Knight Toggenburg

Knight Toggenburg is a ballad by Friedrich Schiller composed in July of the ballad year 1797 . According to Schiller's calendar entry, he closed it on July 31. The poem, composed in ten trochaic stanzas , first appeared in the same year in the Muses' Almanac for the year 1798 and was also included in the poem editions of 1800 and 1804.

content

The poem tells the unattainable love of the knight Toggenburg. He joins a crusade and on his return learns that his beloved has entered a monastery . He settles down as a hermit within sight of her cell . He is satisfied that her image is shown to him in the distance. The ballad ends with his death. The conclusion is:

And so he sat, a corpse, there

one morning,

After the window still saw the pale,

still face.

effect

Today the ballad is hardly known to everyone. As the abundance of testimonials to be presented (including the rather trivial ones) shows, the poem was one of Schiller's most popular ballads, at least in the 19th century.

The following compilation can claim to be the most comprehensive documentation of the reception since the bibliographies by Wurzbach von Tannenberg and Wenzel, published in 1859 .

Immediate recording 1797/98

On September 12, 1797, Goethe wrote in a letter to Schiller I must not forget to congratulate Knight Toggenburg on the happy progress of the Almanac. (He had met her in the poster form of the Muses Almanac.)

On January 19, 1798, Christian Gottfried Körner , the poet's trusted friend and admirer, was the most detailed . Knight Toggenburg is particularly dear to me because of a certain musical unity and the consistent consistency of the tone, which perfectly matches the subject matter.

Karl Theodor von Dalberg , later elector and archbishop of Mainz , wrote a letter from Erfurt on November 21, 1797 , with an appreciation of the almanac ballads (ibid. 37th volume. Part I, 1981, p. 175). Abstract:

“In horrific ballads, the limited person wrestles with an all-powerful fate. The threatened, suffering, daring mortals hover here in indefinite darkness in infinite dangers. Thus reason shows the happy Polycrates the abyss of his misfortune; that's how Toggenburg's heart bleeds! "

Without giving an exact reason, the musician Johann Rudolph Zumsteeg praised various ballads of Schiller on November 24, 1797 . His later setting (see below), along with Schubert's, will be the best-known by the Knight Toggenburg : I also particularly liked: Toggenburg, Die Todtenklage , Die Kraniche und die Schöne Ballade, Der Gang nach dem Eisenhammer (ibid., P. 177).

Of your two other romances , the Knight Toggenburg is my favorite. Description and tone are characteristic and thus create an effect , said Wilhelm von Humboldt from Paris in December (ibid., P. 195).

Later reception and allusions

In his farce Das Mädel aus der Vorstadt Johann Nestroy alluded to the popularity of the ballad : he became a second knight, Toggenburg; that was the great love mathematician, who raised the window to the highest potency , he also always looked over and looked, and so he sat, a corpse, there one morning - you will have heard about the G ' layer ' .

In an autobiographical text Wilhelm Hauff confessed : I often feel like the knight Toggenburg .. It is true that it is not a nunnery that I set up my household across from; but maybe I don't look at the beautiful two-story house with less devotion and listen until a window sounds and I also hear words, because that's how I can only see people speak. I also gradually remain a bachelor like the melancholy knight, but God should keep me from giving up a little ghost like the Toggenburger .

Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué published a story in the Frauenzimmer-Almanach ... for the year 1817 under the title Knight Toggenburg , which takes place during the wars of liberation against Napoleon I (also printed in his: Blumenstrauss , Reutlingen 1818). When the protagonist heard Adelbrecht recite the ballad , it seemed to him as if the syllable before the syllable sounded with just as many solemn bells ringing at the grave, the decisive fateful saying in his life .

The Goethe and Schiller Archive Weimar announced that “that Karl Immermann has a contemporary copy of a comedy under the title 'Der neue Toggenburg. Comedy in an act by Michael Beer 1830 'is available (GSA 49/83 Bl 84-94). This copy is enclosed with the letter from Michael Beer to Karl Immermann of March 15, 1830 ”(Mail of December 12, 2005).

In his childhood memories, Paul Heyse reports that he once mentioned a pedantic poem in the presence of Karl Simrock that addressed the prehistory of Toggenburg. Suddenly Simrock stands still, turns around and says in the calmest tone: I was the pedant. It is Simrock's ballad Itha von Toggenburg (in the Rheinsagen , Bonn 1841 and more often).

In the Venus in Furs by Leopold von Sacher-Masoch (1870) it says: I am in love with someone else, and indeed most unhappily in love, even more unhappy than Knight Toggenburg and the Chevalier in Manon l'Escault . Similar to Karl Gutzkow : his mother pulled a face and almost contemptuously called the young painter the Knight Toggenburg from the studio.

In Fontanes Stine , Toggenburg appears in the same breath as Schiller's ballads that are better known today: it doesn't matter whether she declaims the Knight Toggenburg or the walk to the iron hammer or just the glove .

Karl May took up the ballad several times , including in Winnetou I (see below and Olbrich 2004).

The corpus database of the Digital Dictionary of the German Language of the 20th Century contains the following evidence on the proverbial use of the Toggenburg knight (found by searching for Toggenburg):

- v. Meysenbug, Malwida , "The Abbess's Path", in: dies., St. Michael , Berlin: Schuster & Loeffler 1907

- Ernst, Otto , Appelschnut , Leipzig: Staackmann 1907

- v. Bismarck, Hedwig, memories from the life of a 95-year-old, Halle: Richard Mühlmann (Max Grosse), 1913 [1910]: Once he said that he was the Toggenburg who looked at the window of his love

- Hauptmann, Gerhart , The Fool in Christo Emanuel Quint , Berlin: Fischer 1910

- Rafaeli, Max / Le Mang, Erwin, The Secret Love Powers , Dresden: Rudolph 1927, pp. 15–200

The finding that there is no evidence of such a common comparison from the second half of the 20th century is confirmed by a look at wortschatz.uni-leipzig.de.

When Robert Gernhardt quoted Toggenburg in his Düsseldorf acceptance speech for the Heinrich Heine Prize 2004, it is more likely a rediscovery and ironization of the text by a well-read author.

Allusions in scientific prose

The Toggenburg was also often alluded to in scientific prose. A reference can be found in Sigmund Freud (in his work Dora ) or in the introduction by Georg Lasson to Hegel's Encyclopedia : Philosophy is a bride who wants to be conquered. Anyone who does not find the courage to do so and yet woos her will always sit across from her as a Toggenburg knight who is no different from a corpse during his lifetime (quoted from Kant studies 1931, p. 284).

Karl Popper referred to Toggenburg's patience in a letter to Fritz Hellin dated July 20, 1943.

In Konrad Lorenz's essay "The Kumpan in the Bird's Environment" reference is made to the "Knight-Toggenburg behavior".

In Else Wildhagen's novel "Trotshead's Bridal Time", a comment is made about the self-sacrificing mourning of the knight Toggenburg.

Interpretations

For Heinrich Döring's Schiller biography from 1824, Schiller reached the highest peak in Toggenburg as a lyric poet . In the poem, unmistakably the spirit of the real ballad blows. What appeals to us so much in it is probably the simple and yet so touching material, which had to be gained twice by the simplicity of the treatment, by the deliberate avoidance of shiny images. Even through the brevity of the meter, Schiller gave the whole thing something peculiar and significant.

Karl Hoffmeister interprets the Toggenburg in more detail than Döring in Schiller's Life 1846: “He seems to have been tired of his previous plastic and grandiose ballad style, or for a change he set up a new genre. Here he first takes the longing for love into such a poem, and there is no basic idea, only a basic feeling. The earlier ballads are more preoccupied with the idea that this romance speaks to the heart. Not only the characters, but also the incident is very little motivated; some can only be guessed at. But the virgin turned away from an earthly inclination is better performed than the knight, whose vehemence and heroism one does not understand how these qualities could freeze into a motionless sensibility. But is it not peculiar to the elegy at all that it alone brings out the lonely, self-contained sensation and only draws everything else faintly and fleetingly? But our romance has such an elegiac tone as the previous one has a tragic one; and if these latter are to be compared with dramas, or if they are at least dramatically closed, this piece ends, as it were, in an idyll through the hermit's still life. Since there is no sublime idea and no struggle between man and nature and fate, not even an action, but a state of mind, there can be no talk of conciseness, energy and splendor of the presentation. In simple and natural language, the poet has laid down the sentimental feeling of a love that is pure, true and touching, which, although spurned, remains true to itself until death. "

School reading

Today the Toggenburg is no longer part of the classic canon of Schiller's ballads. Probably, however, most of the pupils - at least those of high schools - got to know the poem in the first decades of the 20th century. A document from Lily Braun's memoirs of a socialist who remembers school essays about Goethe and Schiller relates to the period around 1878 : B. loved Schiller above all else, I praised Goethe; so it says in an essay about the ballads of the two poets: 'Goethe is a poet of nature, that is, a poet by God's grace. The main thing for him is that the work he creates will be a work of art . Schiller, on the other hand, is of a different kind, because for him the work is only a means of moral preaching, '- here stands an' Oh !! ' the teacher next to him - 'you can see that in all his ballads, which are based on all possible doctrines: The walk to the iron hammer teaches that God protects innocence; the fight with the dragon, that victory over oneself is greater than that over the monster; the guarantee and knight Toggenburg show the value of loyalty, and the bell is almost entirely a didactic poem . "

Reception in music

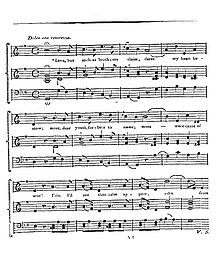

The ballad with the beginning of the text Knight! faithful sisterly love was repeatedly set to music. They have been musically arranged by composers from Schiller's own time (information from the national edition and Georg Günther, Schiller settings, Vol. 1–2, Marbach 2001):

- Johann Rudolph Zumsteeg (1760–1802), Schiller's school friend, active at the Württemberg court (see letter of February 12, 1800 to Schiller)

- Ambros Rieder (1771–1855), Austrian violinist, violist, organist and composer

- Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752–1814), printed in Leipzig 1810

Zumsteeg and Schubert

HA Köstlin wrote about Zumsteeg's version, which was also printed in London in 1800, in 1886: In families, where on Sunday afternoons or evenings one reaches with reverence for the old, delicately written music books from which our grandfathers and grandmothers play the piano Having sung or played, one may still hear the once so popular "Knight Toggenburg". Even though we young lads were malicious enough to smile at the tears that stole from the eyes of our busy knitting aunt when the piano sounded: "Knight, faithful sisterly love dedicate this heart to you", our hearts opened up the sounds of this undemanding, cozy music, and now, when this way happens to strike us, it looks at us like a dear greeting from an old, beautiful time, like a greeting from childhood.

Of Zumsteeg's four small ballads, the knight Toggenburg, whose composition is characterized by the alternation of song form, arioso and recitative, is the best known, says the article Zumsteeg (family) in: Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (vol. 14, p. 1432, cited: MGG).

Franz Schubert later also adopted the ballad (D. 397). His autograph of the song is from March 13, 1816, the first printing took place in 1832 in the estate (The Schubert Song Companion, 1997, p. 366). Schubert leaned very closely on Zumsteeg.

In Schubert's setting, the path from the external drama (farewell, cruise) to the internal silence (hermitage) is traced, from stanza to stanza everything becomes more rigid; The key of A flat minor remains frozen for long bars, whereby the composer captures the timeless persistence of the knight, who 'sits out' his love until death, in a musical image ( Veronika Beci : Franz Schubert. I moved in as a stranger . Düsseldorf 2003, p. 36).

Further settings

The following names are mentioned to prove the effectiveness of the original, not because they are outstanding works of musical art.

Bernhard Joseph Klein (1793-1832) posthumously published the Knight Toggenburg (Wenzel 1859 and MGG in the article Klein) among the posthumous ballads and chants in the second issue at Hoffmeister in Leipzig .

Carl Haslinger (1816–1868) arranged the "melodrama" for piano accompaniment.

Martin Plüddemann (1854–1897) also offered a musical version in his Ballads and Gesänge Vol. 4 (1893) (Günther II, p. 120).

According to Wenzel 1859, the ballads (Vienna: Mechetti and Comp.) By Johann Vesque von Püttlingen (1803-1889) contained the Knight Toggenburg as booklet 7.

In his autobiography Richard Wagner mentions a composer Weißheimer who had finished a symphonic poem The Knight Toggenburg . It was about his friend Wendelin Weißheimer (1838–1910), who found the program of the »New German School« in his symphony for large orchestra , which premiered on November 1, 1862 in the Leipzig Gewandhaus (so MGG vol. 14).

In Austria [1879] Franz Mögele (1834–1907) composed Ritter Toggenburg. Operetta in 2 acts by Moriz Schadek . First performance in Vienna on March 3, 1879 with Emil Jakob Schindler & Anna von Bergen in the title roles - the parents of Alma Mahler . ["Fremdblatt", Vienna February 28, 1879].

Translations and foreign language reception

In the 19th century in particular, the ballad was translated into a number of other European languages, especially English .

English translations

The Toggenburg was extremely popular in the English-speaking world. The order of the ballads in the essays by Thomas Carlyle (Boston edition 1860) is remarkable : The Ritter Toggenburg, the Dragon-fight, the Diver, are all well known (as already Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country 1831, p. 149).

In July 1867, Chambers's Journal of Popular Literature, Science and Arts (London and Edinburgh) read : he looked as Teutonic as Karl the Great or Ritter Toggenburg ( Lord Ulswater , p. 457).

To make it easier to identify the versions determined in the full text, the first two lines are given. The following list is far from exhaustive.

Thomas Hardy transmitted only the first stanza :

- Knight, a true sister-love

- This heart retains;

The (earliest?) Translation included in the 1800 London Zumsteeg print ( done into English by the translator of The German Erato ) was ascribed to James and Benjamin Beresford.

- "Love, but such as brothers claim, clares my heart bestow

Mr. Bowring is named as the author of the translation published in The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal (American Edition Boston: January 1821. Vol. 1, Iss. 1, p. 121) in 1821:

- Oh knight! a sister's love for thee

- My bosom has confess'd;

The original edition of the New Monthly appeared in London. Based on the name abbreviation J. results as the author of the British politician and author John Bowring .

The same text appeared anonymously in March of the same year, 1821, in The New - York Literary Journal, and Belles - Lettres Repository (Vol. 4, Iss. 5, p. 344). Likewise in The Atheneum, or, Spirit of the English Magazines (May 1, 1821; Vol. 9, Iss. 3, p. 106). With Responsibility, Mr. Bowring in: The Ladies' Literary Cabinet, Being a Repository of Miscellaneous Literary Productions, both Original and Selected in Prose and Verse (New York: July 14, 1821. Vol. 4, Iss. 10, p. 79) .

As early as October 1, 1824, The Atlantic Magazine (p. 470) noted that the bell, Knight Toggenburg, Fridolin (Der Gang nach dem Eisenhammer) and the Ring of Polykrates had been translated ably and variously (skilfully and differently).

When an author in the Cincinnati Literary Gazette (Vol. 2, Iss. 21, p. 166) wanted to introduce Schiller to an American audience on November 20, 1824 , he only highlighted Toggenburg among the less well-known ballads compared to the dramas emerged. Schiller strived for simplicity of feeling, narrative and diction. In this respect the Toggenburg had no parallel ( In the ballad he aimed at the utmost simplicity of feeling, and narrative, and diction. It would scarcely be too much to say, that, in this style, his "Knight Toggenburg" has no equal ; in German it certainly has none ).

A HBH was responsible for a transmission in Blackwood 's Edinburgh Magazine in 1829.

- LOVE, Sir Knight, of truest sister,

- From this heart receive;

An H. submitted in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction , No. 487 of April 30, 1831:

- "Knight, a sister's truest love,

- This mine heart devotes to thee--

Sarah Aikin published her translation in New York as Mrs. James Hall in her book Phantasia, and other poems .

- KNIGHT! true-sister love for ever

- Plights my heart to thee

It had already appeared in April 1842 in the journal Northern Light published in Albany .

In George MacDonald's (1824–1905) Rampolli the:

- True love, knight, as to a brother,

- Yield I you again; Ask me not for any other

The beginning of the translation by Constance Naden (1885–1889) reads:

- "KNIGHT, with sister's love for brother,

- Dear to me thou art:

The version in Project Gutenberg does not indicate the source :

- "I can love thee well, believe me,

- As a sister true;

In 1835, The Collected Poems of James Clarence Mangan performed a version of The knight of Toggenburg .

Edward Bulwer-Lytton's translation, according to Wurzbach von Tannenberg, can be found in The Poems and Ballads of Schiller (Leipzig 1844, p. 10).

In the English Schiller biography by HW Nevinson (1889, p. Xiii), a translation by WW (i.e., i. W. Whewell) printed in Shelford in 1842 is mentioned.

The Poetry of George Gissing (1857–1903) published in 1995 contains the Knight of Toggenburg (p. 125 ff.).

Probably only as a manuscript is The knight of Toggenburg (about 1849) of Medicine -Professors George Bacon Wood (1797-1879) before (in the College of Physicians of Philadelphia ).

Other languages

Wurzbach von Tannenberg listed translations into English, Italian, Swedish and Polish in 1859. For English he only mentioned Bulwer-Lytton 1844. Francesco Disconzi translated the ballad into Italian in the Rivista Viennese by DGB Bolza (Vienna 1839). A Swedish translation can be found in Karl August Nicander's (1799–1839) travel memories from the south (Minnen fran Södern, Örebro 1831, p. 121ff.). The ballad was freely transferred under the title Celina in the Polish collective work Polyhymnia (Lemberg 1827, vol. 6, p. 1), precisely by Kazimierz Brodziński in the Pienia Liryczne as Rycerz Toggenburg p. 36 (in the works / Dziela vol. 2, P. 33 under the title Alfred i Malwina ). In Hungarian it is contained in Count Franz Teleki v. Szék von Döbrentei poems (1834) and in Fr. Fidler's collection of Hungarian translations of Schiller's poems.

Daniel Amadeus Atterbom (1790–1855) began his translation into Swedish Riddar Toggenburg with Kuno, trogen syskonkärlek (Kuno, loyal sister love ) and thus gave the knight without a given name a knightly romantic first name.

Steingrímur Thorsteinsson (1831-1913) translated twelve of Schiller's poems into Icelandic , including Toggenburg ( JC Poestion , Isländische Dichter der Neuzeit, Leipzig 1897, p. 442).

On the website preseren.net you can listen to the sonnet Velika, Togenburg by the most important Slovenian poet France Prešeren (1800–1849), in which he addresses Toggenburg as a painter, comparing the fate of the lyrical self with that of Toggenburg, as MP3 in Slovenian .

Vasily Zhukovsky's (1783–1852) translation into Russian (first published in 1818) was praised by Belinsky as excellent. It was probably she who conveyed the Toggenburg material to Dostoyevsky , from which he was inspired in his story The Little Hero (1849) (according to PR Hart in: The Slavic and East European Journal 15/3, 1971, p. 305– 315). The figure Toggenburg also appears in Turgenev's Fathers and Sons (English edition Fathers and Sons, Oxford 1998, p. 92). In the "History of the Russian Ballad" by Friedrich Wilhelm Neumann (1937, pp. 131, 322) it is assumed that Schiller's Toggenburg could have been the model for Pushkin's ballads Legenda and Romans .

As early as 1813, the Ridder Toggenburg can be found in the Procne collection of the Danish poet Bernhard Severin Ingemann (1789–1862) .

In the Amsterdam Almanak voor het Schoone en Goede. Before 1838 Vinkeles published a ballad Toggenburgs Non .

In Mexico in 1869 José Sebastián Segura (1822–1889) translated the text as El Caballero de Toggenburgo (I, p. 226f. After Andreas Kurz, The emergence of modernist aesthetics and their implementation in prose in Mexico ) in the journal El Renacimiento [.. .], Amsterdam 2005, p. 49).

László Cholnoky (1879–1929) wrote a Hungarian prose piece, The Knight of Toggenburg .

Eques Toggenburg is the title of the Latin version of the philologist Johann Dominicus Fuss (1781–1860) in the Poemata latina published in 1837

For parodies in other languages see below.

Parodies in German

The Toggenburg has been parodied repeatedly . Even the synopsis in Karl May's The Path to Happiness takes on humorous traits from the material: “'Well, he loved a damsel too, and she didn't want him. So he went to the holy land and knocked the heads off the unbelievers. Then, when that too got boring for him, he came home again. Maybe he thought he could get the damsel after all. ' 'Didn't she want to now either?' ,No. She is already in the monastery and has become a nun just as you want to be one. And always towards the evening, when she opened her window and looked out a Wengerl. Because the knight noticed this, he rented a room opposite and sat down by the window. When she looked out, he also opened the windows. Then we looked at each other for a while until it got dark. '"

The most important parody in poetry comes from Christian Morgenstern . She begins:

- Knight, love in great measure,

- Ladies let it run cold.

Even Joachim Ringelnatz created with knights castle socks also a parody in the 1928th

An anonymous wrote The violence of schnapps about love , which the bibliographies of 1859 (Wurzbach von Tannberg / Wenzel) cite with several proofs of printing (supposedly first published in 1824). This information is obviously incorrect, a print in the Library of Frohsinn (Stuttgart: Franz Heinrich Köhler), Section V, Vol. 2, 1837, pp. 77-79 No. 11 (facsimile) could be determined. The end of the text is quoted:

- Until the liquor showed its strength

- Until the dear heart

- Leaned down under the table,

- Falling without pain;

- And so he lay, a corpse

- There one morning

- After the shot glass, the pale one

- Silent countenance saw.

Based on the Jewish-German language , Anonymus Itzig Feitel Stern wrote under the original title: Poet Itzig Feitel Stern nouch Ritter Toggenborrig, who made Schiller an anti-Jewish parody. It appeared for the first time in the volume Gedicht vun dien grauße Lamden der Jüdischkeit self-published, Munich 1827. Under the same book title, the FW Goedsche-Verlag in Meissen published these early writings again in 1830, to which extended second and third editions (1831 and 1832) now under the title Poets, Perobeln and Schnoukes followed. The Goedsche-Verlag finally published a version of the parody that was partially changed and with an even sharper anti-Jewish accent in the publisher's fourth edition of the poems, Perobeln unn Schnoukes fer unnere Leut , at the same time 1st part of Itzig Feitel Stern's writings . Wurzbach von Tannenberg (No. 449) referred to the latter edition, in which the parody was printed under the title: Der Jüden Taggenborig ouder der Dichter Itzig (Kimpenirt nouch Ritter Toggenborrig, dien Schiller had made, ze beat ouf de Gitahr, ze paint on the vigeline, sing on the piano) . According to the latest research, both Heinrich Holzschuher and the Franconian baron and district judge Johann Friedrich Sigmund von Holzschuher (1796–1861) hid behind the pseudonym Itzig Feitel Stern .

The Lyrik.ch website on the Internet can be found on the Lyrik.ch website Des Ritters Stachelburg's Eternally Lost Love by the Bolzano- based author Donat von Sempach (born 1970), a satirical examination of Schiller's original.

Parodies in other languages

The most popular English-language parody is found in the hugely popular ballads by Bon Gaultier (actually William Edmondstoune Aytoun and Theodore Martin), which saw many editions: Bursch Groggenburg (after the edition of the Book of Ballads London 1849).

The Dutch poet JME Dercksen (1825–1884) also created a parody with his Klaas Tobbenburg .

In 1854 Kosma Prutkow ( pseudonym of several Russian authors) parodied the ballad, which was translated into Russian by Zukovskij, as follows (translation):

German ballad

- Baron von Grienwaldus,

- The pride of Germania,

- In Söllern and armor

- Sitting on a stone

- Before the castle of Amalia;

- Sits, the forehead is afraid,

- Sit there and be silent.

- Amalie refused

- The hand of the baron! ..

- Baron von Grienwaldus

- Turns from the window

- Not the eyes of the castle

- Don't move from the spot

- Drink and eat - nothing.

- The years go by ...

- Barons: they fight

- Barons: they feast;

- Baron von Grienwaldus,

- The brave knight

- Squats in the same place

- On the same stone.

photos

When Bernhard Neher (the younger) created illustrations for various works by Schiller in the Princely Residence Palace in Weimar around 1836/40 , he also chose the Toggenburg knight as one of the themes for his murals (description by Adolf Schöll 1857, p. 336 ff.).

A drawing based on the ballad is in the Kupferstichkabinett of the Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe . “It comes from August von Bayer, was created around 1850/55 and has the shape of a triptych . Shown are the knight's farewell to the lady who rejects his love (left wing), the nun's life of the lady (right wing) and the dying knight with the hermitage, the Toggenburg and the monastery opposite (middle picture). The drawing is the draft for a painting commissioned by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia, the location of which is not known to us ”(Kindly communicated by the museum, cf. in detail Die Deutsche Drawings des 19. Jahrhundert. Karlsruhe 1978, volume p. 39 No. 141). August von Bayer (1803-1828) tried in the summer of 1852 to win the Thurgau historian Johann Adam Pupikofer to add a story of the Counts of Toggenburg to the work. The impression created by Bayer that the royal client wanted this, however, was incorrect, as a query in Berlin revealed. Pupikofer's elaboration, which occupied him until 1861, remained a manuscript . In December 1855 Bayer exhibited the painting, an imitation of a Gothic winged altar and testimony to the painter's romantic sentiments, in Karlsruhe. The following spring he gave it to the king. There must have been another version signed by Bayer from 1864, which - according to Arthur von Schneider (Baden Painting of the 19th Century, 1968, p. 62) - appeared in the US art trade after the Second World War.

Even Heinrich Jakob Fried and Carl Alexander Heideloff created images for the ballad. Fried's picture is apparently lost. Heideloff's oil painting from 1811 for Count Fries in Vienna mentions an autobiographical record. Thieme-Becker added from an unknown source: lithogr. v. Wieser .

Around 1875 Carl Spitzweg painted the Knight Toggenburg (Georg Schäfer Museum in Schweinfurt).

There were also illustrations for ballads, e.g. B. Outlines for Schiller's Toggenburg designed by Gustav Dittenberger (1794–1879), 1825 (9 copper engravings, at Cotta ).

The historical-genealogical calendar for the year 1811 contained pictures of six Schiller's ballads by FW Bollinger (based on drawings by L. Wolf), including the Toggenburg .

In Cotta's magnificent edition of Schiller's poems from 1859, the illustration is by Arthur von Ramberg .

In addition to Dittenberger's work, the art collection of the German Literature Archive in Marbach holds a depiction of the sleeping or dead hermit painted by Philipp von Foltz (1805–1877) and lithographed by Gottlieb Bodmer (1804–1837) (inv. No. III 361). In 1821, Johann Heinrich Ramberg (1763–1840) and the engraver Johann Friedrich Rossmässler jun. (1775–1858) in Dresden an etching (inv. No. 1363/7), which also appeared in Penelope - paperback for the year 1823 . In the illustrations for all of Schiller's works (inv. No. 856–859), Stuttgart: Xylographische Anstalt 1838/39, Toggenburg appears in issue 5/6. It is also represented in a steel engraving on Schiller's sites on Plate XXXVI, dedicated to the Schiller House in Lauchstädt (Inv.-No. 3646). (The above information after a friendly communication from Marbach.) In an antiquarian offer , the last-mentioned piece is described as follows: Bad Lauchstädt. Souvenir sheet. Scenes from Schiller's works are grouped around the central picture with a view of the Schiller House: Fridolin, Knight Toggenburg and Battle with the Dragon. Toned wood engraving by Cohn after V. Katzler around 1860.

The Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest keeps caricatures for Schiller's "Knight Toggenburg" (16 sheets, around 1865) by the Hungarian draftsman Albert Almássy (Almásy).

Schadow asked me , remembers the late romantic Caspar Scheuren in his autobiography for the year 1830, to diligently compose the evening and try my hand at the historical, whereby he also set me the task, like "Götz von Berlichingen wounded among the gypsies". This "Toggenbruck" and "Kain's manslaughter" of mine seemed to appeal little to him, and so I followed my nature all the more, namely to try and invent landscapes. (Ed. by Wolfgang Vomm in: Wallraf-Richartz-Jahrbuch 65, 2004, pp. 249–72, here p. 259). A watercolor from 1835 with the title "Knight Toggenburg" was formerly in the palace library in Berlin .

During his childhood in Stavenhagen , the later Low German writer Fritz Reuter, who was born in 1810, enjoyed himself with a popular sheet of pictures about the Toggenburg knight: There was a real knight sitting there, and what a knight! And yet his limbs were not wrapped in armor of ore and iron, which I had previously thought to be as inseparable from the knights as the shell from the crabs. He was tall and strong, but he wore a kind of dressing gown, tied with a belt, and looked over at an open window, at which a modest face was shown, which looked out curiously, as I had often noticed with Friederike Wienken, our room maid when she swept the rooms on the second floor and looked searchingly down the street. I colored this picture sheet very well and had the luck or bad luck, as you like, to depict the Toggenburger's face in a very bright red.

Sources and material relationship

Schiller's works (national edition): 2nd volume. Part II A (1991): Writing poems (notes on volume 1): The question of a direct source for the material of the ballad is open. Based on the name Toggenburg (the former county has belonged [since 1803] to the canton of St. Gallen), reference should be made to the legend of Ida (Idda) von Toggenburg (told since the 15th century); she was suspected of unfaithfulness and cast out by her husband, Count Heinrich von Toggenburg; then she retired as a hermit in the area of Fischingen Abbey in Thurgau , where she is said to have died around 1184; Heinrich, who asked her to return in vain after she was innocent, also went to the hermitage out of repentance. Schiller could have become aware of the material through the novel "Elisabeth, Erbin von Toggenburg" (1789) by Christiane Benedigte Eugenie Naubert (1756-1819); see. Köster, The knight and robber novels (1897). It is possible that suggestions came from Johannes von Müller's "Stories of Swiss Confederation", which Schiller had known for a long time (cf. to Crusius of November 5, 1787), in which the legend is told (1 [1786], 380) (p. 607 ).

The Swiss scene is given by verse 14, which (anachronistically) speaks of the country of Switzerland. The Toggenburg (today Alt-Toggenburg) is called the family's ancestral castle . Whether the Ida legend actually inspired the poet seems doubtful. The legends do not know that Heinrich also went to a hermitage. The "national edition" refers to the review by Albert Köster: The knight and robber novels. a contribution to the educational history of the german people by Carl Müller-Fraureuth. Halle [...] 1894. In: Anzeiger für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Litteratur 23 (1896/97), pp. 294–301, p. 299f. underlined the possible influence of Naubert's novels on Schiller. The intricacies of Naubert's novel would have inspired Schiller.

It is closer to the assumption that Schiller transferred the name Toggenburg, which seemed impressive to him, to something else known to him or to motifs he put together.

The motive that a knight took part in a crusade and found his mistress as a nun on her return was in the air in the literature of the late 18th century. Hermits and hermits from lovesickness were also well known in chivalric novels. While homecoming stories - see the narrative type Homecoming of the husband , which is widespread in folklore and world literature - give the story a happy turn (the lover / husband just manages to prevent the wedding), Schiller lets his hero arrive one day late.

Hoffmeister 1846 (see above) gave the following reference to a source: According to Götzinger, Schiller had a Tyrolean legend (as is well known, a similar one plays on the Rhine, on Nonnenwörth and Rolandseck) in mind (Götzinger means Max Wilhelm G., German poet T. 1 , 1831, p. 202). Götzinger could no longer remember whether he had read or heard the legend. Subsequently, the tradition of the Wolkenwiegt monastery by Karl Goedeke (Schiller, Complete Writings 1: Gedichte, Stuttgart 1871, p. 449f.) Could be traced back to the Knüttelgedichte by Georg Wilhelm Otto von Ries (Altona 1822, pp. 145-163). Since there is no such monastery (the localization Tyrol was made due to the castle name Wolkenstein) and the - aesthetically unsatisfactory - poem was apparently turned according to the model of the Toggenburger, on which He, Tokkenburger! is explicitly alluded to, it is a question of a Schiller reception and not a source.

In 1997, Klaus Graf was able to determine the legend of Roland and Hildegunde located at Rolandseck Castle : It is considered a literary creation based on Schiller's ballad "Ritter Toggenburg" from 1797. Now, however, the Koblenz priest Joseph Gregor Lang referred to the material core in 1790 the story, which is expressly referred to as "old legend": Rolandseck Castle was only built by Roland, Charlemagne's nephew, to be close to his beauties, who lived imprisoned in Nonnenwerth Monastery.

For example, in 1831 Johanna Schopenhauer wrote : Only separated from the island by a narrow arm of the Rhine, the beautiful Rolandseck rock with the ruins of his ancient castle rises on the left bank above the road below it, but they are by no means as picturesque as the travel writers say so. The only two pillars still standing, with the crossbeam resting on them, look from below more like a dilapidated, somewhat colossal gallows than the remains of an old knight's castle, which incidentally, if the legend does not lie, is written from a distant past. Roland, nephew of Emperor Charlemagne, is said to be its builder, whose love for a consecrated virgin, albeit under a different name for unknown reasons, brought Schiller to posterity in the ballad: "Knight Toggenburg"; Here, in front of his specially built Rolandseck Castle, hundreds of years ago stood the loyal knight and looked longingly down at Nonnenwerth, right below him, "until the window sounded," so the tradition prevailing among the people asserts.

August Kopisch dedicated a short poem to the Rolandseck material.

Gottlieb Konrad Pfeffel (1736–1809) tells a similar story to Charibert and Adelgunde in his prose essays vol. 3, Tübingen 1811. The text mentions the year 1793 (p. 178), so it was written between 1793 and 1809.

Individual evidence

- ↑ cf. Friedrich Schiller (Ed .: Musenalmanach for the year 1798, Cottasche Buchhandlung, Tübingen, 1797) in the Friedrich Schiller Archive

- ↑ Online , the quote and date from Schiller's works (national edition): 37th volume. Part II, 1988.

- ↑ nestroy.at

- ↑ fh-augsburg.de

- ↑ p. 202 in the PDF

- ^ Paul Heyse : Memories of youth and confessions in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ Text on gutenberg.spiegel.de ( Memento from January 26, 2005 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Karl Gutzkow : The knights of the spirit in the project Gutenberg-DE

- ^ Theodor Fontane : Stine in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ^ Otto Ernst : Appelschnut in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ duesseldorf.de

- ↑ unav.es

- ↑ Konrad Lorenz: The friend in the environment of the bird . In: About animal and human behavior. From the development of behavioral research. Collected Treatises. Vol I. Piper, Munich 1965, p. 115–282 , allusion to Toggenburg on p. 227 ( klha.at [PDF; 1,1 MB ; accessed on January 14, 2019] Provided by Konrad Lorenz Haus Altenberg (KLHA) ). First published in Konrad Lorenz: The friend in the bird's environment . In: Journal of Ornithology . tape 83 , 1935, pp. 137-213, 289-413 .

- ↑ kuehnle-online.de

- ↑ Wissen-im-netz.info ( Memento of the original from November 25, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ gutenberg.org

- ↑ jadu.de ( Memento of the original from June 11, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Print from 1900

- ↑ ibiblio.org ( Memento from November 25, 2002 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ hti.umich.edu ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ POEMS OF THE PAST AND THE PRESENT by Thomas Hardy

- ↑ facsimile

- ↑ books.google.com

- ↑ gutenberg.org

- ↑ gutenberg.org

- ↑ indiana.edu

- ↑ gutenberg.org

- ↑ collphyphil.org ( Memento of the original from October 4, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ visarkiv.se ( Memento from January 17, 2003 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ preseren.net ( Memento from March 29, 2001 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ adl.dk ( Memento of the original from March 2, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ dbnl.org

- ↑ mek.oszk.hu

- ↑ karl-may-gesellschaft.de

- ^ Alfred Klepsch: Jewish dialect poetry by non-Jews in Franconia. Das Rätsel des Itzig Feitel Stern, in: Yearbook for Franconian State Research, published by the Central Institute for Regional Research at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Volume 68 (2008), p. 169 to p. 201

- ↑ lyrik.ch

- ↑ dbnl.org

- ↑ home.arcor.de

- ↑ Adolf Schöll: Weimar's oddities once and now a guide for foreigners and locals: Including a statistical-topographical appendix, together with an address directory of the authorities and the most important private institutions, a messenger, post and railway reports . Landes, 1857 ( digitized page 337 ).

- ↑ H.-U. Wepfer: Thurgauian contributions. 106, 1969, pp. 100-103.

- ↑ Ed. By Urs Boeck 1958, p. 386 . See also Andrea Knop: Carl Alexander Heideloff and his romantic literature program . Nuremberg 2009, p. 32.

- ^ Fritz Reuter : Schurr Murr in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ^ Two contemporary reviews of Naubert's novel

- ↑ histsem.uni-freiburg.de ( Memento from January 10, 2004 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Johanna Schopenhauer : Excursion to the Lower Rhine and Belgium in 1828 in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ Facsimile in a later collection of Rhine sagas

- ↑ Gottlieb Konrad Pfeffel : Charibert and Adelgunde . In: Prose Attempts Vol. 3 . Tübingen 1811, urn : nbn: de: bsz: 25-digilib-61198 ( uni-freiburg.de ).

literature

- Wendelin Weißheimer: Experiences with Richard Wagner, Franz Liszt and many other contemporaries . Stuttgart and Leipzig 1898.

- Constant Wurzbach von Tannenberg: The Schiller book . Vienna 1859, p. 28

- Carl Gustav Wenzel: From Weimar's golden days . Dresden 1859, pp. 300-301

- Arthur von Schneider: An unknown work by August von Bayer , in: Writings of the Association for the History of Lake Constance and its Surroundings , 63rd year 1936, pp. 115–122 ( digitized version )

- Willi Olbrich: From Friedrich Schiller to Karl May . In: Mitteilungen der Karl-May-Gesellschaft 36 (2004), No. 139, pp. 24–26 online

Web links

- (1.38 MB, OGG)

- Knight Toggenburg in the Gutenberg-DE project