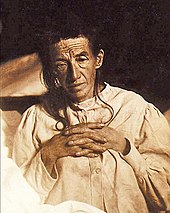

Alois Alzheimer

Alois Alzheimer (born June 14, 1864 in Marktbreit ; † December 19, 1915 in Breslau ) was a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist . He was the first to describe a dementia that is now called Alzheimer's disease .

Life

School time and studies

Alois Alzheimer was the eldest son from the second marriage of the notary Eduard Alzheimer and his wife Barbara Theresia born. Busch, a sister of the first wife Eva-Maria geb. Bush. He attended school in Marktbreit and the humanistic grammar school in Aschaffenburg .

Alzheimer's studied medicine at the University of Würzburg , interrupted by a stopover at the University of Tübingen . In 1884 he became active in the Corps Franconia Würzburg . His dissertation, completed in 1887 under Albert von Koelliker at the Anatomical Institute in Würzburg, deals histologically with the function of the wax glands . In 1888 he graduated with the grade "very good" and received his license to practice medicine.

Frankfurt

In 1888 Alzheimer successfully applied as an assistant doctor to the “Städtische Anstalt für Irre und Epileptische” founded by the psychiatrist Heinrich Hoffmann - also known as the author of the Struwwelpeter stories - in Frankfurt am Main . The head of the institution, Emil Sioli , his senior physician Franz Nissl and Alzheimer joined forces to introduce a new method of treatment for the mentally ill, which they called "non-restraint" and whose essential feature was the avoidance of straitjackets, force-feeding and other compulsive means. Instead, bed treatment of the sick was introduced in large guard rooms, and later treatment of particularly restless patients with warming long baths, the water temperature of which was monitored by the staff. Some patients were allowed to move freely in the clinic's park, others were even taken on excursions into the surrounding area.

In 1894 Wilhelm Erb asked him to come to Algeria and examine his patient Otto Geisenheimer, a Frankfurt diamond dealer. The patient suffered from brain softening and died of the disease. Alzheimer fell in love with the widow Cecilie Geisenheimer and returned with her to Frankfurt. Unaffected by Alzheimer's, the Jew converted to Catholicism and married Alzheimer's church in February 1895.

The daughter Gertrud was born in March 1895, followed by the children Hans (* 1896) and Maria (* 1900). The time was marked by family happiness and professional satisfaction. In 1901, however, Cecilie Alzheimer fell ill and died on February 28th. To cope with his grief, Alzheimer's threw himself into work. In November 1901 he met the patient whose description would later make him the namesake of Alzheimer's disease ( see below ).

Heidelberg and Munich

In 1902 Alzheimer became a scientific assistant to Emil Kraepelin at the Psychiatric University Clinic in Heidelberg . In 1903 Alzheimer followed his mentor Kraepelin to Munich . Here he completed his habilitation thesis Histological Studies on the Differential Diagnosis of Progressive Paralysis in the same year . Alzheimer was a private lecturer and senior physician in Munich. Research, scientific publications and lectures shaped this time.

In 1906 the dementia patient Auguste Deter, who had examined Alzheimer's in Frankfurt, died. He had the medical files and the brain sent to Munich and examined the brain. In November he gave a lecture on the noticeable changes in the patient's brain. The following year he published the article About a strange disease of the cerebral cortex in the Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie .

When Alois Alzheimer examined the brain of his deceased patient Johann F. in 1911, he found noticeable changes here too. These are now known as the “plaque-only” variant of dementia. Alzheimer's found similar tissue changes in the brain even in cases of senile dementia. He came to the conclusion that senile dementia was a later onset and more slowly progressing variant of the disease he described in 1906. This view has led to the inaccurate distinction between senile and presenile dementia.

Wroclaw

Alzheimer's last station in life was in Breslau . In 1912 he succeeded Karl Bonhoeffer as full professor at the Friedrich Wilhelm University and director of the "Royal Psychiatric and Mental Clinic". The advocacy of his teacher Kraepelin helped, because the favorite for this position had been Eugen Bleuler from Zurich.

In 1915 there was a rapid decline in his health. Heart problems, kidney failure and shortness of breath indicated a quick end. Alois Alzheimer died on December 19, 1915 with his family. Four days later he was buried next to his wife in the main cemetery in Frankfurt am Main .

At his clinic, Hans Gerhard Creutzfeldt also completed part of his neurological training at short notice and treated a young woman there in 1913, in whom he described spongiform encephalopathy for the first time , which he was only able to publish in 1920 and which then became Creutzfeldt after him and the neurologist Alfons Jakob -Jakob's disease.

The Auguste Deter case

Recording of behavioral problems (1901)

On November 25, 1901, Alzheimer's met the patient who was to make him famous in the Frankfurt sanatorium: Auguste Deter. Her husband took her to the asylum after she had changed a lot in a year. She had become jealous, could no longer do simple household chores, hidden objects, felt persecuted and intrusively bothered the neighborhood. Auguste D.'s medical record was found in the archive of the psychiatric clinic in Frankfurt am Main in 1996.

As always, Alzheimer's recorded the first data and findings. He asked:

- "What's your name?"

- "Auguste."

- "Family name?"

- "Auguste."

- "What's your husband's name?" - Auguste Deter hesitates, finally answers:

- "I think ... Auguste."

- "Her husband?"

- "I see."

- "How old are they?"

- "51."

- "Where do you live?"

- "Oh, you have already been with us."

- "Are you married?"

- "Oh, I'm so confused."

- "Where are you here?"

- "Here and everywhere, here and now, you mustn't blame me."

- "Where are you here?"

- "We will still live there."

- "Where's your bed?"

- "Where should it be?"

For lunch, Ms. Auguste D. has pork with cauliflower .

- "What are you eating?"

- "Spinach." (She chews the meat)

- "What are you eating now?"

- "I eat potatoes first and then horseradish ."

- "Write a five."

- She writes: "A woman"

- "Write an eight."

- She writes: "Auguste" (While writing she says repeatedly: "I've lost myself, so to speak".)

Over the next few weeks, further patient interrogation confirmed the severe mental confusion. The patient often moaned and said “oh God”. Alzheimer's found that the patient had no orientation about time or whereabouts, could hardly remember details from her life and often gave answers that were unrelated to the question and otherwise remained unrelated. Their moods quickly alternated between fear, suspicion, rejection and tearfulness. She could not be allowed to walk through the clinic on her own as she tended to hit all the other patients in the face and was beaten by them for doing so.

It wasn't the first time Alzheimer's had encountered a severely confused patient. However, he did not attach any importance to previous cases with similar findings because the patients were often nearly 70 years or older. Auguste Deter aroused his curiosity because she was only 51 years old when she was admitted. When questioned, she said several times: “I've lost myself, so to speak” - she was obviously aware of her helplessness. Alzheimer's gave the disease the name "Disease of Forgetting".

Later he inquired from Munich in Frankfurt about Deter's condition and prevented her being transferred to another clinic, which was planned for financial reasons, because he absolutely wanted to examine this patient again - after her death.

Examination of the brain (1906)

On April 9, 1906, Alzheimer received a call from Frankfurt in Munich: Auguste Deter had died. Alzheimer had the patient's medical file and brain sent to them. The file revealed that the state of mind had deteriorated massively in recent years. The cause of death was blood poisoning caused by pressure ulcers (bedsores) .

The microscopic examination of the brain revealed nerve cells that had perished in areas and protein deposits (so-called plaques ) throughout the cerebral cortex. On November 3, 1906, Alzheimer presented the clinical picture, which was later named after him, as an independent disease to psychiatrists and neurologists at a symposium in Tübingen . There were no discussion reports from the colleagues.

100th anniversary of death

The 100th anniversary of Alzheimer's death received attention in numerous lay and specialist media. Most of the contributions went into his life and work as well as the case of Auguste Deter, as well as the still inadequate diagnosis and therapy.

The Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy of the University of Munich held a conference on December 19, 2015 in memory of Alois Alzheimer, who worked at this clinic and continued the research on Auguste Deter there.

On the 100th anniversary of his death, there was a staged reading at the Tübingen Zimmer Theater entitled The Auguste D files. The texts were written by the neurologist Konrad Maurer - he discovered these files in 1996 - and his wife Ulrike. The reading was arranged by Michael Hanisch; the dramaturge was Ulrike Hofmann. The play had already been shown 15 years earlier at the Neumarkt Theater in Zurich, as well as on the 100th anniversary of Auguste Deter's death in Frankfurt.

Memorials and names

In 1995, on the 80th anniversary of his death in Marktbreit, an Alois Alzheimer's memorial and conference center with a small museum in four rooms was set up in his birthplace at Ochsenfurter Straße 15a.

The Clinic for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy at the University of Munich, Nussbaumstrasse 7, has a collection of psychiatric history in the Alois-Alzheimer-Saal, which also includes evidence of Alzheimer's and its time.

In Weßling, where Alzheimer lived during his time in Munich, there is an Alzheimergaßl near the Weßlinger See. Dr.-Alois-Alzheimer-Strasse is named after him in the new housing area in the city of Marktbreit.

In the ulica Odona Bujwida 42 (formerly Auenstrasse 42) in Wroclaw a plaque has been commemorating his work there since 1995.

The German Alzheimer's Society has branches in numerous German cities.

A large plaque in honor of Alzheimer's has been on the Westend campus of the Goethe University in Frankfurt am Main since 2005.

At Tübingen Hafengasse 6 there is a plaque commemorating Alzheimer's stay here as a student in 1886/87 as well as his first public presentation of senile dementia, "Alzheimer's disease", in the Tübingen mental hospital.

Fonts

In his work, Alzheimer's deals with the topics of progressive paralysis, arteriosclerosis of the brain, alcoholism and epilepsy.

- More recent work on dementia senilis and brain diseases based on atheromatous vascular disease , in: Monthly Journal for Psychiatry and Neurology 1898; 3, pp. 101–115 ( digitized version )

- with Franz Nissl: Histological and histo-pathological work on the cerebral cortex with special consideration of the pathological anatomy of mental diseases. 6 volumes, Jena 1904–1918.

- About a strange disease of the cerebral cortex . In: General journal for psychiatry . Volume 64 (1907), pp. 146-148.

- The war and the nerves . Preuss & Jünger, Breslau 1915.

literature

- Georg Stertz: Alzheimer's, Alois. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 1, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1953, ISBN 3-428-00182-6 , p. 236 ( digitized version ).

- Konrad and Ulrike Maurer: Alzheimer's - The life of a doctor and the career of a disease ; Piper, Munich 1998 ISBN 3-492-04061-6 ; Piper Paperback 2000 ISBN 3-492-23220-5

- Anne Eckert: Alois Alzheimer and Alzheimer's disease . Pharmacy in our time 31 (4) 2002 ISSN 0048-3664 pp. 356-360

- Michael Jürgs : Alzheimer's. Searching for clues in no man's land . List Taschenbuch, Munich 2001 = ISBN 3-548-60019-0 ; ibid. 1999 = ISBN 3-471-79389-5

- German E. Berrios: The history of 'Alzheimer's disease'. Archived version ( Memento of December 17, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Axel W. Bauer : Alzheimer, Alois. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin 2005 ISBN 3-11-015714-4 p. 49

- Jay Ingram: The End of Memory: A Natural History of Aging and Alzheimer's. Thomas Dunne Books / St. Martin's Press, 2014

Web links

- Literature by and about Alois Alzheimer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Ansgar Fabri, Annette Baum: Biography of Aloysius Alzheimer , Biographical Archive of Psychiatry (BIAPSY), 2015

- Manuel B. Graeber: Biography at the International Brain Research Organization (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Kösener Corpslisten 1930, 138 , 524

- ↑ Preußische Allgemeine Zeitung, No. 43, October 24, 2009, p. 21

- ↑ GenWiki: Alois Alzheimer

- ↑ Sabine Schuchert: Creutzfeldt and Jakob were both on the trail of a riddle Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2019, Volume 116, Issue 49 of December 6, 2019, page (60), link accessed on December 15, 2019, 9:18 p.m. CEST

- ↑ Auguste D. ( Memento from January 1, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) From: Alzheimer Info. 02/1997. Website of the German Alzheimer's Society, accessed on January 1, 2017.

- ↑ Alois Alzheimer: On the 100th anniversary of his death pharmische-zeitung.de, December 21, 2015

- ↑ Kathrin Zinkant: In search of an Alzheimer's drug sueddeutsche.de, December 19, 2015

- ↑ Andrea Schorsch: Discovery of a disease: Alois Alzheimer and the great forgetting n-tv.de, December 19, 2015

- ↑ Martin Harth: Marktheidenfeld: Where Alzheimer's uncle taught mainpost.de, December 20, 2015

- ↑ Martin Bernklau: Staged reading: »I've lost myself« Reutlinger General-Anzeiger, December 22, 2015

- ↑ Eckart Roloff and Karin Henke-Wendt: Visit your doctor or pharmacist. A tour through Germany's museums for medicine and pharmacy. Volume 2. Hirzel, Stuttgart 2015, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Eckart Roloff and Karin Henke-Wendt: Visit your doctor or pharmacist. A tour through Germany's museums for medicine and pharmacy. Volume 2. Hirzel, Stuttgart 2015., pp. 124–126.

- ↑ https://www.deutsche-alzheimer.de

- ↑ Memorial plaque for Alois Alzheimer , website of the Goethe University Frankfurt am Main, accessed on January 8, 2018.

- ↑ Picture and explanation on the municipal Tübingen page

- ↑ Information on the location of the "Tübingen Wiki"

- ↑ Lilly Deutschland GmbH (Ed.): Alois Alzheimer's birthplace. Memorial and conference center in Marktbreit am Main near Würzburg. Brochure from around 2014.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Alzheimer's, Alois |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German psychiatrist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | June 14, 1864 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Market wide |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 19, 1915 |

| Place of death | Wroclaw |