Brown shrike

| Brown shrike | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Brown Shrike ( Lanius cristatus ), |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Lanius cristatus | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

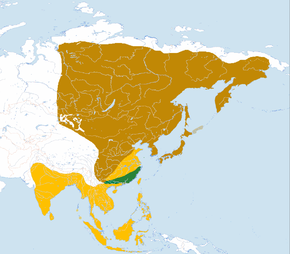

The brown shrike ( Lanius cristatus ) is a songbird belonging to the genus of the real shrike ( Lanius ) within the family of the shrike (Laniidae). The rather small shrike with a fairly uniform reddish-brown or gray-brown appearance inhabits a very large area of distribution that extends from the Tropic of Cancer in the south to the Arctic Circle in the north. To the west the species reaches the foothills of the Altai in Kazakhstan , to the east the Japanese islands .

Most of the brown shrike are migratory birds , those of the Far North are extreme long-distance migrants . Only a few populations in southeast China remain in the breeding area throughout the year. The wintering areas are on the Indian subcontinent , in Indochina , in the Philippines and on most of the Indonesian islands .

Brown shrike feed mainly on insects and other invertebrates , but also prey on small vertebrates such as mice , lizards and birds . They inhabit different habitats, but mostly open, loosely bush or tree-lined landscapes.

The family position of the brown shrike within the genus is not sufficiently clarified. Usually it is placed in a superspecies together with the Isabella Shrike and the Red- backed Shrike. It also hybridizes with these two species in the extreme west of its range. It is also closely related to the tiger shrike , with which mixed breeds have also been found.

The species, of which four subspecies are currently recognized, is not listed in any endangerment category - despite some dramatic population losses, especially in Japan.

Appearance

With a size of about 18 centimeters and a weight of around 33 grams, the brown shrike is just as big and about as heavy as the red backed shrike , to which it is also similar in appearance. The sexes have no size or weight dimorphism, there is a color dimorphism, but not very clearly. Four subspecies are described, three of which do not differ very noticeably, the subspecies L. c. lucionensis shows significant differences in color. Brown shrike appear large and round-headed. They are of a relatively uniform brown color on the upper side and lighter, partly yellowish or orange puffy underside. In addition to the black face mask typical of a strangler, a pure white stripe over the eyes is striking , which is found in the subspecies L. c. superciliosus is particularly pronounced.

The crown, neck, coat, shoulders and rump are red or chestnut brown, the top of the stepped tail is slightly lighter, more reddish brown with a slightly darker end region, especially in males. A very narrow, but rapidly widening, black band runs from the upper beak base over the eyes to behind the ear covers , which forms the typical mask. It is bordered by a pure white stripe almost in the entire upper area, which additionally emphasizes the contrasting effect of the face mask. In the subspecies L. c. superciliosus , this band is particularly wide and also covers almost the entire forehead. The wings are dark brown, the large wing covers and the umbrella feathers are edged in light brown. A white coloration in the basal area of the hand wings is mostly missing or is only very indistinct, so that the brown shrike is one of the few species of shrike that do not show white wing markings in flight . The entire underside is colored matt white and varies in strength, especially on the flanks and in the lower abdominal region, yellowish or orange-yellowish tones. The mighty hooked bill is black in the males, rather horn gray in the females, the lower bill is lighter, often tinged with pink. Legs and toes are blue-gray, the iris is dark brown.

Females are colored very similarly. In general, the brown of the upper side is more matt, the face mask is narrower or only clearly drawn behind the eyes, the outer eye stripe is also narrower and often not pure white, but cream-colored. Often a fine banding in the chest area and on the flanks can be seen.

Juvenile brown shrike have dense cinnamon-brown banding on the matt brown-gray upper side, the face mask is brown and only recognizable behind the eyes, the stripe above the eyes is blurred and interrupted. The washed-out, light brownish underside is, with the exception of the lowest part of the abdomen, intensely darkly banded and sparged.

The brown shrike occurs in the western and southwestern part of its distribution area as well as in some wintering areas sympatric with the red-backed shrike and the Isabel shrike. Mixed broods with both species are documented. A reliable identification of young birds and immature females is very difficult in field ornithological terms .

Mauser

The moulting of the brown shrike is similar to that of the tiger shrike , but differs in the sequence of the large plumage change. Like the tiger shrike, brown shrike also molt their entire plumage twice a year. The post-breeding period moulting begins in the breeding area, immediately after - sometimes even towards the end - of the last brood. In birds in the southern breeding areas, i.e. in all resident populations and those who only cover short distances to winter quarters, this is a full moult that is still completed in the breeding area. In birds that breed in northern latitudes, or in very late broods, moulting is interrupted after the change of small plumage and some (individually different) large feathers and either continued and completed during extended breaks or only in the wintering areas. A second complete moult begins quite soon afterwards, usually at the end of December / beginning of January, and is completed when the migration home begins at the beginning of April / beginning of May. The juvenile moult begins at the age of 40–55 days and mainly affects the small plumage and only a few large feathers. It is also completed during intermediate stops during the train or when you reach the winter quarters. It is unclear whether all of this year's birds will completely moult their plumage again before they move home.

Vocalizations

Like most stranglers, brown stranglers are acoustically noticeable only in aggressive situations and in the phase of establishing territory and forming pairs. The singing can be heard almost exclusively in the pre-breeding season. The most common is a multiple, hoarse call that is similar to the red killer's alarm call. It is individually different and difficult to transcribe - most likely with zcha… zcha… . In a very high mood of aggression, a very clearly audible squire is woven into the call rows. In addition, staccato-like staccato tckack or avocal tck sounds serve as additional acoustic alarm signals. During the mating season, the female begs with jiih ... jiih ... - calls, the begging sounds of the nestlings . The singing is a very loud, warbling chirping. Melodic and structured phases are interrupted by whistles and elements from the alarm repertoire. Like many other species of shrike, the brown shrike also uses phrases from other bird songs and imitates a wide variety of noises.

distribution

The brown shrike colonizes a very large area that extends north-south from areas beyond the Arctic Circle at around 70 ° north south to the southeastern Chinese breeding areas at the Tropic of Cancer, which almost touches the tropics. Along with the northern gray shrike, it is one of the species of shrike that has succeeded in opening up very different climatic zones and penetrating very far north. The western limit of the distribution is unclear, possibly also subject to certain fluctuations. Generally it is set at 80 ° East; in the south-west it reaches the Russian and Mongolian Altai and the northern Nan Shan in the four-country border area of Russia, Kazakhstan , Mongolia and China . The contact zones with the red-backed shrike (especially in the Djungarian Alatau ) and the Isabellian shrike (in Dauria and the Mongolian Altai) are in this greater area . In the east, the western half of Kamchatka , Sakhalin , some islands of the southern Kuril Islands and, in a rapidly decreasing density, Hokkaidō , Honshū and Kyūshū - as well as some of the smaller Japanese islands - are inhabited by this species.

The wintering areas are located south of it in southeast China, Indochina , on the Malay Peninsula , the Philippines , many of the large and small islands of Indonesia , as well as on the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka .

habitat

The brown shrike can breed successfully in very different habitats . Overall, it belongs to the species of strangler with a very large habitat tolerance. Nevertheless, in this extensive range, regional populations are closely tied to certain habitats, which, in combination with the rather high loyalty to the breeding site, makes the species very susceptible to changes in habitat.

A preference for loosened bush or tree-covered habitats with as little or only a short amount of vegetation as possible is always to be determined. The species does not colonize closed, contiguous forest areas, but occurs in extensive natural clearings or clearings created by logging, in early succession vegetation after forest fires and on forest edges, provided that these border areas that are favorable for prey acquisition. In the taiga / tundra transition zone, the species breeds mainly in loose birch stands , to the south - in the central Siberian regions - in pastures along small rivers. Gallery vegetation accompanying the river offers suitable breeding opportunities in the arid regions of western and south-western China and Mongolia. In the Altai area , regions with individual larches and juniper bushes often form favorable habitats. The species often colonizes windbreak plantings on the edge of cultivated land, rows of trees along streets, and occasionally parks and very large gardens. The subspecies L. c. In Japan, superciliosus prefers light oak forests near the coast or pasture and grassland with deutzia . The most southerly distributed subspecies L. c. lucionensis often breeds in the border zones of subtropical and tropical evergreen forests as well as in secondary vegetation after logging. This subspecies also appears most frequently in heavily man-made landscapes, especially in agricultural areas.

Vertically, the species is mainly represented in the lowlands and in the hill country below 1000 meters, in the southwest of the distribution area it occurs up to heights of 1800 meters, in the wintering areas also at slightly higher altitudes.

Settlement densities

The population densities are subject to strong regional and temporal fluctuations. In general, however, there is also a negative stock trend across all areas. In very favorable habitats, for example on open areas after forest fires in early succession vegetation or in regions with a mass increase in forest pests, especially from the genus Dendrolimus , the brown shrike reaches very high population densities with 80 breeding pairs / km². In such areas, the nest distance can be 70 meters or less. Usually, however, the population density is much lower and the nest spacing of around 300 meters is significantly greater, even in habitats that are favorable for the species. The largest population densities of the subspecies L. c. superciliosus in Japan are given as 1–2 breeding pairs / hectare .

hikes

The migrations of the brown shrike have not yet been adequately researched, but the studies carried out so far indicate that the individual subspecies seek out wintering areas that are separate from one another, but which overlap in their border areas on a large scale.

Except for a relatively small distribution area in southeast China and possibly in the south of the Korean Peninsula , which is inhabited by mostly resident populations, brown shrike are obligatory migratory birds , those of the nominate form often long-distance migrants, whose wintering areas are mainly in India and in the western part of Indochina. From west to east and south-east those of L. c. confusus , L. c. lucionensis and L. c. superciliosus on it. Some populations travel up to 700 kilometers non-stop over the open sea.

The migration of the breeding birds in the far north begins at the end of July and reaches its peak around mid / end of August. The birds from more southern regions move away later, but most of the breeding areas are completely cleared by the end of September. The return of brown stranglers of the subspecies L. c. lucionensis begins in mid-March, that of the nominate form a good month later. Most of the breeding sites are occupied by the end of May or mid-June at the latest.

Brown shrike migrate individually or in very small groups - especially during the night and in the first hours of the morning. They spend the day resting, looking after their feathers and looking for food. Longer breaks are often taken during the move, and the return home is quicker. Adult birds leave the breeding area first, young birds one to two weeks after them. In the breeding areas, the males often appear a little before the females.

Food and subsistence

Like all stranglers, brown shrike are food opportunists . They prefer larger invertebrates , especially insects , but when there are large numbers of them , they also collect small species, the species or genus of which can no longer be determined later in the spitting balls . Among the insects, grasshoppers , catching terror , crickets , cicadas , beetles , butterflies and their caterpillars , dragonflies and hymenoptera , including stinging species, predominate . Vertebrates such as nestlings and small passerine birds , mice , frogs, and reptiles such as geckos , lizards, and agamas are occasional prey; as suppliers of food they apparently play a greater role in the winter quarters than during the breeding season.

Brown shrike are hunters of waiting . After a very extensive investigation, 89% of all successful hunting attempts were made with this method. The vast majority of prey animals (almost 60%) are struck within a radius of 1.5 meters, the furthest observed distance of a successful attack was 22 meters. The height of the seat depends on the height and density of the undergrowth. Usually it is around 2 meters, but is lower when the undergrowth is thicker and higher.

In addition to high-seat hunting, brown shrike search substrate surfaces for prey, hunt for large insects in flight and - especially during migratory times - attack small migratory birds that migrate in flocks like little hawks .

Brown shrike store supplies by skewering and pinching in branch forks. The vast majority of the prey stored in this way are vertebrates. Fejervarya limnocharis - a small species of frog common in South and Southeast Asia - and relatives from this species complex are found particularly frequently on the spit-pit. Prey animals that are not eaten immediately transport brown shrike in their beak to the spit or feeding place.

behavior

Brown shrike are mainly diurnal, but sometimes hunt in the first hours of the night on bright nights. Outside of the breeding season they live largely solitary, during the breeding season in a seasonal pair bond. Their behavior is very similar to the red-backed shrimp, but overall they are a little less noticeable and more hidden than this. They claim both breeding and non-breeding season territory, which is vigorously defended against conspecifics, other shrike species and against food competitors. With the buffalo head shrike they also occur in very closely adjoining, sometimes overlapping areas. The aggression and warning signals consist of loud series of calls, inspection flights at the territorial borders and - when an adversary comes closer - in the assumption of a very upright posture, described as a pole position, which changes into the hump position with beak pointing and wilting tail when the pressure of aggression persists. This highest level of aggression can be followed by direct contact fights. In the case of strangler pairs, females usually only take part in these arguments with their voices.

Brown shrike quietly flee from enemies of the air into thick bushes; Nest robbers, especially magpies , are attacked directly and also bullied outside the breeding season . Brown shrike recognize different cuckoo species as brood parasites and try to drive them out of the nest environment.

The loyalty to the breeding site is particularly pronounced in the males. An extensive study found that 43% of last year's successful breeders returned to the nesting site, compared to only 13% of the females.

Breeding biology

Most males appear before the females in the breeding area, so that there is a great shortage of females in the breeding areas for a few weeks. During this time courtship rituals between sexually high-spirited males were observed. After the arrival of the females, the actual courtship and pairing takes place within a very short time. The most important courtship elements, in addition to the sightseeing flights and chants, are the posture of the male in the immediate vicinity of the female, with the male performing violent head rotations, accompanied by a soft murmuring song. After a certain time, the female performs similar movements - often in sync with the male. The handover of food reinforces the bond, whereupon the female usually slips into thicker bushes, where the first copulations take place.

The nest is built by both partners within a week, but most of the work is done by the female. The nest carriers are different bushes or trees, twelve different species were found in the Ussuri region alone. The nest height is on average around 2 meters. It is not uncommon for brown shrike to build their nest on the ground, usually within a cushion of grass under bushes, a behavior that has only been observed in a few stranglers - among them the red-backed shrike. The nest itself is a rather untidy, unstable-looking structure, which consists of an outer framework of branches and an inner bowl made of grass, stems, tendrils and strips of bast. The outside is often covered with moss and leaves, while the inside is mainly covered with animal and plant wool. The outside diameter varies between 115 and 130 millimeters, the inside diameter averages 80 millimeters. The depth of the bowl is around 55 millimeters.

The clutch consists of 4–6 (3–8) eggs of a matt white, pink or greenish basic color. Especially at the blunt end, they are speckled brown, gray or purple. The egg size of the nominate shape is 22.8 × 17.3 millimeters. The average clutch size increases with latitude. The smallest eggs and the smallest clutches were found in the largest and most widespread subspecies L. c. lucionensis . In the north, the main laying period begins in mid-June and lasts until the end of July, in the more southerly breeding areas it begins a little earlier and lasts until August. The first clutches are found in southern Japan and south-east China towards the end of April. The majority of the brown shrike only breed once a year, but replacement broods are the rule when the clutch is lost. In the southernmost breeding areas, many pairs breed twice a year.

The clutch is incubated almost exclusively by the female for about 15 days (13-16); during this time and in the first week after hatching, the male largely supplies it with food. The young hatch naked and blind, but develop very quickly and leave the nest after 13-14 days. They initially remain in the immediate vicinity of the nest, where they are further fed by the adult birds. With increasing independence, they move further away from the nest location, but usually remain within a radius of 800 meters until the first move.

The breeding and nestling losses due to weather influences and nest predation are very large. The departure rate is correspondingly low. Influences of an anthropogenic nature also seem to have a negative impact: In 1975 it was 75% on a test area on Hokkaidō, but only 29% in 1996.

Systematics

The brown shrike is generally placed in a superspecies with the red backed shrike and the Isabel shrike. With both, there are mixed broods in the contact zones of the three species, of which at least those with the red-backed shrimp do not show any hybridization reductions in relation to clutch size and breeding success and the offspring are apparently fertile . Mixed broods with the Isabellus shrike are less common, and nothing is known about their fertility. Mixed broods of brown shrike and tiger shrike have been found in some regions of Japan, in the Primorye area of the extreme south-east of Russia and possibly in the north of the Korean peninsula. In all hybrid broods, only the heterospecific parent pair has been observed during brood care; genetic analyzes of the nestlings are not available. Mostly the female was a brown shrike. Copulations of extra pairs do occur in brown strangles, so fertilization of the eggs by a conspecific cannot be ruled out.

There is currently only one study on the phylogenetic position of the brown shrike within the genus, which takes eight species of shrike into account. According to this, red-backed shrike and Isabellus shrike are sister species , while brown shrike and chess shrike , or buffalo-head shrike and Tibetan shrike form parallel clades in direct genetic proximity.

Four subspecies are recognized that differ clinically in terms of the size and color of the upper plumage. The smallest subspecies is the nominate form, the largest L. c. lucionensis :

- Lanius cristatus cristatus Linnaeus , 1758: Northern, western, central and northeastern part of the distribution area.

- Lanius cristatus superciliosus Latham , 1801: South Sakhalin, South Kuril Islands, North and Central Japan. Very broad white stripe above the eyes, half white forehead. Rich red-brown colored upper side; Wings rather dark gray.

- Lanius cristatus lucionensis Linnaeus , 1766: South Japan, Korea, Southeast China. Largest subspecies. Gray to gray-brown on the upper side, only tail-coverts and tail reddish-brown. The white stripe above the eyes is barely noticeable. Forehead light whitish-gray, flanks quite an intense yellow-orange tint.

Persistence and Threat

The stock situation of the brown shrike is confusing, but is rated by the IUCN with LC = no risk ( least concern ).

For many areas, especially in the core zones in Siberia, there are no current inventory analyzes. Overall, however, there is a negative trend that has taken on dramatic dimensions in some areas, such as the Amur - Ussuri region, but above all in Japan. In Japan the subspecies L. c. superciliosus is affected by population collapse, which in some areas has exceeded 80% in the last 20 years. The status of L. c. lucionensis in southern Japan is unclear. The reasons given for the decline are habitat loss, increased insecticide input, but also the persistent persecution of the species in the wintering areas. It is noteworthy that the buffalo head shrike, which occurs regionally with the brown shrike in the same habitats, was not only able to maintain its population density, but even increase it.

Like all small and medium-sized passerine birds, the brown shrike also has a large number of natural enemies, especially birds of prey and crepuscular and diurnal owls , especially the hawk owl . The breeding success is reduced by some nest predators , especially by martens , by crows , by house cats in the vicinity of settlements, in the more southern distribution areas also by snakes and by breeding parasites. A total of four cuckoo species parasitize the brown shrike, among which the short-winged cuckoo has largely synchronized its laying times with the breeding times of the brown shrike.

literature

- Tony Harris, Kim Franklin: Shrikes & Bush-Shrikes. Including wood-shrikes, helmet-shrikes, flycather-shrikes, philentomas, batises and wattle-eyes. Christopher Helm, London 2000, ISBN 0-7136-3861-3 .

- Josep del Hoyo , Andrew Elliot, Jordi Sargatal (Eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 13: Penduline-Tits to Shrikes. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2008, ISBN 978-84-96553-45-3 .

- Yosef, R. & International Shrike Working Group (2008): Brown Shrike (Lanius cristatus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, DA & de Juana, E. (eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 2014. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/60472 on December 5, 2014).

- Evgenij N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) of the World - Ecology, Behavior and Evolution. Pensoft Publishers, Sofia 2011, ISBN 978-954-642-576-8 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d T. Harris, K. Franklin: Shrikes & Bush-Shrikes ... 2000, p. 187.

- ↑ a b c d e f Reuven Yosef & International Shrike Working Group (2008). Brown Shrike (Lanius cristatus) . In: Josep del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. Christie, and E. de Juana: (Eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive . Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. 2014. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/60472 on December 10, 2014).

- ↑ a b c Lanius cristatus in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014.3. Listed by: BirdLife International, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ↑ a b E. N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 620-621.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 612–614.

- ↑ a b c d e f g T. Harris, K. Franklin: Shrikes & Bush-Shrikes ... 2000, p. 189.

- ↑ xeno-canto: sound recordings - brown shrike ( Lanius cristatus )

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 618–622.

- ^ A b E. N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 601.

- ↑ a b c d e f g T. Harris, K. Franklin: Shrikes & Bush-Shrikes ... 2000, p. 188.

- ^ A b E. N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 602-603.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 596–601.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 600.

- ↑ a b c E. N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 601-603.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 602.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 604.

- ↑ a b c d e f E. N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 617.

- ^ A b E. N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 606.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 618–619.

- ^ A b E. N. Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 605.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, pp. 606-608.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 607.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 608.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 610.

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 621.

- ↑ Wei Zhang, Fu-Min Lei, Gang Liang, Zuo-Hua Yin, Hong-Feng Zhao, Hong-Jian Wang, Anton Krištín: Taxonomic Status of Eight Asian Shrike Species (Lanius): Phylogenetic Analysis Based on Cyt b and CoI Gene Sequences . In: Acta Ornithologica . tape 42 , no. 2 , December 2007, p. 173-180 , doi : 10.3161 / 068.042.0212 .

- ↑ a b Masaoki Takagi: Philopatry and habitat selection in Bull-headed and Brown shrikes . In: Journal of Field Ornithology . tape 74 , no. 1 , 2003, doi : 10.1648 / 0273-8570-74.1.45 .

- ↑ EN Panov: The True Shrikes (Laniidae) ... 2011, p. 619.

Web links

- Lanius cristatus inthe IUCN 2013 Red List of Threatened Species . Listed by: BirdLife International, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2014.

- Feathers of the brown shrike