Phaistos Disc

The Phaistos Disk ( Greek Δίσκος της Φαιστού , also Phaestus Disk or Festos Disk ), a burnt clay disk found in Phaistos on Crete , is one of the most important finds from the Bronze Age . It is provided with abstracts, human, animal and material motifs (tools and plant parts) arranged in circles and spirals, which were impressed with individual stamps. The disc represents the first known " print with movable letters " of mankind, in the sense that for the first time a complete body of text was produced with reusable characters.

The Phaistos Disc is unique as no other find of its kind has been discovered so far. Almost all questions relating to the disc, such as its purpose, its cultural and geographical origin, the reading direction and the front, are controversial. Even its authenticity and the assumption that the characters are written characters have already been questioned. The unique object is now in the Archaeological Museum in Heraklion .

Discovery, location and dating

Location

Coordinates of the place of discovery: 35 ° 03 ′ 06.0 ″ N, 24 ° 48 ′ 53.5 ″ E

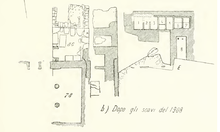

The disc was found on the evening of July 3, 1908 during excavations by the Italian Luigi Pernier in the course of the Italian Archaeological Mission of 1908 led by Federico Halbherr 1857–1930. He was discovered in the westernmost building of the ancient palace- era northeast wing of the Minoan palace complex of Phaistos on Crete . However, Pernier was not personally present when it was found. The disc was about half a meter above the rock, inclined to the north with the side later called "A" facing up between rubble and ceramic remnants in a rectangular 1.15 × 3.40 meter store room, which is now Chamber 8 of the building 101 is designated. Next to him was a broken tablet (Ph-1) in linear script A , ceramic from the period 1650 to 1600 BC. Chr., Ashes, coal and burned cattle bones. The room had no level access. To the north of the chamber 8 there is a series of containers separated by bricks, which extend to the west over the west wall of the chamber. Pernier did not provide any stratigraphic information on the exact position of the disc in chamber 8. This limits the possibilities for the relative dating of the disc from the context of its find.

Dating

Luigi Pernier dated the creation of the disc between 1700 and 1600 BC. BC, to the period Middle Minoan III . He assumed that the disc was not kept in the room where it was found, but that it fell into chamber 8 from an upper floor when building 101 collapsed. Pernier already pointed out, however, that although the majority of the ceramic finds in the discovery room of the disc came from the Middle Minoan period, some Hellenistic finds did not match them. The stratigraphic data of the place of discovery cannot be used for the temporal classification of the disc because it is ambiguous, especially since the time of its production does not have to coincide with the time of storage at the place of discovery. Scientists like Yves Duhoux and Derk Ohlenroth are therefore expanding the possible production period of the disc to include Middle Minoan II, and thus a total of 1850 to 1550 BC. BC, and refer to the use of building 101 already in the old palace period .

If one ignores extreme positions, such as the one that the Phaistos disc is a forgery or the scientifically unsubstantiated hypotheses of its origin by Victor J. Kean (2100 BC) and Kristian Jeppesen (1924-2014-1100 BC), In addition to the classic dating according to Pernier and the extended Middle Minoan according to Duhoux and Ohlenroth, there are scientists who assume the emergence of the disc in the late Minoan period. They include Benjamin Schwartz , Henry D. Ephron, and Louis Godart . After examining the signs on the clay disc and their temporal reference to the archaeological reality of Crete, the latter comes to the conclusion that the disc “chronologically dates back to 1550 BC. And the end of the 13th century BC Is classified ". In contrast, Günter Neumann (1920–2005) and Kjell Aartun pointed out that certain signs on the disc correspond to those on the bronze ax of Arkalochori found in the 1930s and with three male clay statuettes from the summit shrine of Traostalos discovered in the early 1960s . Both the bronze ax, the characters of which were associated with Linear A and interpreted as syllabary, and the use of the cave sanctuary are generally dated to the Middle Minoan Period I to III, with the ax dating from 1700 to 1600 BC. Chr.

Problem of possible forgery

The art dealer Jerome M. Eisenberg, who specializes in ancient artifacts, suspects Luigi Pernier, the Swiss artist and restorer Emile Gilliéron , (1851-1924), who worked with Arthur Evans on the excavation of the Knossos palace , to have forged the disc . The results of the work of Emile Gilliéron and his son Emile (1885–1939) are often "artistically very free" or are viewed by some specialists as pure art forgeries. Their work was not based on the archaeological standard at that time either; some things (like the Phaistos disc or the snake goddess of Knossos) are even suspected of being pure fakes . Thermoluminescence examinations could not be carried out on the art object.

After an analysis of Eisenberg's results, the ancient orientalist Pavol Hnila came to the conclusion that the discussion about the authenticity of the disc was not yet over. Sign no.21 on the disk (see right) in particular testifies that the forgers should have had an almost unexplainable knowledge of the conceivable or possible repertoire of signs, since the exact same sign almost half a century later from a secure find context on a Minoan seal imprint in Phaistos was found. No other copies have become known. In contrast to Eisenberg's assessment that none of the 45 characters could be inserted into any of the systems of other Minoan scriptures, Hnila emphasizes that, in addition to the seal imprint from Phaistos, comparable characters can be found on the ax from Arkalochori found in 1934 and on the "altar stone" from Malia . Some of these signs are very similar, if not identical.

description

Structure and structure

The clay disc of the disc is flat and irregularly round. Their diameter varies between 15.8 and 16.5 centimeters. The surfaces of both sides, which are distinguished by the designations A and B, are smooth, but not even and flat . The thickness of the disc varies between 1.6 and 2.1 centimeters, with side A thickening at the edge and side B in the middle. The disc consists of high-quality fine-grained clay, in the color spectrum from light golden yellow to dark brown, which was carefully burned after the stamping. The type of material is reminiscent of the Cretan eggshell ware .

Both sides of the disc are stamped with abstracts, human and animal signets as well as equipment and plant motifs, arranged in an outer circle and spiral inward. It is labeled with a total of 241 stamp impressions, which are grouped into 61 groups of characters by dividing lines (so-called field separators ). Side A contains 122 stamp impressions and 31 groups of characters. A gap on side A refers to a sign that was previously there, so that the total number of stamps when the disc was made was 123. On page B there are 119 impressions, summarized in 30 groups of characters. The longest groups of characters have seven stamps, the shortest two. On side B there are only group sizes with two to five characters and on side A with two to seven characters. The numbering of the character groups is indicated differently, for example Arthur Evans designated the character group with the rosette in the center as A 1, Louis Godart on the other hand as A-XXXI.

According to the numbering of Louis Godart, the following groups of characters are shown on both sides of the disc, A and B - the characters are mirrored in the table according to the reading direction assumed by Godart from outside to inside, i.e. from right to left. In the character group A-VIII (A8), the last character in the gap there is missing or can no longer be identified:

Corrigenda to the scientifically exact representation of the character strings in the above representation (apparent comparison with the original disc): The mirror-inverted representation is irritating, since all other representations of the character strings of the disc in the literature correspond to the original and not the stamps used, which were not found. Some of the drawings do not correspond to the original: (A1) “Thorn” under “Angle” is missing; (A3) "Dorn" under character (07) is missing; (A9) "Falcon" (31) Position incorrect, in the original it flies upwards and not horizontally; (A12) "Dove" (32) Position incorrect; is tilted backwards in the original. The “thorn” is missing under “rosette” (38). (A15) “Cattle foot” (28) Position incorrect, in the original points with the hoof up, not down. The “Dorn” is missing under “Runner” (01). (A16) The mandrel is missing under "Flame" (26). (A19) the same; (A21) “Cattle foot” (28) incorrect, in the original the hoof points upwards. The spike is missing on “runner” (01). (A22) "Falcon" (31) in the original flies with the prey upwards, ie on its back. The “thorn” is missing from “Flamme” (26). (A23) "Taube" (32) is tipped back in the original. (A25) "Falke" (31) flies up in the original, perpendicular to the line boundary. (A27) The thorn is missing on “Branch with five leaves”. (A29) The reduplication of "animal fur" (27) is in the original with the necks down, not up. On side B there are similar deviations from the original: "Spines" are missing, rotations of the "cat's head" (29) are not taken into account. "Ram's head" (30) points in the original with the snout up and not horizontally. As long as the disc has not been deciphered, a scientifically accurate representation could be important.

Signs, symbols and pictograms

The disc contains a total of 45 distinct stamp motifs, which can be identified as abstracts, people and animals, as well as objects (equipment, weapons, parts of plants). There are also 17 so-called mandrels, line markings under the first character of a department, counting from the center of the disc.

- Detailed views of the disc

Among other things, three animal skins, a man's head with a tufted helmet or mohawk , in the center a rosette

The various stamps of the disc have been numbered and have specific names that go back to the designations of Louis Godart. In addition, the signs were described by other scientists who gave them different meanings. The table below lists the most common descriptions and indicates how often a symbol appears on the disc and whether it is only on one of the two sides. As above, the characters are mirrored, so they would be identical to the stamp, not the imprint:

| № | character | UCS | Sign of the disc (UCS name, after Godart) | Descriptions | number | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | ? | PEDESTRIAN | Walking, almost marching man with a short apron |

11

|

||

| 02 | ? | HEAD WITH FEATHER DECORATION | Head of a man with a spring-loaded helmet (Pernier, Evans, Godart); with strange hairstyle (Davaras, Dettmer) |

19th

|

Always at the beginning of the word (if reading direction inwards) | |

| 03 | ? | HEAD WITH TATTOO | Bald male head with a figure in the form of an 8 on the cheek - a double earring (Dettmer); a tattoo (Pernier, Godart) |

2

|

On side A only | |

| 04 | ? | PRISONER | Naked man with forearms crossed behind his back - prisoner (Evans, Godart); striding farmer (Aartun); female prisoner (Dettmer) |

1

|

page A | |

| 05 | ? | CHILD | Naked male child with a bald head |

1

|

Side B | |

| 06 | ? | WOMAN | Woman in front and side views |

4th

|

||

| 07 | ? | HELMET | Bell-shaped symbol - cap (Pernier); Helmet (godart); female breast (Evans, Dettmer); Water tank (kean) |

18th

|

||

| 08 | ? | GLOVE | Bandaged hand or glove - combat glove (godart); Work gloves (Dettmer) |

5

|

||

| 09 | ? | TIARA | Special type of headgear - tiara (Evans); severed male genitalia? (Ohlenroth) |

2

|

On side B only | |

| 10 | ? | ARROW | Arrow (Godart, Dettmer); Ear of wheat (Ohlenroth) |

4th

|

On side B only | |

| 11 | ? | ARC | Horn bow with hanging tendon |

1

|

page A | |

| 12 | ? | SIGN | Circle with seven raised decorative points - round shield (Evans); possibly also offering table (Pernier); Discos (Dettmer) |

17th

|

15 times on side A. | |

| 13 | ? | CLUB | Club with knob-like bulges; Plant (Dettmer); Cypress (Ohlenroth); Grain Ear (Kean) |

6th

|

||

| 14th | ? | HANDCUFFS | Mountains (Pernier); Handcuff (Evans, Godart); Yoke / supporting timber (Dettmer, Ohlenroth); Footstool (aartun); Rock formation (kean) |

2

|

||

| 15th | ? | PICKAXE | Pickaxe |

1

|

Side B | |

| 16 | ? | SAW | Knife / saw with round blade and curved handle - knife (Ohlenroth); Animal skin (kean) |

2

|

On side B only | |

| 17th | ? | COVER | Upright lenticular object with an eyelet / handle in the middle - cutting tool for leather (Evans); Lid (Godart) |

1

|

page A | |

| 18th | ? | BOOMERANG | Carpenter's square (Evans); Boomerang (godart); Corner / angle (Aartun) |

12

|

||

| 19th | ? | PLANE | Joiner's planes (godart); Branch (aartun); Ruler with 60 and 120 degree legs (Dettmer) |

3

|

On side A only | |

| 20th | ? | DOLIUM (BARREL SNAIL) | Handle vase (Evans); Barrel snail (godart); bulbous vessel (Dettmer), measure of capacity (Aartun) |

2

|

On side B only | |

| 21st | ? | COMB | Comb (godart); Comb / rake (Ohlenroth); Web comb (Dettmer); Hoe / rake (aartun); Local Hieroglyph (Kean) |

2

|

On side A only | |

| 22nd | ? | SLINGSHOT | Double flute with long mouthpiece (Evans); Slingshot (godart); Radians (Dettmer); Whisk (aartun); Fork wood (Ohlenroth) |

5

|

On side B only | |

| 23 | ? | PILLAR | Column with capital (Pernier); Square head hammer (Evans); Club (aartun); Stamp (Dettmer) |

11

|

||

| 24 | ? | BEEHIVE | Pagoda-like building (Evans); House (Aartun, Dettmer); Beehive (Godart); Palankin, Lycian grave building (Ohlenroth); large structure (kean) |

6th

|

||

| 25th | ? | SHIP | Ship with an arrow protruding from the bow - ship (Evans, Godart); Saw bow (Aartun); Plow (Dettmer); grazing animal (kean) |

7th

|

||

| 26th | ? | HORN | Horn of an ox; Tail / tail (aartun) |

6th

|

||

| 27 | ? | ANIMAL SKIN | Animal hide / fur from a cow (Evans, Godart); of a goat (Dettmer) |

15th

|

||

| 28 | ? | BULL FOOT | Foot of a bull / ox; penis

(Paulus) - Fig. Is upside down! |

2

|

On side A only | |

| 29 | ? | CAT | Animal head in profile - cat's head (Evans, Godart, Ohlenroth); Bull biters (Pernier); Wild dog (Dettmer) |

11

|

||

| 30th | ? | ARIES | Head of a sheep with horns |

1

|

Side B | |

| 31 | ? | EAGLE | Flying Bird - Eagle (Evans, Godart, Dettmer); Falcon (Aartun, Ohlenroth) |

5

|

On side A only | |

| 32 | ? | DOVE | Sitting bird - dove (Evans, Godart, Ohlenroth); Duck (Dettmer); Goose (aartun) |

3

|

||

| 33 | ? | TUNA | Fish ( bluefin tuna ) |

6th

|

||

| 34 | ? | BEE | Insect - bee (Godart); Back view of a lying cow (Dettmer); Bunged wineskin (aartun) |

3

|

||

| 35 | ? | PLANE | Branch of a plane tree (Pernier); Plant or tree symbols (Evans); Oak (Dettmer); Fruit (aartun); Branch (Ohlenroth) |

11

|

||

| 36 | ? | WINE | Olive branch (Evans); Perennial (Ohlenroth); Weinstock (Godart, Dettmer); two-part black coral (aartun) |

4th

|

On side B only | |

| 37 | ? | PAPYRUS | Plant with flower and buds (Evans); Papyrus (Godart); blooming flax stem (Dettmer); Straw (aartun); Lily (Ohlenroth) |

4th

|

||

| 38 | ? | ROSETTE | Eight-petalled flower (aartun); Rosette (Godart, Ohlenroth); Lotus blossom (Dettmer) |

4th

|

||

| 39 | ? | LILY | Saffron (Pernier); Husk (aartun); Lily (godart); Crocus (Ohlenroth); Herbstzeitlose (Dettmer) |

4th

|

||

| 40 | ? | OX BACK | Indefinite / unrecognizable sign; Saddle of ox (Godart); Scrotum (Ohlenroth); Libation vase (Kean); opened shell (Paulus) |

6th

|

||

| 41 | ? | FLUTE | Copper bars (Dettmer); Bones (Aartun, Ohlenroth); Flute / Aulos (Godart) |

2

|

On side A only | |

| 42 | ? | GRATER | Saw (Dettmer); Coral (aartun); Grater (godart); Scalp (Ohlenroth); Crocodile (kean) |

1

|

Side B | |

| 43 | ? | SIEVE | 27 point triangle - sieve (Godart); Pubic triangle (Ohlenroth); female shame (Aartun, Dettmer) |

1

|

Side B | |

| 44 | ? | LITTLE AX | Bull skin (Dettmer); Leaf of a water plant (aartun); small hatchet (Godart) |

1

|

page A | |

| 45 | ? | CORRUGATED BUNDLE | Water (Pernier); Water channel (Dettmer); curled bundle (Godart); Branch (Ohlenroth) |

6th

|

The computer set contains the characters in the Unicode block Diskos from Phaistos (U + 101D0 to U + 101FF).

Manufacturing

The exact method of making the disc is controversial, although the consensus is that the symbols were not carved by hand. Helmuth Theodor Bossert described the disc in a publication published in 1931 as "the oldest printing work in the world made with movable type".

The Regensburg typographer and linguist Herbert Brekle wrote in his article “The typographical principle. An attempt to clarify the terms "in the specialist journal Gutenberg-Jahrbuch :

“One of the early clear examples for the realization of the typographical principle is offered by the infamous, undeciphered disc of Phaistos (approx. -1800 to -1600). If the assumption is correct that this is a text representation, then we are actually dealing with a 'printed' text in which all the defining criteria of the typographical principle are met. The spiral sequencing of the specimens of graphematic units, the fact that they are pressed into a clay disc (blind embossing!) And not printed, only represent variants in the possible space of the technical boundary conditions of the text representation. The decisive factor is that material 'types' are instantiated several times the clay disc to prove. "

Other authors, who were primarily concerned with deciphering, casually described the disc as the “first print with movable letters”. Leon Pomerance , however, put forward the so-called matrix thesis in 1976 ; accordingly, the symbols of the disc were not imprinted with individual stamps, but with various limestone matrices.

In 1977, Reinier J. van Meerten pointed out three different ways of producing the disc. The assumption that the disc consists of only one layer of clay, as it was, among others, Louis Godart still represented in 1995, van Meerten considered very improbable. The pictograms on one side would have been crushed or damaged by the application of the soft clay on a solid surface when the second side was printed, or the second side would have to bulge out due to the lack of counter-pressure when stamping when the pane was hung up, which is what the signs of this would have Page deformed.

In 1969, for example, Ernst Grumach represented the possibility that the disc consisted of two layers of clay which were joined together after the two sides were stamped . But even here there would be difficulties in joining the still soft clay masses together before firing without damaging them. Van Meerten varied this option so that first one of the pages was burned and then served as a solid base for stamping the second page. In his opinion, however, this should have led to a color difference on both sides, since with this procedure the first of the two sides would be burned twice, which cannot be seen on disc. The option favored by van Meerten is to pre-burn a disc, on which a thin layer of fresh clay was applied on both sides for the stamping and plastered on the edge, in order to be burned in an upright or hanging position.

Reading and writing direction

The writing direction of the applied symbols, which is important for the deciphering of the Phaistos disc, divides the representatives of the attempts at deciphering into two camps, those that assume a course of the inscription from the center to the periphery and those that assume the beginning of the text at the edge of the disc. Other reading and writing directions, such as from top to bottom and vice versa or the changing of a bus trophy , are not considered, as they are excluded by the shape of the spiral arrangement of the stamp impressions. When recording the reading direction, however, it cannot be assumed that it has to be identical to the writing direction, i.e. the stamping of the two sides of the disc.

For a long time, the study by Alessandro Della Seta from 1909, which was mainly based on typographical observations, was considered the most important indication of a left-hand movement of the text from the outside into the center of the disc. The reason was the assumption that there were overlaps of stamp impressions in the character groups A12, A15, A18 and B23, from which it could be seen that the respective left character had to be stamped after the right one, because it overlaps this. After Ernst Grumach already stated in 1962 that the writing and reading directions do not necessarily have to coincide with stamped texts, Hans-Joachim Haecker was able to prove experimentally in 1986 that "it is not the order, but the strength of the stamping that determines the overlap". This devalues the key argument that the text is running to the left. Haecker came to the conclusion: "Due to the experiment described above, overlapping of the character border is not useful for determining the direction of the writing."

In contrast, Grumach's view of the possible difference in the reading direction and the direction of the stamping of the disc was based on the assumption that there was a template for the production and that the disc could have been copied according to its model. This is contradicted by the corrections found on the disc before burning the clay disc, which are unanimously regarded as such. Finally, the corrections also provide information that the creator of the text was apparently more important about its accuracy than a perfect form of the disc. If he had intended this, it would have been possible to rewrite the still unfired clay disc after the detection of text errors or to produce a completely new, perfect disc, whereby the burning of the faulty disc would then be nonsensical. The existing text corrections thus point to a practical use of the disc, in which the accuracy of the text mattered.

As far as the reading and writing direction is concerned, Torsten Timm came to the conclusion in 2005, after evaluating arguments and counter-arguments, that the reading direction must be assumed to be left-handed. His view is based on the evaluation of the corrections, the position of certain signs, the obvious placement of some field separators and the space-saving placement of associated signs in the middle of the discotheque. A separation of reading and writing directions is not evident to him, but cannot be ruled out. However, he does not see any reasoning for this separation.

Attempts to decipher

The fascination of the discos puzzle led to countless efforts to uncover its secret. However, a script cannot possibly be deciphered by chance by trial and error. For example, if at least sixty different syllable values were assumed in accordance with Linear B , there would already be over 10 69 different possible assignments of syllable values to the 45 disc symbols.

Most attempts to decipher the disc are based on a syllabic script . This is justified by the fact that alphabet fonts have between 20 and 40 different characters, the limited text of the discus alone 45, and logographic fonts over 100, as they reproduce entire words or their designations. The frequent repetitions of certain symbols speak against logographic writing on the disc.

Successful attempts at deciphering in the past were always characterized by the fact that it was possible to find a unique assignment rule for the individual syllable values , for example with the help of a bilingual . The interpretations suggested so far for the discos either do not discuss the solution steps used or resort to methods that ultimately result in trying out syllables. None of these interpretations therefore found scientific recognition.

The following attempts to decipher (sorted by date) have been made:

- Florence Stawell, 1911 (interpretation as Greek inscription, syllabary)

- Albert Cuny, 1914 (interpretation as ancient Egyptian inscription, ideographic-syllabic mixed script)

- Gunther Ipsen , 1929 (Aegean origin, syllabary, Mesopotamian influence)

- Ernst Sittig , 1955 (interpretation as pictographic syllabary with acrophonically used symbols based on the Greek language)

- Cyrus H. Gordon , 1966 (interpretation as a Semitic text document, syllabary)

- Paolo Ballotta, 1974 (interpretation as ideographic writing)

- Jean Faucounau, 1975 (proto-ionic text about a Greek king, interpretation as Greek inscription, syllabary)

- Leon Pomerance, 1976 (interpretation as an astronomical document)

- Vladimir Georgiev, 1976 (interpretation as Hittite inscription, syllabary)

- Peter Aleff, 1982 (interpretation as an ancient game)

- Steven R. Fischer, 1988 (interpretation as Greek inscription, syllabary)

- Otto Dettmer, 1988 (Talaio's message to the Cretans, interpretation as Greek inscription, syllabary)

- Ole Hagen, 1988 (interpretation as calendar)

- Jan Best, Fred Woudhuizen , 1988 (interpretation as a local variant of the Luwian hieroglyphic writing around 1350 BC to determine property rights at the place Rhytion near Pyrgos in the Messara )

- Harald Haarmann , 1990 (interpretation as ideographic inscription)

- Kjell Aartun, 1992 (documentation of a sexual ritual, interpretation as Semitic inscription, syllabary)

- Derk Ohlenroth, 1996 (interpretation as Greek dialect, alphabet script)

- Bernd Schomburg 1997 (interpretation as calendar, schematically arranged ideograms)

- Sergei V. Rjabchikov 1998 (interpretation as Slavic dialect, syllabary)

- Friedhelm Will, 2000 (interpretation as a document from Atlantis )

- Kevin & Keith Massey, 2003 (interpretation as Greek dialect, syllabary)

- Christoph Henke, 2003 (interpretation as hierarchy of signs)

- Torsten Timm, 2005 (attempted reading assuming a Cretan script)

- Marco Corsini, 2008 (interpretation as a Greek text document)

- Iurii Mosenkis, 2010 (interpretation as a star compass)

- Gia Kvashilava, 2010 (interpretation as a prayer song to the goddess Nana, written in the ancient Colchian language, Colchis → east coast of the Black Sea)

- Hermann Wenzel, 2010 (interpretation as a planetarium )

- Gareth Alun Owens & John Coleman, 2014 (interpretation as religious text - a hymn to the great mother Ique , the Minoan snake goddess - in Minoan language ).

- Andreas Fuls, 2019 (interpretation as text in Luwian language, written with Cretan hieroglyphs, which are an early form of Luwian hieroglyphs - a letter about the occupation of a throne)

The main problem with deciphering is the small text size of only 241 characters. As a result of the uniqueness of the find, there are also no clues that could provide information about the language or text content. In the early 1990s Günter Neumann from the University of Würzburg listed the following reasons why there was currently no prospect of deciphering the Phaistos disc: “The disc is the only and unique monument that bears such characters; the text is too short to allow statistical observation; neither the circumstances of the find nor the written material itself allow valid conclusions to be drawn about the content of the text; the disc dates from such an early period that no comparisons with previous ones are possible. " John Chadwick of Cambridge University declared in 1990 accordingly:" I myself, along with all serious scholars, consider the disc indecipherable as long as it remains an isolated monument. "

Reception in fiction

- In the novel The Discovery of Heaven by Harry Mulisch the Phaistos Disc is a recurring theme: One of the possible interpretations offered is ironic "This inscription can not be deciphered."

- The novel The Feast of the stones or the Wunderkammer of the eccentricities of Franzobel begins and ends with the presentation of the discos.

- In the novel Since the Gods are at a loss by Kerstin Jentzsch , the disc plays an essential role in several plot fragments, especially in chapters 9 and 13. It is interpreted as a guide to a ritual female mass initiation.

See also

- Cretan hieroglyphs

- Linear font A

- Aegean writing systems

- Vinča sign

- Letterpress and printing technology

- Ax of Arkalochori

literature

- Luigi Pernier: Un singular monumento della scrittura pittografica cretese . In: Rendiconti della Reale Accademia dei Lincei . Series 5, No. 17 . Tipografia della Accademia, Rome August 1908, p. 642-651 ( archive.org ).

- Arthur Evans : The Phaestos Disk in its Minoan Relations . In: The Palace of Minos at Knossos . tape I . MacMillan, London 1921, pp. 647-668 ( archive.org ).

- Günter Neumann : On the state of research at the Phaistos Disc . In: Kadmos . tape 7 , no. 1 , 1968, ISSN 0022-7498 , pp. 27-44 .

- Yves Duhoux : Le disque de phaestos . Editions Peeters, Louvain 1977, ISBN 2-8017-0064-9 .

- Thomas S. Barthel: Research Perspectives for the Phaistos Disc . In: Yearbook of the State Museum for Ethnology, Munich . tape 1 , 1988, ISSN 0936-837X , p. 9-24 .

- Fred Woudhuizen : Recovering the Language and the Contents of the Text on the Phaistos Disk . In: Jan Best, Fred Woudhuizen (Ed.): Ancient Scripts from Crete and Cyprus . Brill, Leiden 1988, ISBN 90-04-08431-2 , pp. 54-97 (English, excerpt [accessed on March 29, 2018]).

- John Chadwick : The decipherment of Linear B . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, ISBN 0-521-39830-4 .

- Louis Godart: The Phaestos Disc - The riddle of a script of the Aegean . Itanos Publications, Iraklion 1995, ISBN 960-7549-01-5 (The Phaistos Disc - The Enigma of an Aegean Script).

- Derk Ohlenroth : The Abaton of Lycean Zeus and the grove of Elaia: on the disc of Phaistos and on the early Greek writing culture . Tübingen 1996, ISBN 3-484-80008-9 ( books.google.de - reading sample).

- Jean Faucounau: Le déchiffrement du disque de Phaistos. Preuves et conséquences . L'Harmattan et al. a., Paris 1999, ISBN 2-7384-7703-8 .

- Yves Duhoux: How Not to Decipher the Phaistos Disc. A Review . In: American Journal of Archeology . tape 104 (2000) , no. 3 , ISSN 0002-9114 , p. 597-600 .

- Christoph Henke: The discovery of the hierarchy of signs on the Phaistos disc . In: Göttingen Forum for Classical Studies . tape 7 , 2004, ISSN 1437-9082 , p. 203–212 ( [1] [PDF; 1,2 MB ; accessed on February 17, 2012]).

- Torsten Timm: The Phaistos Disc - Notes on Interpretation and Text Structure . In: Indo-European Research . tape 109 , 2004, ISSN 0019-7262 , p. 204–231 ( kereti.de [PDF; 441 kB ; accessed on February 17, 2012]).

- Torsten Timm: The Phaistos Disc. Foreign influence or Cretan heritage? Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2005, ISBN 3-8334-2451-6 .

- Thomas Balistier: The Phaistos Disc. To the story of a riddle & the attempts to solve it (= Sedones 1 ). 3. Edition. Dr. Thomas Balistier, Mähringen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9806168-1-2 .

- Max Paulus: The Phaistos Disc. An Approach to its Decryption - The Phaistos Disk. An Approach to its Decryption . 2nd revised edition, German / English. Publishing house Dr. Kovač, 2017, ISBN 978-3-8300-9625-2 , ISSN 1435-7445 .

- Thomas Berres: The Phaistos Disc. Basics of its decipherment . Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2017, ISBN 978-3-465-03977-8 ( reading sample [PDF; 4.5 MB ; accessed on April 26, 2018]).

- Fuls, Andreas: Deciphering the Phaistos Disk and other Cretan Hieroglyphic Inscriptions - Epigraphic and Linguistic Analysis of a Minoan Enigma, Hamburg: tredition 2019 (Hardcover ISBN 978-3-7482-5972-5 , Paperback ISBN 978-3-7482-5919- 0 ).

Web links

- Karl Sornig: Cheerful remarks on dealing with a text that is still illegible. (PDF; 668.58 kB) In: Grazer Linguistische Studien 48 (autumn 1997). uni-graz.at, 1997 .

- Torsten Timm: The Phaistos Disc. Foreign influence or Cretan heritage? kereti.de, September 2008 .

- Matthias Schulz: The strange disc. spiegel.de, April 29, 2008 .

- Jean Faucounau: The Production of the Phaistos Disk II. Remarks and Reply. anistor.gr, December 20, 2007 (English).

- Information about the Efforts to Decipher the Phaistos Disk. (No longer available online.) Users.otenet.gr, January 31, 2010 formerly in the original . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- Jerome M. Eisenberg: The Phaistos Disk: A one hundred-year-old hoax? (PDF) utexas.edu, archived from the original on August 17, 2014 (English).

- Gareth Alun Owens : TEI of Crete - Daidalika. (Website of a specialist on Minoan Crete and the Phaistos Disc)

- Gareth Alun Owens: The Phaistos Disk and Related Inscriptions.

- Hans Glarner: Schriftarchaeologie.ch (Sumerian archetypes of the cuneiform script on the Phaistos disc)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Herbert E. Brekle : The typographical principle. Attempt to clarify the terms. In: Gutenberg yearbook . Volume 72, 1997, pp. 58-63 (60f.) ( Epub.uni-regensburg.de PDF).

- ↑ a b Thomas Balistier: The disc of Phaistos. On the history of a riddle & the attempts to solve it (= Sedones . Volume 1 ). 3. Edition. Dr. Thomas Balistier, Mähringen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9806168-1-2 , introduction, p. 7 ( kreta-buch.de ).

- ↑ Karl Sornig: Wohlgemuthe remarks on handling a still unreadable text. (PDF; 668.58 kB) In: Grazer Linguistische Studien 48 (autumn 1997). uni-graz.at, 1997, p. 69 , accessed on April 26, 2018 .

- ^ Costis Davaras: Phaistos - Hagia Triada - Gortyn. Short illustrated archaeological guide . Hannibal Publishing House, Athens 1990, The Palace of Phaistos, p. 21 .

- ↑ Ernst Doblhofer : The decipherment of ancient scripts and languages (= Reclam paperback no. 21702 ). Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-021702-3 , VI. Chariot and cup - The decipherment of the Cretan-Mycenaean linear script B, p. 291/292 .

- ↑ a b Andonis Vasilakis: Agia Triada - Phaistos - Kommos - Matala . Mystis, Iraklio 2009, ISBN 978-960-6655-58-6 , Construction of the Tondiskos, p. 64 .

- ↑ Thomas Berres : The Phaistos Disc. Basics of its decipherment. Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2017, ISBN 978-3-465-03977-8 , p. 3 with note 21.

- ↑ a b c Thomas Balistier: The disc of Phaistos. On the history of a riddle & the attempts to solve it (= Sedones . Volume 1 ). 3. Edition. Dr. Thomas Balistier, Mähringen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9806168-1-2 , dating, p. 26–30 ( kreta-buch.de ).

- ↑ Torsten Timm: The inscription on the ax of Arkalochori. kereti.de, accessed on February 13, 2012 (2003–2005).

- ↑ Kjell Aartun: The Minoan script. Language and texts . tape 1 . Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1992, ISBN 3-447-03273-1 , preliminary investigations - dating of monuments, p. 8 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Jerome M. Eisenberg : The Phaistos Disk: A One Hundred-Year-Old Hoax? In: Marie Earle (ed.): Minerva. International Review of Ancient Art & Archeology . tape 19 , no. 4 , 2008, ISSN 0957-7718 , p. 9–24 (English, online [PDF; 3.0 MB ]).

- ↑ Jerome M. Eisenberg: The Phaistos Disk: A 100-Year-Old Hoax? Addenda, Corrigenda, and Comments. In: Minerva. International Review of Ancient Art & Archeology. Volume 19, number 5, 2008, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Snake Goddesses, Fake Goddesses. How forgers on Crete met the demand for Minoan antiquities. Archeology (A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America) Volume 54 Number 1, January / February 2001

- ↑ Tim Heilbronner , Heinz Scheiffele : The "Diskos of Phaistos" and the plaster bowl in the historical goods archive of WMF. A new reference to the artist-restorers father son Emile Gilliéron. In: Preservation of monuments in Baden-Württemberg. News bulletin of the Landesdenkmalpflege, 2 (2017), pp. 147-150 ( online ).

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Mysteries Of The Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, And The Forging Of History Paperback. on-line

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Snake Goddesses, Fake Goddesses. How forgers on Crete met the demand for Minoan antiquities. Archeology (A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America) Volume 54 Number 1, January / February 2001

- ↑ Kenneth DS Lapatin: Mysteries Of The Snake Goddess: Art, Desire, And The Forging Of History Paperback. Da Capo Press, 2003, ISBN 0-30681-328-9

- ↑ Pavol Hnila : . Notes on the authenticity of the Phaistos Disk In: Anodos. Studies of the Ancient World. Volume 9, 2009, pp. 59-66 ( online ); to the seal impression: Ingo Pini : Corpus of the Minoan and Mycenaean seals . Volume 2.5: The Seal Imprints of Phaestos, Heraklion, Archaeological Museum. Mann, Berlin 1970, p. 208 No. 246 ( PDF ).

- ↑ Pavol Hnila: . Notes on the authenticity of the Phaistos Disk In: Anodos. Studies of the Ancient World. Volume 9, 2009, pp. 59-66, here p. 64 f.

- ↑ Thomas Balistier: The disc of Phaistos. On the history of a riddle & the attempts to solve it (= Sedones . Volume 1 ). 3. Edition. Dr. Thomas Balistier, Mähringen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9806168-1-2 , The Diskos - Measure and Material, p. 37/38 ( kreta-buch.de ).

- ↑ Karl Sornig: Wohlgemuthe remarks on handling a still unreadable text. (PDF; 668.58 kB) In: Grazer Linguistische Studien 48 (autumn 1997). uni-graz.at, 1997, p. 71 , accessed on April 26, 2018 .

- ^ Benjamin Schwartz: The Phaistos Disk . In: Journal of Near Eastern Studies . tape 18 , no. 2 , 1959, p. 107 .

- ^ Reinier J. van Meerten: On the start of printing of the Phaistos Disk . In: SMIL. Journal of Linguistic Calculus . Språkförlaget scriptor., Stockholm 1977, p. 29-36 .

- ↑ Thomas Balistier: The disc of Phaistos. On the history of a riddle & the attempts to solve it (= Sedones . Volume 1 ). 3. Edition. Dr. Thomas Balistier, Mähringen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9806168-1-2 , The Diskos - Of Clay Layers and "Pancakes", p. 43/44 ( kreta-buch.de ).

- ↑ Thomas Balistier: The disc of Phaistos. On the history of a riddle & the attempts to solve it (= Sedones . Volume 1 ). 3. Edition. Dr. Thomas Balistier, Mähringen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9806168-1-2 , reading and writing direction, p. 88/89 ( kreta-buch.de ).

- ↑ a b Thomas Balistier: The disc of Phaistos. On the history of a riddle & the attempts to solve it (= Sedones . Volume 1 ). 3. Edition. Dr. Thomas Balistier, Mähringen 2008, ISBN 978-3-9806168-1-2 , reading and writing direction - history of controversy, p. 90-92 ( kreta-buch.de ).

- ↑ Torsten Timm: The Phaistos Disc. Foreign influence or Cretan heritage? Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2005, ISBN 3-8334-2451-6 , The dispute about the direction of reading, p. 41 .

- ↑ Information about the Efforts to Decipher the Phaistos Disk. (No longer available online.) Users.otenet.gr, January 31, 2010, archived from the original on February 4, 2012 ; accessed on February 14, 2012 (English).

- ↑ Gunther Ipsen: Der Diskus von Phaistos, Indo-European Research, Volume 47, 1929, pp. 1-41, first page

- ↑ Hans Pars: But Crete was divine. The experience of the excavations (= The modern non-fiction book . Volume 35 ). 3. Edition. Walter-Verlag, Olten and Freiburg im Breisgau 1965, p. 366/367 .

- ^ H. Peter Aleff: The Board Game on the Phaistos Disk. Recoveredscience.com, January 1, 2012, accessed on February 14, 2012 (English).

- ↑ . The unfolding of the Phaistos Disk (. No longer available online) web.gvdnet.dk February 11, 2012, filed by the original on June 6, 2010 ; accessed on February 14, 2012 (English). Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Jan Best, Fred Woudhuizen (Ed.): Ancient Scripts from Crete and Cyprus . Brill, Leiden 1988, ISBN 978-90-04-08431-5 (English, excerpt [accessed April 26, 2018]).

- ↑ The Phaistos Disk Cracked? (No longer available online.) Keithmassey.com, December 23, 2011, archived from the original on March 5, 2012 ; accessed on February 14, 2012 (English).

- ↑ Torsten Timm: The Phaistos Disc. Foreign influence or Cretan heritage? kereti.de, September 2008, accessed on February 14, 2012 .

- ↑ Marco Guido Corsini: L'Apoteosi di Radamanto. Ad un secolo dalla scoperta del Disco di Festo. digilander.libero.it, July 20, 2008, accessed February 14, 2012 (Italian).

- ↑ Page on Gia Kvashilava with links to works on the topic. In: academia.edu. Retrieved July 19, 2013 .

- ↑ Hermann Wenzel: Decipherment of the disc of Phaistos. (PDF; 3942 kB) lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de, accessed on April 26, 2018 .

- ↑ Andreas Fuls: Deciphering the Phaistos Disk and other Cretan Hieroglyphic Inscriptions - Epigraphic and Linguistic Analysis of a Minoan Enigma. tredition: Hamburg 2019. Accessed June 30, 2019 (German, English).

- ↑ Ernst Doblhofer: The decipherment of ancient scripts and languages (= Reclam paperback no. 21702 ). Philipp Reclam jun., Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-15-021702-3 , VI. Chariot and cup - The decipherment of the Cretan-Mycenaean linear script B, p. 294/295 .

- ↑ Andreas Fuls: Reading sample. Retrieved June 30, 2019 .