influence and expansion on the Balkans, and thus Italy was quite isolated. The Italian politicians failed to perceive the positive elements of the peace treaties and stressed the negative ones, and so the myth of the "mutilated victory" spread, fueling the Fascist propaganda and helping Mussolini seize power.

During the war, Italy had suffered fewer casualties than Britain and much fewer than France, and the social problems she was facing afterward (an inflated war industry to reconvert to civilian production, the large number of crippled people no longer able to sustain themselves, the new role of women) were common to other Allied countries which, however, did not suffer an authoritarian drift. The difference between Italy and the other western allies lies in the more arbitrated economic and social conditions, which made it more difficult for Italy to recover from similar difficulties. Due to similar reasons, most south and east European countries had to face political unrest, dictatorship and fascism in the period between the World Wars.

China

The Republic of China who hoped to retake the Jiaozhou Bay occupied by Germany between 1898 and 1914 suffered diplomatic failure at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. The Chinese delegation also called for an end to Western imperialistic institutions in China, which was refused. Despite sending thousands of labourers to France during the war, China as an allied and victorious nation was refused the demand for the return of Jiaozhou Bay and the city was instead transferred to Japanese rule. This led to the May Fourth Movement, a profound social and political movement often cited as the birth of Chinese nationalism, which both the Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party consider an important period in their history. Subsequently, China did not sign the treaty, signing a separate peace treaty with Germany in 1921.

Territorial gains and losses

Nations that gained territory after World War I

- Yugoslavia (as the successor state of Kingdom of Serbia)

- Romania

- Greece

- France

- Italy

- Denmark

- Belgium

Nations that lost territory after World War I

- Bolshevist Russia (as the successor state of Russian Empire)

- Weimar Germany (as the successor state of German Empire)

- Austria (as the successor state of Cisleithania and the Austro-Hungarian Empire)

- Hungary (as the successor state of Transleithania and the Austro-Hungarian Empire)

- Turkey (as the successor state of Ottoman Empire)

- Bulgaria

Social trauma

The experiences of the war led to a sort of collective national trauma afterwards for all the participating countries. The optimism of 1900 was entirely gone and those who fought in the war became what is known as "the Lost Generation" because they never fully recovered from their experiences. One gruesome reminder of the sacrifices of the generation was the fact that this was one of the first times in warfare whereby more men had died in battles than to disease, which had been the main cause of deaths in most previous wars. The Russo-Japanese War was the first. For the next few years, much of Europe mourned privately and publicly; mourning and memorials were erected in thousands of villages and towns.

This social trauma manifested itself in many different ways. Some people were revolted by nationalism and what it had caused; so, they began to work toward a more internationalist world through organizations such as the League of Nations. Pacifism became increasingly popular. Others had the opposite reaction, feeling that only military strength could be relied on for protection in a chaotic and inhumane world that did not respect hypothetical notions of civilization. Certainly a sense of disillusionment and cynicism became pronounced. Nihilism grew in popularity. Many people believed that the war heralded the end of the world as they had known it, including the collapse of capitalism and imperialism. Communist and socialist movements around the world drew strength from this theory, enjoying a level of popularity they had never known before. These feelings were most pronounced in areas directly or particularly harshly affected by the war, such as central Europe, Russia and France.

Artists such as Otto Dix, George Grosz, Ernst Barlach, and Käthe Kollwitz represented their experiences, or those of their society, in blunt paintings and sculpture. Similarly, authors such as Erich Maria Remarque wrote grim novels detailing their experiences. These works had a strong impact on society, causing a great deal of controversy and highlighting conflicting interpretations of the war. In Germany, nationalists including the Nazis believed that much of this work was degenerate and undermined the cohesion of society as well as dishonouring the dead.

Remains of ammunition

Throughout the areas where trenches and fighting lines were located, such as the Champagne region of France, quantities of unexploded shells and other ammunition have remained, some of which remains dangerous and continues to cause injuries and occasional fatalities into the 21st century. Some are still found nowadays, for instance by farmers ploughing their fields and are called the iron harvest. Some of this ammunition contains chemical toxic products such as mustard gas. Cleanup of major battlefields is a continuing task with no end in sight for decades more. Squads remove, defuse or destroy hundreds of tons of unexploded ammunition every year in Belgium and France.

War memorials

Many towns in the participating countries have war memorials dedicated to local residents who lost their lives. Examples include:

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Australia

- Liberty Memorial, Kansas City, Missouri, United States

- Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont-Hamel

- The Cenotaph, London, United Kingdom

- Menin Gate Memorial, Ypres, Belgium

- Thiepval Memorial

- Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing at Passchendaele

- Verdun Memorial Museum

- Vimy Ridge Memorial, Vimy, France

- Gallipoli Memorial, Turkey

- Shrine of Remembrance, Melbourne, Australia

- Island of Ireland Peace Park, Messines, Belgium

- National War Memorial (Canada), Ottawa, Canada

- National War Memorial (Newfoundland), St. John's, Newfoundland, Canada

Tombs of the Unknown Soldier

- Monument to the Unknown Hero, Belgrade, Serbia

- Amar Jawan Jyoti, New Delhi, India

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Ottawa, Canada

- Arc de Triomphe, Paris, France

- The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior is in Westminster Abbey, London, UK

- Tomb of the Unknowns, Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, USA

- Tomba del milite ignoto, Rome, Italy

- Australian War Memorial, Canberra, Australia

- New Zealand Tomb of the Unknown Warrior, Wellington, New Zealand

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Syntagma Square, Athens, Greece

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, Bucharest, Romania

Notes

- ^ NAP

- ^ Influenza Report

- ^ President Wilson sends a special message to Congress

- ^ A. J. P. Taylor, English History, 1914 - 1945 (Oxford University Press, 1976), p. 123.

- ^ Ibid, p. 122.

- ^ Correlli Barnett, The Collapse of British Power (Pan, 2002), p. 424 and p. 426.

Resources

- Peacemakers: The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 and Its Attempt to End War by Margaret MacMillan, John Murray ISBN 0-7195-5939-1

- Peacemaking, 1919 by Harold Nicolson ISBN 1-931541-54-X

- Hew Strachan ed.: "The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War" is a collection of chapters from various scholars that survey the War.

- The Wreck of Reparations, being the political background of the Lausanne Agreement, 1932 by Sir John Wheeler-Bennett New York, H. Fertig, 1972.

The first major television documentary on the history of the war was the BBC's The Great War (1964), made in association with CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and The Imperial War Museum. The series consists of 26 forty-minute episodes featuring extensive use of archive footage gathered from around the world and eyewitness interviews. Although some of the programme's conclusions have been disputed by historians it still makes compelling and often moving viewing.

See also

Main articles

External links

- FirstWorldWar.com "A multimedia history of World War One"