The Fiesco conspiracy in Genoa

| Data | |

|---|---|

| Title: | The Fiesco conspiracy in Genoa |

| Genus: | A Republican tragedy |

| Original language: | German |

| Author: | Friedrich Schiller |

| Publishing year: | 1783 |

| Premiere: | 1783 |

| Place of premiere: | Hof theater Bonn |

| Place and time of the action: | Genoa, 1547 |

| people | |

|

|

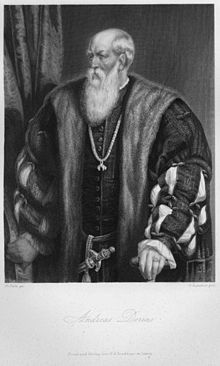

The Fiesco conspiracy at Genoa is Friedrich Schiller's second completed drama . He began it after the premiere of Die Räuber in 1782 and dedicated it to his teacher Jakob Friedrich von Abel . The play called “A Republican Tragedy”, which is based on the historical conspiracy of Giovanni Luigi de Fieschi against Andrea Doria in Genoa in the spring of 1547, was premiered in 1783 at the Bonn court theater.

Emergence

When Schiller fled from Stuttgart to Mannheim on September 22, 1782, he carried in his luggage the almost finished manuscript of a play which, according to his own statement, he sought to give a completion that has never been seen on German stages. A piece that shouldn't be distorted by any of the flaws that still clung to its first piece. With the conspiracy of Fiesco , which he wanted to present to none other than Gotthold Ephraim Lessing , Wieland and Goethe before publication , which he then failed to do , the young Schiller was convinced that he would truly establish his reputation as a dramatic writer.

On September 27th the author read his play in front of the actors of the Mannheim theater in the house of the director Wilhelm Christian Meyer. Schiller's escape companion Andreas Streicher reported on that afternoon. The audience's reaction was devastating. By the end of the second of the five acts at the latest, the company had got lost except for Meyer and Iffland. On leaving, the director asked Streicher whether he was sure that it was really Schiller who wrote the robbers : “Because Fiesko is the very worst thing I've ever heard in my life, and because it is impossible for the same Schiller who wrote the robbers, should have done something so mean and wretched. "

Streicher gave him the manuscript. Meyer read it that night and completely revised his opinion of the previous day. What made the piece seem so bad on him was only the author's Swabian pronunciation and the “cursed way he declaims everything” - a gift that Schiller himself gave a lot. "He says everything in the same high-pitched tone, whether it means: he closes the door or whether it is a main part of his hero." The drama itself had convinced Meyer. "Fiesko," he said, "is a masterpiece and worked far better than the robbers!"

Schiller's understanding of historical truthfulness on stage

While working on his Fiesko, Schiller had immersed himself in historical accounts, he had pored over trade statistics and studied documents from the everyday culture of that time in order to come close to the historical veracity of the conspiracy of 1547, which interested him already at the time of writing his third dissertation; for similar reasons, apparently like Sallust 's conspiracy of Catiline , whose words he quotes at the beginning of the piece: Nam id facinus inprimis ego memorabile existimo sceleris atque periculi novitate. (For I consider it a company whose record is immensely serviceable, alike because of the unusual nature of its guilt and dangers.)

Unlike the historian Sallust, however, Schiller did not deal with historical events in order to bring them closer to the audience in this very way, but rather to give his dramatic character experiments a historically probable background. The theatrical effect of probability was more important to him than historical truthfulness. In the gossip in the stage version, Schiller makes this point of view clear, to which it is also owed that he interprets the conspiracy as well as the death of Fiesko very freely:

“I dare to deal with history soon, because I am not his [Fieskos] historian, and a single great surge, which I cause in the breasts of my audience through daring fiction, outweighs the strictest historical accuracy. "

The plot

Genoa 1547 . The trading metropolis had received its independence from France and a new prince 19 years earlier through Andrea Doria . But the Doge Doria is now an old man of 80 years. It is to be feared that his nephew Gianettino Doria will soon be his successor. But among the Nobili Genoas there is resistance to Doria's rule and especially to his tyrannical nephew. Around the iron-hard Republican Verrina, a few displeased people have rallied, most of whom pursue selfish goals. Sacco joins the conspiracy because he believes he can get rid of his debts through an uprising, Calcagno wants to conquer Fiesco's wife Leonore, Bourgognino finally wants to bring home his bride Bertha, Verrina's daughter. Her seduction and rape by Gianettino Doria finally gives rise to the immediate conspiracy. The young Fiesco, Count von Lavagna, for his part, behaves in such a way that the conspirators cannot be sure whether he belongs to them. He woos the notorious sister of the scheming Gianettino and generally acts as an unprincipled bon vivant without any political ambition. Even Leonore, Fiesco's wife, doesn't know where her husband is. Verrina alone distrusts the Count's behavior. He suspects the conspirator behind the mask of the connoisseur, so fears Fiesco and decides to move him out of the way as soon as the conspiracy is over and Genoa is freed. Gianettino Doria also sees a danger in Fiesco and wants the Moor Muley Hassan to remove him. However, the murder is betrayed by the Moor and Fiesco gets the man at hand with whose help he can set off his intrigue. Now he reveals his own secret preparations for a coup to the other Nobili, but does not let them in on all the secrets. He is immediately recognized as the head of the conspiracy. Only Verrina remains suspicious. He fears that Fiesco is not aiming for a republic but for ducal status. In a confidential scene in the forest, he reveals his concerns to his soon-to-be son-in-law Bourgognino; for him it is clear: "If Genoa is free, Fiesco dies."

Schiller spins a threefold conspiracy in his tragedy: Gianettino is preparing a coup that will disempower Andrea Doria and destroy the remaining Republicans without exception. Fiesco's conspirators are overthrowing Dorias and Verrina, worried about the republic, and if the conspiracy is successful, they plan to kill Fiesco.

And Verrina's concern is not entirely unfounded, because Fiesco is in the dark about his future and the Genoas: “What an uproar in my chest! What insidious escape of thoughts [...] Republican Fiesco? Duke Fiesco? […] "After a pause for thought, firmly:" Fighting for a diadem is big. Throwing it away is divine. "Determined:" Go under tyrant! Be free, Genoa, and I ”- gently melted -“ your happiest citizen! ”Only his happiest citizen? One appearance later, Fiesco is more insecure than ever: “That I'm the tallest man in all of Genoa? and shouldn't the little souls gather under the big one? "

He is determined. The conspiracy takes its course. Under the pretext of equipping several galleys for a train against the Turks, Fiesco collects several hundred mercenaries and smuggles them into the city. Under his leadership, the conspirators occupy the gate of St. Thomas, take the port by surprise and seize the galleys and the main squares of the city. The young Bourgognino takes revenge on Gianettino Doria for the desecration of his bride by stabbing him as he swore. Andrea Doria flees. The city seems entirely in Fiesco's hands, but the confusion is still great. Leonore and her servant Arabella, contrary to her husband's prohibition, went into the city in men's clothing. She follows the action proudly and heroically. She finds the dead Gianettino and throws on his purple cloak in wild enthusiasm. Fiesco, seeing her rushing through the streets, takes her for a Doria and strikes her down. The knowledge that he has murdered his beloved wife, with whom he wanted to share his glory, plunges him into deep despair. But he collects himself quickly. “Providence, I understand your hint, did this wound only strike me to test my heart for near greatness? […] Genoa await me, you say? - I want to give Genoa a prince the likes of which no European has ever seen - Come! - I want to hold a funeral for this unfortunate princess so that life should lose its worshipers and rot should shine like a bride - Izt follows your duke. "

In fact, Genoa is ready to cheerfully recognize Fiesco as the new Duke. Verrina alone follows his oath. Using a pretext, he lures Fiesco to the sea, where he first wistfully, then kneeling, begs him to take off the purple again. Fiesco remains tough. Verrina then pushes the prince into the sea. The heavy purple cloak pulls him down. Conspirators arrive shortly afterwards with the news that Andrea Doria has returned. They ask about Fiesco's whereabouts. “Drowned”, Verrina replies, “Drowned, if that's prettier - I'll go to Andreas.” Everyone stops in rigid groups while the curtain falls.

So much for the book version. In the stage version there is a different, but no less likely ending. Here Fiesco conquered Genoa to return it to the hands of the Republic. With the words “Fighting for a diadem is great. Throwing it away is divine ”, he breaks the scepter of sole rule and proclaims the freedom of Genoa. Fiesco and Verrina fall into each other's arms, crying.

Fiesco and the adventure of freedom

"True greatness of mind", wrote Schiller in 1788 in the eleventh of his twelve letters to Don Karlos , "often leads to violations of foreign freedom no less than egoism and lust for domination, because it is about the action, not the sake of the individual subject."

The greatness of character was always something attractive to Schiller, the admirer of Plutarch's ancient biographies . This also applied to the figure of the Count of Fiesque. Historical tradition describes him as strong, beautiful, cunning, loved by women, of a proud noble family and irrepressible political ambition. But it is unclear whether he wanted to liberate the republic from princely rule or establish one of his own. As a Renaissance nature, he stands beyond good and evil. The greatness of his character made him a hero for Schiller, regardless of whether it was virtuous or criminal.

In the afterword of the Mannheim stage version he writes:

"Fiesco, a great, terrible head who, under the deceptive shell of a soft, epicurean idler, in quiet, noiseless darkness, like the child-bearing spirit on the chaos, lonely and unobserved, hatches a world and lies the empty, smiling face of a good-for-nothing, while that huge tarpaulin." and furious desires ferment in his burning bosom - Fiesco, who, misunderstood long enough, finally emerges like a god, presents the mature, finished work in front of astonishing eyes and stands there a calm spectator when the wheels of the great machine run infallibly towards the desired goal. "

With his hero, Schiller wanted to bring a figure to the stage that could not be grasped, a person of brilliant impenetrability, who is so free that it includes both possibilities, that of the tyrant and that of the liberator from tyranny. Schiller began working on his piece without having decided on one of the options. Had he made up his mind, he would have known how the piece should end. But he didn't even know that when everything was finished, except for the last two scenes. So Fiesco doesn't know how to act until the end, because Schiller didn't know how to let him act. Fiesco remains undecided, and so did Schiller; until the beginning of November 1782, when he finally gave the piece the two different outcomes described above. Both are absolutely conclusive because Fiesco is free enough to choose either course of action. In this context, Schiller told his friend Andreas Streicher that the last two scenes “cost him far more thinking” than the rest of the piece.

In his biography, Rüdiger Safranski draws the conclusion at this point that Schiller, the “enthusiast of freedom”, in his Fiesco is not about the question of how one should act, but what kind of action one actually wants. "It's not about what you should want, but what you want," says Safranski, "Freedom is that in people that makes them unpredictable, for themselves and others."

In his robbers , Schiller had “taken the victim of extravagant feelings as a reproach”. In Fiesco he tried “the opposite, a victim of art and the cabal”. In his preface he expressed concerns about the stage suitability of “cold, sterile state action”: “If it is true that only sensation arouses sensation, then it seems to me that the political hero should not be a subject to that degree be for the stage in which he has to put people behind in order to be the political hero. "

The piece gained enormous popularity with an astonishing 75 performances. Today, however, in contrast to the robbers or cabal and love, it is rarely staged. One reason for this could be Schiller's relationship to democracy. In the eighth appearance of the second act, he depicts a “crowd scene” with twelve (!) Craftsmen. They know exactly what they don't want (the establishment of absolutist conditions in Genoa), but not what they should aim for instead. In their perplexity they turn to Fiesco, who is supposed to “redeem” them. He tells them a fable in which the rule of the butcher's dog is replaced by that of the lion (i.e. the rule of the Dorias by the Fiescos). Fiesco dissuades the craftsmen from their desire to establish a democracy by pointing out that democracy is “the rule of the figs and the stupid”, since there are more cowards than the brave and more stupid than the clever and that the majority principle prevails in democracy. With their jubilation, the craftsmen confirm Fiesco's judgment, who then weighs himself in euphoric certainty of victory. The view that democracy is a "rule of the figs and the stupid" and therefore the rule of a "good prince" is preferable to it is today considered unacceptable, but was still widespread in Schiller's time, especially through the reception of Plato's Politeia ( State), with which Plato wants to show, among other things, that it is ultimately best for all members of a society when those who are best suited to rule rule. And Plato thinks that this is only a small minority. The majority is better suited for other tasks, e.g. B. National defense, trade or craft. So if everyone does exactly what they are best able to do, then this is the best for everyone in the long term, Plato has Socrates explain. This attitude can also be read in Schiller's song from the bell : "The master can break the shape / With a wise hand at the right time / But woe when in torrents / The glowing ore frees itself!"

Fiesco's problem is also that he is perhaps more of the “fox” than the “lion” (the “masterful” and therefore legitimate ruler of the fable), so the question arises whether he is really better than the “butcher's dog”. Fiesco himself wavers between republican and monarchical ideals, and at the insistence of his wife Leonore, almost gives up his lust for power in favor of love and a bourgeois family life, but only almost. He is a tragic hero in the sense of Aristotle insofar as he too has flaws, and in the original conclusion these actually become his undoing and he is murdered. In the later stage version, Schiller transformed the tragic ending into a surprisingly pleasant one, in that Fiesco renounced his principality and the monarchy became a republic. After 1790 this was interpreted as a pro-revolutionary plea and the piece was therefore often banned in this version.

Radio plays

- The Fiesco conspiracy in Genoa . GDR 1969. Composition: Reiner Bredemeyer , director: Peter Groeger .

Settings

- Friedemann Holst-Solbach: Fiesco. The Fiesco conspiracy to Genoa, partly set to music and underlaid. Libretto by the composer. Setting to music in twelve-tone technique. The orchestration follows the Pierrot Lunaire by Arnold Schönberg . Piano reduction: 141 pages including a fourteen-page libretto with suggestions for direction, ISMN 979-0-50072-613-5 (search in the DNB portal) .

literature

- Julius Bacher : The historical Fiesco . In: The Gazebo . Issue 46–47, 1866, pp. 725-727, 735-737 ( full text [ Wikisource ]).

- Matthias Luserke-Jaqui : Friedrich Schiller (= UTB 2595 literary studies ). A. Francke, Tübingen a. a. 2005, ISBN 978-3-7720-3368-1

- Rüdiger Safranski : Friedrich Schiller or The Invention of German Idealism. Hanser, Munich a. a. 2004, ISBN 978-3-446-20548-2

Web links

- The Fiesco conspiracy to Genoa in Project Gutenberg ( currently not available to users from Germany )

- The Fiesco conspiracy to Genoa in the Gutenberg-DE project

- The Fiesco conspiracy to Genoa at Zeno.org .

- Synopsis, characterization of the characters, origin and text of the piece in the Friedrich Schiller Archive

- The Fiesco Conspiracy as a free audiobook in the public domain at LibriVox