Huldrych Zwingli: Difference between revisions

m →Politics, confessions, and the Second Kappel War (1529-1531): doubled word |

m →Legacy: drop 'that' from 'find that'; "find/to be" or "find that/is" |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

Zwingli was a humanist and a scholar with many devoted friends and disciples. He was a man who could communicate as easily with a ruler like Philip as well as to the ordinary man in front of his pulpit. He was more conscious of social obligations than Luther and he believed that the masses would accept a government guided by God’s word.<ref>{{Harvnb|Potter|1976|pp=417-418}}</ref> In December 1531, the council selected [[Heinrich Bullinger]] as his successor. He immediately removed any doubts about Zwingli’s orthodoxy and defended him as a prophet of Switzerland and a martyr.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gäbler|1986|pp=157-158}}</ref> |

Zwingli was a humanist and a scholar with many devoted friends and disciples. He was a man who could communicate as easily with a ruler like Philip as well as to the ordinary man in front of his pulpit. He was more conscious of social obligations than Luther and he believed that the masses would accept a government guided by God’s word.<ref>{{Harvnb|Potter|1976|pp=417-418}}</ref> In December 1531, the council selected [[Heinrich Bullinger]] as his successor. He immediately removed any doubts about Zwingli’s orthodoxy and defended him as a prophet of Switzerland and a martyr.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gäbler|1986|pp=157-158}}</ref> |

||

Scholars find |

Scholars find assessing Zwingli’s historical impact to be a difficult task. There are several problems: there is no agreement of what really constitutes "Zwinglianism"; even if Zwinglianism could be defined, it most certainly evolved under Heinrich Bullinger’s rule; and there is a serious lack of research of Zwingli’s influence on Bullinger and [[John Calvin]].<ref>{{Harvnb|Gäbler|1986|pp=155-156}}</ref> |

||

Bullinger adopted most of Zwingli’s points of doctrine. Like Zwingli, he summarised his theology several times, the most well-known being the [[Second Helvetic Confession]] of 1566. The confessional divisions of the Confederation stabilised under Bullinger. Meanwhile, Calvin had established the Reformation in [[Geneva]]. Calvin differed with Zwingli on the Eucharist and criticised him for regarding it as simply a metaphorical event. In 1549, however, Bullinger and Calvin succeeded in overcoming the differences in doctrine and produced the ''Consensus Tigurinus'' (Zürich Consensus). They declared that the Eucharist was not just symbolic of the meal, but they also rejected the Lutheran position that the blood and body of Christ is in [[Sacramental union|union with the elements]]. With this rapprochement, Calvin established his role in the [[Swiss Reformed Church|Swiss Reformed Churches]] and eventually in the wider world.<ref>{{Harvnb|Furcha|1985|pp=179-195}}, J. C. McLelland, |

Bullinger adopted most of Zwingli’s points of doctrine. Like Zwingli, he summarised his theology several times, the most well-known being the [[Second Helvetic Confession]] of 1566. The confessional divisions of the Confederation stabilised under Bullinger. Meanwhile, Calvin had established the Reformation in [[Geneva]]. Calvin differed with Zwingli on the Eucharist and criticised him for regarding it as simply a metaphorical event. In 1549, however, Bullinger and Calvin succeeded in overcoming the differences in doctrine and produced the ''Consensus Tigurinus'' (Zürich Consensus). They declared that the Eucharist was not just symbolic of the meal, but they also rejected the Lutheran position that the blood and body of Christ is in [[Sacramental union|union with the elements]]. With this rapprochement, Calvin established his role in the [[Swiss Reformed Church|Swiss Reformed Churches]] and eventually in the wider world.<ref>{{Harvnb|Furcha|1985|pp=179-195}}, J. C. McLelland, |

||

Revision as of 23:30, 6 February 2008

Ulrich (or Huldrych[1][2]) Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. He attended the University of Vienna and the University of Basel where he received the Master’s degree. He continued his studies while he served as pastor in Glarus and later in Einsiedeln. He studied and was influenced by the writings of Erasmus, a humanist scholar and theologian.

In 1519 he became the pastor of the Grossmünster in Zürich. He began to preach ideas on reforming the church in 1520. His first public controversy occurred in 1522 when he attacked the custom of fasting during Lent. He began publishing his ideas noting the corruption of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and promoting clerical marriage. The Zürich council supported Zwingli by calling for public disputations to resolve the issues. As the Reformation in Zürich progressed, Zwingli introduced a new communion liturgy to replace the mass. With the support of the Zürich council, monasteries were secularised. Zwingli also clashed with the radical wing of the Reformation, the Anabaptists, which resulted in their persecution.

Zwingli’s ideas spread to other parts of the Swiss Confederation, but they were resisted in several cantons that preferred to remain Catholic. Zwingli formed an alliance of Reformed cantons and the Confederation was divided along religious lines. In 1529 war between the two sides was averted at the last moment, but the tensions still remained. At the same time, Zwingli’s ideas also came to the attention of Martin Luther and other reformers. The various reformers tried to settle their differences at the Marburg Colloquy. Although they agreed on many points of doctrine, they differed on the doctrine of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

In 1531 religious tensions arose again when Zwingli’s alliance tried to apply pressure on the Catholic cantons. They responded with an attack at a moment when Zürich was badly prepared. Zwingli was killed in battle at the age of 47. Although his name is practically forgotten, Zwingli's legacy lives on in the basic confessions of the Reformed churches of today. He can rightfully be called, after Martin Luther and John Calvin, the "Third Man of the Reformation".

Biography

Early years (1484-1518)

Huldrych Zwingli was born 1 January 1484 in Wildhaus in what is now the canton of St. Gallen to a family of farmers, the third child among nine siblings. His father, Ulrich, played a leading role in the administration of the community. His primary schooling was provided by his uncle, Bartholomew, a cleric in Weesen. At ten years old, Zwingli was sent to Basel to obtain his secondary education where he learned Latin under Magistrate Gregory Bünzli. After three years in Basel, he stayed a short time in Bern with the humanist, Henry Wölfflin. The Dominicans in Bern tried to persuade Zwingli to join their order and it is possible that he was received as a novice. However, his father and uncle disapproved of such a course and he left Bern without completing his Latin studies. He enrolled in the University of Vienna in the winter semester of 1498 and according to the university records, he was expelled. He reenrolled in the summer semester of 1500. It is not known what happened in 1499 and it is not certain that he was truly expelled. Zwingli continued his studies in Vienna until 1502, at which time he transferred to the University of Basel where he received the Master of Arts degree (Magister) in 1506.[3][4]

Zwingli, like many of his contemporaries, went to work for the church having studied little theology. He celebrated his first mass in his hometown, Wildhaus, on 29 September 1506. His first ecclesiastical post was the pastorate of Glarus. He stayed there for ten years. It was in Glarus, whose soldiers were used as mercenaries in Europe, that Zwingli became acquainted with politics. The Swiss Confederation was involved in various campaigns with its neighbours, the French, the Habsburgs in Austria, and the Italian papal states. Zwingli placed himself solidly on the side of the Roman See. In return, Pope Julius II honoured Zwingli by providing him an annual pension. He took the role of chaplain in several campaigns in Italy including the Battle of Novara in 1513. However, the decisive defeat of the Swiss in the Battle of Marignano caused a shift in mood in Glarus in favour of the French rather than the pope. Zwingli found himself in a difficult position and he decided to move to Einsiedeln in the canton of Schwyz. By this time, he had become convinced that mercenary service was immoral and that Swiss unity was indispensable for any future achievements. Zwingli stayed in Einsiedeln for two years where he completely withdrew from politics in favour of ecclesiastical activities and personal studies.[5][6]

Zwingli's time as the pastor of Glarus and Einsiedeln was characterised as a time of inner growth and development. He perfected his Greek and took up the study of Hebrew. He read widely from classical, patristic, and scholastic sources. He exchanged scholarly letters among a circle of Swiss humanists. He studied the writings of Erasmus and he took the opportunity to meet him while Erasmus was in Basel between August 1514 and May 1516. Zwingli's turn to relative pacifism and the priority toward preaching can be traced to the influence of Erasmus.[7]

In late 1518, the post of the priest of the Grossmünster at Zürich became vacant. The canons of the foundation that administered the church recognised Zwingli's reputation as a fine preacher and writer. His opposition to the French and to mercenary service was quite acceptable to the Zürich politicians. His connection with humanists was also a decisive factor as several canons were sympathetic to Erasmian reform. Hence, on 11 December 1518, the canons elected Zwingli to become the stipendiary priest and on 27 December, he moved permanently to Zürich.[8][9]

Zürich ministry begins (1519-1521)

On 1 January 1519, Zwingli gave his first sermon in Zürich. Deviating from the prevalent practice of basing a sermon on the Gospel lesson of a particular Sunday, he began to exegete the Gospel of Matthew, reading through the book serially. He continued on subsequent Sundays with the Acts, the Epistles, and then the Old Testament. His motives for doing so is not clear, but it reveals his emphasis on exhortation in sermons to achieve moral improvement which would be in agreement with Erasmus. Sometime after 1520, Zwingli's theological model began to evolve into its own distinct form which was neither Erasmian nor Lutheran. Scholars do not agree on the process of how he developed his own model.[10]

Zwingli’s changing theological stance was gradually revealed through his sermons. One of the elderly canons who had supported Zwingli’s election, Konrad Hofmann, complained about his sermons in a letter. Zwingli attacked moral corruption and in the process he named individuals who were the targets of his denunciations. He accused monks of indolence and high living. He specifically rejected the veneration of saints and called for the need to distinguish between their true and fictional accounts. He casted doubts on hellfire and asserted that unbaptised children were not damned. He questioned the power of excommunication. He attacked the claim that tithing was a divine institution. Other canons supported Hofmann, but Zwingli insisted that he was not an innovator and that the sole basis of his teachings was Scripture.[11][12]

Within the diocese of Constance, a special indulgence for contributors to the building of St Peter’s in Rome was being offered by a Bernhardin Sanson. When he arrived at the gates of Zürich, Zwingli noted that the people were not properly informed about the conditions of the indulgence and were being induced to part with their money on false pretences. This was nearly two years after Martin Luther published his Ninety-five theses. The council of Zürich refused Sanson entry into the city. The authorities in Rome were anxious to contain the fire started by Luther. The Bishop of Constance denied any support of Sanson and he was recalled.[13]

In August 1519, Zürich was struck by an outbreak of the plague. At least one in four died. All those who could afford it left the city, but Zwingli remained and continued in his duties as a pastor. In September, he caught the disease and nearly died. He described his preparation for death in a poem, Zwingli's Pestlied, consisting of three parts, one describing the onset of the illness, one the closeness to death at its height, and the third the joy at recovery; the final verses of the first part read:[14]

|

|

In the years following his recovery, the opponents to Zwingli remained a minority. When a vacancy occurred among the canons of the church, Zwingli was elected to fulfill that vacancy on 29 April 1521. By becoming a canon, he became a full citizen of Zürich. He also retained his post as the pastor of the church.[15][16]

First rifts (1522-1524)

The first public controversy regarding Zwingli’s preaching broke out during the season of Lent in 1522. On the first fasting Sunday, 9 March, Zwingli and about a dozen other participants consciously transgressed the fasting rule by cutting and distributing two smoked sausages. Zwingli defended this act in a sermon which was published on 16 April, under the title Von Erkiesen und Freiheit der Speisen (Regarding the Choice and Freedom of Foods). He noted that no general valid rule on food can be derived from the Bible and that to transgress such a rule is not a sin and thus not punishable by the church. Even before the publication of this treatise, the diocese of Constance reacted by sending a delegation to Zürich. The city council condemned the violation of fasting, but assumed responsibility over ecclesiastical matters and requested the religious authorities for clarification on the issue. The bishop’s response on 24 May was to admonish the Grossmünster and city council and to repeat the traditional position.[17]

Following this event, Zwingli and other humanist friends petitioned the bishop on 2 July to abolish the requirement of celibacy on the clergy. The petition was reprinted for the public in German two weeks later as Eine freundliche Bitte und Ermahnung an die Eidgenossen (A Friendly Petition and Admonition to the Confederates). The issue was not just an abstract problem for Zwingli, as he had secretly married a widow, Anna Reinhard, earlier in the year. Their public wedding did not take place until 2 April 1524. They would eventually have four children: Regula, William, Huldrych, and Anna. As the petition was now addressed to the secular authorities, the bishop notified the Zürich government to maintain the ecclesiastical order. Other Swiss clergyman joined in Zwingli’s cause which encouraged him to make his first major statement of faith, Apolgeticeus Archeteles (The First and Last Word). He defended himself of charges of inciting unrest and heresy. He denied the ecclesiastical hierarchy any right to judge on matters of church order because of their corrupted state.[18]

Zürich disputations (1523)

The events of 1522 brought no clarification on the issues. Not only did the unrest between Zürich and the diocese continue, there were growing tensions with Zürich’s Confederation partners in the Swiss Diet. On 22 December, the Diet recommended that its members prohibit the new teachings, a strong indictment directed at Zürich. The city council felt obliged to take the initiative and to find its own solution. On 3 January 1523, it invited the clergy of the city and outlying region to a meeting to allow the factions to present their opinions. The bishop was invited to attend or to send a representative. The council would render a decision on who would be allowed to continue to proclaim their view. This meeting, the first Zürich disputation, took place on 29 January 1523.[19][20]

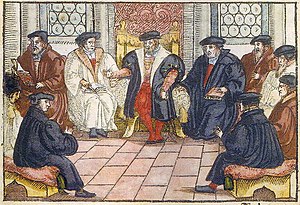

The meeting attracted a large crowd, approximately six hundred participants. The bishop sent a delegation led by his vicar general, Johannes Fabri. Zwingli summarised his position in the Schlussreden (Concluding Statements or the Sixty-seven Articles).[21] Fabri, who was ordered not to take part in the discussion and to function only as an observer, simply insisted on the necessity of the ecclesiastical authority. The decision of the council was that Zwingli would be allowed to continue his preaching and that all other preachers should teach only in accordance with Scripture.[22][23]

In September 1523, Leo Jud, Zwingli’s closest friend and colleague and pastor of St. Peterskirche, publically called for the removal of statues of saints and icons. This led to demonstrations and iconoclastic activities. The city council decided to work out the matter of church decorations in a second disputation. The essence of the mass and its sacrificial character was also included as a subject of discussion. An invitation was sent out for 26 October 1523. In addition to the Zürich clergy and the bishop of Constance, the invitation was extended to the lay people of Zürich, the dioceses of Chur and Basel, the University of Basel, and finally the twelve members of the Confederation. About nine hundred persons attended this meeting, but neither the bishop nor the Confederation sent representatives.

Zwingli again took the lead in the disputation and his opponent on the side of tradition was the canon, Konrad Hofmann. There was also a radical wing who demanded much faster action led by Conrad Grebel who would eventually found the Anabaptist movement. During the first three days, although the controversy of images and the mass were discussed, the arguments led to the question of whether the city council or the ecclesiastical government had the authority to decide on these issues. At this point, Konrad Schmid, a priest from Aargau and a follower of Zwingli, made a pragmatic suggestion. As images were not yet considered to be valueless by everyone, he suggested that pastors preach on this subject under threat of punishment. He believed the opinions of the people would gradually change and the voluntary removal of images would follow. Hence, Schmid rejected the radicals and their iconoclasm, but supported Zwingli’s position. In November the council passed ordinances in support of Schmid’s motion. Zwingli wrote a booklet on the evangelical duties of a minister, Kurze, christliche Einleitung (Short Christian Introduction), and the council sent it out to the clergy and the members of the Confederation.[24][25]

Reformation progresses in Zürich (1524-1525)

In December 1523, the council set a deadline of Pentecost in 1524 for a solution in eliminating the mass and images. Zwingli gave a formal opinion in Vorschlag wegen der Blider und der Messe (Proposal Concerning Images and the Mass). He did not urge an immediate, general abolition. The council decided on the orderly removal of images within Zürich, but rural congregations were granted the right to remove them based on majority vote. The decision on the Mass was postponed.[26]

Evidence of the effect of the Reformation was seen in early 1524. Candlemas was not celebrated, processions of robed clergy ceased, worshippers did not go with palms or relics on Palm Sunday to the Lindenhof, and triptychs remained covered and closed after Lent.[27] Opposition to the changes came from Konrad Hofmann and his followers, but the council decided in favour of keeping the government mandates. When Hofmann left the city and the opposition from pastors hostile to the Reformation broke down. The bishop of Constance also tried to intervene in defending the mass and the veneration of images. Zwingli wrote an official response for the council thereby severing all ties between the city and the diocese.[28]

Although the council had hesitated in abolishing the mass, the decrease in the exercise of traditional piety allowed pastors to be unofficially released from the requirement of celebrating mass. As individual pastors altered their practices as each saw fit, Zwingli was prompted to address this disorganised situation by designing a communion liturgy in the German language. This was published in Aktion oder Brauch des Nachtmahls (Act or Custom of the Supper). Shortly before Easter, Zwingli and his closest associates requested the council to cancel the mass and to introduce the new public order of worship. On Maundy Thursday, 13 April 1525, Zwingli celebrated communion under his new liturgy. In order to avoid outward display, wooden cups and plates were used. The congregation sat at set tables to emphasise the meal aspect. The sermon was the focal point of the service and there was no organ music or singing. The importance of the sermon in the worship service was underlined by Zwingli’s proposal to limit the celebration of communion to four times a year.[29]

For sometime Zwingli had accused mendicant orders of hypocrisy and demanded their abolition in order to support the truly poor. He suggested to change the monasteries into hospitals and welfare institutions and to incorporate their wealth into a welfare fund. This was done by reorganising the foundations of the Grossmünster and Fraumünster and pensioning off remaining nuns and monks in various monasteries. The council secularised the church properties and established new welfare programs for the poor. Zwingli requested to establish a Latin school, the Prophecy, at the Grossmünster. The council agreed and it was officially opened 19 June 1525 with Zwingli and Jud participating as teachers. It served to retrain and reeducate the clergy. The Zürich Bible translation, traditionally attributed to Zwingli, bears the mark of teamwork from the Prophecy school. Scholars have not yet attempted to clarify Zwingli's share of the work based on external and stylistic evidence.[30][31]

Conflict with the Anabaptists (1525-1527)

Shortly after the second Zürich disputation, many in the radical wing of the Reformation became convinced that Zwingli was making too many concessions to the Zürich council. Privately, Conrad Grebel, the leader of the radicals, spoke disparagingly of Zwingli. They rejected the role of civil government and demanded the immediate establishment of a congregation of the faithful. The emerging Anabaptist movement placed particular importance on the rejection of infant baptism. On 15 August 1524 the council insisted on the obligation to baptise all newborn infants. Zwingli secretly conferred with Grebel’s group and late in 1524, the council called for official discussions. When talks were broken off, Zwingli published Wer Unsache gebe zu Aufruhr (Whoever Causes Unrest) clarifying the opposing point-of-views. On 17 January 1525 a public debate was held and the council decided in favour of Zwingli. Anyone refusing to have their children baptised were required to leave Zürich. The radicals ignored these measures. On 21 January they performed the first adult baptisms and founded their own Anabaptist community in Zollikon.[32]

Zwingli attacked one of the best theologically educated Anabaptists, Balthasar Hubmaier, when he was temporarily staying in Zürich. This was published in Antwort über Balthasar Hubmaiers Taufbüchlein (Response to Balthasar Hubmaier’s Booklet on Baptism). In spite of his attack, the movement was not suppressed and the Zürich government took extreme measures, going so far as to execute Felix Manz, a colleague of Grebel, on 5 January 1527.[33][34]

Reformation in the Confederation (1526-1528)

On 8 April 1524, five cantons, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, and Zug, formed an alliance, die fünf Orte (the Five States) in order to defend themselves from Zwingli’s Reformation.[27] They contacted the opponents of Martin Luther including John Eck who had debated Luther in Leipzig in 1519. Eck offered to dispute Zwingli to which Zwingli accepted. However, they could not agree on the selection of the judging authority, the location of the debate, and the use of the Swiss Diet as a court. Because of the disagreements, Zwingli decided to boycott the disputation. On 19 May 1526, all the cantons sent delegates to Baden. Although Zürich’s representatives were present, they did not participate in the sessions. Eck led the Catholic party while the reformers were represented by Johannes Oecolampadius of Basel, a theologian from Württemberg who had carried an extensive and friendly correspondence with Zwingli. While the debate proceeded, Zwingli was kept informed of the proceedings and printed pamphlets giving his opinions. It was of little use as the Diet decided against Zwingli. He was to be banned and his writings were no longer to be distributed. Of the thirteen Confederation members, Glarus, Solothurn, Fribourg, and Appenzell as well as the Five States voted against Zwingli. Bern, Basel, Schaffhausen, and Zürich supported him.[35]

The Baden disputation exposed a deep rift in the Confederation on matters of religion. The Reformation was now emerging in other states. The city of St Gallen, an affiliated state to the Confederation, was led by a reformed mayor, Joachim Vadian, and the city abolished the mass in 1527, just two years after Zürich. In Basel, although Zwingli had a close relationship with Oecolampadius, the government did not officially sanction any reformatory changes until 1 April 1529 when the mass was prohibited. Schaffhausen, which had closely followed Zürich’s example, formally adopted the Reformation in September 1529. In the case of Bern, Berchtold Haller, the priest at St Vincent Münster, and Niklaus Manuel, the poet, painter, and politician, had campaigned for the reformed cause. But it was only after another disputation that Bern counted itself as a canton of the Reformation. Four hundred and fifty persons participated including pastors from Bern and other cantons as well as theologians from outside the Confederation such as Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Capito from Strasbourg, Ambrosius Blarer from Constance, and Andreas Althamer from Nürnberg. Eck and Fabri refused to attend and the Catholic cantons did not send representatives. The meeting started on 6 January 1528 and lasted nearly three weeks. Zwingli took the main share of the burden in defending the Reformation and he preached twice in the Münster. On 7 February 1528 the council decreed that the Reformation was established in Bern.[36]

First Kappel War (1529)

Even before the Bern disputation, Zwingli was canvassing for an alliance of reformed cities. Once Bern became officially reformed, a new alliance, das Christliche Burgrecht (the Christian Fortress Law) was formed. The first meetings were held in Bern between representatives of Bern, Constance, and Zürich on 5-6 January 1528. Other cities including Basel, Biel, Mülhausen, Schaffhausen, and St Gallen, eventually joined the alliance. The Five States felt isolated and so on 22 April 1529 they formed die Christliche Vereinigung (the Christian Alliance) with Ferdinand of Austria.[37][38]

Soon after the Austrian treaty was signed, a reformed preacher, Jacob Kaiser, was captured in Uznach and executed in Schwyz. This triggered a strong reaction from Zwingli, where he drafted Ratschlag über den Krieg (Advice About the War) for the government. It stated Zürich's justifications for an attack on the Catholic states and measures to be taken. Before Zürich could implement his plans, a delegation from Bern, including Niklaus Manuel, arrived. They asked that the matter be settled peacefully. Manuel noted the danger to Bern due to the presence of Valais and Savoy on its southern flank. He then said, "You cannot really bring faith by means of spears and halberds."[39] Zürich, however, decided that it would act alone knowing that Bern would be obliged to acquiesce. War was declared on 8 June 1529. Zürich was able to raise an army of 30000 men. The Five States were abandoned by Austria and could raise only 9000 men. The two forces met near Kappel, but war was prevented due to the intervention by Hans Aebli, a relative of Zwingli, who pleaded for an armistice.[40][41]

Zwingli was obliged to state the terms of the armistice. He demanded the dissolution of the Christian Alliance; unhindered preaching of the Bible in the Catholic states; prohibition of the pension system; payment of war reparations; and compensation to the children of Jacob Kaiser. Manuel was involved in the negotiations. Bern was not ready to insist on the unhindered preaching or the prohibition of the pension system. Zürich and Bern was not in agreement. The Five States only pledged to the dissolution of the Alliance. This was a bitter disappointment for Zwingli and it marked his decline in political influence.[42] The first Land Peace of Kappel, der erste Landfriede, ended the war on 24 June.[43]

Marburg Colloquy (1529)

While Zwingli carried on the political work of the Swiss Reformation, he also continued to work on theological developments with his colleagues. The disagreement between Luther and Zwingli on the intrepretation of the Eucharist originated when Andreas Karlstadt, Luther’s former colleague from Wittenberg, published three pamphlets on the Lord’s Supper in which Karlstadt rejected the idea of a real presence in the elements. These pamphlets, published in Basel in 1524, received the approval of Oecolampadius and Zwingli. Luther rejected Karlstadt’s arguments and considered Zwingli primarily to be a partisan of Karlstadt. Zwingli began to express his thoughts on the Eucharist in several publications including de Eucharistia (On the Eucharist). He attacked the idea of the real presence and presented his understanding that the word “is” in the words of the institution, “This is my body, this is my blood”, takes the meaning of “signifies”. Hence, the words are understood as a metaphor and Zwingli claimed that there was no real presence during the Eucharist. In effect, the meal was symbolic of the Last Supper.[44]

By spring 1527, Luther gave a strong reaction to Zwingli’s views in a treatise placing his disagreement with Zwingli in the context of a battle against Satanic forces. The controversy continued until 1528 when efforts began to build bridges between the Lutheran and the Zwinglian views. Martin Bucer tried to mediate while Philip of Hesse, who wanted to form a political coalition of all Protestant forces, invited the two parties to Marburg to discuss their differences. This event became known as the Marburg Colloquy.[45]

Zwingli accepted Philip's invitation fully believing that he would be able to convince Luther. By contrast, Luther did not expect anything to come out of the meeting and had to be urged by Philip to attend. Zwingli, accompanied by Oecolampadius, arrived on 28 September 1529. Luther and Philipp Melanchthon arrived shortly thereafter. Other theologians also participated. The debates were held from 1-3 October. The results were published in the fifteen Marburg Articles and the participants agreed on fourteen of the articles. The fifteenth article established the differences in their views on the presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Afterwards, each side was convinced that they were the victors, but in fact the controversy was not resolved and the final result was the formation of two different Protestant confessions.[46]

Politics, confessions, and the Second Kappel War (1529-1531)

With the failure of the Marburg Colloquy and the split of the Confederation, Zwingli set his goal on an alliance with Philip of Hesse. He kept a lively correspondence with Philip. Bern refused to participate, but after a long process, Zürich, Basel, and Strasbourg signed a mutual defense treaty with Philip in November 1530. Zwingli also personally negotiated with France's diplomatic representative, but the two sides were too far apart. France wanted to maintain good relations with the Five States. Approaches to Venice and Milan also failed.[47]

As Zwingli was working on establishing these political alliances, Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, invited Protestants to the Augsburg Diet to present their views so that he could make a verdict on the issue of faith. The Lutherans presented the Augsburg Confession. Under the leadership of Martin Bucer, the cities of Strasbourg, Constance, Memmingen, and Lindau produced the Tetrapolitan Confession. This document attempted to take a middle position between the Lutherans and Zwinglians. It was too late for the Fortress Law cities to produce a confession of their own. Zwingli then produced his own private confession, Fidei ratio (Account of Faith). Zwingli explained his faith in twelve articles conforming to the articles of the Apostles' Creed. The tone was strongly anti-Catholic as well as anti-Lutheran. The Lutherans did not react officially, but criticised it privately. Zwingli's and Luther's old opponent, John Eck, counterattacked with a publication, Refutation of the Articles Zwingli Submitted to the Emperor.[48]

When Philip of Hesse formed the Schmalkaldic League at the end of 1530, the four cities of the Tetrapolitan Confession joined on the basis of a Lutheran interpretation of that confession. Given the flexibility of the league's entrance requirements, Zürich, Basel, and Bern also considered joining. However, Zwingli could not reconcile the Tetrapolitan Confession with his own beliefs and wrote a harsh refusal to Bucer and Capito. This offended Philip to the point where relations with the League was severed. The Fortress Law cities now had no external allies to help deal with internal Confederation religious conflicts.[49]

The peace treaty of the First Kappel War did not define the right of unhindered preaching in the Catholic states. Zwingli interpreted this to mean that preaching should be permitted, but the Five States suppressed any attempts to reform. The Fortress Law cities considered different means of applying pressure to the Five States. Basel and Schaffhausen advocated diplomacy while Zürich wanted armed conflict. Bern took the middle position. Zwingli and Jud unequivocally advocated an attack on the Five States. Eventually Bern prevailed and in May 1531, Zürich reluctantly agreed to setup a food blockade. It failed to have any effect and in October Bern decided to withdraw the blockade. Zürich urged its continuation and the Fortress Law cities began to quarrel among themselves.[50]

On 9 October 1531, in a surprise move, the Five States declared war on Zürich. Zürich's mobilisation was slow due to the internal squabbling and on 11 October, three thousand five hundred badly deployed men encountered a Five States force nearly double in size near Kappel. Many pastors were among the soldiers including Zwingli. The battle lasted less than one hour and Zwingli was among the five hundred casualties in the Zürich army.[51] Zwingli considered himself first and foremost a soldier of Christ; second a defender of his country, the Confederation; and third a leader of his city, Zürich, where he lived the last twelve years. However, he died at the age of 47, ironically not for Christ nor for the Confederation, but for Zürich.[52]

Legacy

| Part of a series on |

| Reformed Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

Zwingli was a humanist and a scholar with many devoted friends and disciples. He was a man who could communicate as easily with a ruler like Philip as well as to the ordinary man in front of his pulpit. He was more conscious of social obligations than Luther and he believed that the masses would accept a government guided by God’s word.[53] In December 1531, the council selected Heinrich Bullinger as his successor. He immediately removed any doubts about Zwingli’s orthodoxy and defended him as a prophet of Switzerland and a martyr.[54]

Scholars find assessing Zwingli’s historical impact to be a difficult task. There are several problems: there is no agreement of what really constitutes "Zwinglianism"; even if Zwinglianism could be defined, it most certainly evolved under Heinrich Bullinger’s rule; and there is a serious lack of research of Zwingli’s influence on Bullinger and John Calvin.[55]

Bullinger adopted most of Zwingli’s points of doctrine. Like Zwingli, he summarised his theology several times, the most well-known being the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566. The confessional divisions of the Confederation stabilised under Bullinger. Meanwhile, Calvin had established the Reformation in Geneva. Calvin differed with Zwingli on the Eucharist and criticised him for regarding it as simply a metaphorical event. In 1549, however, Bullinger and Calvin succeeded in overcoming the differences in doctrine and produced the Consensus Tigurinus (Zürich Consensus). They declared that the Eucharist was not just symbolic of the meal, but they also rejected the Lutheran position that the blood and body of Christ is in union with the elements. With this rapprochement, Calvin established his role in the Swiss Reformed Churches and eventually in the wider world.[56][57]

Outside of Switzerland, there is no church that declares itself to be of Zwinglian origin. Scholars speculate as to why Zwinglianism was not more widely diffused.[58] Although his name is practically forgotten, Zwingli's legacy lives on in the basic confessions of the Reformed churches of today.[59] He can rightfully be called, after Luther and Calvin, the "Third Man of the Reformation".[60]

Theology

The study of the theology of Huldrych Zwingli has been recently stimulated by the publication of a modern critical edition of his works.[61] The Bible is central in Zwingli’s work as a reformer and is crucial in the development of his theology. He took scripture as the inspired word of God, which gave it authority over the writings of man such as patristic sources and the ecumenical councils. He did not accept the apocryphal books as canonical and he did not consider the Revelation of St John in high regard.[62]

Zwingli rejected the word "sacrament" in the popular usage of his time. For ordinary people, the word meant some kind of holy action of which there is inherent power to free the conscience from sin. For Zwingli, a sacrament was an initiatory ceremony or a pledging as in the case of baptism and the Lord’s Supper.[63] His writings on baptism arose out of his conflict with the Anabaptists. He defended the practice of infant baptism by accusing the Anabaptists that they added to the word of God and that there is no law forbidding infant baptism. He also challenged Catholics by denying that the water of baptism can be ascribed a power to wash away sin.[64] He developed the symbolic view of the Eucharist starting in 1524. He used scripture to argue against transubstantiation, the key text being John 6:63, "It is the Spirit who gives life, the flesh is of no avail". He used the same argument against Luther’s view. The Marburg Colloquy required Zwingli to express his views in a negative manner rather than being conciliatory. However, it helped to clarify the distinctions between the two reformers.[65]

Music

Zwingli enjoyed music greatly and could play, among other instruments, the violin, the harp, flute, dulcimer and hunting horn. He would sometimes amuse the little ones of his flock on his lute and was so keen on his instruments that his enemies took advantage of it, calling him “the evangelical lute-player and fifer.” Three of Zwingli's Lieder or hymns have been preserved: besides the Pestlied mentioned above the Kappeler Lied, by its incipit Herr nun heb den Wagen selb, according to Bullinger composed during the campaign of the first war of Kappel (1529), and an adaptation of Psalm 65 (ca. 1525).[66] These songs however were not meant to be sung during worship services. In the sixteenth century, they were published in certain hymnals, but they are not identified as hymns of the Reformation.[67]

Zwingli criticised the practice of priestly chanting and monastic choirs in the church. The criticism dates from 1523 when he attacked certain practices during a church service. He associated the music with images and vestments which he felt diverted people’s attention from true spiritual worship. It is not known what he thought about early Protestant musical practices as was found in Lutheran churches. He did not express an opinion on congregational singing and he made no effort to encourage it.[68] Scholars have demonstrated new findings regarding Zwingli and music in the church. Gottfried W. Locher writes, "The old assertion 'Zwingli was against church singing' holds good no longer.... Zwingli's polemic is concerned exclusively with the medieval Latin choral and priestly chanting and not with the hymns of evangelical congregations or choirs". He goes on to say that "Zwingli freely allowed vernacular psalm or choral singing. In addition, he even seems to have striven for lively, antiphonal, unison recitative". Locher then summaries his comments on Zwingli's view of church music as follows: "The chief thought in his conception of worship was always 'conscious attendance and understanding' — 'devotion', yet with the lively participation of all concerned".[69]

See also

Notes

- ^ Potter 1976, p. 1. According to Potter, "Huldrych" was his preferred spelling, although he did use "Ulrich" as well.

- ^ Ulrich was his given name, after Saint Ulrich of Augsburg. He began to use the similarly-sounding Huldrych "full of grace" at some point as a humanist word-game. After Zwingli's death, the alteration of Zwingli's first name became popular among protestant authors, in modernized spelling also as Huldreich, since they had no interest to perpetuate the veneration of a saint implied in the name.[citation needed] The etymology of the Germanic name Ulrich is "rich in heritage/estate".

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 23–24

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 1–12

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 29–33

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 22–40

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 33–41

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 43–44

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 45–46

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 44–49

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 49–52

- ^ Potter 1976, p. 66

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 44, 66–67

- ^ see e.g. Potter 1976, pp. 69–70

- ^ Gäbler 1986, p. 51

- ^ Potter 1976, p. 73

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 52–56

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 57–59

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 63–65

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 97–100

- ^ Potter 1976, p. 99

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 67–71

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 100–104

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 76–81

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 130–135

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 81–82

- ^ a b Potter 1976, p. 138

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 82–83

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 105–106

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 222–223

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 97–103

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 125–126

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 128–129

- ^ "The Reformation and the Anabaptists, Steps to Reconciliation". Retrieved 2008-01-29.. The descendant of the Zwinglian Reformation, the Reformed Church of Zürich, and the descendants of the Anabaptist movement (Amish, Hutterites, and Mennonites) held a Reconciliation Conference at the Grossmünster on 26 June 2004. See also "Mennonite World Conference Press Release". Retrieved 2008-01-29. and "Too Late for an Apology After 477 years?" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-01-29..

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 111–113

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 113–119

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 119–120

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 352–355

- ^ Potter 1976, p. 364. In German, "Warlich man mag mit spiess und halberten den glouben nit ingeben."

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 120–121

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 362–367

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 367–369

- ^ Potter 1976, p. 371

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 131–135

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 135–136

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 136–138

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 141–143

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 143–146

- ^ Gäbler 1986, p. 148

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 148–150

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 150–152

- ^ Potter 1976, p. 414

- ^ Potter 1976, pp. 417–418

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 157–158

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 155–156

- ^ Furcha 1985, pp. 179–195, J. C. McLelland, "Meta-Zwingli or Anti-Zwingli? Bullinger and Calvin in Eucharistic Concord"

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 158–159

- ^ Furcha 1985, pp. 1–12, Ulrich Gäbler, "Zwingli the Loser".

- ^ Gäbler 1986, p. 160

- ^ Rilliet 1964

- ^ e.g., Huldrych Zwingli, Schriften (4 vols.), eds. Th. Brunnschweiler and S. Lutz, Zürich (1995), ISBN 978-3290109783

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 51–58

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 180–185

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 194–204

- ^ Stephens 1986, pp. 218–250

- ^ Hannes Reimann, Huldrych Zwingli - der Musiker, Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 17 2./3. (1960), pp. 126-141

- ^ Gäbler 1986, p. 108

- ^ Gäbler 1986, pp. 107–108

- ^ Locher 1981

References

- Furcha, E. J., ed. (1985), Huldrych Zwingli, 1484-1531: A Legacy of Radical Reform: Papers from the 1984 International Zwingli Symposium McGill University, Montreal: Faculty of Religious Studies, McGill University, ISBN 0-7717-0124-1.

- Gäbler, Ulrich (1986), Huldrych Zwingli: His Life and Work, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, ISBN 0-8006-0761-9.

- Locher, Gottfried W. (1981), Zwingli's Thought : New Perspectives, Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Potter, G. R. (1976), Zwingli, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20939-0.

- Rilliet, Jean (1964), Zwingli: Third Man of the Reformation, London: Lutterworth Press, OCLC 820553.

- Stephens, W. P. (1986), The Theology of Huldrych Zwingli, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-19-826677-4.

External links

- Biography of Anna Reinhard in Leben magazine in PDF

- Website of the Zwingli Association and Zwingliana journal